In Henry James’ Roderick Hudson, a plain but wealthy young urban American man, Rowland Mallett, uses his great fortune to nourish in Rome the talent of a potentially great sculptor, Roderick Hudson, who is also a young, beautiful, and naïve new male acquaintance from rural America. Many conversations between them sound odd out of context, such as this one: ‘“It was your originality then – to do you justice you have a great deal of a certain sort – …… You were awfully queer about it.” / “So be it!” said Rowland. “The question is, Are you not glad I was queer?”’[1] Is the oddness (indeed queerness) found here something queer, in a wider sense, readers import into readings of Henry James, or is it legitimate to find beneath their conventional surface signals of the queer in that same sense? A set of reflections based on Henry James (1875) Roderick Hudson (page references to Kindle Annotated Classic Edition (using page not location detail given therein).

When I was in the sixth form at school, great delight came from finding double entendre in classic novels. Even a great and beautiful woman friend of mind, of frightening intelligence, could find fun in a moment wherein, whilst reading Jane Austen’s Emma, the terribly rigid Mr. Knightley proposes to Emma Woodhouse in the garden of her home: ‘He had followed her into the shrubbery with no intention of trying it’, I think the phrase was. ‘It’, of course, had this inevitable meaning to the young (and I think sixth formers were ‘younger’ then – in the late 1960s – than they are now as far as sexual maturity went).[2] There are lots of such moments in Henry James. For instance here’s an instance when Rowland Mallett first encounters Rowland on the basis of a fascination created by their mutual friend, Cecilia, and after seeing an early sculpture of ‘a naked youth drinking from a gourd’.[3] Before he sees Roderick he hears his voice in another room of Cecilia’s home: ‘It was a soft and not altogether masculine organ, and was pitched on this occasion in a somewhat plaintive and pettish key’.[4] Oh, how those sixth-formers of yesteryear would have laughed at this characterisation of Roderick. Seen soon after he finds him ‘remarkably handsome’, chiselled like a sculpture himself though one in a garden about which a feminised nature plays, so that though he is a ‘fair, slim youth’ he had an air of insufficient physical substance’: ‘The features were admirably chiselled and finished, and a frank smile played over them as gracefully as a breeze among flowers’.[5]

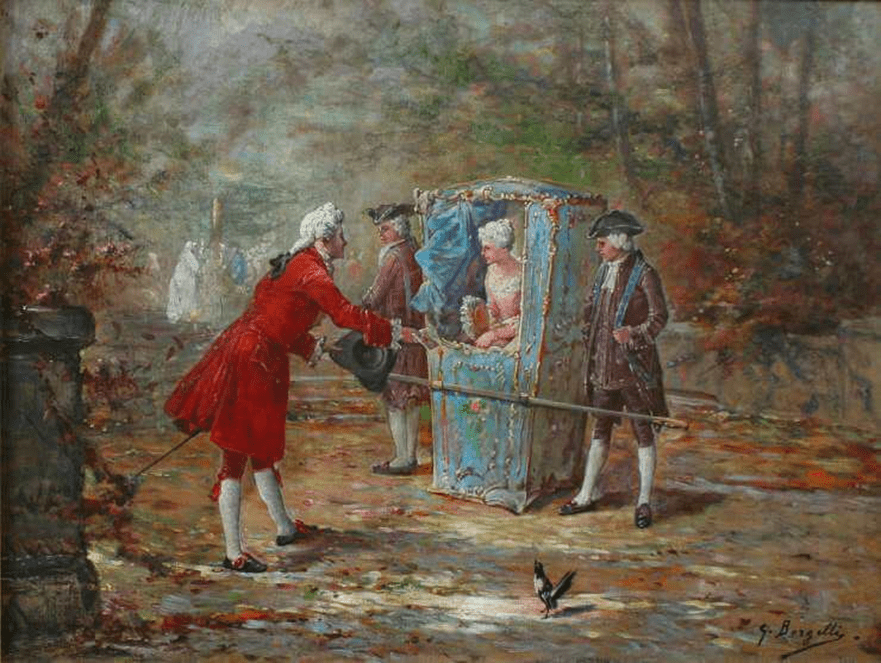

This ambivalence between masculine appearance and feminised boyish effect, we have to say, turns out to predict the character of Roderick as an older adult by the end of the novel better than other predictive hints interpreted by Rowland as those of an especial genius. His whole demeanour, until frozen in the Alps by death after a fall is that of a ‘pettish’ child, sorry for itself more than engaged in empathy or even sympathy with anyone else, as ‘feminine’ indeed as the pathetic youth, Price Casamassima , in his wife’s estimation, a man ‘carried’ up an Alp on a chaise a porteurs (a sedan chair) ‘ – like a woman’.

Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Sedan-Chair/

Now I do not wish to say that there is any virtue in reading the language attuned to this particularly highly educated late nineteenth century literary man as if it were disguised smut, I think we will ignore its means of playing with the interaction of sex/gender and sexualities at a level of coarse reading at our peril. I am not looking for unconscious readings under the text but play that occurs in the translation of registers between meanings of certain words like ‘queer’ in those different registers, none of which are authoritative (use the link for the definition in linguistics as a subject of study). The Cavaliere, or faded aristocrat, who attends on Christina Light and is attached to her mother in a way that is unarticulated, and only hinted at the end, is a ‘queer old gentleman’. The Cavaliere, in turn sees the homely mother of Roderick as a ‘queer little old woman’. For what opposes the norms of one’s own behaviour it appears is what makes something ‘queer’. In the chapter significantly called ‘Experience’ the ‘queer’ is throughout used to describe people and behaviours opposed to New World innocence: the Light family party with their poodle are all called ‘queer people’, whilst Christina Light in turn calls Roderick to Rowland ‘that queer friend of yours’.Roderick’s ‘relish for an odd flavour in his friends’ that was ‘outside of Rowland’s well-ordered circle’ is openly claimed as liking for ‘queer fish’.

Yet to Roderick the people who are ‘queer’ are those who act ethically rather than selfishly like Mary.[6] This is precisely the issue discussed in the piece I quote in my title where Rowland is considered as over-ethical in his responsibilities to his friend, Roderick’s, heterosexual object choices – between the homely New Englander, Mary Garland, to whom he is affianced before leaving America, and the elusive and apparently coquettish, Princess Christina Casamassima. Of course we need context for this word use here. Nothing is clear about the shifting objects of emotional attachment in the novel. (formerly and not irrelevantly named ‘Light’ in their first encounters). Rowland’s hidden possible love for Mary Garland is subjected to the resolution of that conundrum. In the instance at which these words occur Hudson has been, as he sees it, let down by Christina in a love tryst made in secret between them (as he sees it) so that she might marry an Italian Prince (Casamassima). Roderick has made it clear he no longer loves Mary but, as time passes, Rowland wonders whether Roderick’s affection and ties to her are being resurrected, and thus denying himself a chance of Mary for himself. Roderick however cannot understand why, if Rowland loved Mary, he should facilitate her love for Roderick. Here is the passage in more fullness; with Rowland speaking first:

‘“I admire her profoundly.”

“It was your originality then – to do you justice you have a great deal of a certain sort – to wish her happiness secured in just that fashion. Many a man would have liked better himself to make the woman he admired happy and would have welcomed her low spirits as an opening for sympathy. You were awfully queer about it.”

“So be it!” said Rowland. “The question is, Are you not glad I was queer? Are you not finding that your affection for Miss Garland has a permanent quality which you rather underestimated”’[7]

