An update on ‘Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, Tues. 18th April. 3.45 p.m.

This is an update of relevant text in past blog: Visiting London: A Preview of the Highlights on my visit with Justin from Monday 17th – Wednesday 19th April 2023! Available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/18/visiting-london-a-preview-of-the-highlights-on-my-visit-with-justin-from-monday-17th-wednesday-19th-april-2023/

Justin took this picture on our approach to the Victoria and Albert Museum

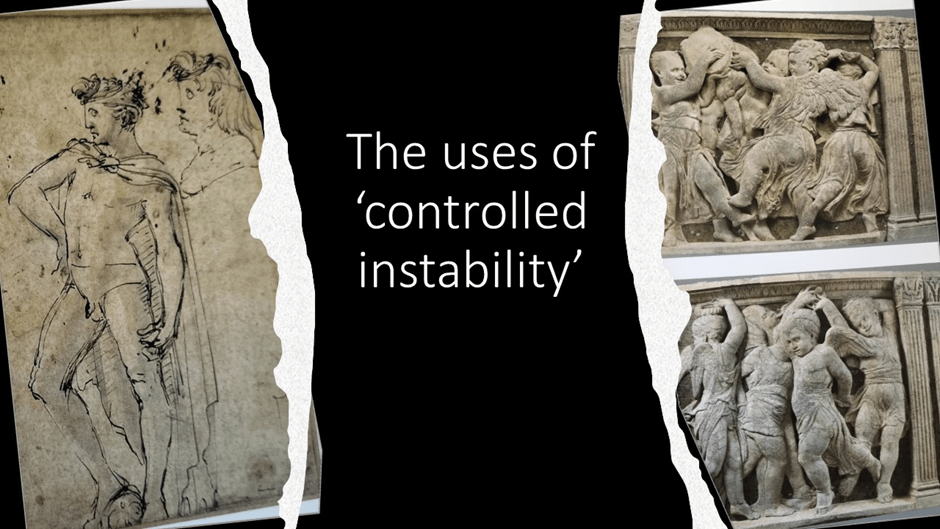

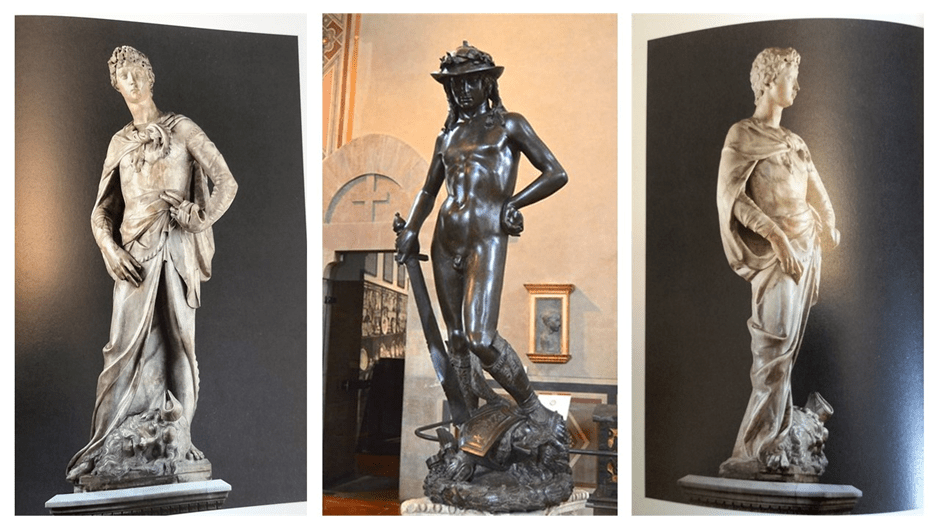

In my preview blog I struggled to know what to expect from this show and settled for a statement of the themes which would be used to sequence the curation of exhibits starting with a critical-historical focus on the origins of sculpture in the goldsmith’s craft (for as we are told there is no word Donatello could use for ‘art’ that didn’t also mean ‘craft’) to the making of art that intended to carry meanings to its ending crescendo on representing human emotion in art as analogous to the meaning of beauty to the English. What Justin and I found was a brilliantly curated set of spaces which often reflected on each. For instance, we approached and entered the room space dedicated to nineteenth-century reproductions of Donatello to see most famous of his Davids, a young boy in a pose specific to Donatello’s spiritelli named by Marc Bormand (in a catalogue essay to this exhibition) ‘poses based on controlled instability’.[1]

Illustrations from the catalogue (Petta Motture (ed 2023.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From pages 125 & 135 respectively

Yet through a window in this room space, created by faux walls is a window which frames Donatello’s earlier 1408-9 David, enabling comparison in terms of development, and the full range of his aesthetic and iconographic repertoire: from the classical-military-Biblical to the classical-pagan-amoral erotic idealism of a boy model.

