‘He had a sudden strong desire to tell his story to someone, as long as it was to someone without ears. … Billy and June would have different versions. They were sort of uncompleted chapters, and even when he put them together in his own mind it was hard to find where they joined. Even to believe half of it. But he was obliged to believe it. Because in the first instance a witness should be believed. … He felt he should believe – believe himself’.[1] Stories are not evidence of the truth, are they? But if they aren’t why do we need them? This blog is on Sebastian Barry (2023) Old God’s Time London, Faber & Faber Limited.

The British and America covers: Barry in the hold of Gothic religion.

Sebastian Barry is a novelist I have followed with delight, and some sharing of the pain he exposes in his novels and poetry since I read A Long Long Way after it first came out in 2005, mainly because of its championing by J.M. Coetzee, a novelist somewhat similar in these respects. The pain I speak of seems always to have an obscure (and sometimes deliberately – and perhaps necessarily – obscured) link to his family and personal history but it is also one which can be generalised beyond the stories that helped construct the persona we know as that of Sebastian Barry. Some of the pain can be generalised certainly to the experience of growing up in the Irish Republic (with a family split between Protestant and Catholic roots) after Independence but it also speaks to much more. On the discovery, for instance, of the fact of his son’s life as a queer boy and man growing up in Ireland and experiencing the United States, he absorbed and generalised those stories too in novels – to his wider family history, to the issues of Irish emigration to the United States, and to contemporary debates on queer politics. I have touched on this in an earlier blog about his 2020 novel A Thousand Moons.

In Old God’s Time, Barry returns to childhood in ways which might reflect himself and might not. The fact that a family name, McNulty (which has oft been explored in earlier novels), is used may shed an obscure clue To Barry’s intention but does not justify autobiographical application, particularly since it is given to a woman who, like Barry’s mother, who has played at the Abbey Theatre and has a somewhat shadowy son, who is perpetually on the verge of being seen properly and definitively (or is he?) by the narrator-hero, Tom Kettle. But Tom is as near to the concept of the unreliable narrator as any narrator of any novel gets and much of what is said in this book on the issue of childhood is too widely generalisable, even if this child is one who is extremely vulnerable, to be a pen-portrait of the author alone,if at all. In 2017, actually being interviewed about Days Without End (2016), the novel preceding its sequel, A Thousand Moons, he was clearly caught by the interviewer in a moment revelatory of precisely the feelings about him as a novelist I describe above. The interviewer quoted here is Stephen Moss in The Guardian.

Barry has described his childhood as a “singular mess”. He says he and his three siblings were farmed out to relatives, which is how Barry heard the stories about the first world war, the Easter Rising and the civil war in Ireland that he has used to such effect in his novels. This obsessive winnowing of family secrets suggests a search for certainty after a childhood that had little.

“When we were children we did feel a little bit up in the wind,” he says. “My mother was an actress, my father was a drinking man, and we weren’t totally safe as kids.” He has previously hinted at a darkness in his childhood – …. He will not, however, be drawn on the precise circumstances of what he once called “the thing that hurt me into trying to put something back in its place. To set up a thousand kingdoms to heal that one blasted site that has nothing on it.”

That sentence is Barry at his most lyrical and plangent, but I take it to mean that the neglect (and perhaps worse) he experienced as a child led him to explore his wider family and pushed him towards the fantasy life that feeds the novelist.”[2]

