‘Could we all be living in our own fictions?’[1] This blog deals with a novel that evades identity politics and deconstructs black queer lives as if it were a work of phenomenological, existential, and psychoanalytically inspired philosophy. It is nevertheless a wonderful read. It is a blog on David Santos Donaldson (2021) Greenland: a novel New York, Amistad 35, Harper Collins Publishers.

The novelist, who is also a psychotherapist, and his book cover: Publisher’s pictures.

I wonder how many readers like me will be drawn to this novel by its well-publicised connection to the novels and life of E.M. Forster? How many of those moreover will have left it having found a novel that is quite unlike one of Forster’s highly crafted plots and play with the rounding of characters from the flatness of English stereotypes on which they depend? As Donaldson says in his ‘Acknowledgements’ that, even with Forster’s life as recorded in well known ‘historical works’ by Wendy Moffat and others, he has ‘in shaping this fiction’, ‘taken many liberties regarding inventing characters, ignoring others, and rearranging the timeline of historical events’.[2] In an interview with Ilana Masad in 2022 he has also said that Forster is a very complex kind of phenomenon from his list of literary and sexual-political influences and ‘loves’, a phenomenon that can ‘draw’ queer black men towards him and into him:

I also loved Forster’s work, and felt a little bit guilty falling in love with him, because he’s not too radical, he’s not Black. I was like, “I shouldn’t be loving this very British middle-class guy. So what’s drawing me to him?” There’s something there, something that drew Mohammed too.[3]

Of course there is nothing new in fictionalising literary biography, but this novel does more than that. One could explore this book entirely as a metafiction – a fiction about the nature of fiction. Talking to Ilana Massad, Donaldson may encourage that approach:

This novel is very meta. It’s a novel about a novelist writing a novel written by a novelist. It seems to mix genre: it’s fiction, it’s written almost like it’s memoir, and sometimes the protagonist goes off on a sort of an essay.[4]

However, that is limiting and such and academic approach perhaps. Rather we should consider that the novel proposes, as the cited quotation in my title emphasises that there is not much in the substance of the lives we live, or have lived, that is other than ‘fiction’, a layered repertoire even of what it sounds churlish to call ‘lies’ that take on the mask and persona of truth, through which personae we poor humans are able to know that truth or tell it to others. Mohammed El Adl, a character based on the tram driver in Alexandria with whom Forster fell in love of the same name but whose education far outstripped that of peers, thinks he can tell the truth to Edwin Morgan Forster. But what is the truth he tells: ‘To tell you the truth, though, I do not always tell the truth. Lies are sometimes necessary’.[5]

