‘Men sprawled over each other. In the hypermasculine atmosphere of war, they were not overly concerned with manliness’.[1] This blog focuses on the treatment of sex and /or love between boys who become men in a time of international war, with a discursion into presentation of those themes as poetry. This blog is on Alice Winn (2023) In Memoriam Viking (Penguin Random House).

The USA & GB cover with Alice Winn

When you read through short reviews of Alice Winn’s novel In Memoriam you find it most often seen as either a chronicle of ’forbidden love’ in the early twentieth century or a passionate reflection on war itself; ‘a vivid rendering of the madness and legacy of the first world war’ in Hephzibah Anderson’s words.[2] Whilst aware that Winn herself has written about her novel describing its representation of ‘forbidden love’, I balk at this cliché.[3] To me, at least, it doesn’t reflect the novel’s honesty and openness at its best, whilst suggesting that oppression is the source of ‘the romantic’ in and of itself. Nevertheless, I suppose that, in some sense it was something of this salacious sort of narrative impulse that allowed me to race through this novel, with its clear and simple style and convincingly realistic dialogue (for the rather unreal public school characters – unreal for an aged working class grammar school boy – who form its main cast of characters). At times I felt the public school milieu very near to possible pastiche but that may be that I have never been to Marlborough School, on which Preshute School in the novel is based, which Winn has. There is very little that presents itself as ‘forbidden’ in the subject matter of this novel except in that it purposively and consciously expressed things an earlier novel of public school life would not disclose without some sort of self-censorship or coded reference. To see what that looks like you might read E.F. Benson’s David Blaize , for instance, which almost break cover as an earlier blog of mine has already suggested – access this blog through the link).

What contributed to my joy, and pace, in read was matter often liberatory rather than expressive of the forbidden. This is a novel which provides a kind of ‘queer romantic’ generic feel, where both the tension between, and confluence of, overt sexual feeling and romantic love are as open to inspection and consumption by queer men as they are in hegemonic heteronormative romantic fiction for women. It is neither pornography nor a cleaned up discourse of love that might be described as asexual – in its description at least – but in some tense place between these possibilities. Indeed those options are identifiable in the novel’s own reference to the reading done by its characters, especially that reading which feeds the own need for a model of male-to-male ‘romance’. The apparently asexual option to describe love between men is seen at its most prominent by Ellwood in his description of the ‘sexless Tennyson way’ of writing.[4] Ellwood diagnoses this manner of representation of male-to-male love as that, for instance, of Tennyson’s 1850 masterwork In Memoriam A.H.H., This poem is a song of love to the dead Arthur Hallam. It is made appropriate to the novel not just because of the latter’s title (though that title refers to more than the Tennyson text alone) but also because just as Hallam was affianced to Tennyson’s own sister, Ellwood also felt himself promised in marriage to Henry Gaunt’s sister Maud (named after Tennyson’s 1855 poem, Maud).

Tennyson, the poem In Memoriam A.H.H. and its subject Arthur Henry Hallam.

Such parallels are more than deliberate in this novel. However, if Tennyson provides a ‘sexless’ model of male romantic feeling, there is much that is a long way from ‘sexless’ in writing about love and physical contact between males in this novel. For instance, choices between oral and anal sex are clearly indicated both for the boys at Preshute who took part in such romances, which seems to be most boys in the novel, and those same boys grown into adult soldiers. The facts of oral sex, even Ellwood noticing in the process of his lover th at his {Gaunt’s] ‘prick was a little smaller than his’, are given moments of perception between the two men, as are, in these relationships as they develop, the choice of positions lovers and experimenters alike choose in anal sex.[5] The acknowledgement of how men negotiate the pain involved in graceless anal sex is acknowledged in the latter openly and continues to be referenced without deceptive or self-censoring disguise throughout the novel moreover, as in the beautiful scene wherein Gaunt allows himself to suffer more pain than is necessary in anal sex with Ellwood as a means of manifesting the submissiveness of his love to Ellwood. That this self-elected choice of pain also is seen as a reflection of the brutality both men have observed in the battlefields of Ypres and the Somme, adds even more depth and openness to the depiction of raw sexual honesty in modelling male relationships I think.

