An update on ‘David Hockney: Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’ a light show involving the artist’s own collaborative input at Lightroom in Kings Cross (the launch show for this venue). Thurs. 18th April. 11.30 a.m.

Updates part of a blog to be found at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/18/visiting-london-a-preview-of-the-highlights-on-my-visit-with-justin-from-monday-17th-wednesday-19th-april-2023/

LIGHTROOM is a new venture. A beautiful building celebrating all of the structural elegance that a supposedly brutal concrete modernism can achieve is at home in the broad sweep of concourse and elevated platforms, stairways and boulevards lined with lovely eateries, coffee bars and a series of shops replete with high end consumerist plentifulness where taste is channelled into commodities and on sale for a high price. of the new world that has arisen behind Kings Cross. My bestie Justin Curley saw in this new world, stranger to me than even the darkness of the old Kings Cross, beauty that communicated for I was persuaded to see it too.

And there is good cause to be persuaded for there is much in the resistance to modern art and architecture and the reproducible nature of some kinds of modern form in order to set off what is truly an original recreation of, and with the past that needs recuing from the snobbish voices of some aspects of what passes for cultural commentary and had done so ever since the present King Charles III, then a Younger Prince piped up about ‘monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much loved and elegant friend’. Much of art historical commentary and art criticism is of a kinship with this pointing to ‘carbuncles. These views arise from unreflective prejudice for the status quo and are oft not only elitist but inarticulately so – the frothing of an art critic like Jonathan Jones or the more elegant suave but equally dismissive tones of the art history academic.

And we have to readjust our values if we are not to fall into the Jones type. Here is on the Lightroom’s first show created on and by Hockney in collaboration with others, where talent derived from film, theatre, and storytelling (and even popular teaching) genres and modes of discourse and display are mixed to incredible effect. Let’s hear Jones, as he elaborates on his one-trick of an idea that this show is an example of modern ‘kitsch’ feeding off populist successful immersive shows on Van Gogh and Monet of the recent past:

Unfortunately, the kitsch is not just a twinkle but an overwhelming crescendo. This hour-long “immersion” in gigantic projections makes less impact than a brief glance at an actual original work of art by Hockney in a gallery. At his best he is a great painter but there is not a single real work by him here to catch your memory and hold on to your soul. Without real art, this entertainment goes the same way as all the other immersive exhibitions of art icons: into the weightless, passionless dustbin of forgetting.

Despite the slightly distasteful barbarity of the image of a work holding on to Jones’ ‘soul’ (presuming it might first be found) nothing in seeing the show, which appears to have changed somewhat from what he saw – especially that which allowed him to reduce to absurdity Hockney’s great pool pictures by making them predictive in a way that is not only tasteless but an unwitting (or possibly not and therefore cruel and unjust too) unseen predictor of the death of many beautiful young men in Los Angeles from AIDS: ‘as your eyes alight on the young men in them, including the massively enlarged naked bum in Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool, Hockney’s voiceover is banging on about how to paint water. What about the sex, Mr Hockney? What happened to that utopia?’[1] Of course, if you follow the link in the last citation you will see that Jones here thinks he is making clever reference to his already published belief that Hockney was once a vibrant radical painter of sexual utopia dulled down into a ‘bore about artistic technique: its purposes and phenomenological underpinnings.

But modern art is necessarily a meta-art, art that talks about itself and its reference to the past from which it emerges and the future to which it points. Surely this is all around one too in the new Kings Cross, for good or ill. For what has always gripped Hockney is the importance of understanding the senses in the process of both making and apprehending art requiring some kind of grasp of concepts that otherwise become empty words: surface, depth, perspectives and design, edges or boundaries and containment or otherwise.

And the LIGHTROOM show has lots of this. What Jones hears is ‘banging on’ about painting the interaction of light and water in relation to concepts of depth and surface and he yawns. But is it ‘banging on’ to say these simple words which see how the imagined is always part of any genuine perception:

Water is a surface that’s elusive in a way. All the patterns you see are just on the surface. And water in that sense is a bit like glass. You’re never quite sure what you’re looking at. …the surface of the glass or do you go through it’.[2]

Moreover, Jones is not satisfied with suggesting that old men become bores about their work-life tasks rather than be vivid about a life that Jones at least feels to be open to ‘challenging or probing voices’ or critical questions. He says:

But his theories on art are a bit dry for a lightshow. Suddenly we get a lecture on why Renaissance perspective was a dead end. If this is supposed to be accessible fun for everyone, ranting about Brunelleschi’s misunderstanding of optics is surely off target.

