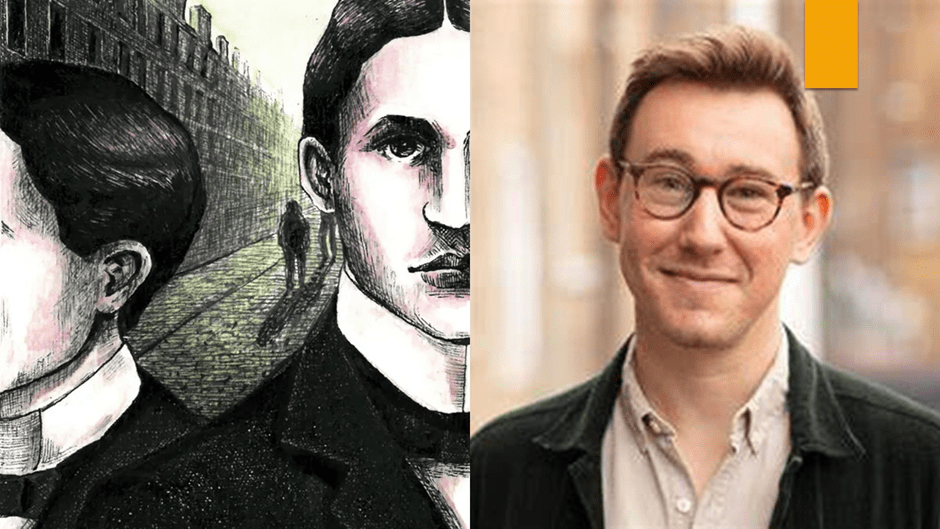

Tom Crewe writes in an ‘Afterword’ to his novel The New Life that ‘I have written a novel, purely with a novelist’s intentions’, despite any other effect of his writing including that of incorporating queer sexual diversity across any supposed binary.[1] I think that not all of what the latter diversity entails is overtly explored and makes the novel all the better. This blog queries what Tom Crewe might ‘intend’ in his novel and what that says about what makes a novel a good novel? It is about Tom Crewe’s (2023) The New Life London, Chatto & Windus.

