NEW EVENTS ADDED: A Preview of the Highlights on my visit with Justin to London from Monday 17th – Wednesday 19th April 2023: Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle at The Barbican 19th April (1100) and a streamed event on return (20th April – Good C. P. Taylor live-streamed from Harold Pinter Theatre!

The Barbican and the Gala (live-stream from London at latter)

This is an addendum to the preview of the items on the culture-fest-trip Justin and me are making to London (for access to the blog use this link). Since writing this we booked another event – for 11 a.m. on the day of our return. We had to, because to see Alice Neel pictures in the flesh is is a rare opportunity, worth getting tired for. The next day, when we are at home, we go to see a special production of C.P. Taylor’s Good live-streamed from London’s Harold Pinter Theatre. We might feel the tiredness then. Again I will look at each event separately.

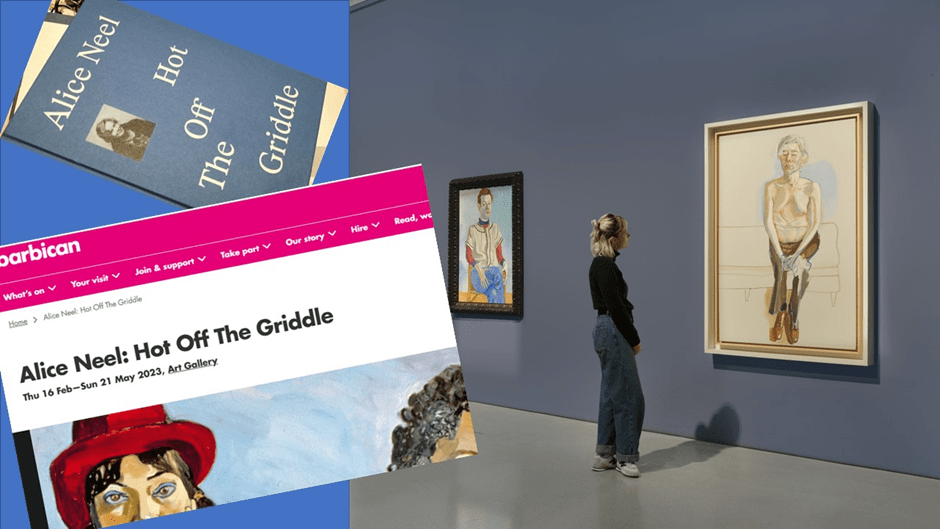

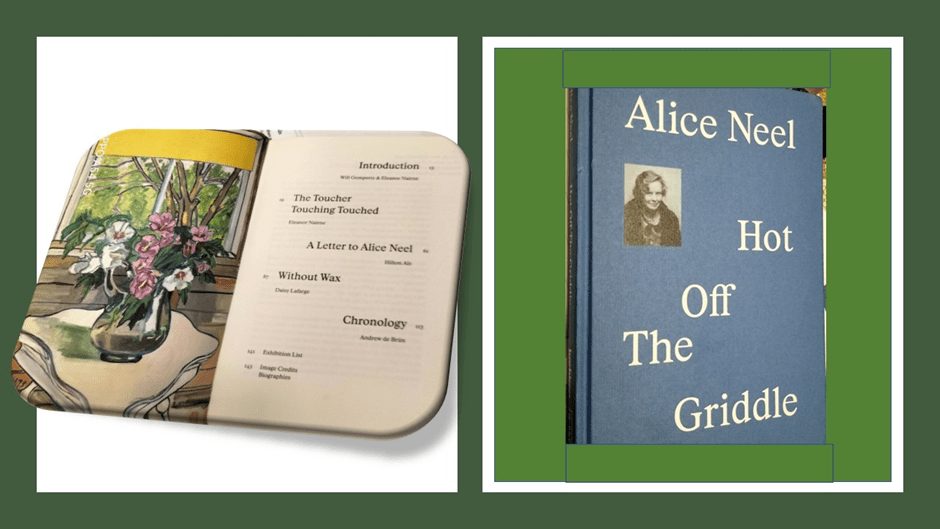

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle at The Barbican Centre Gallery, London, with reference to the beautiful innovate catalogue: Will Gompertz & Eleanor Nairne (2023) Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Munich, London & New York, Prestel-Verlag.

