Alan Bennet’s play Allelujah, a fable on the institutionalisation (and misgovernance) of love, death, and the NHS, as captured on film deserves more than to be called ‘sweet but slight’.[1]: A blog on Allelujah (2022) with screenplay by Heidi Thomas and directed by Richard Eyre.

The film poster

It may be unfair to pick out Peter Bradshaw’s review in The Guardian as an example for he is, unlike some critics, apparently fond of Allelujah despite what he sees as its faults. The most telling of faults to him is that it represents a ‘minor’ play of a great contemporary comic dramatist, that, as a film with Richard Eyre in charge and a cast of stellar English character actors, remains as ‘sweet and slight’ as any other excursion under the name of ‘character drama’, particularly ‘English character drama’. But other critics treat the film with more rigorous acting out of their disappointment in it. Daniel Keane in The Evening Standard, for instance, says:

I desperately wanted ‘Allelujah’ to work. Its fundamental premise – that health workers are underpaid and undervalued – is correct. With the NHS currently in the midst of its biggest ever wave of industrial action involving nurses, paramedics, and junior doctors, this could have been a timely film. Unfortunately, it is an incoherent jumble of ideas and feelings that fails to land the message it intends.[2]

The certainty sometimes that the critics have about the intentions of a piece of drama sometimes amazes me. This is particularly so when they feel that the intention they ascribe to a work sets a criteria that must make it some sort of failure in its own terms. Bradshaw too sees the ‘message’ of the work as similar but is less troubled by the fact that it come across with some of its power lost – ‘slightly deflected or undermined’:

The ostensible purpose and meaning of the film is of course to proclaim the value of the NHS, although you might argue that this faith is slightly deflected or undermined by the big narrative reveal – inspired by well-attested real life cases.

The ‘slightly’ is less damning than to see the aim of the film as a matter of proclaiming ‘faith’ in a supposedly contested idea (the ‘value’ of the NHS) in our national and individual psychology as well as in social and economic political life. And, as with other critics, the responsibility for this undermined purpose is blamed by viewers (even the non-professional ones) who disliked or were disappointed in the film or play on its denouement – its ‘big reveal’ at the end. Perhaps the most extreme versions is in The Observer, whose critic, Wendy Ide, sees that denouement as turn to the genre of the crime thriller:

The hospital is threatened by penny-pinching government officials. The medical staff struggle on, undaunted. But what seems to be a stirring tale of a community standing up against the powers that be takes a darker turn as the story swerves unexpectedly – and rather clumsily – into thriller territory.[3]

But I think this is precisely because those critics and viewers misunderstand the film and indeed Bennet’s common reference to ethical problems in plays. Those plays are themselves neither comedy nor tragedy but, using Boas’ term for a type of play in Shakespeare he first identified, ‘problem plays’. I need to say more about this later and why it is appropriate for this film to make an excursion into what looks like a murder thriller. It is not unknown in Bennet’s earlier plays:

It is clear also however that the film does allow us to see that the NHS is at risk from the ideology of top-down management and how it does this needs spelling out first. The film picks out a real characteristic of the management of national health in Great Britain, which can be described in the following broad brush-stoke narrative. From the reforms of the Thatcher era onwards change in the NHS focused on management priorities of economies of scale and the drive to supposed excellence that was thought to derive from large, specialised units – the so-called ‘centres of excellence’ referenced in the film – which led to the closure of small and ‘cottage’ hospitals and the gradual elimination of state provision of free health care for older vulnerable patients.

Responsibility for that care passed into the social care sector and entailed potentially large means-tested costs for older people with chronic conditions. Even the place in which most deaths occurred – for decades this was in hospitals – began to shift to the social care home sector (a fact that led to the horror of government spread COVID in care homes quite recently in history). The trend to larger number of deaths occurring in care homes is continuing post 2017 it is believed in extrapolation of trends shown in National Statistics for 2004 – 2016:

Hence the central characters amongst the patients are the elder former miner, Joe Colman (played by David Bradley) and his son Colin (played by Russell Tovey). Joe dies because he prefers to stay in Bethlehem hospital (known as the ‘Beth’) rather than return to isolation in his care home, The Rowans. But he dies, perhaps, having specifically chosen the option of death – it is left in the air whether this is the case in the screenplay, having first recognised the validity of his son’s sexuality for what seems to be the first time. Colin is gay but appears unsettled in that identity, as indeed his father recognises more readily than Colin, for it is Dad who points out how formally Colin treats his partner.