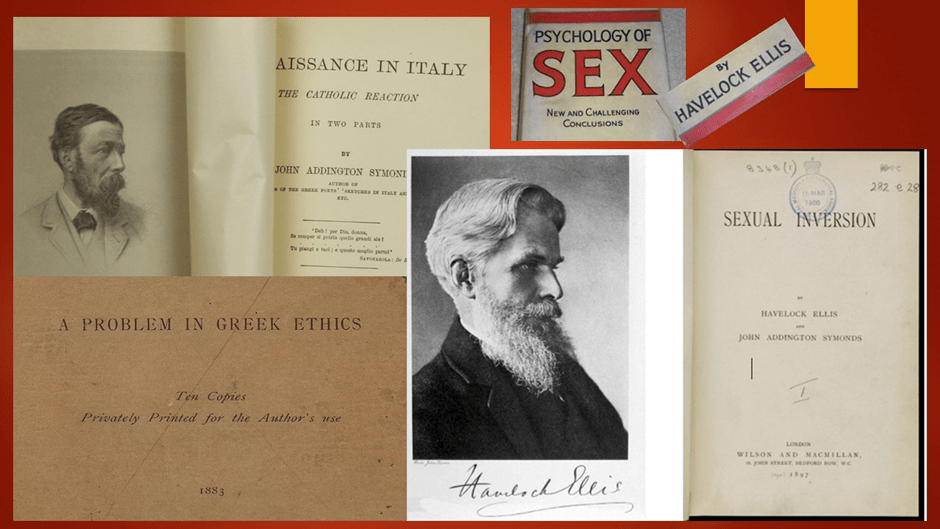

Sometimes it doesn’t matter what a novelist says about his own novel and readers get carried away by their expectations. This was my situation for my introduction to this novel was via Johanna Thomas-Corr’s review of the novel in The Sunday Times Culture Magazine (Justin’s copy whilst he was here). However, I don’t want to be unfair to this review for I stopped reading it (until at least I read the book itself) after its second paragraph. This was enough to make me believe that this was a fictionalised dual biography of a part of the lives of two great early students of human sexuality. Thomas-Corr describes them as ‘two British academics, John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis’, the subject of the book being book in itself: ‘a medical textbook called Sexual Inversion’.[2] Of course I ought perhaps to have already been wary of this introduction for I knew enough to see the essentially misleading descriptors here that name these men ‘academics’ and their jointly authored book ‘a medical textbook’, though both may have wanted the publication to appear to have that character.

Indeed this wanting ‘the publication to appear to have that character’ is part of the story told by Tom Crewe, for he reports the redoubtable lesbian represented as the female partner of Henry Ellis’s wife, Edith (this is largely an invention apart from the fact that Edith is thought to be lesbian) named Angelica Britell saying of the ‘hideous’ (her word) judge in the case saying: “You may have been gulled into thinking this was a scientific book, but anyone with a head on his shoulders could see it was a sham, entered into to sell a filthy publication”.[3] Being ‘gulled’ into believing a book is other than it is may, from the evidence of some of the critical response to a game played by Tom Crewe with his own readers in relation to expectations of it containing historical biography. After all, the character John Addington also pretends to his wife that he is writing an ‘autobiography’.[4]

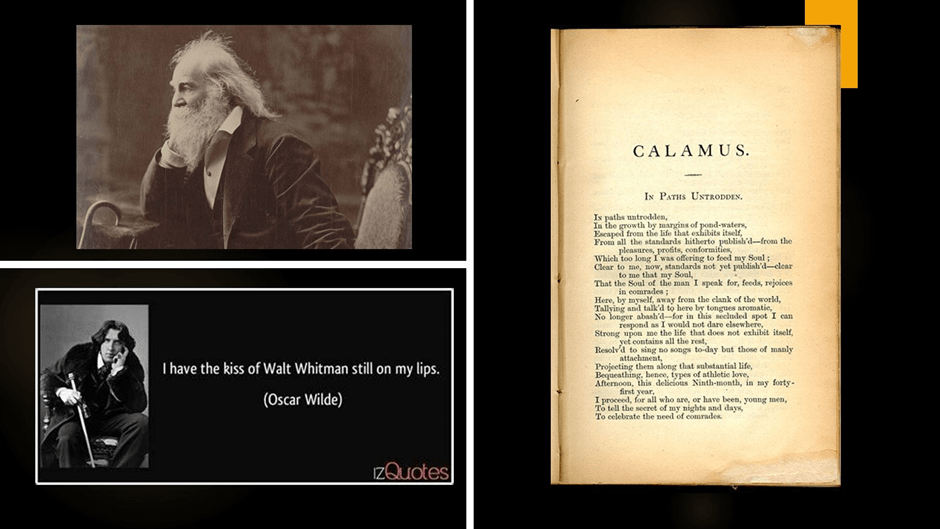

In fact as I hinted in my first sentence, Crewe in his ‘Afterword’ to the novel, not only says unequivocally that the purpose of his book is to be ‘a novel’ written ‘purely with a novelist’s intentions’ (as I cite in my title) but also that it is not historically accurate in relation to the men who inspire his slightly differently named characters: ‘Readers can get an easy sense of the scale of my departures if they recall that Symonds died in 1893, and that this novel begins in 1894’.[5] Such a departure is necessary because the fiction of this novel requires that John Addington faces the challenge posed to queer men of the Oscar Wilde trials, which are crucial to the development of both characters and the novel’s handling of the representation of physical sex between men. This is hardly ‘lightly re-engineering real-life events’ as described by Thomas-Carr. Yet we can see why critics are keen to take this line It is at its worst as an approach in Richard Canning’s overbrief contribution on the novel in Literary Review, for he says that Crewe ‘rarely takes liberties with historical details’ as if that were a virtue. Moreover he too often in such a short review misreads the details of the novel. He says, for instance, in illustration of one ‘historical liberty’, that Crewe ‘avoids going into the fact that Symonds and Ellis had Sexual Inversion published first in then-liberal Germany’.[6]

