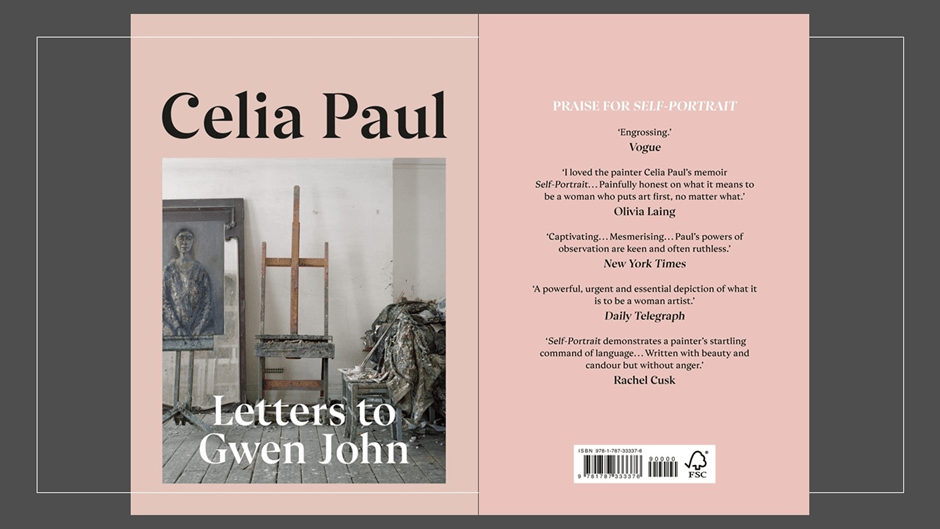

‘Since Rodin’s death, Gwen no longer needed to make an inviting space to entice a lover – this interior sounds as bare as my own’.[1] This blog examines the uninviting space into which only ‘absent presences’ may enter.[2] It is a very subjective reflection on power, sexuality and sex/gender in Celia Paul’s (2022) Letters to Gwen John London, Jonathan Cape.

There is a terrifying tendency in the cultural moment represented by the insistence that art history is an autonomous discipline with clear boundaries to other arts, including the art of living one’s life even in if realised in the senses of no-one but one’s own, that is forever wanting to reduce visual art to its own standards. Indeed some critics wear this kind of thinking as a badge of their intelligence. As a result they fail to be honest to what a book might express other than what makes it fit into some generic type of book. Although the perceptive critic in her does point to her impressions contradictory complications in the work, for Rachel Cooke, writing in The Observer, she sees it as a comparative failure next to Celia Paul’s earlier book Self-Portrait (the link is my very brief blog thereon); whilst still being satisfactorily summarised as being:

very much an artist’s book, its author at her most insightful when she is writing about her practice (the stink of turps, the right paints and paper), or describing beloved pictures in the National Gallery (Mantegna, Piero della Francesca, Robert Campin). It’s rarer than one imagines, this: so few artists are able to articulate why, and how, they work.

This is necessarily a limiting judgement and does not tell us much about the book, other than to insert it into the discipline of the history of art and artistic technique even if it ‘doesn’t quite reach’ the level of an artist’s autobiographical writing attained by Keith Vaughan’s Journals, Paul Nash’s Outline, and Celia Paul’s earlier book[3]. None of these books are of a generic type I’d suggest, other than each being extremely good writing (though less so in Nash). I think therefore that the best review I have read is one that is by a person interested mainly in the kind of writing this rather than its contribution to lives of the artist, by the novelist Carole Burns. Burns rightly admires how Celia Paul describes the art made by herself and others, as in this statement:

More than the sometimes overly intellectual art criticism in journals, or the sometimes dumbed down exhibit labels that museums provide, artists talking about another’s work is often surprisingly plain, direct. They help me see.