Each of these two issues of both political ideology and personal identity bring their own kind of deep rifts of understanding and feeling between father and son. However, it is the implicit debate about the nature, and demonstration of love, in families – whether they be chosen or not-chosen families, that underlies them in the play. Colin, after all – until the end of the film – treats his lover, with whom he lives, with something of the same cool contempt to any claim of an emotional bond between them both as he does too his father. Love is a sticky word that will not appeal to Colin until late in the film when he begins to generalise it to notions of ‘care’, without which healthcare becomes so mechanical; or so he tells the Governmental Health sub-group of whom he is the management consultant. Indeed it was his idea to close cottage hospitals like Bethlehem and was visiting his father at the point of his story told in Allelujah in part to confirm that decision. Colin also accompanies the Minister of Health to cultural events like the opera whilst denying, to his father, that the Minister is ‘one too’. All of this suggests covert self-interest in sexual relationships in these characters, motivated largely to achieve any lever, and a close relationship might do as such a lever, that increases their personal power. Thus a speech about the need to recognise ‘love’ as the basis of care given at the ‘Beth’ which he reports to the sub-group (to its vast surprise and chagrin) starts his political and personal alienation from his government role and his journey back to bonds of demonstrative love in his own life.

And these journeys back to love are occasioned ONLY when he comes to accept that human life and human bodies are vulnerable things, even to the passage of time, through enforced greater proximity to his father’s ailing body. It is a shock that impacts even more on Joe who is shocked to a death-wish on his first experience of involuntary urinary incontinence at the ‘Beth’. There is then more than a sentimental storyline in these stories about the recognition of the power of love in familial and couple care because the subject of this film is only tangentially the NHS per se. This is because, for the generations of persons alive currently, the NHS became the main vehicle of dealing with older age and, indeed, with death as a substitute for family care. The film does not therefore, in a ‘sweet but slight’ way, set out to honour the NHS but to put that great institution into the context of the care of elders. This is why the film closes with the crisis in care of the COVID pandemic and government misgovernance of that epidemic particularly in relation to elders, which became the pronounced theme of government plans for the NHS – the theme of shifting vulnerable elder care, even under Labour governments, from the responsibility of Government (via the NHS) back to families or substitute social care institutions. The NHS was to be repurposed to a focus on acute not chronic care.

Of course at the same time social care, which was to the designed repository of the aged, even when extremely vulnerable, through both care and designated nursing homes. That was the context indeed of my own entry into social care for elders as an Older People’s Social Worker in the 1990s. But I have established this narrative of social change in healthcare really to return to the theme of Allelujah. The true theme of this drama is social responsibility for vulnerable elders and for death and the dying, not just the NHS as the main jewel of state responsibility to the many regardless of wealth or income.

In doing so I will have, unlike the reviews I’ve cited, to employ a narrative ‘spoiler’. For what critics call variously a ‘dark turn’ or deflection from a cosy view of the NHS, is not such because this film is a comedy (for it is as dark a type of this genre as any amongst Shakespeare’s ‘problem plays’, as I have said earlier. I have referred to this already above. The ‘big reveal’, in Bradshaw’s term, is that the down-to-earth Yorkshire nursing sister so brilliantly played by Jennifer Saunders, is revealed to be a nurse who feels it appropriate to kill her patients apparently because she cares for and loves them. Other critics of the film ignores the cases of murder in institutions by nursing and caring staff that were reported at the time covered by the film. The study in the link above makes, though a study from the USA, it clear that the murders of vulnerable elders in this film does not represent all the factors characterising these murders which the authors of the study believed to be the main ones in the USA, especially the finding that most cases involved registered male nurses, exercising power.