War seems a pre-condition of the specifics of the kind of complex love relationship between these two men; with the potential of an acknowledge mutual pleasure in a kiss, for instance, being, as Henry Gaunt thinks to himself as he probes the fall of the defensive system he calls his masculinity, being possible because men in War contexts act by different cognitive scripts: ‘It was only because he knew he would die that he could be reckless with [his heart]’.[6] That this novel is set in war is perhaps too an addition to that romance in that it tests the porousness of sex/gender identifications. War, after all, provides easy images of masculine stereotypes (at least to those not in it) but because it creates a realm of male attachment where both romantic love and sexual experiment between men might become part of the world for more than a few men singled out from others as ‘homosexual’ or gay. Its contrast between the world of men at war and an unknowing home life (heteronormative even down to the creation of special cases for intermale sex and brief and probably ‘illusory’ love in specific times and places – such as the phase of public school) is also one that acknowledges the mediation of law into the lives of men in love, if that love is to be public, as in this moment: ‘Gaunt wished he could tell him he loved him, but they were in public, and it was illegal’.[7] We need to return to the exploration of masculinity in war later, for that is my main theme in this blog, but first a digression on reflections of male love in poetry seems appropriate.

In part I do this because Hephzibah Anderson also characterises the representation pf the war years in this book by terming it a picture of the Siegfried Sassoon generation (for Sassoon is cited much as is clear in the book’s ‘Acknowledgements’ of where in it Sassoon’s has silently (in the text itself) formed the source of literary borrowings. And this is another reason why I love this book – because it reflects men, masculinity and active ‘passion’ in war using issues related to shifts in poetry from the High Victorian example of Tennyson to the wasteland portraits of war in the otherwise unmentioned Sassoon. Ellwood changes not only as a man but as a writer, who once aped Tennysonian forms – including the stanza forms and characteristic assonantal sound-effects of the master to someone who might perhaps write more like Wilfred Owen. She says:

Ellwood is partly inspired by Siegfried Sassoon, for instance, while the ghosts of the young men Vera Brittain lost never feel far away. This is the conflict depicted from a 21st-century perspective, however; the novel’s increasingly pacifist protagonists certainly have no time for Rupert Brooke’s “bone-chillingly soppy” verse.[8]

Ellwood actively rejects Tennyson as a writer about war, for instance, in the novels constant play with his poem, The Charge of the Light Brigade, which is quoted in full as an addendum to a mock copy of the school ‘Roll of Honour’ of the glorious First World War dead.[9] This appearance is a heavy handed irony in response to the poem’s appearance as a favourite of the novels ‘cast’ when they are younger boys, although even here it is not seen as an example of good or significant poetry, but rather as setting the imagined context of boys fighting with extended rulers (rather than sabres) and recited even by a Tennyson aficionado like Ellwood only ‘when he was too tired to be interesting’, for the poem was, as the novel’s authorial voice insists known by ‘every English schoolboy’.[10] For that very reason it is referred to later by these schoolboys turned soldiers only with extreme irony, where Rupert Brooke’s fate is also likewise ironically cited.[11] At his most Sassoon like Ellwood rejects not only Rupert Brooke’s jingoistic poem The Soldier but the Tennyson poem it came from thus:

“… – isn’t it funny how that has changed, how two years ago we wanted nothing more than Rupert Brooke and – “ he stumbled, he had clearly been about to quote from “The Soldier”, but he never quoted poetry any more. “- and, and, all that sort of heroic stuff about dying for glory, but now all you’ve got to do is describe how much blood spills out of a chap when his stomach’s been torn out by shrapnel …”[12]

Things are somewhat different when we come to the silent and implicit evaluation of the language Tennyson offered to men to think about the subjective aspects for the love of each other, in body as in mind and heart in the novel. These references are both much more nuanced, for I think Alice Winn both knows her Tennyson well and understand its centrality to the understanding of masculinity in Victorian England, and differentiate the reaction of different characters in ways that ‘round’ them, as characters, further. The next section of this blog therefore is about the novels’ wide reference to the complex sensibility of Tennyson, especially, but not only, in its first section.