The Barbican has provided its own preview of the show as it is in situ in its austere interiors on social media. It looks like a great event using the generous proportions of the Barbican’s gallery spaces in the best way possible. This is enough to tempt me because I know the painting and love it, even though I have only seen it in reproduction. To see it alive here excites. But what of people who haven’t met Alice Neel’s work yet. They might rely on reviews. If so, if you have that opportunity go to Laura Cumming first.

When Laura Cummings reviews an art show, you might as well just reproduce her words for her approach is always focused on the right kind of knowledge, skills and values that you will need to be able to get at the art and learn to know how to love it. Her review of this new retrospective of Alice Neel, the largest to come here, is a case in point. She makes you see, even if you disagree. Look at this stunning critical paragraph – which generalises at a level that forces you to look critically and empathetically, to put your first impressions of a painter not quite anyone else in the frame of what art can do:

And it is the weird fact of our own mind-body coexistence that seems at the heart of Neel’s ungainly style. For no matter how familiar the sitters may be – painters, poets, trade unionists and intellectuals, Greenwich Villagers, Warhol’s superstars – the portraits remain outlandish. There is her trademark blue outline, looping, skimming, and scudding round each figure, that doesn’t seem bent on correctness of proportion or old-school description. The heads are always slightly too large for the bodies, the brushwork is never flattering but emphatic; here and there you are looking at garrulous caricature.[1]

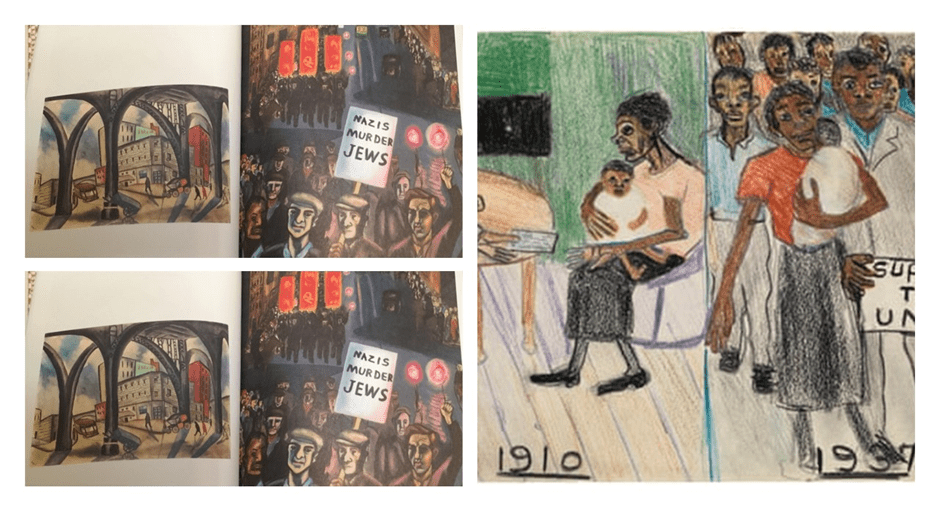

And then look at Neel’s self-portrait, which Cumming tells us, leads off this exhibition. Every element Cumming picks out is there and more. You look for the blue outline and follow the blue lines, dabs and shadows that reframe the outlines, and queer the shapes as if they were the aura of the person and her objects. Objects like that blue-striped chair, the paint-brush that crosses her body and the loosely held handkerchief. It is as if flesh and personality colour stained the background as a leakage from her very being, flowing out in the shape of the penumbra of the woman and her chair. Shape is everything and nothing, meaningful and yet not. I find the word ‘caricature’ used by Cumming though a little uncomfortable, but you know what she means even at the moment you feel like insisting that there is so much more than caricature here – a kind of getting at the truth of a person that is not concentrated on exaggerations of outward features but instead on getting at what such features might mean in terms of the interaction between viewer and viewed that produces emotion and meaning – deeply emotionally charged cognition you might call it.

Superlative defiance’: Self-portrait, 1980 by Alice Neel. © The Estate of Alice Neel in : https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/feb/19/alice-neel-hot-off-the-griddle-barbican-art-gallery-london-review-action-gesture-paint-women-artists-and-global-abstraction-1940-70-whitechapel-gallery

You can’t help noticing Alice’s feet that seem to hover over her background, emphasising that the cusp between horizontal floor and vertical wall is deeply queered. The motility and lightness in her feet defy the telling gravity of flesh in the feel of her belly and breasts bearing downwards. It is as if aging itself were being taken apart conceptually as a thing made up of viscerally physical and psychological factors. Caricature does not suggest that grasp of inner truths – belonging to both and neither the sitter nor viewer but existing as the meaning of what we call life.