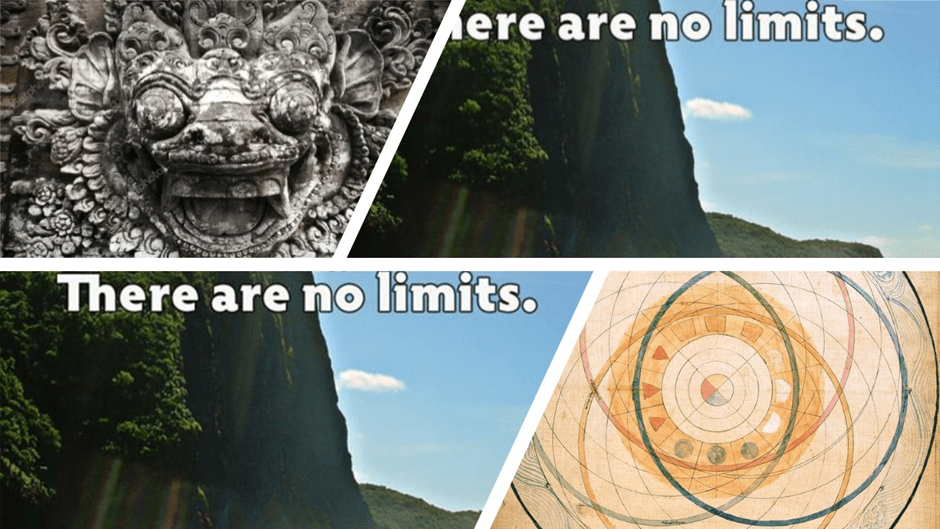

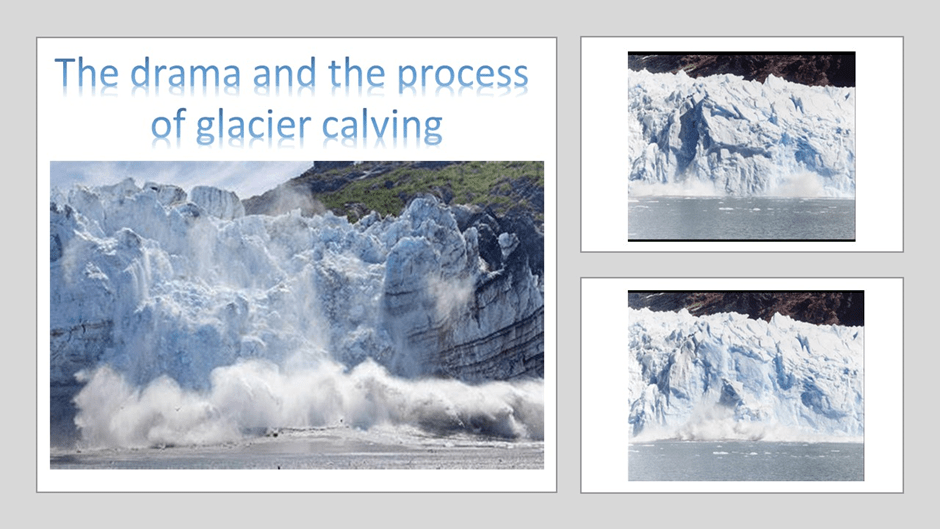

We so often read to discover the truth about the lives of individuals or even the truth of what it is to be a certain type of person, such as a black male queer man, but that aim is perhaps misguided. When asked in another interview, by Teddy Wayne, what his novel is about part Donaldson’s answer was: ‘One man screaming his truth, crashing boundaries as glaciers crumble and his true voice emerges with endless possibilities’.[6] That man is the narrator Mr Kipling Starling (more often known as Kip but named after the British colonial poet Rudyard Kipling). Yet the truth in this character is hardly distinct from stories implicit here in the metaphors Donaldson uses to characterise it, as a thing produced from terror, a ‘scream’, something destructive of safely defined borders and explosive in and of its nature, or like an ‘avalanche’ (an oft used metaphor). Truth is clearly something in part aligned with the stressful conditions of it being made possible – something that might in the ordinary run of lives, wherein emotion is carefully controlled and limited by necessity, be considered to be not full of ‘endless possibilities’ but ‘impossible’.

The novel itself explores this capacity to ‘see the impossible’ in a conversation that the narrator remembers from his time in an ‘ashram in Maharashtra’ with ‘another devotee, Soraya Agyeì’. The conjured ‘impossible’ is dubbed ‘magic’ in this conversation at first, a repository of the ‘mystery and the unknown in the world’. But later in the conversation Soraya says: ‘We can see what others call magic. But it is not magic. It is just the truth that others do not see – no boundaries of time and space’. The world known to conventional and limited wisdom or ‘fact’, without that surplus of multiple expressive counterfactuals ready to burst out from within it, is subject to social beliefs about the nature of time and space that define it and its terminology, which Soraya calls by the Sanskrit term Kāla. Kāla, ‘which roughly means Time and Space’, is she says: ‘an illusion due to one’s attachment to the fleeting cycles of a material world’. [7] Of course, Kala is a God of Death as well as of Time.