The late David in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (centre) and 2 aspects of the early David (c. 1408-9) from Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From pages 107 & 106, respectively.

Attis Amorino, another ‘naughty boy’ but one with his trousers slipping down and with gilded poppy pods promising rich psychedelic visions displayed on his belt was the highlight of the pagan amoral aesthetic for us as well as the critics I had read.

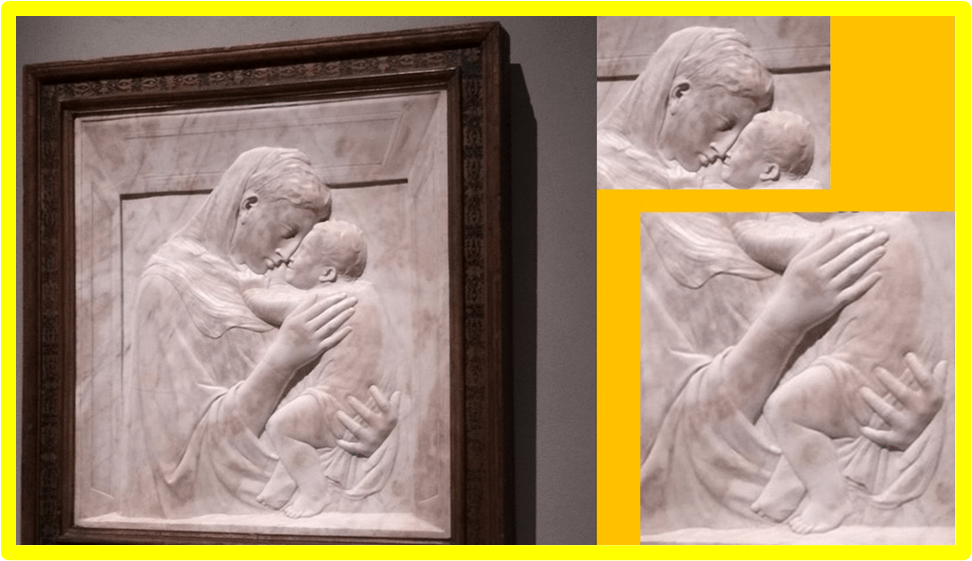

As for theme of ‘modelling devotion through emotion’ on which I expressed reticence in my preview blog, there is little I can add here – for my sense of the design of The Pazzi Madonna in this preview says much of what was confirmed in seeing this wondrous work in the flesh, at least with regard to its appearance as a design on the flat medium of a photograph. Three dimensional appreciation only confirmed the blend of illusion of solid volume and near concrete versions thereof in lighter relief. In the preview I said that it ‘contained’:

… a most beautiful inbuilding of emotional depth into a piece of semi-theatrical artifice. The inset frame appears to mime physical depth whilst being little more than a way of insisting on the artifice which has made the divine flesh. It is stuffed full of visual uncertainty, for the torso cannot be imagined in the same space as the child, who actually stands on the stage of the internal frame structure. It recalls that art still had roots in the ‘para-liturgical theatre’ (as named by Timothy Verdon) of the late medieval church.[2] This torso comes from a different genre to the child – not a view that would have passed muster in the Counter Reformation.

My photograph of The Pazzi Madonna (1420-5) by Donatello and details of the same.

What Justin and I saw here was ritually enacted emotion indeed – staged and open illusion where real physical contact and distance is carved in the stone. It is in that defined sulcus between the faces of mother and child where illusory narrow depth mime emotion and the solid dependence of the Christ child’s belief in the framework in which it is conceive and the dynamic flow of the Virgin’s beautiful hands upon her child . If you can’t see this show buy the book. Both are deeply beautiful.

All love

Steve

[1] Marc Bormand (2023: 67) ‘Donatello: Past to Present’ in Petta Motture (ed.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing, pp. 61 – 73.

[2] Timothy Verdon (2023: 52) ‘Devotion and Emotion: In the Art of Donatello’ in Petta Motture op.cit: 49 – 59.