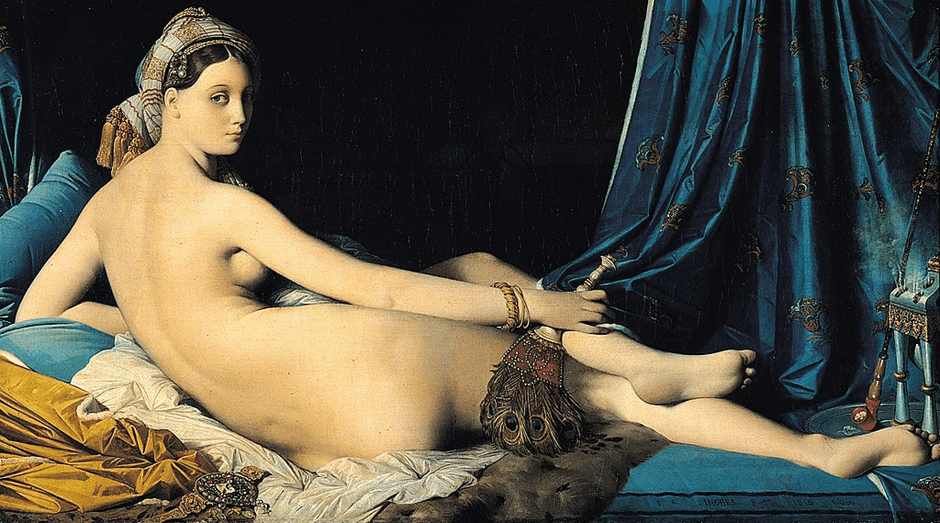

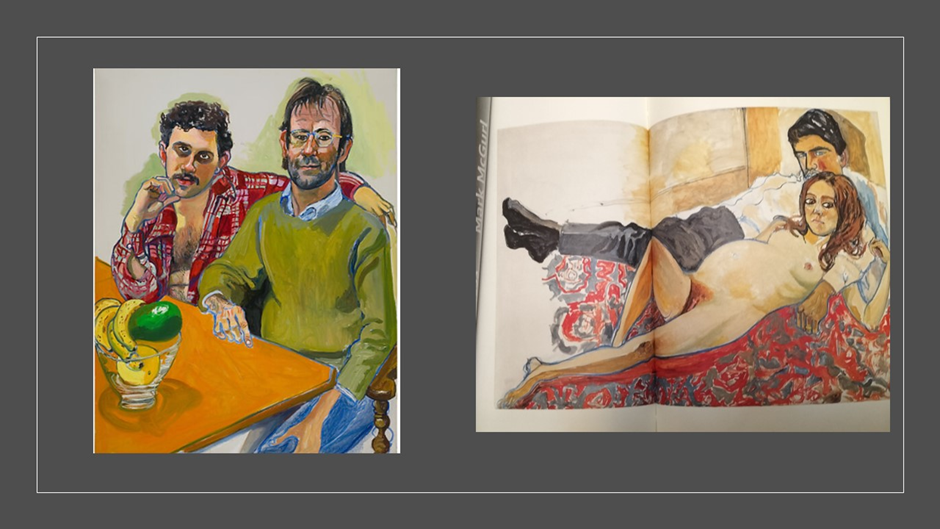

I call it cognitive because there is a determination not only to show what Alice sees but what she thinks that we all should see too in order to really know the world we live in. To her all solid things sustain in their surrounds a perpetual intellectual commentary on the world of inequalities that operates even at the most basic of our senses and appeals to our sense of the attractive or beautiful or repellent and ugly and sometimes all four of these at once. Male artists have used the odalisque to turn women’s bodies into the subject and object of art – to become as it were the means of a male artist’s projection into desired prominence as an artist and as a man, appealed to by the insistent gaze of the woman in the picture, looking directly at us, as in Ingres classic example, Grande Odalisque.