Other psychoanalytic psychoanalysts, such as Donaldson is, will, of course, find in such ideas the imagery of the Jungian Collective Unconscious. Early on he also uses a notion from Donald Winnicott’s object relations psychoanalytic theory, ‘a “transitional object”’ to ‘personify’ the ‘silly inanimate object’ that is his MacBook on which he writes his novel – the one about Mohammed and Forster – in order to see it, as he sees many other ‘invented/real’ characters in his story as the projected object catering to his own ‘needs for nurturing and support’.[8] A little later he invokes Carl Jung by name to characterise the Unconscious which ‘makes you do shit you don’t intend to’ and which is a ‘tricky little monster’. All the more pertinently the Unconscious is part of that near-invisible domain outside the ‘illusion of Time and Space’: ‘It sneaks up on you, and even when fully in its grip, you can hardly see it’.[9]

We need go no further than this to show that Donaldson’s novel is a highly ambitious one, and that the ‘shaping’ of ‘this fiction’ had much to do with its underlying philosophy of Time and Space (and their handmaiden ‘memory’, who blushes to associate with the imaginative counterfactuals of desire and, as yet, unknown possibilities) as illusions that barely allow for the presumption of a world that is distinct in being known as the ‘real’ or ‘true’, which are but material constructs too in that philosophy. Hence, some critics, find this a narrative that really does not satisfy their need for cogent and rational storytelling. Maureen Corrigan (2022) in npr says, for instance, that: ‘If these plotlines sound a little overheated, well, sometimes they are. In fact, I put the novel aside twice’. Corrigan may have been drawn back by the book’s humour but I sensed none of her resistance to its hot and pacy stories in my own reading.[10] In that, I agree, I think, with Bethanne Patrick in The Los Angeles Times, who says in her words:

This is a book with respect for neither the margins of the page nor those that confine us in the real world. Some may find its bountiful overflows confusing or unnecessary; I found them mostly captivating.[11]

My agreement with Patrick may be a matter of taste in story form but it is also somewhat more. Like her, I feel the pull of a lost tradition of the popular narrative which allows itself to be ‘crammed full of so many ideas and tropes that () threaten to spill out of its margins’ which she instances with Iris Murdoch’s The Philosopher’s Pupil. And as with Murdoch in this and other novels, undermining, bursting or causing to fall down conventional and normative boundaries of definition cannot, if authentic, be anything other than a ‘queering’ of the world, yielding a confusing buzz whilst the mind holds on to verities of which it dare not let go – what psychoanalysts might call psychological defence systems. Very often the novel equates this confusion with the term ‘noise’ – those background sounds that surround the audible voices of supposed articulate human discourse. In a novel where one novelists searches for his ‘own voice’ and for the distinctive one of Mohammed el Adl which it is his ‘main struggle’ to get ‘just right’, he learns that it may be enough not to have a defined voice that competes to be heard alone.[12] Instead we can but to contribute one’s individuality to a collective. In his interview with Teddy Wayne, Donaldson says of his own motivation for writing that is based on remembering that:

… no one else on this planet will have my exact same experiences, so if I don’t share my voice it will be forever lost. The world will never know it. So together, all of our voices make some kind of great song—maybe it’s beautiful and harmonious, or maybe it’s just an interesting noise. Doesn’t matter! It’s only about letting it out and joining the great universal choir (my italics).[13]

In the novel Kip ends says that he finally understands that, ‘Noise is all that matters!’ There is no need to find one’s voice, or even ‘to craft how I sound’ when mimicking the voice of Mohammed for he is responding really to the ‘entire fucked-up world’ including Shakespeare, Tolstoy … and, yes, Edwin Morgan Forster. It is only at this moment that he realises he doesn’t need ‘to be locked away and protected’ from the play of diverse voices, only to become part of their ‘straining and pulsating’ body, endlessly splitting and reintegrating, modelled on the noisy process of how a glacier births a calf.[14]