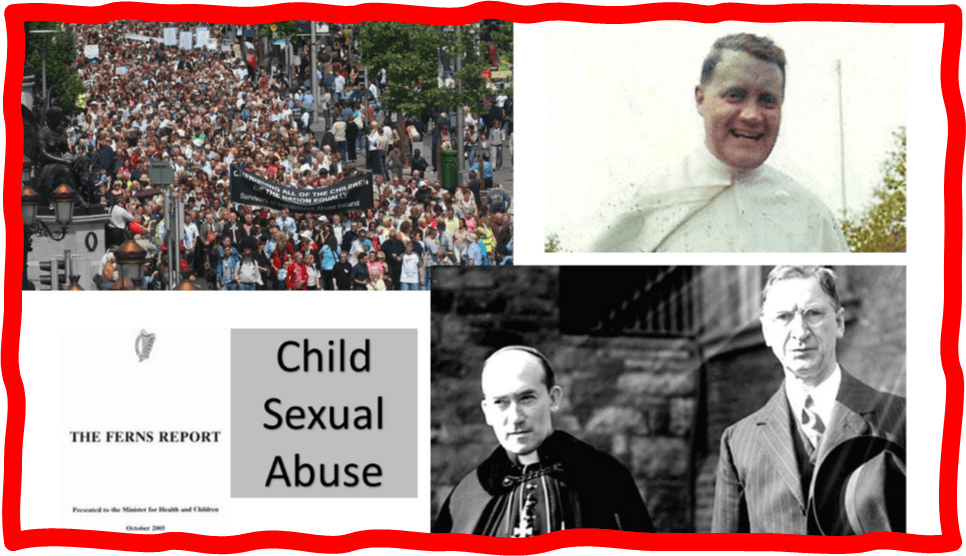

In retrospect, this prefigures much that is illuminating about Old God’s Time, which focuses precisely on disrupted, unsafe childhoods and crimes against the child, often horribly greater crimes than ‘neglect’. Indeed the latter aspect of the novel reflects on the experience in Ireland of child sexual and physical abuse revealed publicly in The Ferns Report (2005); about which Colm Tóibín has a fine contemporary essay reprinted in his 2022 book of essays A Guest At The Feast (the link is to my blog on the book). Considering this theme in the novel, Melissa Harrison in her Guardian review of Old God’s Time says that ‘it is not the only work of Irish literature to grapple with that grim legacy, but it may prove to be the most powerful’.[3] This is true to my experience. The theme is treated from a greater distance by John Banville in Snow and April in Spain (the links are to my blogs); if less so but still with a distance provided by the genre of writing than his Benjamin Black novels (Black is Banville’s nom de plume as a crime writer – although he appears to have abandoned it lately). However, Barry may have felt that influence from Banville / Black enough to also mediate his themes of childhood vulnerability through the mind of a police detective or detective’s ally; and for the same reasons as Banville perhaps. I take that reason to be the way something hard to think and feel about rationally is explored through a sense of an unknown that must be penetrated by a process of interviews in which probing questions receive answers that might either reveal the truth or may further obscure it or. perhaps, do both simultaneously.

When truth has been long hidden (even covered up), as is the case in many examples of widespread child abuse, then we are fighting the forces of repressive as well as oppressive male power to keep it so; even sometimes with the undesired but nevertheless ‘collusive’ fear of exposure in its victims. An essay I found illuminating to think about in relation to this novel is the written version of the third of three lectures Barry gave in 2021, ‘The Fog of Family’ in The Lives of Saints published in 2022. Fog is, after all a ubiquitous phenomenon in Old God’s Time, whether it be the fog that swirls the Irish coast at Dublin Bay or the fog in the coming and going of the apparently lucid in Tom Kettle’s thinking and feeling:

David Costello ‘Fog rolls into Dublin Bay’ available at: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/567664728028897151/

The usual fog cleared a moment from his mind. …The fog edged away from the shore of himself, the sea opened like the stage in a theatre, the helpful sun burned in its element, there was a truth told to him, a truth in his curious age, in his palpable decay, …[4]

And at the centre of that fog – in an omitted section of my citation of it – are dream-like fantasies about the lives and purposes of once living ‘detectives’. In ‘The Fog of Family’, Barry equates the milieu of ‘painters, poets and mad persons’ who built his own father’s consciousness of the world whilst living in Hampstead in London with: ‘A fogbound coast of a generation’. For such men, mired in existentialism, ‘family and history were dead, …, and love too’. His pity for them is balanced against ‘woe to’ those people like himself that were the ’child of such people’.[5] It’s clear, isn’t it, that this does suggests a cognitive and emotional association to the experience of Tom Kettle but also suggests that this may be the condition of the twenty-first century writer, emerging from the uncertainties of twentieth-century forebears. The lecture ends with Barry saying that to be a writer requires that the person thus initiated needs to deal with ‘things that even clear vision can’t unravel. Nothing can be done with the truth maybe’. And that is because:

Fiction likes the fog more than anything, it seems to me, out of which faces emerge, suddenly. Perhaps real truth comes through the battered eyes of fiction. The fog is ultimately beneficial, beneficent, actually illuminating with its darkness and erasures. It is the distillation, the subtle whiskey of truth.[6]

Now the effects on consciousness of whiskey (often through a denial of their relevance as in most alcohol afficionados whilst in its denied grip) is often brain fog and illusory vision (in possible dementia for instance). All of these are potentials behind the tissues of truth and lies of this novel, and not only from its many whisky drinkers. As nearly every review, though I use Declan Ryan’s review in The Observer here, says (stating the obvious though) Tom Kettle is ‘an even more unreliable narrator than Roseanne McNulty was in The Secret Scripture’ and that the novel hence reproduces ‘the backtracking of false testimony, feeding the reader dead-end leads and disinformation’. Strangely, however, Ryan is also not alone in not liking this novel’s ‘dreamlike logic’, saying it ‘can frustrate and deliberately confuse because more than one descriptive passage is undermined by Kettle waking from sleep. The facts, too, become increasingly hazy, allowing for suggestive, symbolic imagery’.[7] However, it is one thing to be confused, another to show that you are entirely antipathetic to the novel which asks questions, whose answers can never be stated because as a better critic, Susie Boyt in The Financial Times, says:

Barry situates ambiguity squarely as the novel’s subject, its heart, perhaps its hero. … he gives us prose so completely suffused with the outlook and professional rhythms of his protagonist that the sentences land like an extension of Kettle’s central nervous system. / … In Old God’s Time the realms of dream and apparition and conjecture are as sharp as anything factual, perhaps sharper in their essence, because they are more strongly felt, more forcibly required.[8]

Novels deal with stories that inevitably test the credibility of their listeners. Indeed, if they did not, they would not be readable as novels, for they explore those things about our social and individual beliefs and the rest of our psychological apparatus that does not yield to merely straightforward ‘logical’ analysis or other conventional norms of thought, without missing out too much of how people act in real situations. Hence even a detective will be stymied in looking for answers to some questions of the motivations that guide human actors. In ‘The Fog Of Family’ Barry says that:

Not asking is a feature of much lost history, … Time itself asks no questions, it marches bluntly, mutely, on. Perhaps it has no questions, or none worth asking, or none anyone or anything would know the answers to.