Grande Odalisque By Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres – wartburg.edu, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5334530

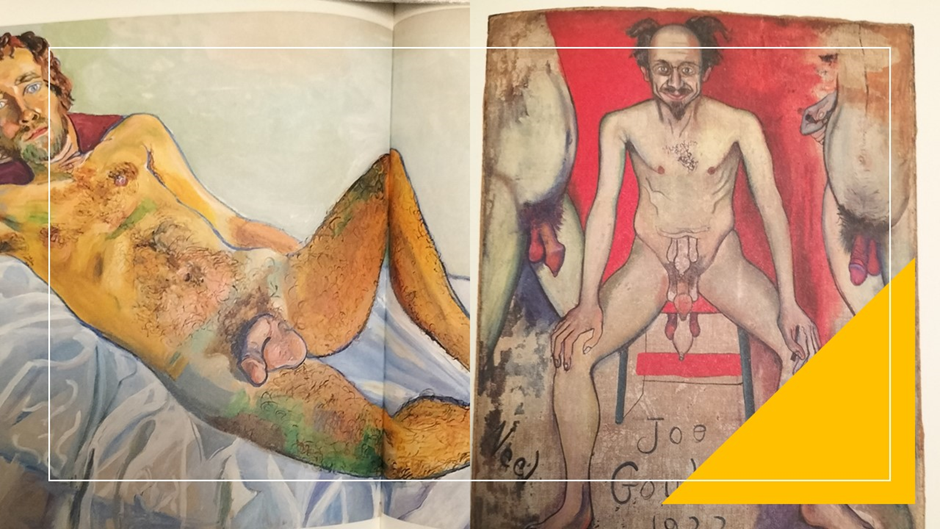

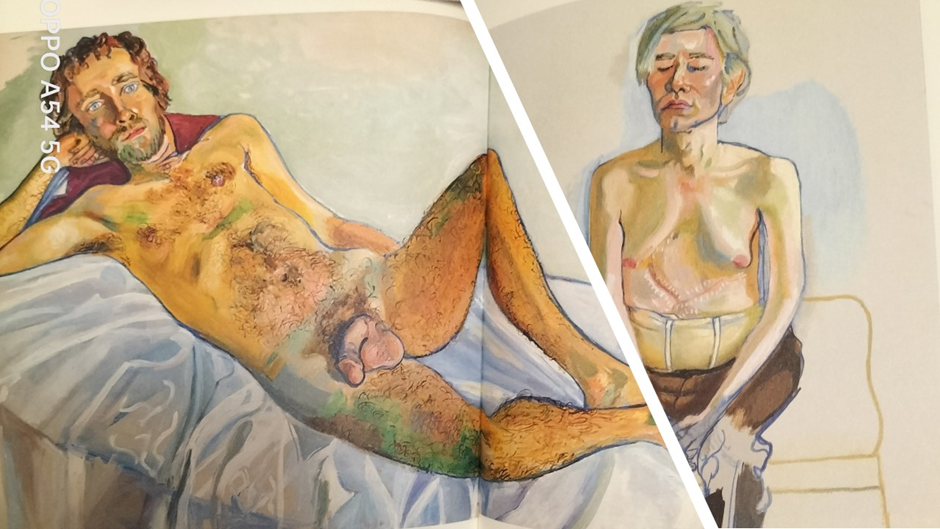

Ingres wants the sensual appeal to glorify himself; to tempt us to see his glory in the making of flesh that appeals and confirms the power and command of the desire of the viewer, we need to see everything here as making an appeal to us. But not so, says Cumming, in Alice Neel, who painted John Perreault in this mode in 1972. Eleanor Nairne tells us in the show’s catalogue, that the art critic and curator was persuaded to sit for a painting in this form as a condition of allowing him to exhibit her painting of Marxist Joe Gould (turned into a conceptual icon of a phallic God with a range of penises on show) as the curator of a show of male nudes.