However, her moving piece, in the online Wales Art Review, struggles openly to describe the book because though what Celia Paul says about art are ‘the simplest, the most exquisite, and the most exciting moments of Celia Paul’s complicated book’, we cannot help but see that we need to move beyond exquisite simplicity, however directly helpful in looking at visual art, the things that represent the book’s complications. Burns constantly repeats her insistence that both she and other readers need to acknowledge and, frankly, puzzle over as she does:

the more complicated nature of this book: part memoir, part biography, part artist appreciation, part diary. As she draws parallels between her life and Gwen’s, Celia Paul turns these “letters” into an exploration of being a woman artist; of balancing art and life as a woman. As she examines the sexual relationships each woman had with a more famous male artist – Celia Paul with Lucian Freud, Gwen John with Auguste Rodin – the book takes its place alongside the Me, Too movement, examining the dynamics of power, passion and privilege wrapped up in each of these relationships.[4]

And I would go further because although the exploration of female artists and their connections to me – not just important male artists like Lucian Freud and Auguste Rodin – but other men differently related to her through extreme complications of the processes engineered by perspectives of sex/gender and power in lives generally, not just those parts that touch on creative art. Hence the book explores the ‘balances of power’ not only between heterosexual lovers (Charlotte Bronte’s The Professor (or Emily’s ‘Heathcliff’) for instance) but women and their fathers (including ‘holy fathers’ of the priestly kind for Gwen and perhaps even Celia’s visionary mother), sons, brothers (suddenly I want to know so much more about Augustus John and to finally read Michael Holroyd’s revered biography which Celia Paul acknowledges as a source), friends (sometimes queer like the intriguing and evocatively pansexual portrait of the curator Hilton Als) and male readers. There are moments that constitute a truly fascinating new kind of literary criticism in this book, when it touches on D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers for instance that seem to me as illuminating for readers of the novel as any conventional literary criticism I have ever read, and perhaps more so, in that they puzzle out the relationships between sons and mothers as ‘lovers’ more fully than anything I have read outside of reading that haunting book itself.

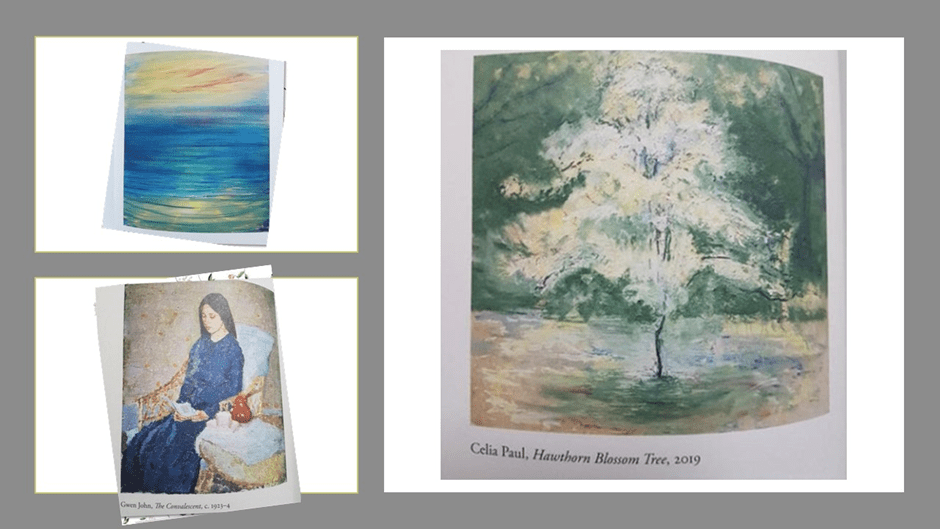

Some highlight paintings in the book

Likewise the book does not shy away from hints about how artists with very solid heterosexual credentials, like Rodin if less so with Lucian Freud’s secretive sexualities, get bathed in queer sexualities, even if only as observers and imaginers (though that is queer enough not to be heteronormative in theory at last – for I believe many straight men fantasise about their female wives, friends and lovers having lesbian sex as much, as we know from Gwen John, Rodin did). Celia Paul tells us that amongst the drawings owned by the Rodin Museum ‘a number of them are of women masturbating each other’. After a three-cornered voyeuristic sexual relationship including Hilda Flodin as well as Gwen Rodin asked Flodin ‘to lie down with (Gwen) and caress her, and for Gwen to respond’.[5] And this quality in their men, since both Freud and Rodin used their lovers as models, often simultaneously to using them sexually, aligns with the way male values confuse the value of art with its quality as something displayed, exposed to the eyes (usually of other men).