Young men, he goes on to say later, don’t have any way of asking questions of the process of aging, and mutability because they are too full of ‘the confusions of youth that feel like certainties. I had no idea it would be my life’s work to dig into ( ) secrets, those things unknown, half seen’.[9] By youth, he means that terrible age filled up by the immature ego rather than childhood per se. Youthful narcissism must be abandoned, or penetrated beyond, if a novelist is to reach the ‘foggy heart’ of an observing child:

What are writers made of? Imponderable ocean-deep flotsam and wreckage. A jam-jar of fog. A bell jar needed to glimpse anything. A shaken hear. A shocked face. A deviated septum. Out of these things we write, or try to write. …..[10]

In the end, the attitude of a detective is insufficient for a novelist or their narrator to uncover the truth of things, I think. That is because that attitude is too like that of the raw youth, who thinks that they just need to know more in order to understand, or witness to, truth. Indeed, the evidence may lead to the discovery that one is not just a victim, or even a neutral witness to disruptive and unsettling life events but rather a suspect likely to have done or to do now or in the future the same crime of negligence and refusal to safeguard that which we value. And this is Tom’s position. Poised between being asked to witness to things that might solve a crime, even a ‘cold case’, and being a suspect for that crime; an exemplar of just another predatory male. The chances are one might be as neglectful as those who reared you, as Tom thinks when he recalls that once he had ‘struck the boy’, his son Joe, ‘a blow that cost him a quarter of his soul’s worth’, just as he had once ‘been struck’ in his ‘dread exile, nuns and priests and Brothers’.[11]

The crime the novel posits for Tom would be that of him being responsible for killing a priest, even if the ‘evidence’ that would be assembled would be ‘inadmissible’, and in Tom at least linked to retributive shape-shifting fantasies wherein he, in memory, becomes one with his wife, June. In scenes of shapeshifting brilliance whilst he becomes a wolf, she becomes a rat: both transformed to be ‘like wolves, like hares, like jays, like any animals not wishing to be seen, abhorring the company of men’.[12] And the suspicion that even the good and worthy share the guilt of the condemned or damnable applies too to even to the worst crimes of the Catholic Church in Ireland and specifically in Dublin in relation to this novel. This seems to me the inevitable conclusion, for all the horror rightly evoked by the actively guilty iondividuals ion this novel. The latter are Fathers Byrne and Matthews (fictional beings but easily equated to real priests like Brendan Smyth) and the very real Archbishop McQuaid (mentioned so often in the novel – named the ‘king of this fuck-up’ by the young detective O’Casey at one point) who as co-authority political and religious with Eamonn de Valera colluded with the events; and may even have been more complicit than that in some accounts. To this Tom Kettle refers in God’s Old Time when he speaks of:

All the children gravely assailed. All the children in filthy Irish history, with no bugle blowing to announce their rescue, no arms of love to envelop them, no hand of kindness to wash their wounds.[13]

Child Abuse Reparations Protest in Dublin from The Times at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/millions-still-outstanding-in-child-abuse-reparations-zvh3976zt?region=global; Kilbarry1 (13 Feb. 2020) John Charles McQuaid and Eamon de Valera, December 1940 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:McQuaid_de_Valera.jpg; Illumina29 Father Brendan Smyth. This version was cleaned up from stains by uploader. – Illumina29’s own photograph, a bit damaged from a recent flood. He took this photo when he was about 9 years old, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125044

I think that, however, we cannot see this as Barry’s ‘Irish child sex abuse novel’, even if such a genre could be claimed to exist, for at its heart are much more fundamental relationships between paternal authority, love and children and particularly in the transitional passage of that authority between fathers and sons. That relationship is oft caught in the moment of its disruption, as in the case of Joe, Tom’s queer son. This mirrors the fact that Barry’s first son, Merlin, taught his father all he didn’t know before about the range of ways in which this world is queer and why trying to understand it through hegemonic norms alone always fails, at least in part. The sins of the Holy Fathers of the Irish Catholic Church in its unhealthy alliance with the early Irish free state are indeed great in this novel and the realities of Irish history it points towards. The sins, too, of the fictional McNulty father figure have that same function, told with the gusto of a melodramatic thriller with dark themes regarding child safety, as we shall see. I have no doubt that one central message of the novel is to bear witness to the duty we all have, as human beings, to safeguard children and childhood. It is suggested in ‘The Fog of Family’ in 2022, using examples from his own family, that this duty is the duty taken on by himself and his wife Ali to reconstruct family as a principle of protection: ‘Out task was to protect it, to let our children feel the bounty of safety, and that’s what we did’.[14]

God’s Old Time makes obvious reference to the duty of a nation state to children irrespective of their biological parentage. For instance, Tom Kettle has been the object of discriminatory practice because of his ‘wretched background’: ‘Orphans were held in low regard. Not that he was an orphan, but he was tarred with same brush’.[15] To further emphasise child safety as a theme, this passage is made proximate to Tom narrating a visit to the Turret Flat next to his, in which live Miss McNulty, a former actress who trod the board of the Abbey Theatre (as did Barry’s own mother) and her ghost-like son.[16] Miss McNulty at this point recounts her suspicions of the anal rape (and death therefrom) of her daughter by her husband and the children’s father. From this belief she fears for the safety of her boy child. Miss McNulty has no proof of her beliefs though she has fled her husband, about whom she says: ‘…, he could even be innocent in some way I can’t imagine, but, I don’t think he is, that’s my feeling, but why didn’t child protection services protect us, protect my little girl, who’s dead’.[17] The story strikes a reader as extreme to the point of being incredible (though such crimes do actually happen despite our reluctance to believe this as any social worker will tell you – indeed as I can tell you were not the detail of all that horror confidential).