Part of the condition was that the Perreault’s painted odalisque would also be in “the show he’s curating”, in Neel’s own words.[2] Cumming sees the cognitive bent behind this:

Face versus body, the mind in spite of the physique, or perhaps the life itself: that seems a steady fascination. The art critic lies back, voluntarily naked, in the thick pelt of his own body hair: an ape of an odalisque. …

To call Perreault the ‘ape of the odalisque’ is funny in so many ways when we think of the sexual appeal (not universal I believe nevertheless) of nude hairy males. But the important thing is that we cannot see Perreault except through the idea he imitates. Of course there is the same loopy blue line and the caricature of form but there is also a new sensuality that aligns itself with the blue stains of the crumpled sheets on which he lies and gazes at us, cooperating in placing his penis centre-stage. Men who do this, oft her husbands and male partners, got their penises somewhat mangled, and indeed caricatured, in her paintings, such as Carlos Enriquez whose penis is turned into a tired stamen in Bronx Bacchus of 1929, John Rothschild’s penis is being aimlessly self-caressed as he pees into a sink in 1935, or the more beautiful Kenneth Doolittle whose sleeping self has his penis angled to contrast with a hanging crucifix with a modestly draped and feminine Christ above him. The longer you look however, the less comfortable or inviting looks Perreault’s face. It does not bring you in as Ingres Grande Odalisque or Manet’s Olympia does.

It is a point even more emphasised in the portrait of Warhol of which only a small part is above. For Warhol has shut his eyes to the devastation of his body following an operation. Cumming puts it thus of what this tells us about Neel:

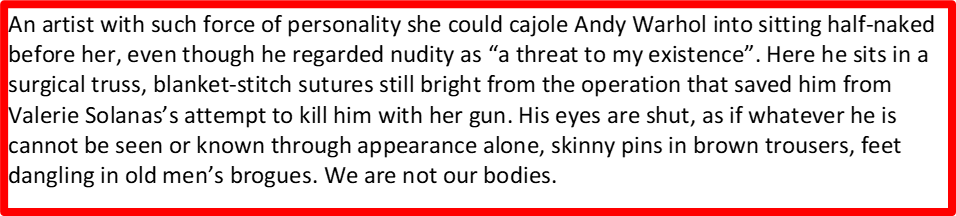

This is magnificent art criticism such as we expect from Cumming. But Cumming is deeply sympathetic, as we are told by her is this show too, to a ‘wider and more political view of Neel’ than most people in the art world, who now grudgingly rate her, do. And that means honouring the woman who is described in her FBI report (reproduced in the catalogue) as ‘sympathetic to the Communists and associated with a number of Communists’.[3] She was a Communist, of course, and painted to show her admiration of workers dominated by, but yet to inherit,dour cityscapes, the benefits of trades unions and the common humanities supported (then) by the American Communist party as in the early ‘cartoon’ like drawings below from the show. Her humanity shows even better when we are told that she hated Party meetings because of the bureaucracy involved.[4]

Cityscape 1933, Nazis Murder Jews 1936 & Support the Union, 1937 by Alice Neel, ‘a lifelong feminist, humanitarian, activist and braveheart’.

It is an art and a politics in interaction we see here focused on the common ground of the reality of human life – the sustaining of the body (including the social body) as important as that of the spirit. As Cumming tells us (it is in Nairne’s catalogue essay too): ‘Neel painted right up to her death and was known to phone friends to exclaim: “Guess what, I’m still alive!”’ In the process she mixed with radicals including queer radicals like Andy Warhol and Alan Ginsberg:

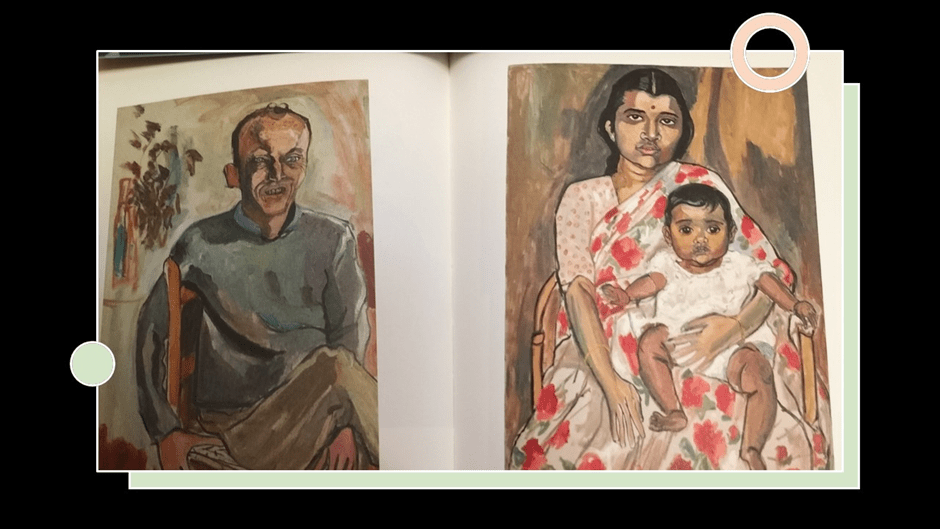

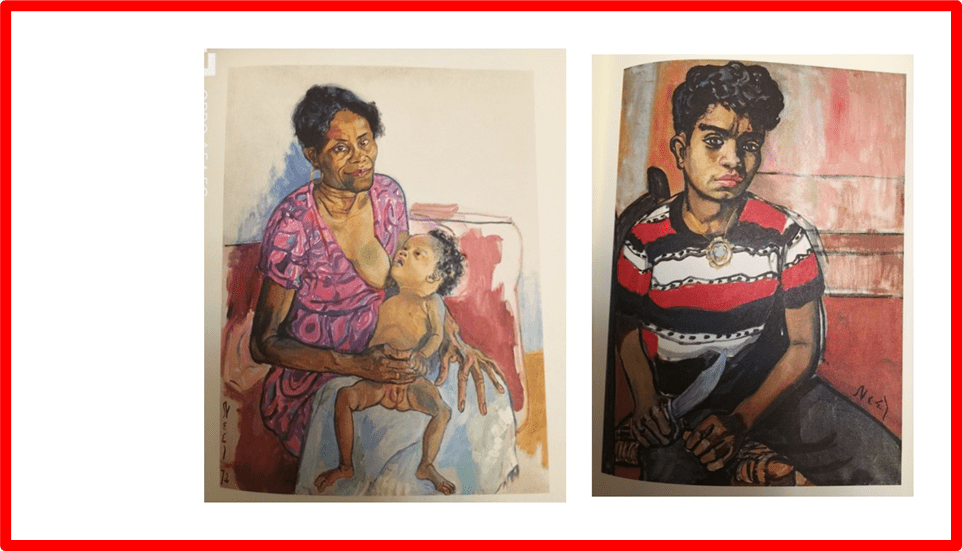

Yet her humanity was the same whether she painted the famous queer poet Frank O’Hara (1960) or an anonymous Mother and Child (1962), one of her many Madonnas for the people, where the sitter is from a marginalised ethnic minority in 1960s USA. But even queer poetry and poets were marginalised. Nairne tells us that it was vitally part of Neel’s mission to redeem the human figure, as truthfully in its essentials – biologically physical and psychosocially accurate – as one could and to honour persons regardless of the social barriers put between them by hierarchical social structures that feed ‘racism, homophobia and poverty’. She wanted them all to be given ‘the nobility associated with the history of portrait painting’ at its best.

She drew attention to the boundaries of figures (as either liminal, as with O’Hara, or faintly and fragilely defined in blue as in the Madonna above). Nairne also says this showed ‘the porousness of human boundaries’ and the dynamic actions by which a person ‘becomes’ a person in interaction with environments and others, presenting ‘our edges as a space of becoming’; a ‘political act’ citing analogues in phenomenology such as the thought of Merleau-Ponty.[5] Neel believing she was painting power differences both in the interactions of grouped sitters and within the formation of the what we call the ‘character’ of the person: Neel elaborated it as ‘all their character and social standing – what the world has done to them and their retaliation’[6]. Relationships could appear positive, negative, or more usually a fractured combination of both, in her couples. These are not easy to interpret, and she saw them in couples of any combination or relationship type. For Neel her ’primary motive .. was to reveal the inequalities and pressures as shown in the psychology of the people I painted’.[7]

It feels easier to see patriarchy in many levels in the male and female scenario above than the male and male one, but they are there nevertheless, if encoded less obviously than in the use of the odalisque pose for instance for the pregnant woman and the confident rather possessive aggression to the viewer in Algis in Pregnant Julie and Algis 1967. And, in individuals, power lies not only in internal features that relate two sitters but in the interaction of gaze between individual and viewer. Neel could persuade sitters to expose themselves as they had never done or would hope they ever would. Some hated that later in their lives, including her children sometimes, feeling exposed beyond what is bearable to our need to control our self-representation. We know Carmen in Carmen and Judy (1972) below more than we know Carmen would want us to know her in many ways. Nevertheless, the oppression she has endured as a black working-class mother is balanced by the trust which allows her to expose her breast in an act of feeding her child, whose genitals are exposed. It is a beautiful painting but not comfortable. Likewise Georgie Arce No. 2. (1995) shows a person bearing a vicious knife that might be pointed to the viewer that defends themselves as well as exposing themselves. This painting, so masculine in tone, feels to me though one of the most hermaphrodite pictures I have seen. It is incomprehensible at the same time as being lucid about sex/gender.

