An update blog on seeing Good by C.P. Taylor on Thursday 20th April 2023 7.00 p.m.

A post viewing update on ‘C.P. Taylor’s Good livestreamed from London’s Harold Pinter Theatre to The Gala Theatre, Durham (and nationwide various venues) with reference to text: C.P. Taylor Good (2022, first produced by the RSC in 1981) London, New York, New Delhi & Sydney, Methuen Drama. Part of a blog that is available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/25/new-events-to-a-preview-of-the-highlights-on-my-visit-with-justin-to-london-from-monday-17th-wednesday-19th-april-2023-alice-neel-hot-off-the-griddle-at-the-barbican-19th-april-1100/

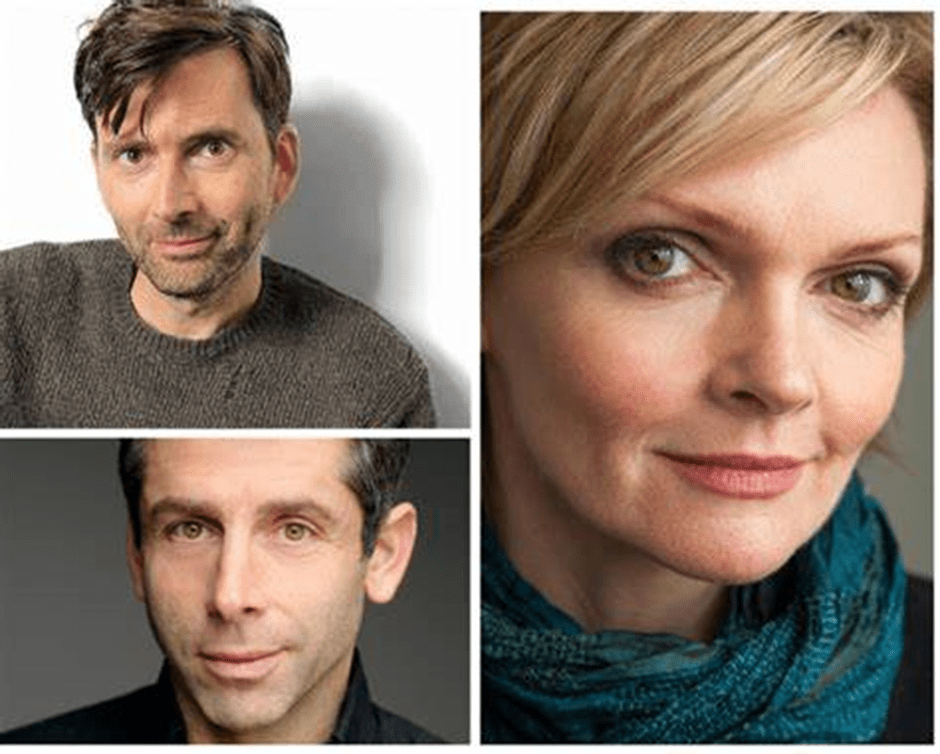

The actors

After seeing this play and contemplating how its themes came alive for me I found myself mainly attracted to what is said or can be inferred about the nature of drama from the power of an enacted performance itself. As I thought might be the case and mentioned in my preview Arifa Akbar’s review in The Guardian of 13 Oct 2022 was correct in saying that we were seeing here a present state of the production wherein the cast has been ‘reduced to only 3 of its original number of 11’. However, there is in this production a fourth cast member, a man representing the Auschwitz Camp Commandant, and a group of musicians representing a band made up of those Jews (known as kapos [the worst accusation even now that any Jew can direct at another Jew]) who volunteered for selection to play in front of the entrance of gas ovens as fellow Jews, and other people considerable expendable to Nazism, were assisted in to what had been told to them was a large communal shower room.