To understand her use of the poet I think we have to also be sensitive that Ellwood does not represent the voice of Tennyson in the novel. Abandoning him for a more visceral poetry, even at the height of his attempt to model himself on Tennyson, Ellwood’s grasp of the emotional depth of Tennyson’s love poetry is extremely limited compared to the less articulate love of it of Henry Gaunt, the man Ellwood believes he loves. We can examine this, for instance, in the following passage, for it is full of the most stunning ironies in relation to Ellwood’s blindness to self and others. This failure to see the ‘other’ is because his readings stay, as it were, on the surface of readable phenomena in the world, including the reading of the written letter. At this moment of the novel Gaunt is still performing a butch masculinity associated with fascination with gritty fascination with pursuits such as boxing, though the boys are discussing schoolmates of theirs who had been expelled for being caught in bed with each other, of one whom Gaunt says, “Sandys is a damned fool”. What follows is entirely the interpreting vision of Gaunt through the point of view of Ellwood:

Yes, Gaunt thought Ellwood was a fool, all right. Although he had closed his eyes when Ellwood touched his face on Fox’s bridge; leant forward as if he wanted to be kissed … But Ellwood knew from experience how easy it was to convince himself that Gaunt was secretly pining for him, and it was a theory that didn’t hold up. …

Well, they hadn’t done anything that friends couldn’t do. He had not entirely given himself away. Ye, the gentle cheekbone kiss had been intimate (he could feel his face get hot as he remembered it), but it was still within the realms of masculine affection. If Tennyson could get away with writing poetry about Hallam for seventeen years, Ellwood could certainly kiss his closest friend on the cheek to comfort him. Although Gaunt had obviously been repelled, since he had fled into the army.[13]

The passage oozes ironies as Ellwood shows how little grasp he has of reading deeper psychological states than the binaries which support notions like determining what is declared openly as opposed to what is not and thence secreted, as if these binaries were merely either correct or incorrect readings of reality, with no sense of what might be lost to immediate consciousness and only dimly known if at all. Ellwood’s interpretations are ironically shallow inversions of truths that the novel will later reveal. We will know, already know now if we are reading carefully, that Gaunt loves Ellwood and that he had not only welcomed the latter’s kiss but wanted more, though he could not entirely know (openly in a way that convinced himself) he wanted that. It is thence more than ironic that it is Ellwood who seems to play games with what is, and what is not, perceptible as a socially permissible show of ‘masculine affection’. Likewise Tennyson’s love for Hallam is seen as something entirely shallow, something the poet ‘could get away with’ as if in a social game. Tennyson’s attempt to grasp the ‘otherness’ of Hallam hence remains missed, in the narcissistic play of one’s own feelings.

It is not only that psychologically deeper (or perhaps even just emotionally more complex and nuanced) reading would see that Ellwood’s perceptions are as shallow as the kinds of possible love that alone Ellwood recognises in the world. He sees either sexual feeling or romantic love wherein the mix of both in a range of responses must be unseen. His adept ability at bedding other boys is not a contradiction to his more special affection for Gaunt, though the latter is hardly deeper or more solid. In contrast the absent consciousness (or point of view) in this passage is that of Gaunt, who keeps his counsel even imperceptible sometimes to himself, but which runs in a deeper current and more silently. I think this is why Winn often gives clues to the reader that though Ellwood talks on and on about Tennyson, and apparently like (in a superficial way) Tennyson as a poet, the one who reads him most persistently and continuingly, even if the most apparently impossible circumstances is Gaunt. For instance, cut off entirely from Ellwood, having escaped a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany Gaunt wanders Amsterdam, ‘’with a friend’, his fellow escapee, Pritchard. The potential of affection between the men (for which there is no necessity for a label) is packed into what is NOT said in the prose and in its lyrical metaphors and musical rhythm, very underplayed:

They watched the lamplight reflect on the quiet water of the canal.