I cannot wait to see these and other paintings in the flesh. I am keen to hear Justin’s take on them, though he has committed himself to no more than to say their portrayal is truly ‘brutal’ (not a word he uses without nuance). There is much to see. The catalogue though deserves a mention. Made to be easily held in the hand and readable, it emphasises themes in the knowing of persons more than anything else. It is truly remarkable. If you can’t see the show, get the book.

C.P. Taylor’s Good livestreamed from London’s Harold Pinter Theatre to The Gala Theatre, Durham (and nationwide various venues) with reference to text: C.P. Taylor Good (2022, first produced by the RSC in 1981) London, New York, New Delhi & Sydney, Methuen Drama.

I had not heard of C.P. Taylor before booking for this live-streaming and hence I prepared by reading the play and reviews with a fresh eye and with few expectations. As for this production, much in it is deliberately shadowy I am told, so more of this later. First played by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1981 it was revived in 2022 with the present cast, although the cast is, I think, much reduced in the version of the production we will see (if Arifa Akbar’s review in The Guardian of 13 Oct 2022 is of the present state of the production, the cast has been reduced to only 3 of its original number of 11).[8] David Tennant plays the main role, a German professor of German literature, Halder – a man on stage all of the time and who may have generated as products of his own thinking and memories some of the characters and scenes and other phenomena, such as a rendering of some conversations as in a musical film. The rest of the roles are divided between Elliot Levey and Sharon Small. If so, Small plays Halder’s mother in the last stages of dementia, his wife Helen whose character is entirely dysfunctional and his young and besotted student lover, Anna, whom Halder treats most often as a necessity to stay his aging, it seems. Indeed Andrzej Lukowski in Time Out says the fate of both subsidiary characters is to play mainly the foils of Halder’s ability to access the same means to power unavailable to them: ‘vulnerable people who lack John’s ability – privilege, I suppose – to simply blend in with Germany’s queasily lurching society’.[9]

The actors

Elliot Levey, for instance, plays, amongst other roles, Fascists who themselves seem subjected to rather than choosing fascism, even Hitler (in my reading of the play) – for after all these characters may be just projections of Halder’s neuroses. Levey is also the Jewish analyst, Maurice, hoist on the horns of his own Unconscious, and so easily betrayed by Halder, who is, at other moments ready to profess love to him too. In fact Halder’s love always prevaricates. He says, for instance, (‘to himself’ we are told): ‘He’s a nice man. I love him. But I cannot get involved with his problems’.[10]

Akbar speaks of how the play is often interpreted as ‘an examination of how a “good” man is corrupted’ but queries that reading precisely because a main agent of that corruption is the refusal ‘to be involved’ to do good, for ‘he is not simply following orders: he is an active participant in the’ Nazi Party’. Indeed good is a word that seems mainly to bear the meaning of benefit in the sense she uses it in the following: ‘The good of the title, is not, as we assume, referring to a good man turned bad, but a man who turns bad because he serves his own good above all else. “If I am not for myself, then who is for me?” he says, …’.[11] To Lukowski, the play is obviously a study of ‘human evil’ and is, for David Tennant, one of the many such roles he has played after abandoning the dully ‘good’ Doctor Who.[12] Both critics agree evil is brought, about by apathy and indifference to the fate of others who are not directly our responsibility as such.