For the commentary is all Hockney, without any challenging or probing voices to complicate the story. He likes his work to be discussed in terms of the paradoxes of perspective, the differences between camera and human eye – and not a lot of biographical nonsense about his personal life.

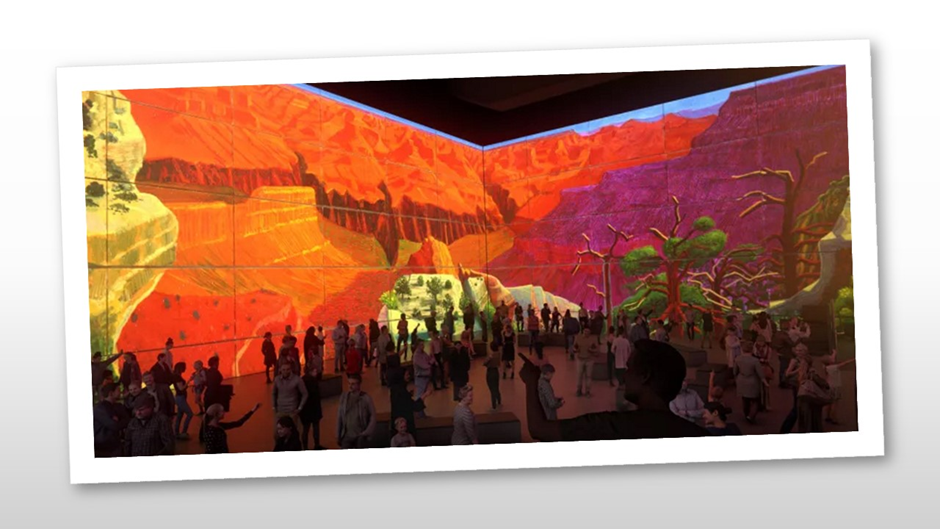

The challenge here feels too gnomic and suggestive here to be other than insulting to Hockney, and, in my view, queer pioneers of his age. And Hockney’s requirement that people see how light relate to the surfaces and relative depths of our vision in any medium – whether circumambient air or water and by showing how time varies perspective so much that nothing can be seen as entirely still and flat if seen at all is not really that dry. I did not sense that viewers found it so whose commentary we overheard. The script of Hockney’s voice-over – a collage of his voice over a number of moments in the long duration of his working life – is in the brief catalogue and is hardly characterizable as a ‘lecture’ (where did Jones go to university if his lecturers showed such intent to be understood) and never, in my view, or those I overheard, ‘dry, even ‘a bit’. After all Hockney is being purely descriptive of his artistic preparation in detailing what he learned about perspective in space and time in viewing the Grand Canyon over ‘quite a long time’ and having to ‘piece it together’. Transformed into a conventional picture based on only ONE of those photographs he said it ‘was flat like wallpaper’ and that you did not ‘see the space in it’. For if the Grand Canyon is the world’s ‘biggest hole’ and it is irregular. it’s important to realise that to look ‘into it’, you discover no ‘centre of focus’, that ‘you’re constantly looking around’, that ‘all landscape experience is ‘s spatial experience’ having time as well as physical space dimensions. Looking around in The Lightroom is not to look just at ‘gigantic projections’ as Jones thinks but to experience the time and space in the lightroom as interactive with the time of the space of the dynamic objects (even the still life and landscape ones for our eyes still saccade across and into its volumes.

And when Hockney reflects on dynamic travel in time-space – when traversing the space on a stage covered with moving figures with our eyes, or having them mobilised in a car journey in mountain roads in Santa Monica or experiencing travel through a tunnel or simply looking at a tree or treescape in Yorkshire – he must therefore reflect on what painting a picture of the world means. That is because, he says simply – controversially perhaps but not to me:

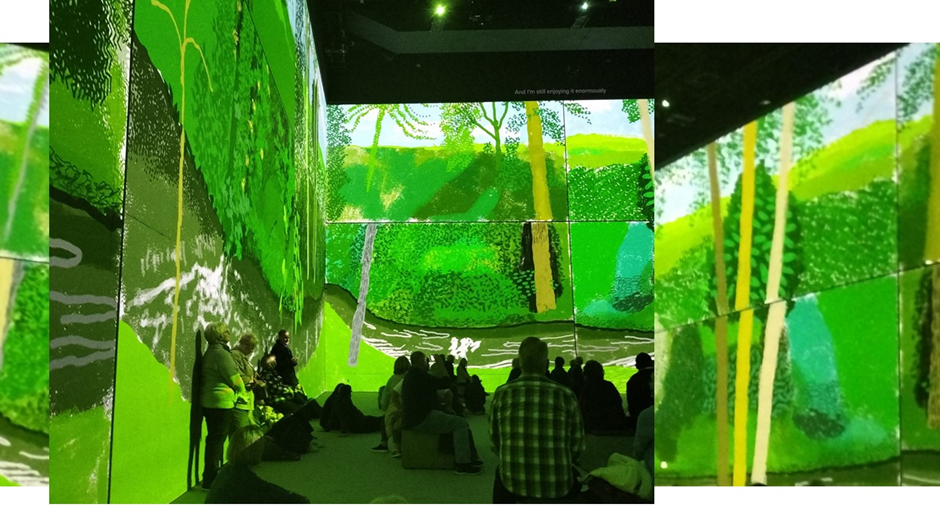

… nature doesn’t really have perspective. I’ve noticed trees don’t follow the rules of perspective. They’re so complicated, with their branches going every way, that perspective is no use for them really.

Hear that but also look around the room, where the eye invites complicity with the complexity of what we call natural ‘greens’.

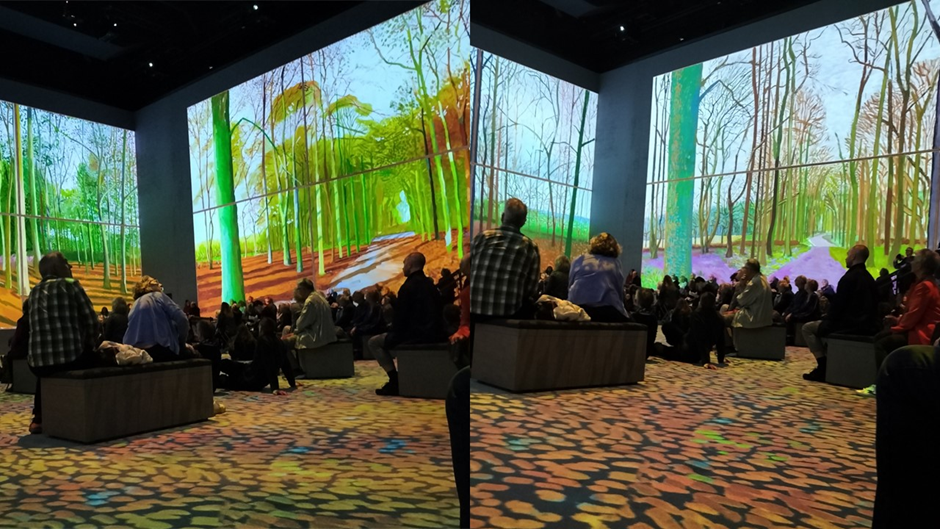

According to Jones there are no great paintings represented in this show, but the paintings of a ‘natural’ tunnel caused by trees encompassing a straight lane necessarily compare the ‘tunnel vision’ that Brunelleschi showed us was good for flat representations of architecture that obey the rules of geometry, across more than one season, make the point that we don’t see life in the same way as an architect needs to visualize three-dimensional buildings. For what contains the lane in whatever season and differently in each season, as between any other smaller or larger unit of time is something more than the vanishing point that a straight road in an imagined tunnel does. And it reduces that search for a landscape vanishing point to a simple single feature of something much more complex.

Everything, from shadows to the effects of radiance reflected in air and colour goes in too many directions to make one vanishing point as significant as conventional art wants it to be.

See this show. It finishes in October. And if you miss it, just hope the next living artist chosen for this collaboration is as good. This show hangs on Hockney’s deep appreciation in his early stage work as with the theatre and technical collaborators in this project that ‘when you move into the theatre:: ‘you have to collaborate, which means compromise’. What hope for lonely old Jonathan Jones.

All the best & love

Steve

[1] Jonathan Jones (2023) ‘David Hockney: Bigger and Closer review – an overwhelming blast of passionless kitsch’ in The Guardian [online] (Tue 21 Feb 2023 17.55 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/feb/21/david-hockney-bigger-and-closer-review-immersive-exhibition-lightroom

[2] Thomas Wade and others (ed.) (2023) David Hockney Bigger & Closer (Not Smaller & Further Away) London, Lightroom.