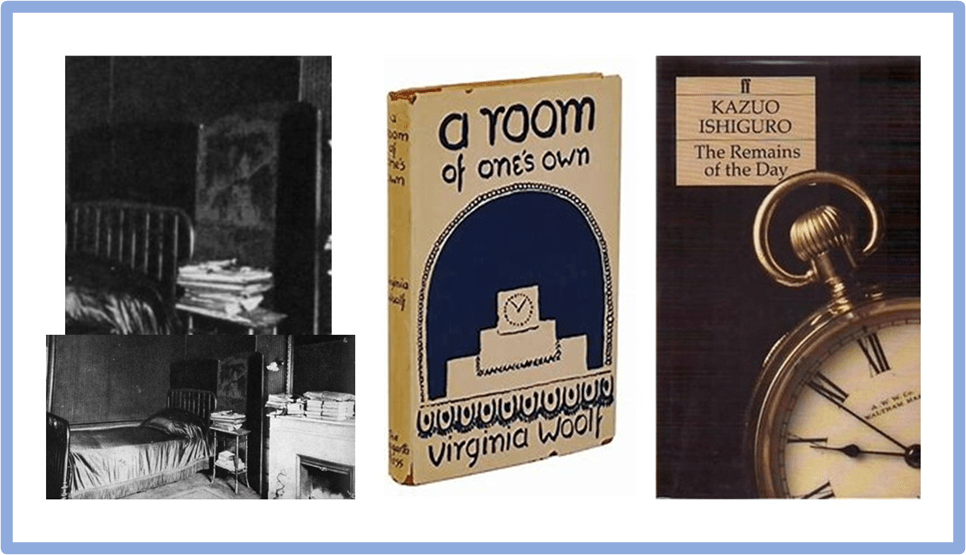

Prior to this understand this narrative plays continually with the ideas of ‘confined spaces’: time and space conditions that are built, or that we build ourselves, to create boundaries for margins of safety or fear of intrusion. Such boundaries exhaust all of Kip’s attention, just as they do both Mohammed and Forster. The feeling of how the passage of time is to be spatially handled to fit in the writing by Kip of his own novel is one example of how space (for time in narrative is a space too quite obviously) limitations feed into Greenland’s structure. Similarly Scheherazade’s circumstances and needs as a narrator and subject of her story, to delay the progress towards timely endings, feed, as Forster tells Mohammed, into the structure of her stories as managed time – the stories of One Thousand and One Nights.[15] Hence, people feel, in this novel, continually led into ‘traps’ or other confined spaces of real, imagined or self-imposed imprisonment. It is from a state of ‘being locked up in this cramped basement study’ that Kip starts his revision of his novel, which story itself starts from Mohammed’s incarceration in an Egyptian cell In Alexandria. A confined space seems needed to allow him to focus on the confined limits of time allowed to him to write it: ‘Three weeks is all I have for this entire crazy endeavour’.[16] And the authority of other writers who used confinement in time and/or space is invoked too, as if writing were necessarily a shutting oneself away from otherness physically and mentally: writers and their writing cells including Proust’s cork-lined room, Virginia Wool’s room of one’s own and the self-imposed limitations of time of Ishiguro to write the relevantly named The Remains of the Day.[17] Of course a confined space is also a ‘closet’, the first place Kip hid himself away from parents whose limitations let him down.[18]

There is a constant riff throughout the novel on ideas of the confined and contained that continually plays against the idea of the unconfined and uncontained as if it were its binary: especially in the idea of the ‘wilderness’, a place, for instance, where Jesus ‘wrestled with the devil’. Both kinds of space indicate the potential to isolation and hence they are binaries that actually often become mirror images of each other. The classic version of this elision of binaries into a range of means of shutting out the otherness of the world is the Arctic tundra of the country Greenland with at its centre, an ‘igloo’ one builds for oneself (or with one’s ‘double’). In the confluence of these two other binaries collapse such as those between heat and cold – it is ‘warm enough’ to shed an ‘anorak’ inside an ice igloo – or between freedom and imprisonment.[19] The play of these binary signifiers runs through the novel as they negate each other’s difference and insist that each defines the others illusory nature against the queer flux between differences that makes us part of the ‘noise’ of everyday life. Once Kip decides that his novel of Mohammed must start from a ‘cage or a jail’, but it is one where Mohammed muses on the ‘icy sting’ that also ‘scorched’ which he feared and desired as if he were a fearsome portal to a new life. But that new life is already in this hot smelly cell evoking the life of an Eskimo escaping ‘ice and freezing winds’ in an ‘igloo’.