Results revealed personality and behavioral (sic.) indicators manifested by nurses who murdered or were accused of murdering patients, and details of murder events. Registered nurses were accused and convicted of murder most frequently; male nursing staff were disproportionately represented. Old and acutely ill patients were frequent victims and poisoning with medications, the usual murder method. Power/dominance ranked as the most frequent motive.[4]

Murder by registered nurses, though very rare, is used in this play in relation to the true underlying themes of Allelujah and how these relate to the handling of the NHS. For there is no attempt I believe in this film to smooth over the problematic issues of power over temporarily dependent people involved in the provision of healthcare. Nurse Gilpin (Jennifer Saunders) is no Daniela Poggiali.

Indeed, she has a back history of what is described in professional jargon as ‘informal care’ for her own mother at home. She has strong ideas about the shift to governmental institutions of the kind of care and love she believes ought to be given by families: ‘if they love them so much, why do they put them into the care of strangers’ she says (or something like it). In the film Gilpin has a list of people who had reached such a state of dependency on ‘care’ that they do not want, or at least appear not to want, to live on as they inevitably must in a space not their ‘own’. I say ‘appear not to want’ in the last sentence – for their facilitated death at her (or their own hands for Joe Colman is merely reminded his night drink is there for him to take at his own choice) may even have been (if not in so many words) wished for by the victims of her death-awarding ‘care’: the facilitation of both deaths in the film is in the form of milk laced with an overdose of morphine. Of course the question begged here is to whom is death ‘considered preferable’ and with what expression of consent. We know Gilpin prides herself at the absence of the smell of urinary incontinence at the Beth but her means of eradicating it, if Joe Colman’s experience is typical, seems severe, for after all a ’one-off’ episode of incontinence is not a sign of such incontinence as Joe himself says, though that saying is significantly NOT validated by Gilpin.

Nurse Gilpin, apart from her gender, does fit the characterisation of registered nurse killers described by Wolf and her colleagues above from evidence from the USA. She is significantly drawn by reference to what seem to be markers of a strong and possibly psycho-morbid character. She uses her sexual power to ‘capture’ Joe and her maternal one to bind her first ‘victim’ in the film, a lady with an advancing dementia (brilliantly played by Julia McKenzie). The main symptom of her dementia in the film is the characteristic apparent confabulation in which the destabilised memory store fails to recognize where it is currently ‘at home’. But we soon learn that this repeated phrase ‘but it is my home really’ is not entirely confabulation, but a confused memory of her daughter and son-in-law’s legal possession of her home, dependent on her living at last a few more months. Her death at the ‘kind’ hands of Gilpin frustrates that possession from accruing inheritance tax for those family beneficiaries. This entire scenario represents how elders are treated in the psychosocial and financial management of social and health care arrangements. If you take all this seriously (as all human beings will do as power over our earthly possessions passes to inheritors, and care cannot be depended upon (nor love neither)), you will see the deficit in critical summaries of the film like Bradshaw’s that says it is at base, a ‘veteran Brit character-actor lineup in a care setting’ that is enjoyed only at the level of character comedy: a ‘watchable, undemanding drama’ that ‘rolls along capably, enlivened by unmistakably Bennettian gags and drolleries which come along every minute or so’.[5]