This misreads the game the novel plays with the historical fact, which I have already alluded to above, and reveals that Canning has read the novel far too loosely (and perhaps not as if it were indeed a novel, as a queer biographer might be forgiven for so doing). I say this because Crewe includes this fact as a potential ‘counterfactual’ (one of two in fact) of the supposed events of his novel, quoting Ellis saying: “The book could still be published in translation. Or we might try America”.[7] This playing games with fact may indeed be what Crewe refers to in the final sentence of his ‘Afterword’, which I read as precisely relating to the counterfactual as a strategy of fictive truth telling: ‘Truth needn’t always depend on facts for their expression’.[8] This is a statement of the literary artist’s ‘intentions’ as persistent in English authors since Chaucer, and in the later English Renaissance, Sir Philip Sidney’s Apology for Poetry.[9]

The emphasis needs to change from that emphasised by Canning, a queer historian, as if it alone was predominant; away, that is, from a too close dependence on the novel’s debt to history. Peter Kispert in The New York Times also takes nearly a biographical historian’s approach to the novel when he says: ‘Altogether, Crewe crafts a meaningful tribute to the pioneering Symonds and Ellis’. However, in the final analysis Kispert argues that:

For all its historical fixtures, the novel is energized by timeless questions: What’s worth jeopardizing in the name of progress? Who should assume the greatest degree of risk in the pursuit of an ideal? …[10]

Hence this blog treats the novel as a novel, as indeed ultimately does Thomas-Corr too if not Canning, as a ‘novel’ dealing with fictions of plot, character and literary writing genres and styles. However, I don’t have much truck with the ideal of the timeless or eternal ‘verities’ of novels: truth is situated in history in my view and, I think, that of Tom Crewe. The novel opens with a dream, that turns out to be what teenagers call ‘a wet dream’. Amongst the critics I read, only one, Lara Fiegel in The Guardian, seems to have absorbed the point of this, for this she says is a novel about historicised embodiment – how the body manifests that is through historically situated core beliefs about it:

Tom Crewe’s virtuoso debut The New Life is one of the most embodied historical novels I have read. The tone is set in the extraordinary opening scene. It’s London in 1894, and John is jostled against another man in a tube carriage, “close enough to smell the hairs on the back of the man’s neck”. John has an erection, “cramped” flat against the man’s body, and the man begins to move his buttocks against him. As the scene becomes more openly outrageous – the man unbuttons his flies and reaches in – it becomes clear that this is a dream.[11]

I will have to cite Fiegel again later for I find her perceptions more than satisfyingly correct in terms of my reading of this book too. Character is explored through and in bodies and bodily events including the feel of , and smell of, body hair in other domains too – such as the neck (as noted by Fiegel in that case), knee and hands.[12] Even pubic hair is imagined in relation to the whole felt weight of the genitals. Watching his working class lover, Frank, in a train, the refined intellectual, who lives apparently very much in the mind, John Addington sees even ‘the smallest movements’ of his earthy lover as the man sits facing him in a train carriage, he sees a man whose body swims through the world of the senses. Vision turns into imagined sense, for this moment is about much more than the ‘gaze’, of the naked body, and the motion of its parts relative to both the desired man’s environment and the imagined bodily interaction between senser and sensed :

…; he merely moved one leg slightly to the right. But John understood immediately that he had done it to free his scrotum, to let it drop away from where it had stuck. He pictured the two globes in their loose snug skin, brushed with dark hairs; he felt in his mind their soft weight, their liquid fullness in his hand.[13]