Yet such securities – of the wilderness or a cell with permeable boundaries (doors against which no amount of stacked furniture saves one from your needs) are prone to threat of flood, collapse or ‘avalanche’. Proust cooped himself up in a bedroom’ but was ‘overtaken by memories, the avalanche’.[20] Mohammed in his cell smells the flowing liquid and solid waste of too much civilization (and of the moody Nile) in the culverts of the city: ‘heavenly showers and filthy fluids – the great blessings of Osiris’. [21] A wonderful outburst of Kip’s is against an operative (‘a nice, waiflike kid’) of ‘The Container Store’, who clearly does not understand the issues when he insists to kip, on behalf of his store and to sell the writer a ‘container’: “Whatever you need to contain, we’ve got a container for you here’. In psychoanalytic theories good enough mothers act to contain overwhelming feelings in their infants and a good therapist models this behaviour with the analysand. But, as Kip says the overflow, avalanche and outburst of rage is an ‘unfathomable’ flood. [22] It is perhaps the same flood Mohammed fears in Alexandria – the one whose type drowned his brother Ahmed and with renewal of life brings death, just as Mohammed fears loving a white man like Forster will do, provided you are a type of Osiris who also has an Isis, whose love resurrected her lover.[23]

At the heart of this novel is a key concept in the philosophy of psychology – the drama of the origins, maintenance and boundaries of identity. And the novel struggles with getting the voice of marginalised persons (writers sometimes) ‘just right’ as Kip worries about getting his narrative voice -0 his own and Mohammed – ‘just right’. Modern philosophy, whether in the thinking of Derek Parfit or queer theory, to name just two alternatives, has displaced the issue of aiming to find the true identity behind markers such as being black, being gay, being a man or woman. Instead it accepts being as an acceptance of metamorphosis – that accepts boundary intrusion and reformulation, even death and resurrection (even as an idea), and change within communal contexts of collective security. It no longer fetishes the individual as an identity. This is the Walt Whitman ideal option, provided we do not confute the poetry of The Song of Myself with the song of one man and one body alone but a social and collective body: love transforms selves, multiple loves transform them multiply and continually across many boundaries. Hence, Ben quotes to Kip (perhaps not knowing its full meaning) this:

I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.[24]

