Mark McGurl asks what he believes is a new question in querying the ontology of the novel ‘when intermixed with the rough-and-tumble of real-time global communication and social media’. It is, in brief, no longer an issue to talk about the commodification of the novel, since we need instead to focus on the ‘progressive commoditization of the novel. The commodification of the novel by contrast is an old story, a given, as important as the fact remains: novels are offered for sale’.[1] This blog attempts to come to terms with an understanding of the processual issues in commoditization as a way of examining the history and theory of the novel as it is developed by Mark McGurl (2021) Everything and Less: The novel in the Age of Amazon London & New York, Verso.

Let’s start by explaining the terms that matter in this blog and, I believe, in Mark McGurl’s important book: commodification (the prior and better known term) and commoditization. Definitions of each term from Wikipedia can be accessed via the link on each word. However, let’s start a specific discussion of McGurl’s use of them with his own simplified, and perhaps reductionist, definition cited in my title of the first and better known term (‘better known’ because it is the prior process perhaps): ‘The commodification of the novel … is an old story, a given, as important as the fact remains: novels are offered for sale’.[2] Things become commodities, that is, when they become sellable, sometimes demanding for them a change of form to something tangible. Interest in this process is as old as the novel itself considered as a form intended for wider distribution than a limited audience. Commoditization, in complete contrast, describes a continuing process. It is defined by McGurl as: ‘the reduction of intellectual property to a less and less profitable – because increasingly interchangeable and widely available – class of generic goods’. (ibid; 255).

But let’s return to the ‘old story’ for a moment to see the state of play into which McGurl intervenes. One of the most recent comprehensive discussions of commodification that I know in relation to art is Nicholas Brown’s (2019) chapter ‘On Art and the Commodity Form’ which is the introductory chapter of his book Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art under Capitalism. It is a worthy text in its disentangling of many knots in the Marxist approach to art but not one that will appeal to those uninitiated already into the arcane debates about the supposed autonomy of art (at one point he helpfully describes this as a claim that artworks are ‘self-legislating artifacts’).[3] For those who want to go there and feel equipped for the interplay of Marxism with other philosophical schools originating not only in Hegel but also, and primarily, Kant, you will need to go to the chapter itself, for I don’t feel equipped to explicate the issues.

What is crystal clear in the argument is that the central issue of whether, for good or ill (for the neoliberal right and the socialist left respectively) art is at ease with ‘the commercialization of culture’ or subjected to ‘the wholesale reduction of art to a commodity’ is paramount in beginning to describe what art is, its ontology.[4] But Terry Eagleton’s words cited as the example from the ‘left’ here possibly overstates the case when we consider the internal differentiations within art between art of greater or less value qua art which are not conveyed by the idea of ‘wholesale reduction’.

Neither of these characterizations, which approach commodity culture either favourably or unfavourably, satisfy the issues in Brown’s argument for above them lies another question (namely, is art more than a commodity?) that requires satisfaction first even if we accept that it is a commodity in part. For it is there, in my view, that art is at its most apparently ‘self-regulating’. In considering values in art connoisseurs and critics alike most often authoritatively distinguish aesthetic values (whether of form, meaning or both) from both of the concepts Karl Marx employs in Capital to analyse the phenomenology of the market for commodities as a whole.[5] For ‘great art’ oft is considered to be that for who the market is self-limiting – John Milton’s ‘fit audience though few’ – and which can be considered not to partake of any immediacy of utility.[6] Nevertheless, this is not how Nicholas Brown handles the argument, I think, and in this he is typical I would say of the Marxist social critique of the relationship of ‘art’, ‘culture’, and their artifacts, to its ‘wholesale reduction’ to ‘commodity form’.

