‘Even now, depending on the situation and who I’m with, an infinite number of adjustments, changes and corrections occur in my body. I recalibrate my movements, my thoughts, my words, my accent; I switch roles to be the masculine working-class boy that I was supposed to be’.[1] This blog is about the personal challenges posed to me by Michael Hendrick’s (2022) Difference Is Born on the Lips: Reflections on Sexuality, Stigma and Society Cheltenham, FLINT.

This is not a review of Michael Handrick’s book but rather a response to it’s closing invitation to ‘to speak your truth’ since ‘it’s our time to make a difference’.[2] I still wondered whether I could allow the boy inside me, a decidedly frightened white cis queer working-class boy from a council estate in West Yorkshire to speak through the layers of my own aging. Age creates its own set of differences including, as with Michael, various rites of passage through mental illness (at one time severe and with a capacity left in it to make its personae present themselves again) and the desire to keep silent is in me too.

There feels danger in speaking out from the core. But one factor in that is that the over-opinionated adult selves I bear don’t always find themselves thinking Michael has got it right as he translates his life situations into theory and sometimes starts from theory in order to use his life as its illustration. The theories range from knowledges about developmental and social psychology, mental health and even biology, which he sometimes uses as cited by unnamed (in the text) authorities for his conclusions (referencing them only in endnotes attached to number codes in the text) and sometimes as metaphor. Biological neuroscience is often invoked as metaphor – maybe inevitably when the realm of thoughts, feelings and actions is often referred directly to in popular culture as the product of specific neurotransmitters at the synapses of the chains of communication in the central nervous system. At another point the science of homeostasis is invoked to defeat the locked systems of binary thinking.[3] I part company with some of the submerged theory but not all and that isn’t the point of the book. However, I am in particular still working on whether I think the stress in the book on the theory of ‘trauma-bonding’ can be read as straightforwardly as Michael seems to read it or applied as widely as he applies it. As a theory, I guess I see it as much less conclusive or comprehensive about the interaction of power, desire and emotional attachment than it seeks to be.

But so be it, for Michael Handrick does not set out to be primarily a theorist in relationship development and phenomena. Moreover, he allows for contradictions in the theory he uses, as I think we must. In brief and with no intention to follow this up, my feeling is that the book needs to say more about how the abuser becomes such and who are, and why are they such, the people who accept that some forms of behaviour perceived as abuse will persist within relational dynamics between persons. These are the people that from whom he sought ‘advice and support’ and who said:

‘It’s attention-seeking, weak, always looking for drama. It’s not as bad as it seems. He means no harm. I don’t want to hear about it. Doesn’t sound like anything worse than I’ve heard before.[4]

Michael says of those unnamed others (whether they were they ‘professionals’ or friends for instance might matter) that their ‘response was not okay and is one of the reasons why so many men don’t come forward or realise themselves what they’re going through’. That is quite a blaming attitude and, without context, sits uneasily with me. This is so, especially because I suspect Michael would trace those phenomena, in the final analysis, to structural issues in the social order and to ideologies, notably heteronormative and gender-binary prescriptions of social relationships. But these final responsibilities for inadequate folk theories and the behaviour of those who propound them are more suggested than discussed. And thus what there remains in the book is a kind of blaming of collusive personalities that feels counter to what it could achieve given the values of social progression to love and free bonding in ‘chosen families’ that that it seems to prefer.

Because I think it relates to issues in the expression of my own response to past trauma I wanted to pick out though one instance where Michael exemplifies concrete aspects of abusiveness in male to male relationships in his book, one where precisely people might say to him that what he suffers is greater than the offence he sees warrants and where some may struggle to find any offence at all. I think I have identified in myself some correspondent structures of feeling, related to social media communications, wherein triggers exist to find cause for accusation that the other in a particular communication is neglecting, slighting or just being ‘too busy’ for you in ways that one reads as lowering one’s priority in their eyes. The instance is here:

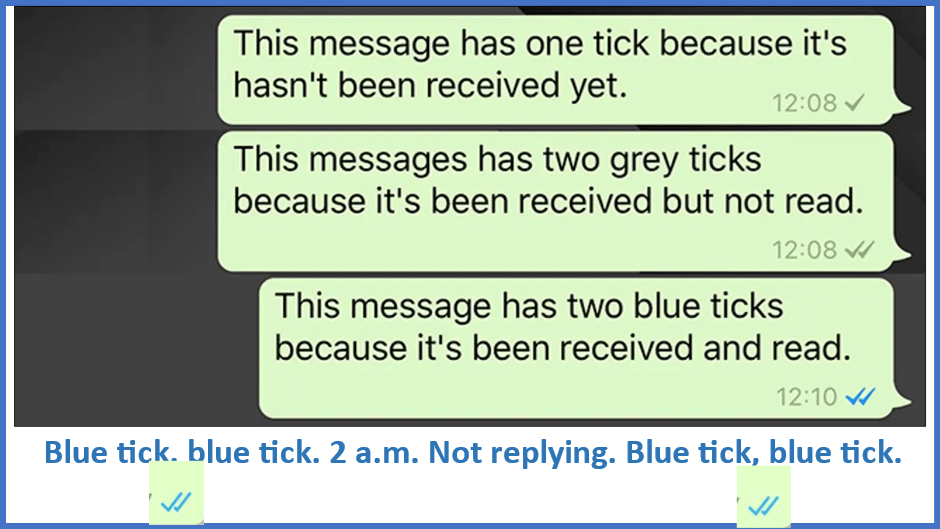

Shouldn’t have worn the blue shirt. Shouldn’t have trimmed my beard. Invited me over. Hasn’t replied all evening. Message read, not replied. He needs me, come here. Blue tick, blue tick. 2 a.m. Not replying. Blue tick, blue tick. It was dark. It was raining. The door was locked. Message received, It’s your fault, Michael.[5]

It’s a kind of collage of moments of self-blaming for problems in a supposedly loving sexual relationship where the supposedly beloved finds reasons, even in their choices about minor changes in their appearance, for a lesser response from the other than expected. But even here it is not clear whether the italicised, ‘It’s your fault, Michael’ are words said to him or intuited from silent messages requiring interpretation such as confronting a ‘locked door’ after a miserable trip to his home or by unexplained gaps in a What’sApp communication.

The cynic in me (who is, as Michael suggests partly a by-product of trauma) thinks that some modes of communication engender anxieties that cannot be resolved and may be as much to do with the novel forms of expectations for immediacy of response to messages generated by the capacity of digital communication to force us to be there with minimal time space for either reflection or second thoughts) . In What’sApp, the status of a message is visible (though I am told this feature can be disabled – I haven’t tried it) and hence one can know if the receipient has received your message and not read it or received it and read it but has not replied. This is the space opened up for anxiety in Michael Hendrick in the piece above, illustrated (for those who don’t know What’sApp) below.

The space between two blue ticks, that is, becomes one piece of ‘evidence’, inconclusive in itself, of what he sees as an abusive relationship. For ‘Blue tick. blue tick’ is a sign a message has been potentially actively ignored or rejected, although, of course the correspondent might have had many reasons for not responding that do not relate to or intend harm, even though harm is caused. In such instances one can have reason for thinking it’s your own fault for over-interpreting signals and /or being being too sensitive to them because their significance is less than one infers. After all does not trauma cause people to predict rejection they fear and perhaps even cause it to be a self-fulfilling prophesy

This scenario occurs in Chapter 11 of Michael Hendrick’s book, a chapter dealing most of all with abusive encounters in male gay relationships, and where the abuse, it would seem, is one way, directed at Michael, and the blame for that abuse projected onto him by the abuser:

I had opened up myself to be vulnerable, to allow myself to trust in someone else, to put my hopes in someone else. I was giving myself to them, in part, as resignation of knowing that the person I truly desired would never come. There was a sense of inevitability to it all.[6]

Of course, Michael clearly shows here that the agency in creating the opportunity to be abused did lay in him primarily for he is the subject and object of the transitive verbs here: ‘he’ opened up ‘himself’. He was giving up himself. He does so, he insists because this was the only pattern of relationship he knew from his past, since: ‘Trauma and abuse stay with us, it can alter the way we think, how our bodies work, how we respond to situations, how we interact with people’.[7] If this is so, it is easy to see that the person one becomes can act in faulty ways in relationships, even in overinterpreting social media phenomena as signals that they were not so to others, even their ‘author’. Over and above this heteronormative social myths, of the fairy tale ending of stories in the arms of a handsome Prince for instance, supervene if persons are not educated to the rights of all living things to self-assessed security and active ongoing choices between those things that meet our legitimate needs as those needs change, as inevitably they do.