I cannot know how such a passage will be received by a reader unsympathetic to the world of the imagined body, that sense of the proprioceptive that plays with the distance between that which it senses and that which it desires to sense. It is a bodily consciousness that is not just erotic in its scope for in another episode on a train cramped with unknown bodies it can convey the sense of embodied anomie and distance as well as extreme proximity: ‘They all negotiated their knees. He was pressed close to the window’.[14] However, it is the erotic consciousness of other bodies mixed with insistent imagined desire that is unusual to find in novels and some male critics seem unprepared for it. It can shock, as for instance when John silently desires the body of his daughter’s husband, Stanley, and imagines it in relation to his own pleasured and pleasuring body, ‘those long legs parting his’ as they merely sit together.[15]

The potential embarrassment caused by speaking of such moments is indeed part of the novel’s theme as well as method. In an ironic context, a Free Press Defence Committee, John is blamed by everyone, even those who were there to defend free speech, for reasons ranging from embarrassment, conventions of social appropriateness and strategic political reasons (even Henry’s personal fear of confronting their political aims’ apparent ‘infeasibility’). They feel John is too openly, even if indirectly as regards himself, speaking of queer sex: ‘He stopped. His eyes roved about. The room palpably shrank from him’. [16] Indeed, the novel has the theme of being afraid to speak of queer desires at its centre (and not just related to gay male sexual desire as we shall see). This is most charged around the Oscar Wilde trial where even John is distressed at the exposure of particular detail of Wilde’s sex life, apparently fearing stain and blemish to the political cause of the visibility of ‘inverts’, but still angry about Wilde’s discursive cover for this love: ‘He has brough each and every one of us down with him’.

His fear is almost as much, if not the same, as his wife Catherine’s is for fear of loss of social standing and self-respect related to her husband’s sexuality, and perhaps even with a strain of this fear in himself too, shown in his conversation with Henry in the presence of his lover (passing as an unlikely heavily London-accented ‘secretary’), Frank Feaver. Wilde’s ‘lies’ are they say based on covering up the bodily nature of his sexual practice with idealism associated with the Ancient Greeks, Shakespeare and Michelangelo (which is remarkably like his that of the real Addington Symonds and his book A Problem in Greek Ethics): ‘The Greeks are made to justify the man who pays a boy drunk on champagne to share his bed, who deals with blackmailers as others do with grocers’.[17]

A deeper version of the theme is the omnipresence of Walt Whitman, with whom Edward Carpenter, in this claim true to history, claims he had had oral sex in the most charming yet, to me unfortunately (in public at least), cringeful description of oral sex between men I have ever read: ‘I drank him up, swallowed him down, and went to sleep in his arms’. To which John asks: ‘What did he taste like?’[18] Some people, at least, feel that some questions you are not supposed to ask (perhaps all of us when they touch on the most suppressed of our unspoken desires and fantasies). And Whitman is at the centre of the novel too not only because he tastes ‘Sweet – like age’ but because he fears those ‘natural’ urges that he dare not speak, and perhaps does not entirely know, about his desire, which is not only that he feels sexual love towards men. Crewe tells us that Addington, reading Whitman’s poems, ‘hesitated’ over this one:

I now suspect there is something fierce in you eligible to burst forth,

For an athlete is enamour’d of me, and I of him,

But toward him there is something fierce and terrible in me eligible to burst forth,

I dare not tell it in words, not even in these songs.[19]