Celia Paul constantly sees the art of both women (herself and Gwen John) who are her joint subject-matter as balanced on the cusp between wanting exposure as an innovative female artist (producing art different in quality to that of men) and the desire not to be seen or heard (of) at all, even in memory. Thus Augustus continually forced exhibitions of his sister’s work, Celia tells us, inviting critics (males inevitably) to notice the presence in the New English Art Club of her ‘little pictures’ which are ‘almost painfully charged with feeling, even as their neighbours are empty of it’. Their sister Winifred ‘persuaded him not to publish’ his assessment of Gwen as ‘the greatest woman artist of her age, or, as I think, of any other’ because ‘Gwen would wish to be forgotten’.[6]

Once sensitive to the themes in this scenario, one constantly sees in this book complexly contrasting and even contradictory wishes for both presence and absence at the self-same time: and likewise for talk about oneself and silence, visible exposure and retiring seclusion or even confinement from the eyes of the world. How chilling in this context is this paragraph pointing out the similarity (nestling deep in the differences, between Rodin and Freud. Both are manipulators of the appearance of self and other (or themselves as another) as conscious of their making of themselves in artifice as any other stage director in the theatre before an imagined but thoroughly presumed public audience:

Both Rodin and Freud consciously staged their own appearance.: Rodin gazed at the camera with the dreamy, clairvoyant eyes of a mystic monk, a Rasputin, while Freud sucked in his cheeks and looked into the lens with the wide-eyed intensity of a bird of prey.[my italics] [7]

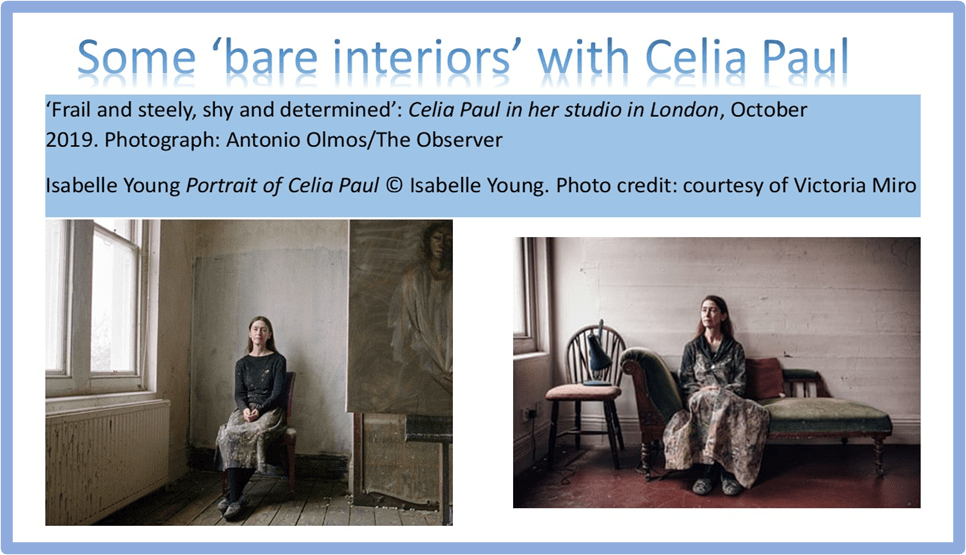

These men enjoy their exposure in the role of predators of different kinds. It is not however that Celia Paul believes this kind of self-exhibition is alien to women, for there is nothing of simple biological determinism in her capture of difference in persons who are performatively women. When bot enacting a role (as with Rodin) Gwen John could love women sexually as well as she could men. Celia writes that ‘Gwen had erotic imaginings about’ her ‘Slade friend Mary Constance Lloyd’, which she thought unrealisable when Mary posed nude for her, instructed to: “Let her draw you to her to kiss your hand. Later on you can kiss her more willingly with love & later still put your arms around her neck & kiss her, giving yourself’.[8] No male gaze has been more insistent in its visual and narrative imagination. This kind of exposing gaze prosecuted on another woman runs counter the desire for rendering the female body insensible – dark or opaque to every sense – and akin to self-imposed isolation in a cell in which even one’s own body makes no appearance, even to oneself, so bare is that stage – a ‘bare interior’. These are the interiors in which both Gwen and Celia Paul chose to live by Celia Paul’s account and to which she refers in the quotation in my title: ‘Since Rodin’s death, Gwen no longer needed to make an inviting space to entice a lover – this interior sounds as bare as my own’.[9] And, despites its clutter (obvious to all eyes but her mother’s whose vision was entirely on her inner life) the room inhabited by her mother during her last years was equally empty: ‘I have inherited her lack of regard for the material look of a room. The walls in my flat are similarly stained with damp, but my rooms are almost bare, whereas her rooms were bursting at the seams with … household detritus’.[10]