In essence, Brown and other academic Marxist theoreticians of the arts oft reject Terry Eagleton’s statement not by denying that art has become a commodity but in affirming that it is hasn’t been entirely ‘reduced to a commodity. Let’s try another way of stating the question they try to answer. Can art be conceived as something more, even if not something else, than a commodity? Brown sets out to establish a view that seems to be the postmodern socially critical consensus, that art is autonomous in as much as it exposes the contradictions underlying the mythology of both its dependence and autonomy from the commodity form it inevitably has to have in a capitalist society. It is, for instance, not able to articulate a politics except by fulfilling the purpose of describing the world as if political statement was not its object: hence ‘the antiracist politics of J.M. Coetzee, the feminist politics of Cindy Sherman, the class politics of Jeff Wall, and the culture-industry critique of Alejandro González Iñárritu are compelling only, and precisely, because they appear to emerge as if unbidden from the material on which these artists work’.[7] The ‘as if’ in this sentence leaves every question about authorial or other intentionality in the work of art open wide but which fit nicely with the idea of the transcendent value of art that does not align solely with the received values of life in everyday practice of the production, distribution, and consumption of its artifacts.

What the view I cite above then (from the end of Brown’s introductory chapter) leaves us with is that such a phenomenon is as dependent on a notion of the hierarchy of artistic value (from great art to popular art) as ever – only the great achieve this ‘as if unbidden’ status of their politics. It does not explicate art outside such critical and hierarchical distinctions. In a sense all art is a commodity but great art in some way transcends its ontology in some higher noumenal realm, as in Kant. Hence Brown discusses only works he considers to be ‘great art’, such as that in the list in the quotation in J.M. Coetzee represents the novel at its most transcendent value, In effect the discussion of any art, especially in the academy, remains what it was – there is worthwhile art and there is art that meets mundane needs that does not even aspire to greatness, though contingently, it may have that term ‘thrust upon it’, as in societies in which capitalism emerges from feudalism was oft the case for an aspiration class.[8]

In my reading, Mark McGurl sees this debate as essentially an empty one – obsessed with an ontology that preserves the distinctions between forms of the novel (for that is the only artform he considers) at the expense of making new claims about the function of disruption in capitalism: for disruption might disrupt more than the market. And for Mark McGurl it does, though he seems to be on the cusp of the analysis of its present effects (in many paradigms communicated in innovative graphical form) rather than presenting it complete. That is because ‘The Novel in the Age of Amazon’ is an emergent form for which the criteria of value are disrupted both in terms of its commodity value AND in its internal value as an artform claiming special status for its privileged members only. What is most exciting about McGurl’s work are the disruptions of critical discourse, that served for instance by departments of national literature in large, about ‘the literary novel’ as opposed to the non-literary novel. Hence the questions raised by the semi-pornographic Cocky novels impel themselves too into the way literary novels are read, at the level of their production, distribution and consumption certainly but also at the level of the human needs they are seen to serve, which in the ‘age of Amazon’ can be seen to have commonalities.

McGurl discusses the Cocky novels (an apparent series but in fact based on the endless repetition by different authors of the same formula) as published by KDP from the point of view of a consumer scanning Amazon Books. The view may not be the same, of course, in the eyes of competing authors presented in the list or not of their own version of Cocky. Faleena Hopkins was so sure that copyists had used her formula for Cocky novels in her successful novel Cocky Roomie: A Bad Boy Romance Novel (2016) that she sued Tara Crescent on the basis of the latter’s Her Cocky Doctors: A MFM Marriage Romance (2017)> In fact the trend in Kindle publishing was probably set by Penelope Ward and Vi Keeland by their Cocky Bastard (2015), which Hopkins sort of admitted, once she had dropped her hopeless legal case based on one word in a book’s title ostensibly by copying the formula of Cocky Bastard as Jake Cocker and spawning a new ‘series’ of Cocker brother novels.[9]

Part of an Amazon page discovered on the basis for search for material using the keyword Cocky.