In Act Two he tries to work out if the fate of Jews matters to him at all:

I have got a whole scale of things that could worry me … The Jews and their problems … Yes, they are on it … but very far down, for Christ’s sake … Way down the scale. That’s not so good, the Jews being so low down on my anxiety scale.[13]

The placing of the word ‘good’ here shows it’s performing a balancing act between both meanings – what is absolute ‘good’ and what is the thing that is ‘good for me’ or even what I think is ‘good for’ the other person. This is how one decides about euthanasia as an option for one’s own mother, he finds, so why not, the Nazis think who read his novel on the matter, the way we decide about the fate of the mentally ill, learning disabled, ‘homosexuals’ and, after all them becoming the ‘Final Solution’ for the problem ‘of the Jews’. That means the play is chilling for it evades the notion of active evil as an explanation for the Holocaust where human apathy and indifference serves the explanatory purpose on its own. In his Preface, C.P. Taylor says even ‘criminal’ is too easy a word to use of the ‘Auschwitzes we are all perpetuating today’, because:

my concept of history … is not quite simple enough to allow me to see either the anti-social activities of the Third Reich, or of the West today, as simply criminal. If the problem were so simple, the solution might then be equally so.

Even more puzzling, especially if you have read the play as I just have is Taylor’s insistence that his play, however dark and narrow morally as well as in its literal dramatic setting in this production it would seem to be from the reviews, is a ‘comedy, or musical-comedy’.[14] Indeed Halder seems to think that his flaw is that he is a character in such a genre of popular drama.

‘… however dark and narrow morally as well as in its literal dramatic setting in this production it would seem to be from the reviews, is a ‘comedy, or musical-comedy’. The play, set and dark shadows.

He continually hears unreal music from musical bands that get projected into his stage and mental environment: ‘I can’t lose myself in people or situations. Everything’s acted out against this bloody musical background’. His mind, full of musical theatre of different kinds, appears to project this fullness onto the world as a play-with-a-play. … The whole of my life is a performance?’ [15] Inside the Nazi’s headquarters he sees it, and indeed it is suddenly sung as if it were, “The Student Prince”: ‘Major: (singing to the tune of “The Drinking Song” from “The Student Prince”): Drink, drink, drink, / To eyes that are bright / …’.[16] To Eichmann, who appears in the play and who is the supposed author of The Final Solution, the Nazis need Halder to lend the humanity of literary studies, and its moral pragmatism of accepting a totally faulted humanity, in order to justify themselves – and this explains the use of musical bands to play ‘a Schubert March’ to the soon-to-deceased into the gas ovens of the concentration camps.[17] (This seems to be something we will only understand when we see the play staged). It needs to be seen then: Eichmann says to Halder, ‘I want the same human, without sentimentality approach that seems to be your particular strength …’.[18]

I want to watch this play very much but it ain’t gonna be an easy watch.

All the best

Steve

[1] Laura Cumming (2023) ‘Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle; Action, Gesture, Paint – review’ in The Observer (Sun 19 Feb 2023 13.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/feb/19/alice-neel-hot-off-the-griddle-barbican-art-gallery-london-review-action-gesture-paint-women-artists-and-global-abstraction-1940-70-whitechapel-gallery

[2] Eleanor Nairne (2023: 26) ‘The Toucher Touching Touched’ in Will Gompertz & Eleanor Nairne (Eds.) Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Munich, London & New York, Prestel-Verlag, 19 – 27.

[3] Reproduced in Gompertz & Nairne op.cit: 7.

[4] Ibid: 119

[5] Nairne op cit: 20 – 23.

[6] Cited Nairne & Gompertz op.cit: 96.

[7] Cited ibid: 109.

[8] Arifa Akbar(2022)’Good review’ in The Guardian (Thu 13 Oct 2022 11.55 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/oct/13/good-review-harold-pinter-theatre-london-david-tennant-cp-taylor

[9] Andrzej Lukowski (2022) ‘David Tennant is a chilling moral void in CP Taylor’s powerful Third Reich drama’ in Time Out (Thursday 24 November 2022) Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/good-review

[10] Halder Act 1 of C.P. Taylor Good (2022: 21, first produced by the RSC in 1981) London, New York, New Delhi & Sydney, Methuen Drama.

[11] Akbar, op.cit.

[12] Lukowski, op.cit.

[13] Halder cited Good, op.cit: 91.

[14] Ibid: 10

[15] Halder cited ibid: 19.

[16] Major cited ibid: 50f.

[17] Ibid: 107

[18] Ibid: 99

3 thoughts on “NEW EVENTS to ‘A Preview of the Highlights on my visit with Justin to London from Monday 17th – Wednesday 19th April 2023’: Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle at The Barbican 19th April (1100) and a streamed event on return (20th April – Good C. P. Taylor live-streamed from Harold Pinter Theatre!”