“This is enough, just now,” said Gaunt.

“Amsterdam, at night, with a friend,” said Pritchard.

They did not speak again. The peaceful loveliness of the night absorbed them completely.

A grey dawn broke, and the noise of life began again. They did not return to the hotel – they had nothing they wished to bring with them. They wandered loosely to the train station ….[14]

Lovely in itself, what this captures is a gentleness of bond that far outstrips Ellwood’s expectations of how love manifests itself, and it is full of nuance at the very deepest level, for it echoes the famous Lyric VII from Tennyson’s In Memoriam.

This echo therefore is able to suggest Gaunt’s readiness to accept affection from men, even from Pritchard, according to its specific and contextual meaning. It is deep in part because it registers too the absence of a more persistent loved one (Ellwood) in the echo of Lyric VII, which is the bleakest of the whole poems’ lyrics and which nevertheless, despite the stasis of the feelings, registers that the poet’s persona, the I-voice, must accept the life continues, that ‘the noise of life’ MUST restart in him. But it also takes Tennyson’s melancholy and cleans it into a gentle acceptance that awaits Ellwood’s hand more hopefully. Ellwood, after all unlike Hallam, is not known already to be dead. Such a resurgence of Tennyson, but in the consciousness of Gaunt not Ellwood tells us much about the revalidation of romance as a potential for men, that goes much deeper than Ellwood has yet dug into his feelings and thoughts.

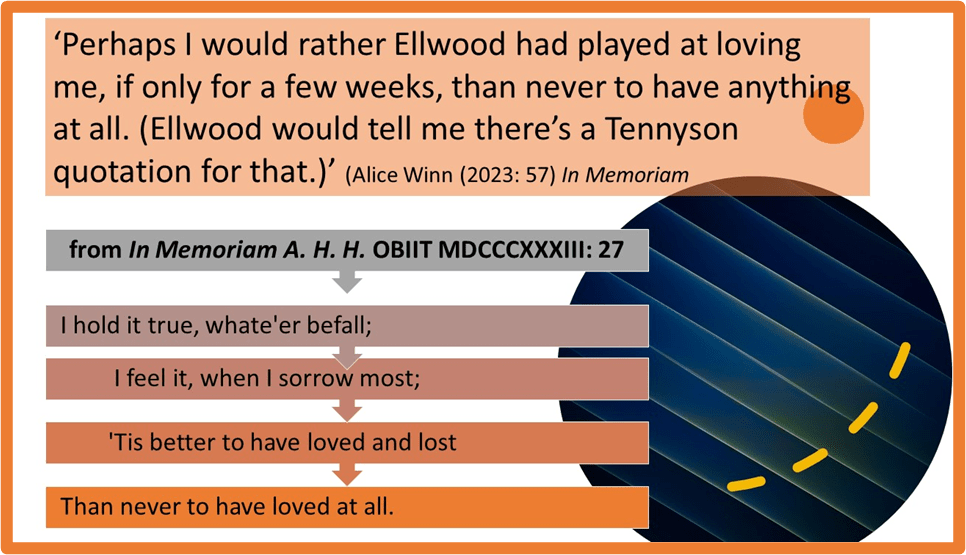

This is even so, when as a young man Gaunt writes from the trenches to Sandys, soon to be killed in action, in a way that not only references Tennyson but shows he knows the poem better than his pretender to (and ‘player’ of) love of the poetic in Ellwood. He writes: ‘Perhaps I would rather Ellwood had played at loving me, if only for a few weeks, than never to have anything at all. (Ellwood would tell me there’s a Tennyson quotation for that.)’[15] And so there is, from the final stanza of Lyric XXVII, perhaps the most well-known and carelessly repeated quotations ever. That Gaunt pretends not to know (for that is how I read it) the quotation is significant. That Henry conceals his own love and knowledge of Tennyson from Ellwood is even made clear in the novel when Maud corrects Ellwood’s beliefs about that issue, after Henry has gone missing presumed dead. He says to her:

“Henry hated Tennyson.”