That’s why Section 28 was so heinous, ‘a silent killer’, Michael tells us: citing Thatcher’s clear identification of her ideological enemy as the teaching in schools that a person has, in her own words, an “inalienable right to be gay”. He does this to prove, if proof were needed, that the state in the eyes of some has a right to prescribe sexual choice and ensure that LGBTQ+ communities get the message that they ‘don’t belong in this society’.[8] The same is happening at this moment in the hounding out of office of Nicola Sturgeon, one of the finest politicians of our era. But for me what grabs my attention in this book is the attempt to look at the ways in which the expression of our sexualities, in perhaps different forms in different times or as a unchanging characteristic, intersects with the marginalisation of working-class identities, values or even stories of origin in modern capitalist societies. In this I sense some debt to Owen Jones’ seminal work on the ‘demonization of the working-class’ as Chavs, though that work is now so much part of the intellectual ether that I think any influence will be indirect. However, with Michael’s account of response to working-class communities my own feelings and thoughts fall much more at a distance. With one part at least I sense a commonality though. Michael Hendricks speaks about a difference in attitude to education and work in the interests of education that characterised himself as a working-class boy from those of his middle-class peers. Avoiding his local comprehensive by choosing instead ‘the former grammar school in the town’, with ‘two sites and centuries of history’, his experience mirrored mine of travelling further to the grammar school, to which to which entry was in 1965 selective (but not by examination at age 11 – the dreaded ‘Eleven-Plus’ – for this was Alec Clegg’s West Yorkshire).

The council estate I lived in was some 7 miles away, though adjacent to the alternative secondary modern school. This meant that, travel by whichever bus I might, I could not escape large groups of young people travelling away from the secondary modern to its wide rural catchment by bus. Nightly at the age 12, I was exposed to large groups of people, most humiliating when it was the older girls, who chased me shouting ‘keg him’ (take his trousers off) and more often than not they succeeded. Getting home was a worst nightmare, unless I did not tell the truth that this done by other people for on our estate all one knew for certain that you had to ‘stand up for yourself’. Michael says, in his book, that taught him ‘to be tenacious and resilient’:

To fight for myself, to defend myself. It taught me the value of family and friends, and to fight for them. It taught me hard work for everything because nothing was ever going to be given to me.

Reading this I remember from my own experience only fear and cringe a little at Michael’s confident assertions of benefit, as I have from Owen Jones’ similar experience. I was not a tough kid I think and though I learned the necessity of hard, obsessively hard perhaps, work at school, I did not ever develop a need to build my body into physical strength. Michael did this using athletics, a means of developing strength considered in his school as somewhat the recourse of what Boris Johnson calls the ‘girly swot’(in 2019) aiming his remark at David Cameron. Even when I took up exercise in my late 60s last year, my core muscles were still clearly absent, a long sacrifice to sedentary work and reading that took me through 4 grade A A-levels, and two first class honours degrees as well as various professional qualifications (in social work , counselling, mental health work). Even in my council estate (we eventually moved to a council estate nearer the grammar school). But reading Michael’s words about his gratitude for learning tenacity and resilience makes me still shiver, feel the driving lack of self-worth that he finds motivated outside of his origins on the estate, which he paints as being on the whole more supportive than otherwise, despite the attitude of boys who latched onto the distaste for the ‘gay’ (with its range of meanings touching on the inadequacy of ‘girlish’ boys) which ran through school cultures of his day.