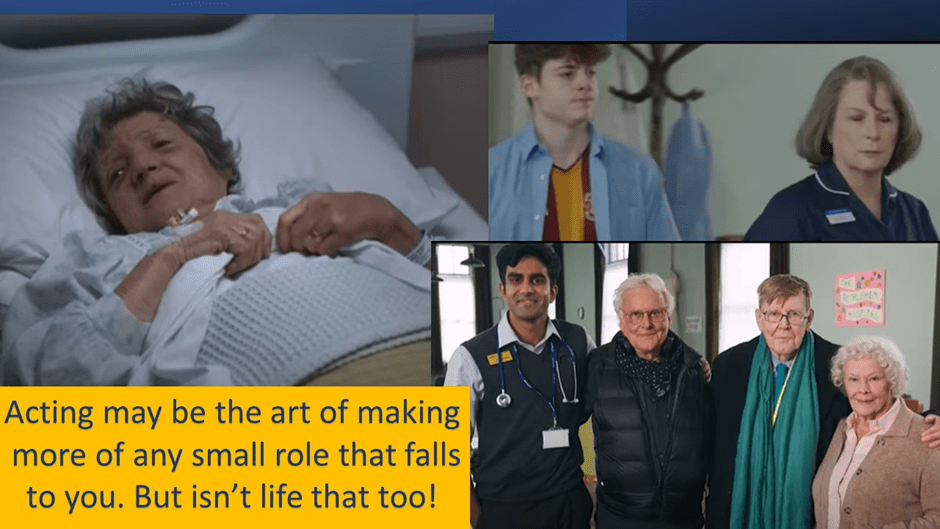

Sometimes middle-class cultural gurus can get Bennett and the Bennettian drollery wrong. I think this is because the character actors – from the principal to the minor characters – play their role as if it mattered and should matter, and be the focus of a loving regard. As I say in the collage below: ‘Acting may be the art of making more of any small role that falls to you. But isn’t life that too!’ I meant by this comment to refer to McKenzie pictured and to the hopeless teen intern, Andy (played by Louis Ashbourne Serkis) in these sentences, but even stars like Judi Dench, and surprisingly to me, Jennifer Saunders too, illustrate that great reputation does not deny the ability to achieve fine effects whatever the size of role.

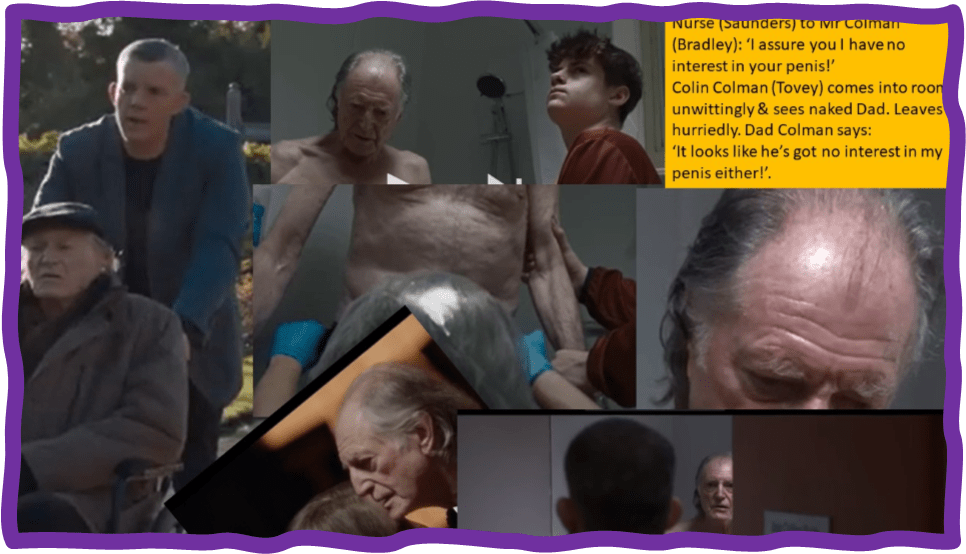

The role of Andy the intern is a problematic one for critics, even though none I read mention him. Lots of unpursued material characterises him. The critics often mention the fragmentation of the film’s purpose so examining Andy’s role in the film is useful, for I believe his purpose as a character contributes well to the whole film. Andy, for instance, is clearly a foil for Colin Colman – a picture of the limited opportunities of a boy who stays stuck in Wakefield, rather than makes a break for education and London. Colin engages with him in the hospital car park, playing on his bike, and though nothing sexual or romantic happens here despite the fact that Colin’s gay identity has become a known fact between them in various interactions between Colin and his father where he has been present, the identification achieved between them is magnetic. In one such interaction there is an example of the various versions of sexual role-play between Gilpin and Joe. In my collage below the central pictured interaction is where we see the back of Gilpin’s head at the level of Joe’s groin. Almost as a recognition of sexual meanings, Gilpin drily says to Joe that ‘she isn’t interested in his penis’. Shortly after in the scene Joe says to Gilpin (and Andy since he’s inevitably present) that Colin ‘isn’t interested in his penis either’, for Colin has quickly withdrawn from accidentally seeing his Dad naked. This example of Bennettian drollery weaves the embarrassment of Andy into that of Colin for it acknowledges the latter’s sexuality. Only Gilpin and Joe remain unembarrassed by this Bennettian jokey play. It shows, as so does much else, that our only chance of happiness is in openness to our own selves.