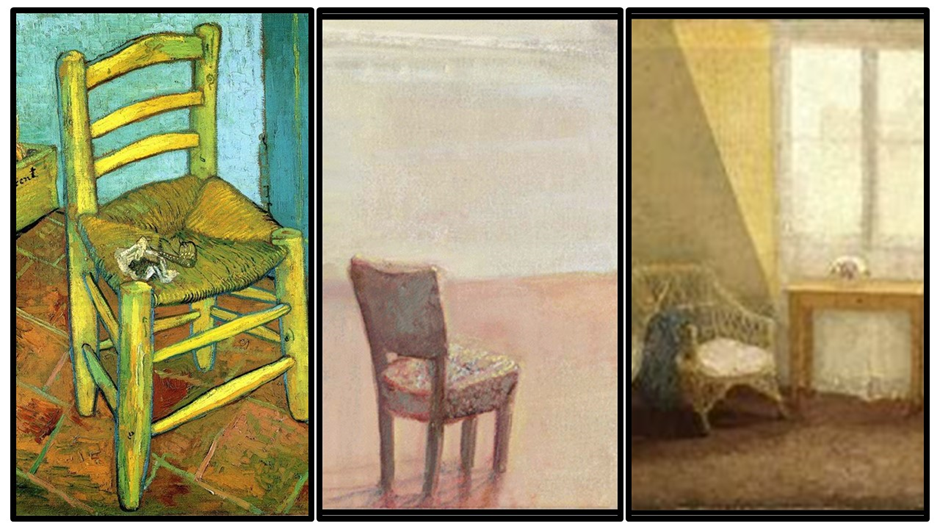

Yet again this difference, between a longing for isolation from the world and the stuff that offers ‘material’ to the outward-facing senses is not confined to women as an outcome of sex/gender difference, as even the burst critics say it is. They are correct that this is a feminist vision however, it is just that it is not a product solely of biological difference, for both Celia’s mother and Celia herself find the same trait in Van Gogh: the refusal to be exhibited to the eyes of a non-understanding world and that ‘the only way to preserve any shred of dignity is to isolate oneself’ from the material world of possessed objects, in which form art is so often found. Celia Paul hopes that this is how Gwen sees Van Gogh too and not as Walter Sickert did as someone without restraint. But of course, she reasons to herself, Gwen must have thought thus, for like Van Gogh she wished most ‘to lead a more interior life. You wrote “be alone, be remote, be away from the world, be desolate. Then you will be nearer God”’. [11]

I go to some pains to stress this spiritual ascetic in this work because it is, as it were, the test case in which it is clear that neither Celia Paul are stuck in a biologically conditioned vision of sex/gender in relation to art or the world of the emotions. The mystical and ascetic aesthetic is after all what most characterises the commonalities, in again in very different forms as conditioned by the affordances offered by history – and not just art history – to both women. It characterises for instance the empty chair paintings of both women as artists, and perhaps that of Van Gogh too. After all Van Gogh’s Chair is the model of a painter’s self-portrayal as an ‘absent presence’ which all three painters celebrate, and as which Celia Paul says forms one of many ‘absent presences’ more deeply considered than that of the personae that she jokingly refers to in the Acknowledgements made in her wonderful book.[12]

An empty chair is a truly absent presence in autobiographical or self-portrait paintings by Van Gogh, Celia Paul & Gwen John.

The relationship between ‘absent presences’ and bare interiors (rooms stripped of overly ornate and decorative presences, is a difference true between art that rejoices in its staged display on a wall or a text of the history of art and one that looks for a more private inner meaning that will differ between viewers – what I mean, I think, by a ‘mystical ascetic aesthetic’ in the latter case.