Overcoming the fear to speak will be as crucial to this novel as is speaking, for there is even in speaking a way of delivering what you say that will, as Wilde’s case seems to emphasise, matter that will please no-one, even one’s political allies or lovers. To this we must return when we discuss the brilliance of this novel as a means of reliving ethical dilemmas to which there may yet be no solution. For eliciting speech, making it ‘eligible to burst forth’ in Whitman’s terms, employs very complex ambiguities in the word eligible of personal availability and sociolegal authorisation in its expression. Yet speaking out the unsaid, and actively silenced, is the purpose of Ellis and Addington’s book and its questionnaire-based research. Such speech, in the words of the anonymous (to the court at least) ‘cases’ treads cautiously in making ‘burst forth’ ‘into ‘eligibility’ some very private (indeed heavily secreted) answers to very personal questions that perhaps, some feel should not have been asked. This is at its most pertinent when Henry Ellis’s former university friend, Jack (a failed closeted gay male medical student who turns into a bachelor theatre-critic) is questioned (by his own choice admittedly) in the presence of both Henry and the latter’s wife, Edith – the latter acting as note-taker. Even for Henry, this is a moment full of dread that isn’t helped by the unspoken association in the descriptions of the weather (an effect that characterises the brilliant novel throughout): “Filthy, isn’t it?” Henry said from the sofa’.

He could tell immediately that Jack was nervous and thought Jack would notice that he was equally so. They knew each other too well to make this kind of exposure, at this point in their lives. Yet there was no way of avoiding it; it had the inevitability of the section of a corpse on a bench.

The embodiment of Jack as dead here is chilling, the forensic nature of the inevitabilities assumed equally so. Jack will regret being questioned and more so giving answers about masturbation (Crewe at his ludicrously comic best makes Henry hear Edith’s ‘pen scratching’ in the background to Jack’s initial embarrassment) and sexual positions – though only the binary options of ‘active’ or ‘passive’ get allowed in this questionnaire (how unimaginative methinks!).[20] Yet John’s take on this is is exemplary and that of the true advocate of the moral health of all aspects of embodied sexuality and shared love. In the collected questionnaires he finds: ‘Every man who trusted us with his history. Our assertions of the blamelessness of our lives’.[21]

Yet the fear of open speech about the body, which John calls a fear of physical ‘stain’ (‘as if it would stain your tongue to speak of it’) is often embodied in the fear of stains on bed clothing seen by servants or others outside of families, bourgeois or otherwise. The book depends, for instance, on us knowing the fear of sex observed by another even in the imagination; hence his rightful fear of the ‘pretty’ maid, Susan, ‘who he knew collected the dirty things’ (what a wonderful phrase). Susan, after all, could interpret the ‘succession of pungent patches, smears’ on her employer’s sheets and will, in the fullness of time, use accumulating evidence that this applies to his relationship to his ‘secretary’ Frank to covertly, if modestly (for she only wants her wages extended till she find another position), blackmail him .[22]

As Fiegel says, so beautifully, the covering up of stain (John’s wife Catherine prefers the word ‘blemish’) is not confined to her alone, for it affects the working-class Frank and his disabled mother, who may even (and is the more likely so than John) go to prison if exposed as a gay man. The latter can say to John about the exposure: “You’re dooming me”.[23] This mirrors Catherine and is put beautifully by Fiegel:

“Tell me: is the injustice that I have suffered the stuff of a book?” she asks, complaining that she hasn’t had her husband’s freedom to bring strange men to the house and that for him she’s been “merely flesh, fitted to receive your waste”.[24]

Like Susan dealing with stained sheets, Catherine has still to ‘launder’ social reputations from ‘stain’ (since it will be seen like this whatever her tolerance to her own domestic arrangements) not caused by her, and which she had even less freedom to have initiated. Her demand that her daughters, herself and this ‘house shall remain without blemish’ is surely brilliantly vindicated in the nuanced dealing with moral and psychological complexity in this book .

But I think we have to bite the bullet here and critique the campaigning defenders of the ‘born this way’ binaries of sexual life too in dealing with this theme. Queerness is not merely about gay male desire but about desire that outstrips convention, in women, men, or LGB and ‘straight’ persons, and in the whole complex shadow of the range of possible sexual identities, whether seen as temporary or permanent. Hence the need for that otherwise clumsy LGBTQI+ term and the ambiguity on the Q as meaning both Queer and Questioning as per choice. The novel brilliantly deals with issues of the unspoken questions about sexual practice that both are and are not seen as available for social resolution or answer. This includes issues, now commonly shared, such as sexual failure or chosen abstinence, masturbation and narcissistic optical self-pleasure, the role money plays in obtaining sex (sometimes subtle as in the financial status differences between John and Frank, sometimes frankly about prostitution – male or female), the confluence of awareness of the ‘relief’ available from sexual or urinary ‘incontinence’ and, of course Henry Ellis, whom though heterosexual, has a largely unspoken ‘sexual peculiarity’.[25]