This sexual play is a necessity to break down stereotypes of ageing in front of audiences of younger people A fine other example is used in the trailer to the film. Interviewed by the TV documentary crew reporting on the Beth, Patrick reminisces about his role as factory foreman with ‘ten men under me’. The chance of a sexualising riposte is not lost on one lady. The establishment of a meaningful old age free of stereotypes of victimhood is thus achieved. The aim is respect and love and explains why so much of the burden of the film’s message, right into the treatment is carried by the doctor who, since his Asian-origin name is considered unpronounceable in this fictional Yorkshire, becomes known as Dr Valentine, and is truly a carrier of the message of love as the over-riding necessity of care.

The theme is born too though by Molly, played so wonderfully by Judi Dench, whose role is to be marginalised, even visually in shots like the one below, and whose interests in reading are in the marginalia of books not books themselves and, by extension, what people in that marginal zone say. Alleluja too unfolds fragmented lives and experiences at the margins of life which teach us to love each other – in the form of intern teenage young men, adorable queer occupational therapists, or librarians who prefer the responses of real people to books to books themselves. Wendy Ide may think that there is a ‘a collision of tones and conflicting messages’ such that ‘it undermines its own earnest coda in support of the NHS’, but in doing so she misunderstands that the NHS lives alone as a principle that comprehends not only its own vital central purpose but the people whose marginal lives it makes continuingly possible.

So do not be put off by mealy-mouthed reviews. Enjoy the humour of this film but find the beautiful dark heart there that shows there are no simple answers to the problem of a society aimed at eradicating care and love from its belief in making more efficient its own central aims wiping away the messy diversities within, or tidying them up as Nurse Gilpin does. The NHS is vital because it is, in itself, not an answer but a means to facilitating the answer we as a community find when we realise that care and love need various channels of expression – at the margins of life, in the localities of a nation as well as strategic central protocols.

I loved it.

Yours with love

Steve

[1] Peter Bradshaw (2022) ‘Allelujah review – sweet but slight Alan Bennett hospital drama’ in The Guardian (online) [Sat 10 Sep 2022 19.17 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/sep/10/allelujah-review-judi-dench-stars-in-sweet-but-slight-alan-bennett-hospital-drama?CMP=share_btn_tw

[2] Daniel Keane (2023) ‘Allelujah film review: a loving but unrealistic and ill-judged portrait of an NHS in crisis’ in The Evening Standard (online) [20 March 2023] Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/film/allelujah-film-review-nhs-richard-eyre-jennifer-saunders-b1067099.html

[3] Wendy Ide (2023) ‘Allelujah review – starry but jarring film of Alan Bennett’s hospital play’ in The Observer (online) [Sun 19 Mar 2023 12.30 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/mar/19/allelujah-review-alan-bennett-hospital-play-richard-eyre-judi-dench-jennifer-saunders-derek-jacobi

[4] Zane Wolf, Maureen donohue-smith, & Kerrin C. Wolf (2019) ‘Nurses Who Murder or Who Are Accused of Murder’ in The International Journal of human Caring (23 (1)) [March 2019] DOI:10.20467/1091-5710.23.1.51 Abstract available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332216125_Nurses_Who_Murder_or_Who_Are_Accused_of_Murder#:~:text=Nursing%20staff%20have%20been%20tried%20and%20convicted%20of,sources%20included%20news%20reports%2C%20books%2C%20and%20court%20records.

[5] Peter Bradshaw, op.cit.

[6] Allelujah (2022) – Full Cast & Crew – IMDb https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15765412/fullcredits/