Of course this perspective, which has a complicated take on sex/gender paradigms, does not exclude feminist reading – quite the reverse. However, in our own days gender critical perspectives have reduced their kind of ‘feminism’ to a game of ‘hunting the oppressive penis, I think Rachel Cooke may show how that case becomes dangerously near (but for the phrase ‘to a degree’, to biological determinism, when she says: ‘this is a volume born of battles that are, to a degree, universal in the case of women: the cruelty of men, the shame of ambition, the struggle (always!) to find space to think, to be free’. This theme certainly shines through but with emphasis more on the agency of women to reject sexual stereotypy. Carole Burns gets the issue completely correctly in my view, in ways that show the agency of female artists in not just displaying ‘balances of power’ in heteronormative or homonormative relationships but in changing their meaning for ones in which the battle is seen as winnable:

Toward the end, Celia writes about a Renaissance painting by the female artist Sofonisba Anguissola, a tricky double-portrait, in which she depicts her more famous teacher, Bernardino Campi, ….In making her own self-portrait the more prominent, more striking, Anguissola famously “subvert(s) the expected gender power-balance,” as Celia writes.

As Burns the subtle writer goes on to demonstrate, Celia Paul performs an equal subversion with the image of Lucian Freud: in her painting Looking Back: Bella, Me, Lucian, she renders Freud passive to her; “This time Lucian is alive. I’ve captured him alive,” she writes. [13] The pictureof a man enthralled by a belle dame sans merci is beautiful, However, l would insist that playing equal power games to Freud’s depictions, which even Burns suggests to be going on here, is not I think how Celia wins her feminist case. Indeed she makes the point earlier that her subversive sexual political interests differ enormously from Lucian’s:

The way I think Lucian influenced me most was by his obsession with balances of power within the dynamics of a relationship. … I am not interested in balances of power. Or rather, I am interested in balances of power, but not of an obvious kind.[14]

In Carole Burns terms: Celia Paul’s book considers a very different problem to the simplistic one in Rachel Cooke’s formulation:

Why do her and Gwen’s biographies always end up asserting that they are each “a painter in her own right” as if they are “still bound to our overshadowed lives, like freed slaves.”

“What is it about us that keeps us tethered?” she asks Gwen. “Both of our talents are entirely separate from the men we have been attached to – we are neither of us derivative in any way. Do you think that, without fully understanding why, we are both of us culpable?”

The book is also a complicated answer to this complicated question.[15]

To understand why women collude in maintaining imbalance of power in patriarchal situations is a question deeply emotionally and intellectually challenged artists like J.K. Rowling just don’t ask, for the answer is always the same: Men made us thus! Not so Celia Paul and, according to Celia, Gwen John. Women of this ilk see power as shifting and variable even in the despite of structured socially constructed versions of it, such as is patriarchy. It is this which makes them hopeful of the possibility of true change in such balances. This book will not work for us unless we see the relationship in it between Gwen and Celia as one, that though imaginatively or artificially created, as dealing with the dead always necessitates, that changes through the progress of the book. It is vital that we see that or we will miss the fact that Celia fears domination by Gwen as much as by Lucian. Gwen John continually gave way to Rodin, even abandoning her own art for a time as Paul shows us, whilst Celia knew the need for ‘a room of my own’, and despite turbulent exchanges between them, steadfastly refused Lucian’s request to paint from the studio he bought her across from the British Museum: ‘I was alarmed that he presumed he could invade my territory. I told him I needed to keep this place for myself, for my own work, … I didn’t let have a key to my building or my flat’. In contrast, and because Gwen’s historical circumstances differed Celia could not expect Gwen to have made the same stand with Rodin, though as always she queries Gwen about it, hoping for commonalities: ‘Perhaps you were equally strict with him, …’. [16]

Indeed this imaginative querying of Gwen becomes the means by which Paul shows the difference in her view of what constitutes imbalances of power in relationship. It is NOT because she see power imbalance in single-sex relationships (familial, social, and sexual kinds included) whereas Freud did not. For he did such imbalances, especially in gay male relationships as I tried to show in earlier blogs, including the one linked here. It is because she sees the interior life and the artist’s ability to reshape this, even in other people, in fiction and fact or any variation between the poles of that continuum. Hence I feel particularly that Cooke’s view of the book is especially wrong-headed when she says that she cannot quite overlook:

the rather fey idea of a one-sided conversation with a woman who died in 1939. When Paul writes as if John were a living, breathing friend – “I am excited that I have begun to communicate with you and don’t want there to be a pause just now” – something in me is embarrassed. [17]