In this play heretofore only subjectively imagined bands could be heard in it playing to us all as if they were a projection from Halder’s mind. At its very end these subjectively imagined but projected bands are replaced by a real band enacting humane fictions, supposedly suggested by Halder’s plea for creating means for the humane extinction of human undesirables in their own, and their carers’, supposed best interests. This realisation of a politicised and supposedly ethical aesthetic moment is extremely powerful when enacted in embodied form for the first time in the play. For otherwise the play’s discourse revels in Nazi metaphysical distinctions between ‘subjective fantasy concepts like good, bad, right wrong, human, inhuman’ and ‘objective immutable laws of the universe’ as did Halder’s, and the Nazis’, false extrapolations of German thought and feeling in its great literature and art (Goethe and Wagner for instance).[1]

Embodied realities are never subjective but they do allow for varied interpretation in their actors. It is Halder’s tragedy in a sense that he finds his subconscious and unconscious life a constant intrusion into the world of ‘people and situations’ in which the body must make sense. For he: ‘can’t lose myself in people or situations. Everything’s acted out against this bloody musical background’, a background which at this point he only hears although we as an audience share the world of deep sound it provides. As Halder explains further: ‘Could it be some sub-conscious comment on my loose grip of reality? The whole of my life is a performance?’[2] What we have here, and obvious as we watch is a comment too on the grip of reality of the ordinary theatregoer, or art lover – the preference for a purely internal grasp of the consequences of acting in the world, where acting impinges on real people and real situations – such as the lives of German Jews.

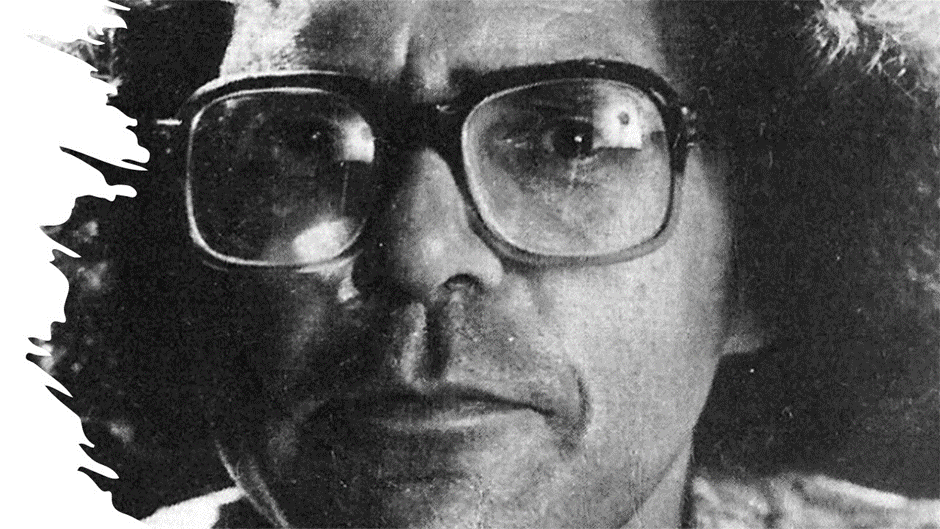

As I said in my preview: ‘I had not heard of C.P. Taylor before booking for this live-streaming and hence I prepared by reading the play and reviews with a fresh eye and with few expectations’. What I had not expected was a short interval film about the life of Taylor, who was a much more prolific dramatist than I expected (18 plays before he died young), a non-religious Jew constantly (in his wife’s witness) attempting to come to terms with the Holocaust or Shoah, and a socialist committed to seeing socialist action in determinedly non-idealistic or purely abstract terms or values. The latter had to backgrounded in real ‘people and situations’ not just principles and projected action whose consequences on those real people and situations are unknown and subject to purely mental assumptions. Halder seems in some ways like Heidegger, a brilliant man who thinks his mental constructions are as real and valid as the world in which they play out in tragedy.[3]

C.P. Taylor

In this play the majority of the roles are divided between Elliot Levey and Sharon Small. It is Small, who is the revelation though all the actors are never less than brilliant. She plays three women all influential on Halder’s philosophy of care (again similar to Heidegger’s major concern): his mother, his wife, and his student-lover for whom he leaves his wife. In one scene she must switch from the mother, dementing and frightened and sitting upstairs in a house and rooms she cannot recognise, unsure whether her urgent needs are to go downstairs to others or for the toilet and opting usually for the latter, and his wife, Helen, whose neurosis makes her a failure as a woman (in the standards of 1930s Germany) who ought to be acting to maintain family and home and is locked in abstraction. Both women are lost and play on Halder’s mind differently but with the same sense of being (to him) a burden of which he wants rid. At this very moment Halder is saying he will leave to live with his new young lover:

Helen:

… My whole life really …It’s round you … That’s the basis of my whole life …

….