In this matter, for example, my own interpretation differs slightly from Lara Fiegel’s, I think. She expresses Henry’s sexualities thus: ‘He’s straight but has his own sexual peccadilloes; again like his namesake, he’s aroused only by the sight of women urinating’.[26] Though this ‘secret’ may be true of Henry Havelock Ellis (and, if so, I am sure Crewe will be referencing it), I think the evidence for asserting this in the novel is less sure. There is a play, of course, on the phrase ‘relieve myself’ when Angelica uses it to describe her need to urinate and its follow-up use by Henry Ellis to describe and disguise his prompted need to masturbate.[27] Yet otherwise what matters most about the treatment of Henry’s ‘peculiarity’ of sexual interest is the fact that he will not speak of it, even to answer direct questions, whether the questioner is queer or straight, either or neither. Indeed Henry is most fired by John’s speech on the invert when it touches on ‘hidden conflict, a forcible suppression of the sexual impulse’.[28] Even when he tells the nature of the peculiarity to his lesbian wife (‘the first person he has ever told’) we are not made privy to the secret. We only know it shocks Edith, whose role otherwise is to be a free thinker about such matters. Nevertheless, once she knows, she finds it to be a ‘relief’ that the blame for their failed sex life is not hers, something she cannot offer to Henry – except as a future hope that someone ‘will understand’ his desires.[29] The very fact that the reader may not be one of those persons remains a possibility for they are not trusted.

Moreover Henry’s sexual ‘peculiarity’ has I think several characteristics including a great deal of auto-eroticism triggered by his own body emissions (the sweat collected ‘at the back of his scrotum’, for instance) which make him feel ‘wondrously alive, like a marvelous secret kept and discovered by himself’.[30] Obsessing about other people’s emissions are but a step from this. Then there is his inexplicable, even perhaps to him, attraction towards an unknown ‘dead drunk’ woman, who appears – unnamed – twice in the novel. On the morning of his wedding to Edith, he sees her through a window and becomes fascinated by not only her fall but the possibility of bodily emissions that might soil his ‘wedding suit’ were he to assist her: ‘’What if she were to vomit, or be bloody from her fall?’ He begins to ‘fiddle with his tie’. He even examines the place of her fall afterwards finding not blood but a ‘small piece of jewellery flashing light’, which he keeps despite (or because) it is ‘cheap’.[31] When he believes he sees the same woman again, we still are no clearer about his fascination for tries ‘to make the woman perceive his waiting, define his purpose’. Nevertheless, that purpose relates to the event in which Angelica relieved herself, although with this woman, poor and abject, it would, he thinks, be ‘easy to impose himself and his will on her’ for she will give him what he dare not ask of his wife. It leads him straight to an act of combining masturbation with the jewel he found earlier ‘tight in his spare hand, pricking the skin’.[32]

What version of queer heterosexual sex this covers I hesitate to label, just as the novel does. Even Henry in self-reflection feels that ‘he did not know where to take his desire’.[33] Yes! It combines a fascination with emissions, including urine, but it also link to pleasure in pain, satisfaction in and by the embodied feel as pain of the presence of the other. This obsession with a subjected woman associated with ‘pricking’ pain is very complex. But maybe I take this too far and Fiegel is right. In the end I think the purpose of Henry’s sexual ‘particularity’ is to force us to see that there is more to the concern with sexual diversity than the championing of inverts, people supposedly ‘born that way’ and that has to do with the sexual incompletion of individuals and the questioning of its meanings with others. In this, I think, Crewe may think like Jana Funke, who gives her views in a fascinating blog on the use of the book Sexual Inversion to understand queer politics.