In another example, Tom, in recounting how he and wife June compensated for their own wretched childhoods in the care of a violently uncaring Church, makes a principle of how they both ensured, or tried to ensure at least, that their children (Winnie and Joe) were, at the least, ‘both seemingly happy kids’, though the word ‘seemingly’ sheds doubt over the subject. Nevertheless their view is stated clearly as a kind of banner heading for the theme of which I speak here: ‘Their victory! Safety, the sanctuary of a decent childhood’.[18]

Indeed so fundamental is the principle of children as the rationale of family that the novel includes the fact that this is named as one of the many failings of Archbishop McQuaid to report to Rome the failings of his priests, as required, since it was a crimen pessimum [an example of ‘the foulest crime’].[19] Failed by the Church, Tom becomes in his own mind the avenger of this crime in relation to Miss McNulty’s son:

To threaten a child, to bring hurt to a child, was the chief crime before God and man. It must never go unpunished. A Child was a small matter by definition. Who will speak for the child? Who will act for him or her? It seemed to Tom, in the great dark of human affairs, that he could say he would. And he had done so.[20]

Perhaps, since Barry knows ecumenical history well, Tom and June also implicitly correct the Church in its own application of ideas of what constitutes a crimen pessimum, which we now know was applied by the Vatican in 1972 to sexual behaviour directed at a man or men by one of its priests, as in the following: ‘The term crimen pessimum [“the foulest crime”] is here understood to mean any external obscene act, gravely sinful, perpetrated or attempted by a cleric in any way whatsoever with a person of his own sex’.[21] In contrast to this secreted principle locked in the Curia’s archive are the homely reflections of Tom and June when they compared the secreted paedophile activities of priests to their new knowledge that their son Joe is gay. What it embeds is something so essential to the ethical heart of Tom’s and June’s lives, that one should through time learn how to change and embrace differences to both one’s habituated norms of belief and conventions – notably that which is deemed queer to normative experience.

Although it wasn’t a girl (Joe) wanted to fall in love with but a boy, as Tom well knew, though that wasn’t something he could talk about it as well as he should have been able. “There’s no harm in it,” said June. “It’s just the same as Winnie liking a man, it’s exactly the same.” It didn’t seem the same to Tom but he was understanding it all better as time went on, till time was taken from him. There was no point thinking of the Brother that used him as a little boy, because it just wasn’t the same. June said it wasn’t the same.[22]

I find this beautiful as an imagined narrative of coming to terms with the knowledge of a son who did not follow the expected norms of an older man’s life but also with the hope that the darkness of ignorance will turn into light. For light separates the corrupt power of rape from new potentials in loving. My best friend, Justin, has often said to me words that suggest there is no such thing as a lapsed Catholic but only a Catholic who tries to reinvent the belief in love of human beings for each other’s good and the formal beauty of that aim that Catholicism enshrines.

However, we should press on because it is precisely to avoid reducing this book to message, even about the sanctity of the duty of child-care; especially the kind of care that opens a child to be able to discover and explore non-threatening and often shared novelties in life like a non-normative love-choice. What I want to return to is Barry’s obscure (in every sense but not negatively) suggestions in ‘The Fog of Family’ that: ‘Fiction likes fog more than anything …’. And in this liking the fiction-writer goes ‘on writing only realising little by little that [the author can] know nothing’ about the past he thought he knew.

Out of the obscurest of subjects (even from the moment Edmund Spenser desired to wite a long work that was a ‘dark conceit’) writing comes to have wider aspirations than simple truth-telling. As Barry puts it, in continuing in the same lecture: ‘Perhaps to have known everything, in those early years, to have seen everything, would have meant I could never be a writer’.[23] What makes book what it is then is often a metawriting (writing about the nature of writing). But it is also about meta-reading (reading about the nature of reading) because both reading and the writing are required and essential for a truly communicating art (in any medium). And this is a novel about a reader of written and other art across many genres and modes (film, fiction, history etc reader of children’s fiction, consumer of the Bible and Roman Catholic liturgy). There is a piece to write about films, which would improve on Declan Ryan’s perception (true in ways he does not know how to use as a reader prepared to learn from, rather than judge, writing) that ‘Old God’s Time has something in common with the western, …’.[24] For the rough justice Western is not the only Hollywood genre referenced.