McGurl’s story is a delightful story to retell (so I did above) of the vanity of human beings but is less important than the central point of McGurl’s chapter on what the Age of Amazon had done with a genre we can call “Erotic Romance” fiction, which he describes in terms of ‘the conventionality of its kink’. He makes the point that all of the Cocky novels replicate the genre of novel made first significantly popular by the boom novel Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James, published digitally in 2012, that uses the scenario of a woman being bound (literally) to a powerful man (in body and financial and social status) but taming him in marriage, which he beautifully summarises thus: ‘What are a few whips and chains and cable ties against the formation of a couple of such blinding whiteness and rigorous heterosexuality?’[10]

And more importantly he traces that genre back to novels often associated with the term ‘masterpiece’ or at least ‘great literature’, even though their eroticism is often differently encoded. And in doing so he made brilliant comparisons, with the aid of a feminist explorations that preceded him, to the fact that the claim made for this (even the Cocky fiction), is that it ‘flagrantly satisfies the “imaginative needs of the community” (a claim that is also in, he argues, the academic Northrop Frye’s famed view of the romance genre in the 1957 classic literary work The Anatomy of Criticism) can also be made for the wider genre of romance fiction that is, unlike the Cocky novels, considered great literature or part of its conscious tradition.

He cites for instance, with stunning conviction, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, and even more complicated cases, such as Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, about which ‘we have no trouble calling masterpieces’. This ability to show how this works is brilliantly put into the foreground of thinking by his ability to cite critical analogues in feminist critics such as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar about the anxiety of literary authors to being ‘lumped’ together with female writers of the romantic novel, a structure of feeling that probably even holds fast in instances like that of A.S. Byatt in the late twentieth-century.[11]

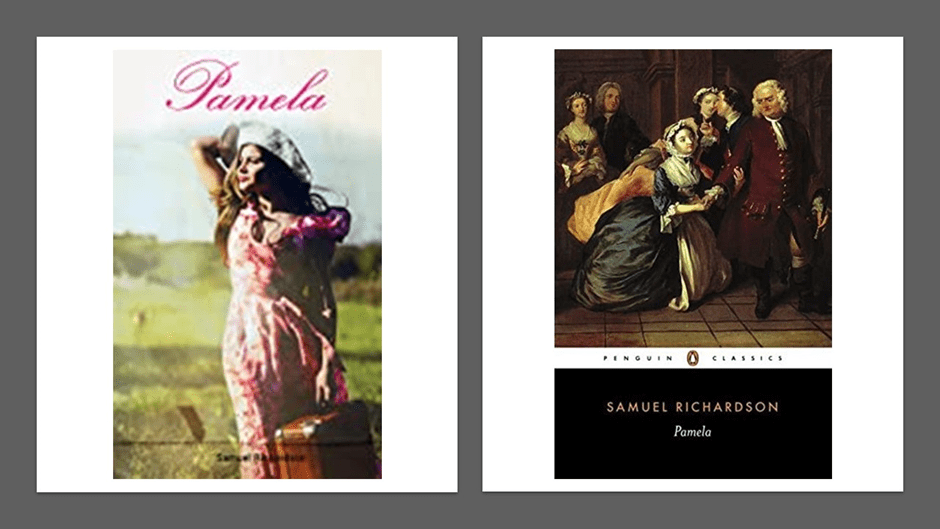

Amazon, and especially Kindle publication, embraces this ‘honest’ appeal to the ‘imaginative needs of the community’ however narrowly the idea of ‘community’ is circumscribed even down to the limitation of audience size proclaimed in the idea of feminist female readers. For Kindle has its own cheap, sometimes free, versions of the range of literature we might call ‘the classics’. In advertising these, it oft uses imagery that remarry them to popular romance – even erotic forms more rarely – by emphasising marriage into wealth and the control of male power. Hence, I use in the illustrative collage above the examples of classic novels in their pictured Kindle covers. His house or his lands sometimes substitute for his dominant look; that look often directed downwards, at the heroine. See, for instance a comparison with the way the Penguin Classics series sells Richardson’s Pamela compared to the Kindle version, which conveys a boldness about Pamela herself that rather obscures the vast class and power differentials in the eighteenth-century novel (although that both are available through Amazon is important).