In identifying her aim to highlight ‘alternative, richer and more multi-layered understandings of sexuality’, she says (and I quote at length but miss out her main evidences) that concern solely with a gay politics that defends those ‘born this way’ but not the ‘choice’ of queer sexualities may:

unintentionally perpetuate the notion that homosexuality is somehow less desirable if we argue for social acceptance and equal rights on the grounds that we simply cannot help the way we feel, … / … Ellis and Symonds’ correspondence suggests that they also struggled considerably to make this argument work and that they were all too aware of its flaws. …/ Although Sexual Inversion does anticipate today’s ‘born this way’ argument in interesting ways, …. While the idea that homosexuality was necessarily inborn or congenital was a useful strategy to work towards political goals, it also had considerable limitations and certainly did not capture all individual experiences never mind different cultural and historical understandings of sexuality.[34]

I would say this view is one the novel supports precisely because it is a novel and not a political history or biography of a scientific career spent in the field of sexology. There is in the constant referencing of natural rights of the ‘invert’ in the John Addington in the novel that has something of a shrill denial of diversity and a closing down of empathy for others or even one’s fellow-travellers, who fail to meet a purity of belief about the sacrosanct nature of campaigning about an issue seen as necessarily separate from other ways in which heteronormativity and homonormativity both constrain us as beings and deny diversity in ourselves and others, especially (as I say) our allies. There is something extremely problematic about John Addington’s treatment of his wife and family (as there is sometimes of him by them) which argues that ethical issues cannot be divorced from choices about our self-promotion and which, likes knees in a cramped railway carriage, be accommodated. Here again Fiegel gets it right:

Crewe’s brilliance – in addition to his ability to make us feel the physical sensations – is in dramatising moral dilemmas with complexity and rigour. He’s especially good at exploring the perennial conflict between private and public acts of courage and openness.[35]

Those ‘moral dilemmas’ include dealing with every diversity of sex/gender as well as openness to diversities in the response to the body within sexual activity and its functions, even those that shock us and make us uncomfortable (provided they are consensual and based on equality of understanding which must exclude anyone unable to fully understand or consent). I think John is not only failing ethically with Catherine (though I do not doubt the difficulty in both their circumstances) but with his lover, Frank because he over esteems the power of his ‘pen’ and the entitlement it gives him – almost as if it were the symbolic phallus or pen(is) of male authority. John ‘trusted to the power of his pen,…’, we are told when he stands out against Catherine’s fear for her own safety.[36] He ignores the vulnerability of the Higgs’ and, indeed of, Ellis. Ellis is, as we have seen, not even sure of what about himself he is protecting. Catherine sneers, for instance, at Henry’s inability to understand his own motivation in supporting inverts which she sees as a ‘sordid, squalid subject’ but John himself is no more understanding of the issues relating to Henry here than his wife. Yet he happily misconstrues Henry’s answer to his question : “Why did you want this, Henry?’. Yet failing to understand the answer or listen long enough, he merely draws Henry in to alliance with what he can understand.[37]

Do these two men understand each other?

Personally, what hooks me about this novel are phrases in it, that I barely know what to do with other than admire their reach downward to depths of haunted, almost tremulously neurotic, beauty. They certainly can’t be explained as just ways of telling the story in a brilliant and psychologically engaged style. One is in the opening account of the ‘wet dream’, I talked about a lot earlier. There, in the carriage and the dream both, in a moment of involuntary sexual fulfilment, John feels ‘his entire consciousness constricted, committed to their small circle of subtle movement’.[38] For me this perhaps tells us a lot about obsession that moves only in a ‘a small circle’ and which though it creates subtle progression is still difficult to take in and understand in full, for it is a movement never fulfilled in itself. It is perhaps life itself as it varies adaptively.