“He can’t have done,” said Maud. “It’s all he read in the holidays.”[16]

For his loss of Ellwood’s love, as Henry thinks of in his schooldays hangs not only that they are parted by him enlisting to the War. His words also hint at the shallowness of Ellwood as a boy lover – someone who only ‘played at loving me’ – for one plays not only a role but a game. Gaunt, of course, does not know that Ellwood believes that Gaunt is special to him, but the fact that any such an opinion in the mind and heart of such a man is unlikely to run deep is a deeper knowledge that Gaunt holds of this boy-actor. When Gaunt still feels this deceptive love better than never having been loved at all by Ellwood, he is showing that the value of love as an imaginative activity can outstrip its object; an object which can be lost to childish vanity as well as to death.

Winn gives many clues to this reading of this one aspect (his), as it were for Winn herself compares what she achieves to the structure of Greek tragedy) of Ellwood’s character (old-fashioned rounded character stuff but I love it when it is done well).[17] Here is a good example when she refers to Ellwood in a hotel before returning to the trenches as being ‘curled up on the window seat, using his copy of In Memoriam A.H.H as a surface on which to write a letter’.[18] That this poem acts merely as a surface is telling here. It enables us to read more deeply those bits of the novel wherein the two men, lovers beneath everything, react to Tennyson’s word. Ellwood uses Tennyson as a medium for flirtation, an invitation to sex or even its prequel. When he uses a reading of Tennyson to, frankly, ‘come on’ to Henry Gaunt, he does this whilst labelling Tennyson as ‘a homosexual’.[19] It is but one step from the schoolboy fascination, recorded earlier in the novel of labelling Byron a ‘sodomite’.[20]

We have seen already above that Gaunt’s consciousness holds deeply within it Lyric VII and what it suggests about love as an emotional construct held deep within the lover and not dependent on the existence of its love-object in any tangible way, a difficult but essential thought in the ethics of loving. There is a beautiful moment when a citation of this Lyric occurs prior to the example I looked at above which I see as pointing the contrast between Gaunt and Ellwood. Ellwood, in the dark night, quotes aloud from stanza 2 (see above) of that lyric. It is important to see here how Gaunt suppresses from Ellwood that he already knows this poem: ‘“Tennyson?” Asked Gaunt, although he knew the answer’. The conversation that follows is difficult to interpret without invoking deep emotional nuance in which both men become angry about Gaunt’s question: “Will you write about me when I die, Elly!” It’s a nuance that evokes a kind of painful laughter that invokes all kinds of futures hidden under jokes. For instance, Henry asks in mocking tone: “Pray, o illustrious poet, how you will versify fucking me?” Ellwood’s answers in a way that is only in part a joke about Tennyson’s imagined sexuality and its representation in his poetry: “Maybe I’ll just change your name to Maud and be done with it”. [21]