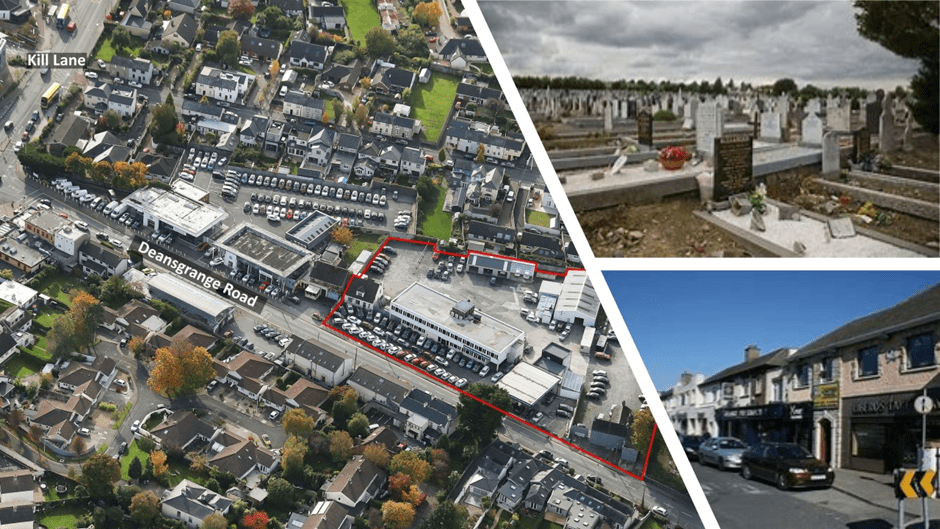

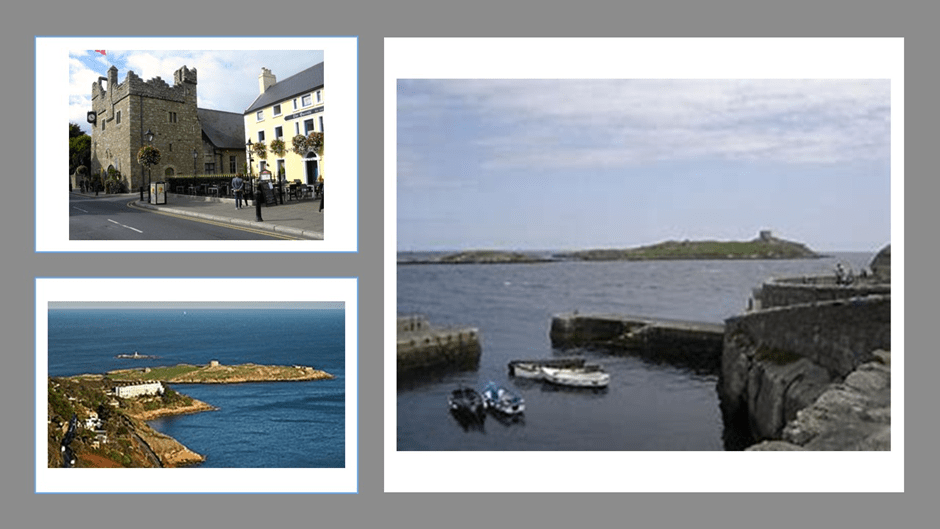

When we are first introduced to Tom Kettle, it is through the books he once read, stored still in the box in which there put during his move from the suburb of Deansgrange to Dalkey Island in Dublin Bay. These books are not unpacked from that box till the end of his story as we read it.

The books remembering, if sometimes these days he did not, his old interest. The history of Palestine, of Malaya, old Irish legends, discarded gods, a dozen random matters that at one time or another he had stuck his inquisitive nose into.[25]

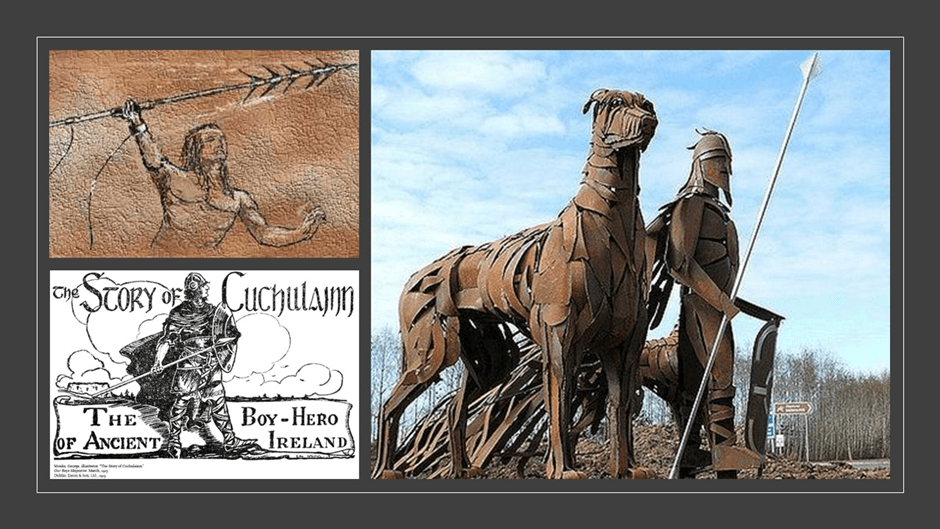

That books store memories seems an obviousness that critics often miss. For instance, Jude Cook writing in Literary Review says Old God’s Time is a book full ‘flights of memory and his [Barry’s] excavations of his deep past’, but in a sense, isn’t that what the first page excursion on Tom as a reader of books is about. Books store more than the memories put into them by the writer as material for their writing, they store the memories of their contextual reading: ‘his time in Malaya as a sniper, his years with the Garda’.[26] The reading context of these books mixes the history of personal or autobiographical timeline with the histories of those cultures that is the subject of the books. I think they point to those events of Palestine recorded in the lives of Christ and his Apostles, and their Apostolic Churches, and to stories of legendary gods discarded in the process of Christianization, including demi-god heroes like Cúchulainn who appears in the memories and metaphors of the novel to deepen themes of the meaning of youth and the tragic loss of sons. It includes too Gods of Greece and Rome, as well as the God from whose worship at the novel’s current moment, Ireland is moving.

Let’s take Cúchulainn’s appearance in the novel however, shadowed even by the memories of Yeats in Miss McNulty’s experience in the Abbey Theatre (as it was for Barry’s mother he tells in The Lives of The Saints) in whose plays Cúchulainn matters as a symbol of renascent Republican Ireland (Ulster myth though he be – ironically now given Ulster’s wayward follow-up history).[27] It is not only possibly innocent references like that, for instance, to local Dublin ‘boys from the little streets’ warding off unwanted gazes by the supposed superior as ‘Unlettered Cúchulainns’.[28]

There is a more resonant use of Cúchulainn’s story. Tom is at this point reflecting on his lonely life at Dalkey and remembers the role he had imagined himself to have in his marriage with June. In this instance, the imagery of the hero as ‘Hound of Ulster’[29] is employed:

In the bed that night that he always thought of as her bed. Her place of safety in the dark night. Where he was her watch-dog, her Cúchulainn. … The children in their childhood beds. Her in the summer-cold graveyard. Her remains in the execrable coffin.[30]

This employs so much a non-Irish reader may lose, for the pagan hero’s fabled faith to his own people is matched by stories of tragic loss, including the killing of his son due to misrecognition, which richly contextualises Tom’s shift of consciousness from his living wife to her now being long dead, and the barely unacknowledged yet in the novel of the similar fate of both of his children.