That moment of bourgeois embarrassment is even more worrying when Cooke goes on to assert that she knows enough about Gwen John already from her reading in art to have this imagined version thrust upon her. This take misses completely the true dramatic and narrative novelty of Celia Paul’s book which in inventing a Gwen John out of scraps of letters and some biography, also gives her space and enough interiority to change as we follow that persona’s progress through this lovely book. The Gwen of the early book is like the early Celia in that book, who writes ‘NO ENTRY’ on her studio door, not to deter her son’s access because ‘he knew too well that rule – but for my own peace of mind’.[18] Likewise the early Gwen and the experimental first letters to her play on the cusp of a fear of not communicating across barriers between them. In looking at a photograph of Gwen with children, Celia says: ‘You are self-contained and remote. You also appear untouched and intact’.[19] Both the Immaculate Virgin then but also out of touch and untouchable – remote in time, space, and Celia’s efficacy of emotional capture. This is the Gwen seen by Dorelia McNeil, the lover of her brother Augustus who also became Gwen’s lover, as ‘extremely queer and hard … always attracted to the wrong people, for their beauty alone’.[20]

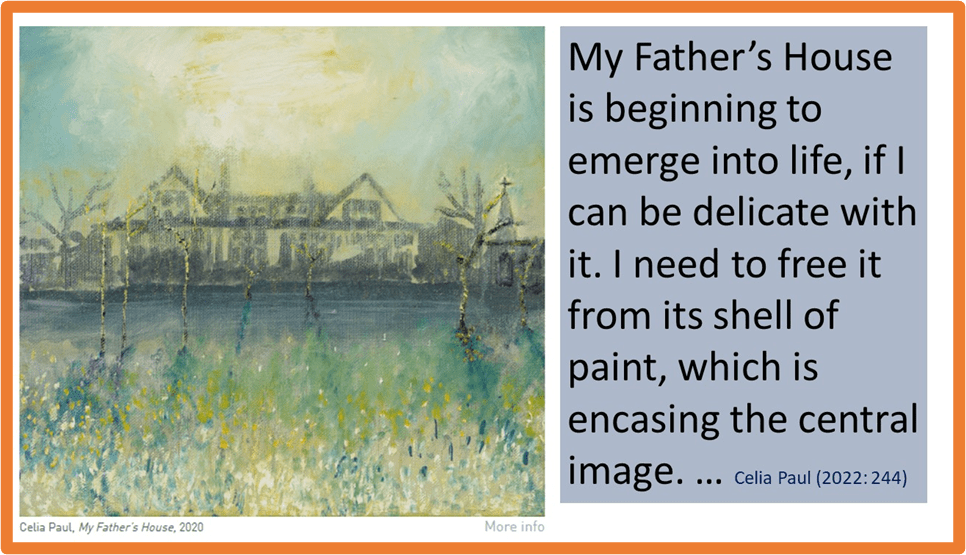

However, Gwen grows as Celia approaches her more closely. At one point one letter dies not end with a handshake in the masculine fashion (modelled after Vincent and Theo Van Gogh) but with a statement of love.[21] Some tentative closeness is more frequent, that includes other women too from past and present locations, such as Celia’s mother and the Brontë sisters. Eventually she pleads to Gwen to cast on her that ‘calm regard upon me, to steady me’ like the Virgin of the Catholic faith as a way back ‘My Father’s House’: a painting, yes, but also a primal place of love reflected and redeemed, restored delicately to life. And it is the act of writing to Gwen that helps her ‘articulate what I am aiming for’.[22]

In all, the power to which Celia aspires is one she sees or constructs in Gwen too – a power that is ‘completely still, and her stillness pervades the space around her’. She aligns this with the words from a Gwen John letter to her friend (a contemporary one to John rather than a future one like Paul), Ursula Tyrwhitt:

“As to me, I cannot imagine why my vision will have some value in the world – and yet I know it will … I think it will count because I am patient and recueille [collected] in some degree”. [23]

Rosemary Waugh for Art UK (online) mirrors these words in describing the peculiar power of magisterial paintings by Paul such as My Sisters In Mourning (2016).