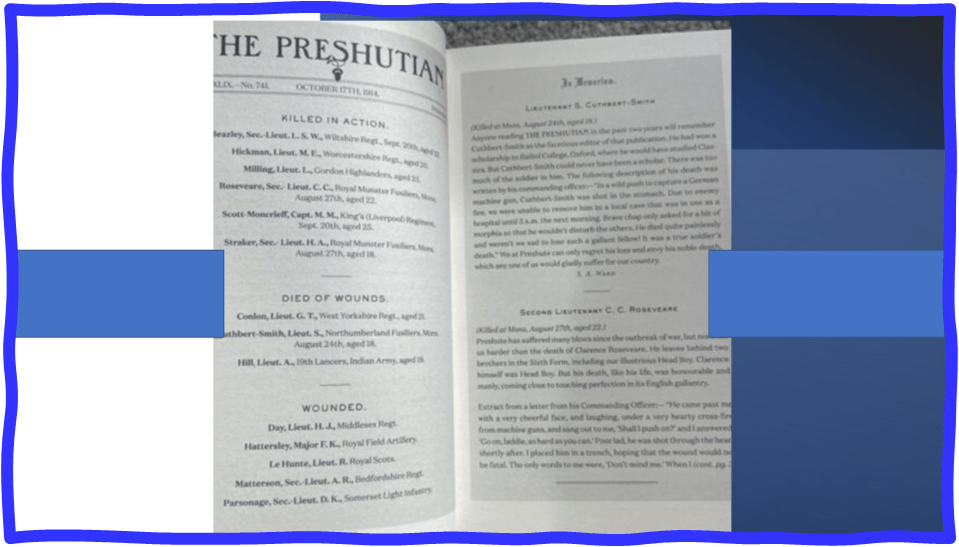

It’s not the first time Tennyson’s Maud has been used by the two men to discuss their sexual longing. On a walk outside the range if not the sound of gunfire, they use talk of that poem to initiate a passage of behaviours that lead to oral sex, that never stops either being a set of accusations between the men about the boys in their school past and the kind of commitment, or not, to liking or loving or just seeking pleasure. It is in this passage of talk that Henry says of Maud, that ‘my sister is named after that poem’.[22] Hence, it is hardly innocent that Ellwood invokes the name ‘Maud’ in relation to versifying the act of ‘fucking’ Gaunt, for on Gaunt’s death, he is promised as it were to that version of the Gaunts. Ellwood will indeed propose to Maud Gaunt after the supposed death of Henry.[23] It is a crueller joke than we can realise in relation to Henry, diminishing him in ways that must and do hurt – hence the pained uncontrollable laughter I think, and the failure of the men to go to bed with each other, with instead Ellwood ‘pretending to sleep’ whilst ‘Gaunt began to drink’.[24] Win has registered her interest in the ways adult upper class boys became men from the past of her own (and Siegfried Sassoon’s) once all-male, school Marlborough. She uses Marlborough’s school newspaper, that she mimics, and has printed in similar format and fonts, as The Preshutian in the novel to show how boys who were ‘funny’ but also ‘smug, naïve, entitled’ because they thought they would ‘inherit the world’ become matured not only by war but also encroaching social changes brought with it.[25]

Winn has also attributed the impact of the novel on her own early to motivation to write it from other In Memoriams than Tennyson’s alone for Arthur Hallam. She writes of the Marlborough College magazine notices of death on which her The Preshutian was based, that they were: ‘Heartbroken obituaries written by teenagers about their friends, each one trying to make sense of something senseless. And then the obituaries of the obituary-writers, shortly after”.[26] What strikes me here is the open-endedness, to my mind at least, pf the author’s almost fixated concentration on an act of ‘trying to make sense of something senseless’. It is this which makes her interest feel too her the equivalent of Greek tragedy.

However, I said earlier that we ‘need to return to the exploration of masculinity in war (), for that is my main theme in this blog’. And it strikes me that I have yet to consider the quotation I chose to front this blog: ‘‘Men spawled over each other. In the hypermasculine atmosphere of war, they were not overly concerned with manliness’. This brief quotation comes from a moment when, in a crowded troop train, Ellwood has allowed his sleepy head to fall on Gaunt’s shoulder. It is only when he comes to the conclusion that is stated in the above quotation, for this idea seems to spring from his point of view, that Henry Gaunt relaxes from the bodily stiffness (of resistance) that this contact prompted in him. The phraseology of this thought seems vital to me: a concern ‘with manliness’ is here relaxed precisely because the context is ‘hypermasculine’. This ought to be a paradox but yet we understand it in ways Gaunt cannot understand even his own thought yet. Hence he soon relapses into the heteronormative:

If Ellwood were a girl, he might have held his hand, kissed his temples. He might have bought a ring and tied their lives together.