Here is a difference then still ‘born on the lips’ and, in some ways, Michael’s mouthing of that difference from his perspective hursts somewhat. This is why I think I stand apart from him on the blame he sometimes points at those who unintentionally hurt one, and stand shy of seeing the apparent microaggressions, for that they feel to him to be. But perhaps they are not microaggressions at all but rather based on the fact that we are all ignorant of each other’s triggers to pain. Indeed, I think Michael in fact is more ambivalent about his working class origin-story than he seems in the overt statements I quote from him above. For his choice of a former grammar is described as having ‘escaped the kids on the estate’, even though carrying with him that ‘tenacity and resilience’ learnt from them. Nevertheless those latter qualities only matter because he needs them to survive that school in which it was ‘clear he didn’t belong’. His privileged peers in the school did not need tenacity or resilience so much because though there ‘were no different to me or the kids on the estate’, the ‘difference was the world had told them they were better’. This systematic and structural difference proceeding from mechanisms of accidental class placement gives ‘an easiness’, a ‘privilege, they belonged, it all can naturally to them’.

As a result they found Michael’s ‘hard work’ at aiming for success incomprehensible, whilst to him the reason for working hard is obvious, it is precisely because he lacked reassurance from external factors and hence: ‘I had to to work ten times harder. There was no room for error’.[9] All this I recognise in my younger self between 1965 and 1971, though it tended the further to isolate me from people at school, the council estate and even, I think, my family, which is clearly not the case for Michael. Indeed I remember working class family as riven with conflict – there was no natural reliance on ‘meritocracy’ then, for I would say that this concept was still suspect to the working class, associated in working class literature with schemers and traitors to some extent: in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Room at the Top and A Kind of Loving.

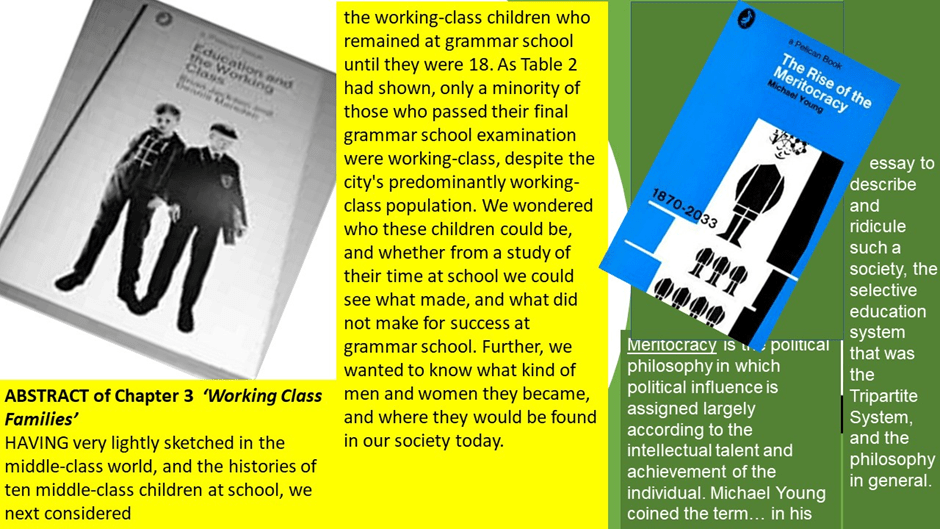

The books I used most in my S level in General Studies were Michael Young’s The Rise of the Meritocracy (recommended by my English teacher who idealised the then Marxist Leavisite critic Raymond Williams) and Brian Jackson & Dennis Marsden’s Education and the Working Class. The latter helped me to see the difference between working class and middle-class domesticity of the period, even down to the sparcity of homework space, and fuelled the sense of exclusion, for this study of grammar schools used the catchment areas in which I lived to show how few working class children got to and survived the system. The latter book insisted that what we know as ‘meritocracy’ (as raised to a principle in education by Tony Blair, and later by Theresa May) in more recent times was by Young considered a means of maintaining divisions in society and promoting elite classes whose role would be to ensure that differences of access to opportunity (for educational excellence, job roles and goods) were maintained, if not now solely by a principle of direct inheritance of privilege. Both saw that individuals escaping class constriction would involve betraying those left behind in the structures that ruled over them.