But other myths arise from reading too in the novel. In particular it deals with Tom reading out to his own children of young people’s books (or books used for children like Oliver Twist). They include Treasure Island, which appears in reading contexts that associate it with responses to aging and the aged in children in children and parents: Winnie, for instance, refuses to allow it to be read to her when the narrator passes from a child to a man.[31] Dracula is made to represent an emblem of life-in-death and death-in-life as Tom sleeps, whilst the film Nosferatu is used to indicate the liminal appearances of scenes in the metamorphosis caused by both weather conditions and dreams.[32]

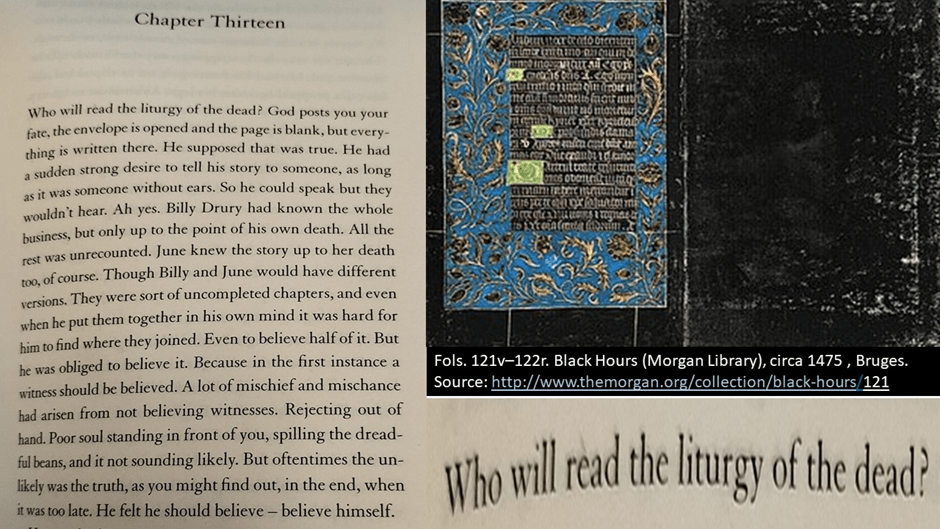

This was also the method of Barry’s very early boy’s story Elsewhere: The Adventures of Belemus (1985), wherein the fantastic orchestrates the life of a boy otherwise disengaged from his home and school life, and even his friends (as Barry sometimes suggests was he too as a boy). In Old God’s Time, references to legends, books and film memories encountered are almost religiously (or more literally ritually), interspersed if also with some of the uproarious humour of the earlier book in some of the ritual passages. They perform as touchstones for contextual memories not of the book as an object but as a read (or reading) experience. The best metaphor for them is the book’s own, that they perform an almost liturgical function, analogous to a codex of liturgy such as that of the Catholic Church, that Tom names ‘sad stations of memory’, in reference to the Stations of the Cross.[33] In part this is because amongst the written books referenced in this book are books of liturgy, almost more prominent, than scripture – although claimed by the Catholic Church to be of equal authority for representing the Body of Christ, in that way that that individual body is often metamorphosised into the social body of the Church of God’s community.

Liturgical books authorise the proper actions of the body of the Church and the body of priest and congregation officiating in them. They validate its holiness in the eyes of the church they serve. Hear this from Adrian Fortescue’s summary of Catholic authority:

Liturgical Books. —Under this name we understand all the books, published by the authority of any church, that contain the text and directions for her official (liturgical) services. It is now the book that forms the standard by which one has to judge whether a certain service or prayer or ceremony is official and liturgical or not. Those things are liturgical, and those only, that are contained in one of the liturgical books. It is also obvious that any church or religion or sect; is responsible for the things contained in its liturgical books in quite another sense than for the contents of some private book of devotion, which she at most only allows and tolerates. The only just way of judging of the services, the tone, and the ethos of a religious body, is to consult its liturgical books. Sects that have no such official books are from that very fact exposed to all manner of vagaries in their devotion, just as the absence of an official creed leads to all manner of vagueness in their belief. In this article the liturgical books of the Roman Rite are described first, then a short account is given of those of the other rites.[34]

What prompted me to find out about this tie between books assumed to have canonical authority and ritual action was the way in which Old God’s Time has a kind of ritual reference throughout, though not necessarily a Christian one, and if so one heavily compromised with pagan legend. For instance, when Tom conflates his memory of his late wife’s bed with her grave that I refer to above, his mind ranges from bedroom to kitchen in his present home, focusing on the bread knife that he either remembers or fantasises as the weapon used to murder his wife’s priestly rapist, Father Thaddeus Matthews:

on the breadboard, chill and dark, the sacred bread knife. Which in killing had not killed. In exacting punishment had not punished. In seeking to be the instrument of redemption had not redeemed.[35]

Even the rhythms of this prose are the rhythms of Catholic liturgy. They demand to be read, in the sense of ritually read aloud (and indeed hearing Barry read out his own work has a kind of priestly authority – I once said to him after an event and at the book signing that it was like being privileged enough to hear Charles Dickens read his own work in public). And there is a similar sense of ritual sacrifice involved, a similar priestly function. The fact that liturgy in Catholicism is solely that which priest perform, and priests alone apart from the scripted responsories, resonates with that idea of the writer as liturgical instrument.