Don’t just say things to pacify me, John … will you not, love? … I couldn’t stand that …

Mother:

John … John …

Halder:

Oh, Jesus … I cannot cope with that bloody woman just now …

Mother:

John …

Halder:

I’m coming …

Mother

I thought you were in the toilet.

Helen:

What are you going to do with her … if you have any ideas, tell me …

Halder:

(going) I’m coming.

Helen:

I don’t understand you, John. What do you mean … you’re not leaving me …?

Halder:

I don’t know …

(To himself) What do I mean?[4]

Here a man attempts to simplify real ‘people and situations’ by proposing ideals of distancing and escape (sometimes into himself) that he nevertheless feels unable to implement. Both women have become co-dependent on John Halder’s flight from real life and situations and both are victims of this co-dependence, unable to make any move that is not facilitated by the man in question. Each is as inconvenient to him in the form of the contradictory emotions they evoke as are the disabled, mentally ill and the ‘inferior races’ evoked by Nazi social and healthcare policy (‘Is this human life?’ says the Nazi Doctor).[5] Helen Small amazes because she handled quick transitions so that one felt both the complexity and ambiguity of feeling overwhelmed, as John as a ‘carer’ in both situations is, whilst living in the real body of induced or over-learned dependence, over-learned from John’s own passivity to real life ‘people and situations’. The actors therefore enact how actions and acting sometimes play across the cusp of physical consequences embodied in people and situations and imagined escape from embodied consequences in purely abstract ratiocination. Nowhere is this as pronounced as in the need human beings have to know they are ’good’, and hence this word reverberates in the play. Am I good at a role which requires action or merely competent enough to function (or ACT) as if I am good at it? Am I genuinely a good person or am I not or do I merely enact goodness? Is what I do ‘good’ for someone else but genuinely harmful while professing goodness of intention?

Those are the questions the play asks. For instance Anne’s student lover, Anne, once she now lives with John Halder, wife Helen and Mother safely left to their own devices says: ‘Whatever happens … round us … However we get pushed … I know we’re good people … both of us’.[6] Even Fascists need to feel they are good in every which variation of the word and this raises the ethical human problems of this play in a genuinely ethical and fine playwright. Eichmann says to Halder that his ‘paper on the reactionary, individual centered emphasis of the Jewish influence on Western literature’ is: ‘Very good, true, deep comment … first class’.[7] Such an idea becomes a fact by such exchanges in the mind of theorists of Fascism and forms a long lecture given by Halder to the audience, as if to students. It’s ‘not so good, the Jews being so low down on the anxiety scale’, he says when he makes a hierarchy of his worries: not so good but, after all, good enough relatively he thinks that it will have to do. Of his Jewish friend and psychoanalyst Maurice he says, for instance, (‘to himself’ we are told): ‘He’s a nice man. I love him. But I cannot get involved with his problems’.[8]

I have spoken more about this in my preview blog so will leave that topic here.

I wanted to watch this play very much but it as I predicted it wasn’t an easy watch. But if the term ‘good play’ means anything, this is one such.

All the best & love

Steve

[1] Taylor op.cit.: 102

[2] Ibid: 19

[3] For my thoughts on Heidegger, see this blog on a totally unrelated artwork, John Banville’s’ latest crime novel, The Lock Up: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/04/08/the-leaves-of-the-plane-trees-were-turning-and-made-faint-dry-rustling-sounds-when-a-breeze-passed-through-them-strafford-found-himself-longing-for-the-dense-drooping-heaviness-of-summer-f/

[4] Ibid: 70f.

[5] Ibid: 73

[6] Ibid: 105

[7] Ibid: 87

[8] Ibid: 21

One thought on “An update blog on seeing ‘Good’ by C.P. Taylor on Thursday 20th April 2023 7.00 p.m.”