Michael, born and educated in an era where meritocracy is a prominent value sees it as dominant in his vision of the working class, whereas Jackson and Marsden had stressed communalism of interest as a predominant value in the working class. To Michael in contrast his life on a council estate was ‘governed by a meritocracy. You were judged by your own abilities to hold your own and by earning your place in the hierarchy’.[10]

That was so probably after the shift in values inside a new working class that shared with Thatcherism (so much so that some in the Labour Movement called it Blatcherism) the view that structural shifts in economic circumstances could occur only at the level of the individual alone. Altogether the working class Michael knew and writes about was not the one I knew. Nevertheless, there was still stress on escape that still haunts the work of people my age, such as in Sally Wainwright’s work (born in 1963 when I was 9). Her current series on TV, Happy Valley, which deals supposedly with working class communities (although situating them supposedly on the cusp of criminal communities) in Halifax where I was born in 1954. The message of it’s theme song is unmistakable:

For, education was the only ‘escape’ from such communities, and community was heavily geographically circumscribed, defined by locality mainly and not by travel, except for labour migrations and town holidays, where everyone went to the same local holiday resort. I do remember my parents going abroad to Spain with mates from the working-men’s club but this was not an event for children. I was left in Halifax with my grandmother. Yet the desperation for escape was large, especially in women with a double imprisonment in low wage labour, if they worked, or gruelling and imprisoning domesticity. My mother sometimes resented my father for not earning enough to live more grandly and with more space and freedom, even if only for trips away. Children compound such misery in some families. And, I think I sometimes felt my mother’s anger at imprisoning her further. I find it difficult though to rehearse much of this.

However, given that these features defined working class life for me and that I felt at odds with the values of both the need to ‘fight’ for one’s survival and the masculine values attached to such fighting, I do not recognise so easily what Michael identifies as his working class life. I could not have travelled as he did alone, to Venice and thence to Florida, finding alternative social groupings defined by different values, such that after being in Florida he could make ‘a world in my own image’. For Michael, these events, ‘opened up new spaces in our minds and made safe spaces’, so that he found his ‘chosen family’ in University at Brighton.[11] My own escape occurred in going to University in London but the path to new social structures was much longer and always secondary to a heteronormative world where the men I fell in love with were usually heterosexual in self-definition, though some were flexible given the rigour of our drinking sessions. In many ways though the issue remained that of class and sexuality which stayed encased by fictional social shells in both domains, although the advent of Gay Pride did touch me in my final years in London. Some of this accounting of my different story might, but I hope it does not, sound like a claim that Michael’s situation was easier than my own. I do not believe that for a minute.

And, in self-criticism, I think that Michael has less behavioural collusion against his own working class origins than I felt bound to wear like a shell around me as I took up middle-class tastes, habits, forms of speaking and social groups. He is right that typing the working class as ‘different’, like criminals in extremes, can be done by teachers who were once identified as working class and who can talk of working-class children and families as ‘skank’, or ‘chav’.[12] Later he talks darkly about abuse based on the use of working class gay men as the source of a pleasure associated with what is pornographic (pleasure combined with ‘disgust, filth and repudiation’).[13]

However, he has enabled me to face the issue of the intersection of my sexualities with the history of class in my life, lived in the voice I use, the lexis and syntax of speech and writing, the management and presentation of body and appearance. For like him my own journey through the fictional selves generated by my life trajectory has involved ambivalent relationships with my appetites – in food, alcohol, nicotine, and sex (though in my time this seemed less an available opportunity to me at least so convinced was I of my own undersirabuility to others) – and with complications related to self-representations as masculine.

There are telling metaphors, linking to fantasies, throughot the book about eating and being eaten and the taste of flesh kissed, brushed or bitten in an over-eager kiss and myths of being absorbed by the ‘bad wolf’.[14]. He speaks later of driven behaviours:

this hunger to destroy something inside me, to destroy myself. Or fill the void inside that kept consuming and eating and remained hungry. Smoking, binge drinking, binge eating, overexercising, not exercising, the toxic relationships.[15]

And mental ill health too gets wound up in fantasies of which the most horrific are the most hidden. In London crossing Westminster Bridge, where the world opened up to William Wordsworth, at Christmas in despair about the pain of his toxic sexual relationships he sees a sight he will see forever see over again in the same place: ‘The white and red and blue and pink of London’s lights, like fairies gently drowning in the black silky Thames’.[16] Those ‘fairies’ who ‘go gently’ (too gently) in a death by drowning are the reminders to himself of the statistics for LGBTQ+ incidence of mental ill health, abuse and suicide.[17]