Indeed, I felt I needed to work this out before I felt satisfied with the tremendous opening of Chapter 13: ‘Who will read the liturgy of the dead …’. I thought this because the opening puts such stress on the potential of the absence of priests, ruined by their own sins in the life of June and Tom, but whose role of authorising a way out of Purgatory still exists, even if symbolic and psychological a Purgatory in which memory is roasted, like the Welsh rabbit in Tom’s unholy grill. That cavern is like ‘a damp, evil grotto’ whose ultimate cause ‘lack of oven cleaning’ is described as ‘one of those original sins that bothered him’.[36] We can leave the Inferno like Dante or be draw back to it, as a visit from detectives from his old Garda station ‘drew him right back to his own early days policing’.[37] Chapter 13 concerns those rites (‘the liturgy of the dead’) due to the dead wives, sons and daughters and owed by oneself whilst living, or one’s loved ones when dead:

This is why I cite this chapter in my title. I find it central for it concerns the absent reader, a priest like officiator over the meaning of things lost to memory (like the dead might become), hard to regain or redeem, and for whom, without a living ritual religion, one has no framework for thinking about. I give most of the page above because It is too rich to quote briefly, which one still must do.

Who will read the liturgy of the dead? God posts you your fate, the envelopes is opened and the page is blank, but everything is written there. He supposed that was true. He had a sudden strong desire to tell his story to someone, as long as it was to someone without ears. … Billy Drury would have known the whole business, but only up to the point of his own death. All the rest was unrecounted. June knew the story up to her death too, of course. Though Billy and June would have different versions. They were sort of uncompleted chapters, and even when he put them together in his own mind it was hard to find where they joined. Even to believe half of it. But he was obliged to believe it. Because in the first instance a witness should be believed. … He felt he should believe – believe himself’.[38]

The whole of this passage spins on the difference between a canonical book authorised (indeed authored) by God and any other sort of book, like the long produce of the modernist revolution (and the incompleteness and relativity it spawned). That is because modernist relativism is not a problem that is solved (for after all postmodernism is merely an untortured acceptance of what to modernism is a dilemma) but a current reality. We are now in a relativist world wherein there are no priests left worthy to ‘read the liturgy of the dead’ or insist that the blank page of God is filled with the meanings insisted upon by His Church. And we have to accept that. Hence even Tom’s suicide attempt is a comic moment (‘wandering foolishly about the flat trying to find something to tie the rope to’), based on the fact that ‘your faith in human nature is in the ground’ these days.[39]

Before we leave this passage from Chapter 13, we have to notice that it is about the nature of witness – a solemn task given to both priests and believers in and by the Church of God that Tom continually confutes with modern witness statements. Indeed he will find that to be a witness is not that far from being a person witnessed against as he is by Father Byrne in the novel, in the matter of Father Matthew’s death. Tom has witnessed to the whole earth as Acts 1: 8 instructs Apostles of the Church (From Malaya to Dalkey is a larger geographical span than the Biblical text after all) but he is not only a ‘false narrator’ (as the reviews I have cited thus far tell us) but a false witness, a disguised perpetrator of crime or something that can be conceived of as such. There is no certainty in Tom’s view that ‘a witness should be believed’ in Chapter 13’s opening.

If the difference between death and life is reduced by the failure of any WITNESS to the truths that differentiate them other than as differing states of matter, then the mental geography of this novel becomes much clearer. For to be living is merely to be noticed and/or remembered and that is why there are so many ghosts in Tom’s life, ones like Mrs Tomelty for instance, that he convinces us in his early narrative still exists but which we and Tom find to have died in 1988 when we are near the end of the novel.[40]

The issue is even more puzzling with Tom’s whole family for we are told wife, daughter and son are dead before we read of daughter Winnie’s arrival at Tom’s door. The storytelling sets out to reproduce contrary beliefs about Winnie, that focus on the space she hold in Tom’s memory reduced to the geography of Dublin – to the transitional suburb (really a crossroads apart from a huge cemetery, of Deansgrange where the family once lived when Tom was a detective: ‘their old place in Deansgrange, near the famous graveyard’.[41]

How should we then read the conversation recorded as if witnessed between Winnie and Tom.

He knew where she was living but where was it? It had just slipped his mind. He was growing demented, he must be. “Where are you living?” he said, in some distress now, a bit of a headache brewing.

“Deansgrange, Daddy, Deansgrange.”

“ But we’ve left Deansgrange,” he said again with the note of panic and misery in his voice.

“Well, but I’m still there, Daddy.”

“Not the cemetery!” he said, with a small cry.

“Yes, Daddy, the cemetery”.[42]

It is thought the most distressing of symptoms of dementia, if this is in fact witness to this is the dual consciousness that defensive confabulation to cover over gaps in memory (sometimes to the point of hallucinatory experience, is indeed the very illusion from which one is trying to defend oneself from believing it so to be. If so, this is so painful, yet the passage can equally be read as a kind of Pinteresque romp, a kind of acknowledgement of the lack of any mutual understanding in even close encounters and conversational exchanges – an emptying of meaning from all human congress.