The ethereal, smoky palette of chalky blues infused with sombre dove grey is shared with many of Paul’s more recent paintings, while the accents of straw yellow centred on the sitters’ faces echo traditional religious paintings. The title suggests the sisters are actively doing something – mourning – but the image itself demonstrates that to mourn is to be still, silent and reflective.[24]

There is more than a hint of what Celia Paul means here when she says, as I cited earlier: ‘I am interested in balances of power, but not of an obvious kind’. For the kind intended are those moments which replace the kind of spiritual and ethical power that was once the preserve of religion. The balance represented is the spiritual of known as atonement or, to make the analogy more obvious, ‘at-one-ment’. It is a kind of homecoming, in which reconciliation in one’s father’s house matters more than the causes of any original rift between those with unequal power – like the Prodigal Son with his Father. In the book this is represented by the constant recurrence towards its end of interpretations of the term ‘path’ and representations thereof, which Celia looks out for in Gwen’s painting and which are also associated with Celia’s dead mother: in the painting My Mother and the Mountain, the mother is represented as a path curling round the mountain. Paths become her motif Celia says. She says to Gwen:

You painted white paths with lines of grass running through the middle. You painted them in Meudon. Here, in your home county [Pembrokeshire], there are similar paths, bordered by bracken, everywhere. These paths feel significant for me. … The stream’s path leads definitely to the sea. But for man-made paths, the future is mysterious.[25]

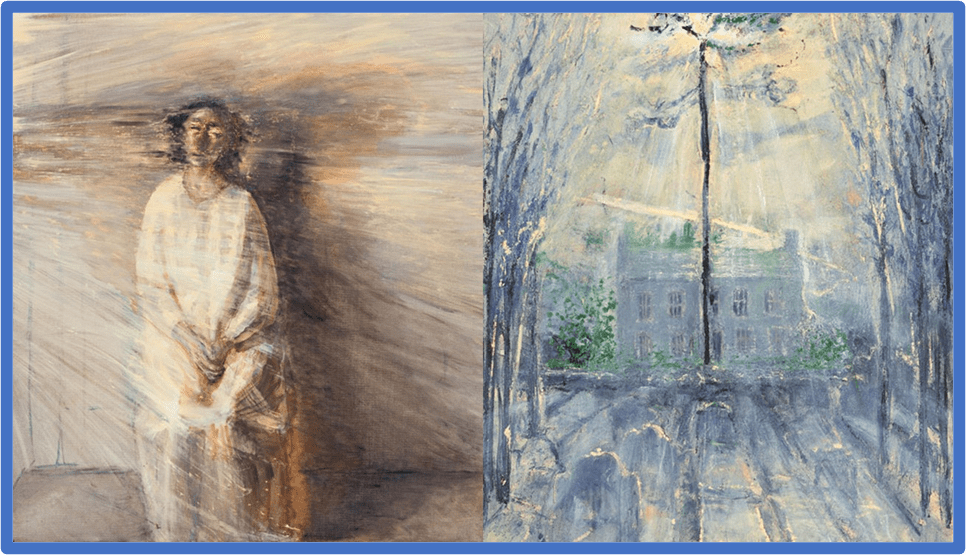

Paths and beams of transformative light cast upon the dead and dying in their graves are the subject of Celia’s painting, The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte’s Pine and Emily’s Path to the Moors) [2017]. In other paintings of her family the love which makes the figurative paintable, in Celia’s estimation, are like paths of light that obscure and abstract the figure in paintings of her mother and specially Kate in White, Spring .

Celia Paul (b.1959) Kate in White, Spring © the artist. Photo credit: courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro & The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte’s Pine and Emily’s Path to the Moors) 2017, oil on canvas © the artist. Photo credit: courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

This is presumably what was meant in Rosemary Waugh’s article on Paul, where she says:

In a 2019 interview with the Guardian, Paul explains how ‘It is quite telling of portraiture that love shines through. It is one of the reasons I know I can’t paint people I don’t love. If it works, it is only in a staged way’.