And if it explains John’s deep motivation for his obsession and perhaps even Ellis’ at some moments, it also might say something about Tom Crewe’s motivations here – to express his obsessions but remind himself that the world we live makes demands that we grasp large issues – social, psychological and ethical. It is perhaps the basic demand that we do not neglect ‘otherness’ in the embodied other in pursuit of our own. In that sense the key statement of the novel is Frank Feaver’s to John that his obsessive and compulsive actions circle around something smaller than he thinks it is: ‘“You’re thinking of yourself,” Frank said, … “But it’s only a book – you’re forgetting, It won’t save anyone. One book never did”’.[39] If this was part of Tom Crewe’s conversations with himself when he doubted himself about this book, I wonder what Andrew O’Hagan said to him precisely in his ‘fizzing pep talk’ when they met to discuss the author’s self-doubts in ‘early 2017’.[40]

I think, whatever it was, we should be grateful because this is a great and splendid novel, that does what novels should do. It renders up a complex world of the intersecting real differences implied by psychological and social diversity (including sexual diversities) in its genuine complexities as reading matter. Do read it. It’s better than I make it sound, for I write this mainly for myself.

Love

Steve

[1] Tom Crewe (2023: 373) The New Life London, Chatto & Windus

[2] Johanna Thomas-Corr (2023: 20) ‘Forbidden love in Victorian Britain’ in The Sunday Times (Culture Magazine) [8, January 2023] pages 20f.

[3] Tom Crewe op.cit: 364

[4] Ibid: 239

[5] Ibid: 373 & 371 respectively

[6] Richard Canning (2023) ‘A Very English Scandal’ in Literary Review (Issus 515 Feb. 2023), pages 55f.

[7] Tom Crewe op.cit 355

[8] Ibid: 373

[9] Sir Philip Sidney The Defence of Poesy. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69375/the-defence-of-poesy

[10] Peter Kispert (2023) ‘The Gay Rights Movement Before the Gay Rights Movement’ in The New York Times (online) [Jan. 3, 2023] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/03/books/review/the-new-life-tom-crewe.html

[11] Lara Feigel (2022) ‘The New Life by Tom Crewe review – desire on trial’ in The Guardian (online) [Thu 29 Dec 2022 07.30 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/dec/29/the-new-life-by-tom-crewe-review-desire-on-trial

[12] Tom Crewe op.cit: 3f., 100 & 189 respectively.

[13] Ibid: 154

[14] Ibid: 351

[15] Ibid: 252

[16] Ibid: (for Henry 320) & 329.

[17] Ibid: 231

[18] Ibid: 204

[19] Ibid: 85f. (Crewe’s italics but my bolding for emphasis)

[20] Ibid: 173 – 177

[21] Ibid: 231

[22] Ibid: 7

[23] Ibid: 344

[24] Lara Feigel, op. cit.

[25] Failed heterosexual sex (all page reference to Tom Crewe op.cit) 62, prostitution and money for sex ,72, 181, 237, urinary sex 75, 216f., 262f., narcissistic self-pleasure 29, unspoken peculiarity 328, 360,

[26] Lara Feigel, op. cit. (my bolding)

[27] Tom Crewe op.cit: 216f.

[28] Ibid: 328

[29] Ibid: 360f

[30] ibid: 29

[31] Ibid: 12f.

[32] Ibid: 262f

[33] Ibid: 261

[34] Jana Funke (2014) ‘Born This Way? Sexual Science and the Invention of a Political Strategy’ in NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality [Website – July 15, 2014 in LGBTQ section] Photo: ‘Born this Way’ (Credit: Quinn Dombrowski / Wikimedia Commons) Available at: https://notchesblog.com/2014/07/15/born-this-way-sexual-science-and-the-invention-of-a-political-strategy/

[35] Lara Feigel, op. cit. (my bolding)

[36] Tom Crewe, op.cit: 185

[37] Ibid: 309 & 243 respectively

[39] Ibid: 238

[40] Ibid: 375