The beauty of this work is that it resists a merely easy take on queer relationships. In seeing the deadly dangers of hegemonic heteronormativity, it shows that homonormativity, which certainly made my life easier, can also entrap individuals. For queer individuals, whose self-expression might vary across their life, or ally them to people with different self-expression, are bound together by the root similarity of the ideologies which cause their oppression: binaries including homosexual and heterosexual, male and female. If the ‘move towards the homonormative’ has reduced ‘state-sponsored violence and discrimination’, it ‘can be viewed as problematic’ in itself.[18] It may have eradicated subcultural alliances he says and has made some LGB people antagonistic to trans men, women and identified non-binary persons. This is is a move that will in the end fall back on those same LGB people, for, as he says, ‘the same techniques’ used against them in the past ‘are now being used against our trans siblings’. Hence our ‘position in society is as perilous as ever’.[19]

More importantly, it refuses the trap of single identity politics, not just by rigorously using intersectional thinking and the differences this throws up within and across identity communities but also by insisting that identities are not only not unitary, but also not just binary. They are multiple and shifting over time and space. There are ‘different identities’ open to all of us and they needn’t compete, though it is inevitable they sometimes will.[20] The best metaphor for identity comes early in the book when Michael says ‘I have had to shapeshift, alter my skin, change my movements, morph my tongue’, oft for ill but sometimes for the good of development.[21] And the things that morph us and morph themselves are stories and stories change form all the time. There is an entire piece to write on the narrative structure of this book and its repeated wisdoms about such structures – what are beginning, middle and endings, for instance. To see them as linear and not in constant interaction is more imprisoning than any fixed hegemonic identity.

As a boy, my parents cut of my curls and put them in a box in the hope of encouraging a more masculine outcome, yet as a boy I was slight and preferred playing fantasy role-playing games to the donning of the mock military, although I remember once aping Richard III with my mock-plastic-sword. As a teenager I became fearful of being seen as feminine. I put on weight but not muscle bulk. I saw myself as ugly and unappealing to anyone, although it was to males I started building castles in the air. I would take on masculine roles really to be with them: such as working on a farm or heaving coal with a boy who had a foot in both these domains. I think I long ago buried any hint that I was not consistently interested in being and looking masculine, though stopping short of taking up football. The way forward, the escape was books and Michael too talks intersting about this root of escape, but I never found then what he found, a developed queer literature through which he ‘started to understand that there is a shared thread used repeatedly to the detriment of the working-class community’. As a result I have not yet worked through my own problems with the intersection of class origins and sexualities. I try now as an old man to address this, at least in exposing the way images of the working class are abused, in writers like Addington Symonds and Henry James, in artists like John Singer Sargent.

But Michael, thank you. You book has been a liberation to me whatever my quibbles.

All my love

Steve

[1] Michael Hendrick (2022: 45) Difference Is Born on the Lips: Reflections on Sexuality, Stigma and Society Cheltenham, FLINT.

[2] Ibid: 205

[3] Ibid: 177

[4] Ibid: 181

[5] ibid: 173

[6] Ibid: 180

[7] Ibid: 181

[8] Ibid: 152 & 151 respectively

[9] Ibid: 144f.

[10] Ibid: 36

[11] Ibid: 137

[12] Ibid: 35

[13] Ibid: 75

[14] See for instance ibid:19.

[15] Ibid: 165

[16] Ibid: 25

[17] For example, Ibid: 47, 182

[18] Ibid: 109

[19] Ibid: 199

[20] Ibid: 191

[21] Ibid: 10

3 thoughts on “‘Even now, depending on the situation and who I’m with, an infinite number of adjustments, changes and corrections occur in my body. I recalibrate my movements, my thoughts, my words, my accent; I switch roles to be the masculine working-class boy that I was supposed to be’. This blog is about the personal challenges posed to me by Michael Handrick’s (2022) ‘Difference Is Born on the Lips: Reflections on Sexuality, Stigma and Society’. @MichaelHandrick”