What McGurl argues is that rather than show novels in terms of more precise differentiation of socio-cultural provenance, and quality, it emphasises the uses of the example for the reader who might be attracted to the themes of the genre of novel to which it belongs. And ‘literary fiction’ is not by necessity a distinct genre for some readers, a fact that McGurl constantly wrestles with in this book, for Amazon too can serve the needs of a community whose self-image demands that it is interested primarily in ‘literary fiction’. Hence the ambivalence of some writers across the genre of romance fiction and literary fiction:

(Jane) Austen, even more than Shakespeare or Dickens, is no doubt the supreme example of a writer who continues to attract maximum amounts of both popular love and critical scholarly esteem. She is an avatar of the genre turn avant la lettre.[12]

And Marxist literary criticism has been no more successful in capturing the specific disruption of the ontology of literary forms like the novel in process through the historical shifts characterising the Age of Amazon. In brief, he says regarding this, that ‘analytical frameworks derived from the Marxist account of industrial production’ are, if used alone, inadequate to understand Amazon’s consequence as a driver for new values in the understanding of what novels are and do that might today be driving the novel today because, ‘for all its sprawl, Amazon produces very little in the traditional industrial sense, the overwhelming bulk of the enterprise being devoted to one or another form of warehousing, sales, and fulfilment, …’. It needs additional but related insight from Marxist feminism usually known as ‘social reproduction theory’.[13] And ‘social reproduction theory’ must account for effects of distribution (‘warehousing, sales, and fulfilment’) often missed from Marxist accounts of the economy and yet so central to any understanding of service or ‘gig’ economies and the success of modern capitalism to minimise the power of workers as workers.

At its most ambitious this book explains that the Age of Amazon is about an existential problem it puts ats its centre: the ‘management of time’. This is not just because of the reduction of the time between the expression of a putative desire and its fulfilment made possible by Amazon systems but the ways in which it structures the act of reading to emphasise the fact that literary, both great and otherwise, emphasises the idea of time, at its best utilising the reader’s reading experience as a use of time that needs an equivalent in satisfaction in basic psychological needs. In as much as these needs are those which reproduce the status quo they are therapeutic needs, enabling the user-reader’s insertion into the difficulties and contradictions of their present circumstances and offering imaginative recompense, even sometimes recompense for the fear of death. Here is the point using economic terminology, notably that of ‘opportunity cost’ sometimes missed by Marxist critics.

But death is only the most final and total of the many limitations of embodiment that infuse works of novelistic realism, precisely to the extent that they are realistic. Here, in the interplay between these limitations and the “imaginative possibilities” of fiction, is where the novel asserts itself as a commodity with a specific existential utility: it is a therapeutic instrument for managing the problem of opportunity cost. The realistic and the romantic or fantastic in literature stand at two poles in the calculus of trade-offs in a transaction between referential gravity, or pseudo-relevance to the reader’s life, and something like escape velocity, freedom from natural and social law.[14]

I find this paragraph rich, but it also illustrates the fact that this is not an easy book to read or digest. It is a book paying study and reflective contemplation, especially around terms like the ‘” imaginative possibilities” of fiction’, for they are hard to understand without a back-catalogue of reading experience of novels of different kinds in the emotional and cognitive schema in the mind of the reader of this book. Romance books may conclude with a happy ending and marriage (sometimes each encoded as each) but the joys of the genre are in the repetition of the reader’s experience with different men, each man powerful, but each dead to the reader in their next novel in the same genre, and these effects are enabled by Amazon marketing and recommendation strategies, as McGurl shows. Romance thus serves reproduction functions that are socially and psychosexually conservative but is also, in McGurl’s terms ‘useful subversion’ (subversion of norms that can be as repeatedly restored at the end of a reading that are then challenged when you read another of the same. As McGurl defines ‘subversion’ it:

in that context is only really the act of producing healthy variation on a continuing theme. What we’re drawing attention to here is not the singularity of the literary encounter but its repetition, to everything that aligns it with the “re-” in reproduction.[15]

This characteristic of the Amazon system (seen from selection of an item that will satisfy a need to its end-fulfilment from a ‘Fulfilment Centre’) saves time because the identification of repeated therapeutic input to by the system from a store that is, at least in appearance, so infinitely stocked, promises a kind of gratification without a necessity of ending. Indeed it prioritises awareness that what we read is always in the context of the ‘great unread’, where great is used quantitatively.