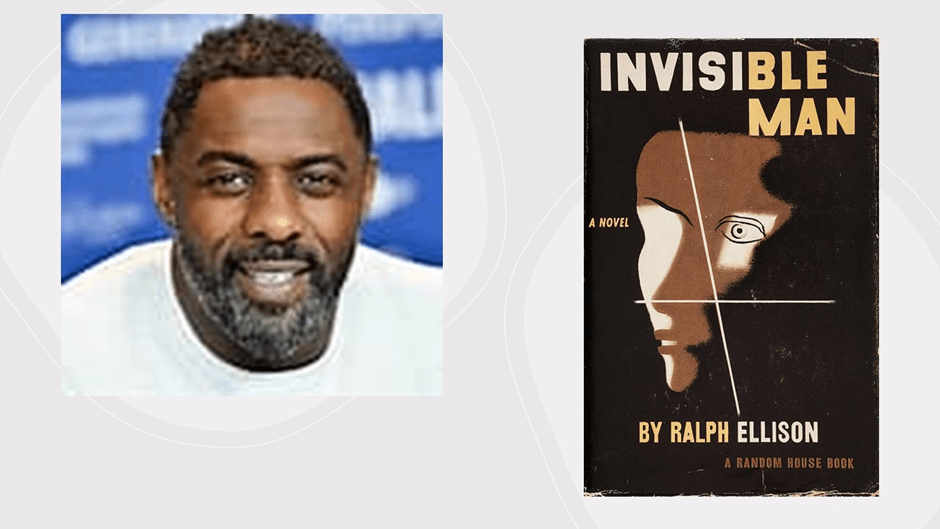

Electricity and song are both metaphors used to create connection in this novel not only between persons but the different partial identities of one person as they fuse into one being, as in the fusion of Kip and Mohammed in the final pages.[25] It is a image of power as well as a powerful image because it is about how people become whole beyond partial identities and the false boundaries of social and normative convention. The theme is one of recognition, for in this novel the partiality of identity which stems from single non-intersecting or over lapping identity markers is clearly the route to isolation and anomie. As a student, Kip is unable to be recognised in any satisfactory wat because in each case identities class – his English background and language is distinct from white Americans and more so from black Americans, and particularly queer Black Americans. He is there a ‘Nowhere Man’: unlocated in a comfortable time, space or being. Gay and Black Kip still is told that his university black queer group is ‘a Black gay thang – you wouldn’t understand!”[26] Here as elsewhere, Kip is like Ralph Ellison’s hero Invisible Man, never ‘seen’ because never understood nor thought capable of understanding what it means to feel at home in his own skin. Entitled white friends see him as a ‘person’ not as Black, but as he says: ‘I am Black, so if you don’t see that, you don’t really see me!’[27] Being unseen is not only being an alien but homeless – the Caribbean-English word for which is the ‘Nowhere Man’, in which ‘identity’ Kip also finds himself, if you can be a self if you aren’t seen and are nowhere.[28] He finds himself indeed only in another – at first in the English actor, Idris Elba. Before Idris:

I’ve also never been able to see myself as I really am – just as they haven’t been able to see me. I’ve internalized their distorted vision of me.[29]

And it is in mirrors of otherness (particularly in the eyes of the other – though not in the ‘white gaze’ which invalidates him) that he finds himself, though he must look outside of his present circumstance where he might find it in the struggle to create alternative possibilities in life – In Mohammed certainly whose eyes form his final mirror but also in the struggles of E.M. Forster – perhaps even in Ben, his husband, though the court remains out at the end of the novel. The first discoverer of these truths is Mohammed with Forster, through the fact of understanding that he call love another as himself, his double other – a self that can be seen but not seen by the beloved but by the self itself, recognizing that it is capable of loving outside itself.

…; it was I who had seen myself when I thought he had seen me. … I had needed Morgan to see myself. … And yet, the goodness I saw in myself was true. I was capable of giving love, being loved – that was real. Is all of Life only a trick, an illusion like this? Are we all walking through a hall of mirrors, reacting to our own reflections as if they were our enemies, our teachers, our lovers? Could we all be living in our own fictions?[30]

I started this piece in my title with the last sentence here. Put baldly here a ‘hall of mirrors’ is a nightmare place, but, in a sense, the novel will try to establish, it is also a place of hope, where fiction can redeem us, providing we do not trap ourselves in stories confined to the conventions of time, space and geographic local space and history most of all. Travel across time and space opens up fiction to new alternatives, to possibilities. The richest expression of this is where Kip looks into the eyes of Mohammed who is both the Mohammed of Alexandria and is not – instead a Mohammed from Morocco. But the confluence of stories is mirrored when each see each other mirrored in each other’s eyes. The passage is a long one and needs reading carefully. In Mohammed’s eyes reflecting himself though Kip sees new worlds floating in the ‘entire universe’ he also sees around it, where any story, any fiction, is a possible truth, part of a series of counterfactual worlds: ‘And now I see everything there is possibly to see. … And everything in the universe is looking at me’.[31] We should note the phrase here ‘everything there is possible to see’. The key word is possible. In this abstraction of whole worlds are the possibilities (for Forster, of course, possibilities of ‘only connecting’) – stories which can end in any possible way and manage any possible character of multiple intersecting aetiologies of character or personality in the world – of race, culture, language, spirituality, sex/gender and sexual being. When asked how he would summarize his novel without using sentences, Donaldson used a phrase I have already quoted about ‘one man screaming his truth’, but as well as this cataclysmic discovery by one man, his summary was – and these are the first phrases used: ‘Trying to find love in the face of dehumanizing forces. Writing as salvation for a queer Black man. Mining colonial histories and tackling Whiteness’.[32]

Bethanne Patrick also says of the novel however, that:

Amid all this is a lot of sex — all of it meaningful in Donaldson’s hands. One man refuses to let Kip penetrate him, saying he’s saving himself for their wedding night. He declares his love by giving Kip a Glock 22, a gun as Chekhovian as they come.