This is a wonderful novel. This so even though it is also probably true, as Jude Cook says, that it is writing that ‘might have been saccharine or melodramatic in other hands’. Particularly this is so when the novel explores the fact that ‘neutrinos’ or ‘atoms’ within matter may be all there is to know about it, complex but reductive, or Tom learns about how short the life of a robin is. But I never sensed any such malaise in it, for we believe in Tom though we do not, because we do not, have to believe what he says as his story turns to Irish shapeshifting mythology, for instance. For me, it is another triumph from Sebastian Barry.

Dalkey and Dalkey Island where Tom lives.

Love & best wishes

Steve

For other blogs on Sebastian Barry, see:

[1] Sebastian Barry (2023: 191) Old God’s Time London, Faber & Faber Limited.

[2] Stephen Moss (2017) ‘ Interview: Costa winner Sebastian Barry: ‘My son instructed me in the magic of gay life’ in The Guardian [Wed 1 Feb 2017 18.54 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/feb/01/sebastian-barry-costa-book-award-2017-days-without-end-interview-gay-son

[3] Melissa Harrison (2023: 47) ‘Survivor’s song: Sebastian Barry’s sublime study of love, trauma and loss grapples with the legacy of abuse’ in The Guardian (Sat. 25th Feb. 2023).

[4] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 80f.

[5] Sebastian Barry (2022: 112f.) ‘The Fog of Family’ in The Lives of Saints: The Laureate Lectures London, Faber & Faber Limited, 83 – 119.

[6] Ibid: 118

[7] Declan Ryan (2023) ‘Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry review – a cop you can’t trust’ in The Observer [Mon 27 Feb 2023 09.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/27/old-gods-time-by-sebastian-barry-review-a-cop-you-cant-trust

[8] Susie Boyt (2023) ‘Old God’s Time — Sebastian Barry’s enthralling, haunting new novel’ in The Financial Times (MARCH 2, 2023) Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/6b2de4a4-d317-4d0e-a70f-0898ae1b7487

[9] Sebastian Barry 2022 op.cit: 94f.

[10] Ibid: 115

[11] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 143f.

[12] Wolf ibid: 171, rat ibid: 209. The quotation ibid: 213.

[13] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 216.

[14] Sebastian Barry 2022 op.cit: 109.

[15] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 133. The fantasy of being an orphan as a substitutive narrative to disguise the shame in one’s ‘wretched background’ is a theme in literature particularly associated with Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Barry had even referenced this myth from that source directly in his early story for young boys, Elsewhere: The Adventures of Belemus (1985, Montrath, Portlaoise, Brogreen Books, The Dolmen Press). In one episode of the Book, Belemus Duck is taken by a Beadle named Mister Creek from an orphanage to rich people who will become recognised as his parents. The hint of Oliver Twist is reinforced when we are told that the Beadle: ‘Mister Creek bumbled in the door, rattling his keys’ [page 51]. The choice of verb here, unusual in any case, is a clearer pointer to Mister Bumble the Beadle from the Dickens novel.

[16] McNulty is the name used to indicate members of one branch of Barry’s past wider family from 1998 in his wonderful saga of reborn Ireland, The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty [London, Picador].

[17] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 139

[19] Ibid: 215

[20] Ibid: 258

[21] INSTRUCTION On the Manner of Proceeding in Causes involving the Crime of Solicitation; TO BE KEPT CAREFULLY IN THE SECRET ARCHIVE OF THE CURIA FOR INTERNAL USE.. NOT TO BE PUBLISHED OR AUGMENTED WITH COMMENTARIES. The citation from Ch. 3, Title Five, paragraph 71 of Vatican document available at: https://www.vatican.va/resources/resources_crimen-sollicitationis-1962_en.html

[22] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 147

[23] Sebastian Barry 2022 op.cit: 118f.

[24] Declan Ryan op.cit.

[25] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 1.

[26] Jude Cook (2023: 53) ‘Digging Up the Past’ in Literary Review (Issue 516, March 2023), 53.

[27] Sebastian Barry 2022 op.cit: 107 for Barry’s mother and Yeats.

[28] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 86

[29] In the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle-Spoil of Cooley) an Irish king of another domain asks, ‘What manner of man is this Ulster Hound of whom we have heard’ Cited Eleanor Knott & Gerald Murphy (1966: 117) Early Irish Literature London, Routledge & Kegan Paul. The written versions of this poem are medieval but scholars believe them to derive from oral tradition from much earlier. For more see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1in_B%C3%B3_C%C3%BAailnge

[30] Ibid: 231.

[31] Ibid: 127. Treasure Island is used, as are so many other stories including Irish legend, in Barry’s boy’s story Elsewhere (1985), wherein we find the phrase: ‘a sailor must be a father too’ (op.cit: 35).

[32] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 24 & 114 respectively.

[33] Ibid: 233

[34] Adrian Fortescue ’Liturgical Books’ in Catholic Encyclopedia available at: https://www.catholic.com/encyclopedia/liturgical-books. See also: https://www.catholic.com/encyclopedia/liturgy

[35] Sebastian Barry 2023 op.cit: 232.

[36] Ibid: 19

[37] Ibid: 4

[38] ibid: 191.

[39] Ibid: 32 & 8 respectively

[40] Ibid: 219

[41] Ibid: 45

[42] Ibid: 88

3 thoughts on “‘He had a sudden strong desire to tell his story to someone, as long as it was to someone without ears. … Billy and June would have different versions. They were sort of uncompleted chapters, and even when he put them together in his own mind it was hard to find where they joined. Even to believe half of it. But he was obliged to believe it. Because in the first instance a witness should be believed. … He felt he should believe – believe himself’. Stories are not evidence of the truth, are they? But if they aren’t why do we need them? This blog is on Sebastian Barry (2023) ‘Old God’s Time’.”