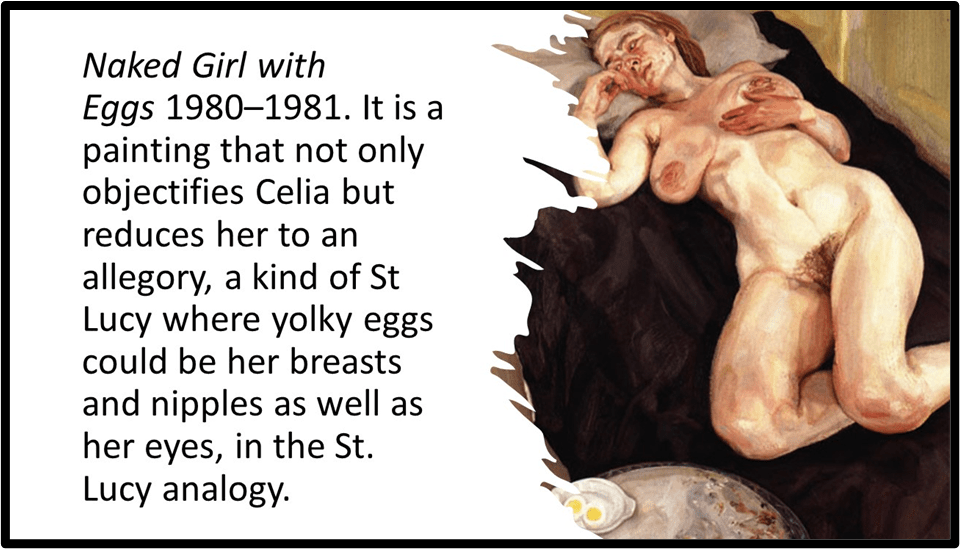

With that phrase ‘a staged way’ Celia has put into a context of sex/gender her critique of the method of great male artists like both Auguste Rodin and Lucian Freud who turn all human figures into objects presented to the eye as if on the stage, not least Celia in a painting like Naked Girl with Eggs 1980–1981. It is a painting that not only objectifies Celia but reduces her to an allegory, a kind of St Lucy where yolky eggs could be her breasts and nipples as well as her eyes, in the St. Lucy analogy.

The difference is that Freud draws figures without ‘love’, that ‘balance of power’ that is the equivalent of the atonement of less secular ages than ours. It is love that, after all, transforms the material in the spiritual, if we are to have such redemption at all in the twenty-first century. Do read this book. It is magnificent and beautiful in my view, as much so as the more cerebral Self-Portrait of 2019. It is a book that reminds those who need it that art by women casts new light on all art, perhaps redeeming some of it from its own coldness, by surrounding it with contexts that add grace to its materialistic fleshly subject matter, where that is possible. In Freud, I think it is, although such redemption needs narrative context that need not be biographical but must bring out its variations of humane temperature, including warmth. Perhaps though Naked Girl with Eggs will never get to that place where it warms rather than heats the blood like a fever.

All the best

Steve

[1] Celia Paul (2022: 164) Letters to Gwen John London, Jonathan Cape.

[2] ‘From the Acknowledgements’ in ibid: 338.

[3] Rachel Cooke (2022) ‘Letters to Gwen John by Celia Paul review – a woman in her own image’ in The Observer (online) (Mon 4 Apr 2022 07.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/apr/04/letters-to-gwen-john-by-celia-paul-review-a-woman-in-her-own-image

[4] Carole Burns (2023) ‘On Celia Paul and Gwen John’ in Wales Arts Review Online (DATE: 24.01.23) Available at: https://www.walesartsreview.org/carole-burns-on-celia-paul-and-gwen-john/

[5] Celia Paul op.cit: 124.

[6] Cited ibid: 103f.

[7] Ibid: 137

[8] Ibid: 254f.

[9] ibid: 164.

[10] Ibid: 181f.

[11] Ibid: 157f.

[12] Ibid: 338

[13] Carole Burns, op.cit. referring to Celia Paul op.cit: 241.

[14] Celia Paul op.cit: 140.

[15] Carole Burns, op.cit. referring to Celia Paul op.cit: 10f.

[16] Celia Paul op.cit: 107.

[17] Rachel Cooke, op.cit.

[18] Celia Paul op.cit: 46.

[19] Ibid: 84

[20] Ibid: 63

[21] Ibid: 173

[22] Ibid: 245

[23] Cited Ibid: 2

[24] Rosemary Waugh (2021) ‘The art of Celia Paul: a mistaken muse’, Blog Posted 03 Jun 2021 in Art UK (online) Available At: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-art-of-celia-paul-a-mistaken-muse

[25] Ibid: 289f.

One thought on “‘Since Rodin’s death, Gwen no longer needed to make an inviting space to entice a lover – this interior sounds as bare as my own’. This blog examines the uninviting space into which only ‘absent presences’ may enter. It is a very subjective reflection on power, sexuality and sex/gender in Celia Paul’s (2022) ‘Letters to Gwen John’.”