But Ellwood was Ellwood, and Gaunt had to be satisfied with the weight of his head on his shoulder. [27]

Am I alone in finding this beautifully queer for norms of grammar are twisted here by desire, though he imagines a scenario wherein Ellwood is a girl, the hand, and the temples, that he imagines touching with his own body are ‘his’ not hers. Here pronouns matter immensely in conveying that that this desire is only provisional around fantasying a boy as a girl and likewise provisional in the cliched nature of how desire might be fulfilled. That is because, I think, the undercurrent of this scenario is that the hypermasculine has become a place of felt and expressed passion, for which a boy’s past and ideological preparation has no model. It is as if sex/gender were becoming irrelevant in the pressure of a love engendered by choices within one’s circumstances. There is no ideal object of the masculine – at least not one that need be rigidly gendered. The passage leads to the young men sharing a bed and to a ’kiss’ simplified out of individual pronouns in a communal ‘Their’: ‘Their lips met, and things became simple’.[28]

Of course I may be over-reading – making too much of a few pronouns but queer love hyper-realises sexed/gendered pronouns, love tends however to be simply non-binary. If I had to say what this novel feels to me to be about, it is the realisation that no binary is sufficient and always inadequate. For decades novels of romantic love have valorised the binary descriptions hard and soft as if they were equivalents of the binary man and woman. When he loses Ellwood, Gaunt remembers him by this binary as he tries to kiss a woman, Elisabeth the German librarian in his prison camp: ‘She was soft where Ellwood was hard, …’.[29] But this is not the Ellwood he has ever wanted, this man who is ‘hard’. Early in the novel, when the pair travel to Munich before the war is thought of: ‘Gaunt had once pressed himself against Ellwood’s leg and discovered that Ellwood was hard’. This transformation of boy into hard phallus is not what Gaunt wants, which he likens to ‘a cold fumble in a Bavarian field’, but what Gaunt wants is someone softer – where the kind of loving is not polarised into male biology. For he wants Ellwood not just to be the memory of a hard cock but to someone who might ‘feel something for once. Gaunt was sick of feeling things’. Sick, of course, by feeling things in a manner that is unreturned; because men have not reached that hypermasculinity where they forget their ‘manliness’ in favour of mutual love. Even Elisabeth was better at this.

I know I read this book very subjectively. But allow me. You will enjoy it (I am sure) for your own reasons. And how do I feel about a heterosexually self-defining woman writing about and helping to shape gay male sexuality. Fabulous really! For we get trapped by sex/gender definitions too easily into shallowness in our loving desires.

Love & best wishes

Steve

[1]Alice Winn (2023: 120) In Memoriam Viking (Penguin Random House)..

[2] Hephzibah Anderson (2023) ‘In Memoriam by Alice Winn review – a vivid rendering of love and frontline brutality in the first world war’ in The Guardian online (Sun 12 Mar 2023 11.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/mar/12/in-memoriam-by-alice-winn-review-a-vivid-rendering-of-love-and-frontline-brutality-in-the-first-world-war

[3] Alice Winn cited by Mark Skinner(2023) ‘On the Background to In Memoriam’ A Waterstones blog available at: https://www.waterstones.com/blog/alice-winn-on-the-background-to-in-memoriam

[4] Alice Winn op.cit: 43

[5] Ibid: 102f. & 109f. respectively

[6] Ibid: 144

[7] Ibid: 359

[8] Hephzibah Anderson op.cit.

[9] The Preshutian ‘Roll of Honour’ in Alice Winn op.cit: 159f, the Tennyson poem ibid: 161f.

[10] Alice Winn op.cit: 19.

[11] Ibid: 82.

[12] Ibid: 344

[13] ibid: 28f.

[14] Ibid: 301

[15] Ibid: 57

[16] Ibid: 314f.

[17] In Mark Skinner, op.cit.

[18] Ibid: 121

[19] Ibid: 114

[20] Ibid: 10

[21] Ibid: 134

[22] Ibid: 100 – 103

[23] Ibid: 314

[24] Ibid: 134

[25] Mark Skinner, op.cit.

[26] Ibid.

[27]Alice Winn op.cit: 120f.

[28] Ibid; 122

[29] Ibid: 236

Fascinating!

LikeLike