Perhaps the most brilliant perception of this book in my mind is the reading of the fact that much of Amazon’s catalogue is ‘surplus fiction’; in great excess to the chances of reading or even desiring to read all of it. Hence our dependence on its selection hints, which we know to work. To try and read it all, or to write one a fiction and sell it of our own is embraced in this system and thematised as ‘a waste of time’. The Amazon system, purely by the operation of its model as a bookseller, distributor and publisher claims to give ‘readers what they want’ at the cost to some writers who publish through their KDP service who get ‘lost in a sea of content, have no use to readers at all’. And hence they become the ‘” great unread” as Margaret Cohen has called the copious leavings of literary history, the books we never talk about, have in our understanding of contemporary literature’. In effect, McGurl insists this merely apes an effect of the belief in literary scholars and connoisseurs that literature is so structured by nearly unquestionable canons that only great works count and should last so that ‘the number of works of the past understood to be relevant to scholars and their students is drastically reduced’.

Similarly ‘scholars of contemporary literature converge on a relative handful of recently published texts’. [16] The ‘great unread’ therefore exists in both systems, eradicated from concern by different social mechanism. In my own view to question the effects of one system should be to question the effects too of the other and make it part of our understanding of how current capitalist systems reproduce themselves and change never occurs in any significant way. For scholars this is the point of their seclusion and privilege (real or imagined).

One surprising piece of information from the book for me concerned the fact that Jeff Bezos (Amazon’s founder) attributed his initial experiment to reading The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. Apparently moved by its reflections on the consumption of ‘free time’ by write reflections on the time in which he was bound to an employer and historical contingencies (the rise of British Fascism) that he did not understand. Bezos is thought to identify with the butler Stevens because he experiences in the present a necessary ‘transformation in the ideal of service’, and this is how Bezos conceptualised his and Amazon’s business model and mission. Conceiving Amazon (‘that whole sprawling enterprise’) as ‘in a sense, a reading’ of The Remains of the Day, he says of the novel that it is ‘an act of time shifting, compression and dilation, an act not so much of filling up otherwise boring “empty time” as of carving out space for sentiment as against the relentless demands of work’.[17]

This blog has been really for myself – in that sense like much of the KDP catalogue. It worries away at issues I have oft thought of as unanswerable questions. I needed to do it because I am grateful to this book for, in my view at least, providing the beginnings of highly significant answers to those questions. I’d love to talk it over with someone who has read it.

Love

Steve

[1] Mark McGurl (2021: 18) Everything and Less: The novel in the Age of Amazon London & New York, Verso.

[2] ibid: 18.

[3] Nicholas Brown (2019: 28) Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art under Capitalism Durham (USA) & London, Duke University Press.

[4] Cited ibid: 1.

[5] There is a good discussion of those concepts and their interaction within Marx’s text by Brown in ibid: 2ff.

[6] Milton Paradise Lost Book VII: 30ff: “still govern thou my song,/ Urania, and fit audience find, though few.

But drive far off the barbarous dissonance / Of Bacchus and his revellers, the race / Of that wild rout that tore the Thracian bard / In Rhodope,…” See: http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Milton/pl7.html

[7] Ibid: 38.

[8] TWELFTH NIGHT (II, V, 156-159): ‘MALVOLIO: “Be not afraid of greatness: some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em.” See: https://www.owleyes.org/text/twelfth-night/read/act-ii-scene-v#root-72002-68-68/81062

[9] Mark McGurl (2021: 185ff.) Everything and Less: The novel in the Age of Amazon London & New York, Verso

[10] Ibid: 165

[11] Ibid: 170f.

[12] Ibid: 171

[13] ibid: 157f.

[14] Ibid: 140f.

[15] Ibid: 162

[16] Ibid: 257

[17] Ibid: 58f.