I am not sure that there is ‘a lot of sex’ in these pages though. There is sex, but I think it is rather an interaction fitted into the paradigms of the novel related to control or loss of control – hence the symbolic importance of the gun, which appears on the first page of the novel but is not explained until tied to Kip’s affair with the American policeman Gus. Controlling wildness segues into themes contrasting confinement, for some crime of unimaginable proportion, and free space in a wilderness. These terms, for instance describe contradictions in Kip’s husband Ben whose sexual practice was based on ‘ability to abandon all control’ but whose counter ability to ‘take control when he wanted’ fascinate Kip not only because they provided openings to fulfil his ‘basest will’ on the proffered body of Ben.[33]

Kip admires loss of control that yields to control again at will. For him the problem is control of the openings memories create even in confined spaces to overwhelm him in the conflicting stories of the selves of which he is made up. Sex is butt one of those stories: Memories seem impossible to control. Like stones in a pile, I cannot pick out just one without causing an avalanche’.[34] You will enjoy this novel if you can allow for control to e a little abandoned, but if you can allow yourself the threat of the collapse of all you knew or thought in a flood or avalanche, you will love it as I do. It is a great queer novel in the widest sense of queer, wherein sexual relationship is only one factor in our being not the whole.

Do read it!

All my love

Steve

[1] David Santos Donaldson (2021: 267) Greenland: a novel New York, Amistad 35, Harper Collins Publishers.

[2] Ibid: 319

[3] Davidson cited in an interview with Ilana Masad (2022) ‘Read Me: This Debut Novel Is a Meta Story About Historic Queer Love’ in Them (online) [June 7, 2022] Available at: https://www.them.us/story/read-me-david-santos-donaldson-greenland-book-q-and-a

[4] Ibid.

[5] David Santos Donaldson op.cit: 62 (Donaldson’s italics).

[6] Davidson cited in an interview with Teddy Wayne (2022) ‘Lit Hub Asks: 5 Writers, 7 Questions, No Wrong Answers: Featuring Sopan Deb, David Santos Donaldson, and More!’ in Literary Hub (online) [July 12, 2022] Available at: https://lithub.com/lit-hub-asks-5-writers-7-questions-no-wrong-answers-july2022/

[7] All citations from the chapter ‘Soraya and the Stars’ in David Santos Donaldson op.cit: 201 – 206.

[8] Ibid: 17

[9] Ibid: 36

[10] Maureen Corrigan (2022) in npr (online) [June 14, 2022, 10:53 AM ET] ‘Greenland’ revives E.M. Forster — and spins a tale of racism and self-discovery’. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2022/06/14/1104835991/greenland-review-david-santos-donaldson-novel-e-m-forster

[11] Bethanne Patrick (2022) ‘Review: A Black gay novelist explodes the margins, with help from E.M. Forster, in Greenland’ in The Los Angeles Times (Online) [JUNE 8, 2022 6 AM PT] Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2022-06-08/a-black-gay-novelist-explodes-the-margins-with-help-from-e-m-forster-in-greenland

[12] David Santos Donaldson op.cit: 37.

[13] Teddy Wayne op.cit.

[14] David Santos Donaldson op.cit: 316ff.

[15] ibid: 40f.

[16] Ibid: 7 & 3, respectively.

[17] Ibid: 15f.

[18] Ibid: 34

[19] Ibid: 299f.

[20] Ibid: 25

[21] Ibid: 21

[22] Ibid: 44

[23] Ibid: 107

[24] Cited ibid:122.

[25] Ibid: 317

[26] Ibid: 79

[27] Ibid: 82

[28] Ibid: 150.

[29] Ibid: 181

[30] Ibid: 267

[31] Ibid: 310

[32] Teddy Wayne, op.cit.

[33] David Santos Donaldson op.cit: 49.

[34] Ibid: 25

One thought on “‘Could we all be living in our own fictions?’ This blog deals with a novel that evades identity politics and deconstructs black queer lives as if it were a work of phenomenological, existential, and psychoanalytically inspired philosophy. It is nevertheless a wonderful read. It is a blog on David Santos Donaldson (2021) ‘Greenland: a novel’.”