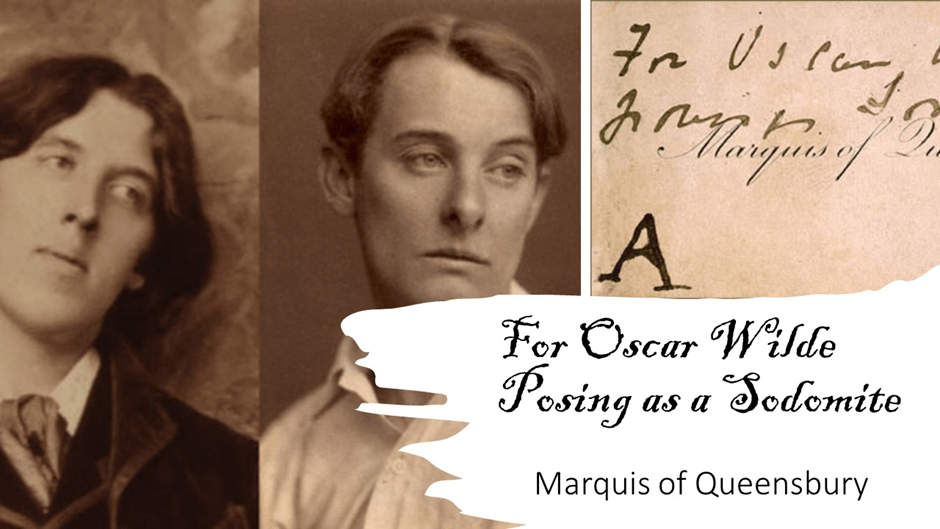

In university seminars this fuller context would be used as a reductio ad absurdum for my use of the word ‘queer’ to indicate something related to Rowland’s unarticulated sexual and romantic love, not for Mary Garland, but for the man of whom at his death the painter Sam Singleton says: ‘He was a beautiful man’.[8] But ‘queer’ is a queer word, as the article at the link here shows quite clearly. We know it was used to refer to men who had sex with men, as well as in other contexts and meanings, as early as the late nineteenth century, and could even then be used self-referentially and positively as well as negatively, depending on one’s attitude to that which stands at a distance from established norms. It was often then a matter of register and context, or assumed context since books carry assumed registers that omit direct sexual reference in the late nineteenth-century. And Roderick Hudson is an odd novel. It is like a realist social novel of manners and individual morality (in the ‘great tradition’ as identified by F.R. Leavis and sounding sometimes like a direct development from George Eliot, especially the Gwendolen sections of Daniel Deronda, as Leavis also suggests of James) but elements of this novel deliberately, in my ear at least, echo Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (especially the Alpine pursuits) and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, another story of an artist’s contact with queer doings.

And the semantics of words of depends on certainty of assumption of context. My own view is that James is quite prepared to mix contexts in such queer ways (after all is not Roderick’s state in the quotation in my collage above parodic of Satan in Book 1 of Paradise Lost ‘fallen from a great height, but singularly little disfigured’). To queer writing is to render the reference to language odd, an effect heightened by, to the conventions of reading, deliberate oddness of syntax and lexical choice. We tend to discount the registers associated with lower class or even more a social underground, but these are precisely falls of which James was determinedly aware, though he would never advertise. For ‘falls’ in this novel are threatened to pride and claims to moral autonomy and hence both Roderick and Rowland take on such hubris in seeking a flower at a great height for the lady of their apparent choice. Indeed James cleverly refers to both Rowland’s future adventure of this type on an Alpine cliff, in describing Roderick’s failure to stand up for Christina Light’s desire for a precariously placed flower in the ruins of the Coliseum:

There are chance anfractuosities of ruin in the upper portions of the Coliseum which offer a fair imitation of the rugged face of an Alpine cliff. In those days, a multitude of delicate flowers and sprays of wild herbage had found a friendly soil in the hoary crevices, and they bloomed and nodded amid the antique masonry as freely as they would have done in the virgin rock. [9]

This passage draws attention to itself by its lexis (or am I alone in having to look up and then puzzle out why the word ‘anfractuosities’ is so appropriate here) helped by photographs like those comparatives above, for James has a point about the similarity of these both natural and built faces on which an intrepid person might climb. The issue in a novel in which attitudes to nature and art are so persistently compared is surely not accidental but it also makes other comparisons the old and the young, rock touched or untouched by the human hand, the experienced and the ‘virgin’ which binary associations play with each other. And, of course, a fall is the more likely to occur where anfractuosities that offer a firm hold for the foot in appearance prove not to do in reality, and indeed, in the Alpine snow this is Roderick Hudson’s eventual fate. It is all very self-referring stuff such as scholars of Jamesian plot structures are used to finding. But it is also decidedly odd as it imagines the ‘delicate’ and ‘wild’ finding domicile in the ‘hoary’ and ‘antique’, the virgin rock being aped by human artifice. It may of course be the domestic relationship and strategy for survival for Miss Light by the crabbed Mrs Light that is being pointed to here, based in the sale of apparent ‘New World’ virginity (such as Christina may pass for) to old money (as she will inherit as Princess Casamassima). But it is locked too in human responsiveness to queer combinations, as is much else in the novel, whether in the circumstances of its European native and tourist characters or metaphor.

My point is that we can play with the reference of words by changing the register of the lexis called forth by circumstances. There are strong reasons why Roderick Hudson might be genuinely challenged by Rowland’s question: ‘Are you not glad I was queer?’ For Roderick Hudson’s opportunities in life the novel makes abundantly clear throughout stem from the fascination Rowland has for him, as a person and artist, interest that is initiated note from that statue already mentioned of ‘a naked youth drinking from a gourd’ inscribed by the word (in Greek) δίψας, (Thirst or Thirsty).[10]

James may stress the aesthetic characteristic of Rowland and his desire to know ‘genius’ in action, but there is nevertheless a curiosity in his quizzing Roderick about the statue that feels over the top and shifts register quickly from the aesthetic to the appetitive:

“Does he represent an idea? Is he a symbol?”

Hudson raised his eyebrows and gently scratched his head. “Why, he’s youth, you know; he’s innocence, he’s health, he’s strength, he’s curiosity. Yes, he’s a good many things.”

“And is the cup also a symbol?”

“The cup is knowledge, pleasure, experience. Anything of that kind!”

“Well, he’s guzzling in earnest,” said Rowland.

Hudson gave a vigorous nod. “Aye, poor fellow, he’s thirsty!” …

As Hudson bounds off here, no-one queries what the meaning of ‘thirst’ may be though its use in sexual contexts is attested from medieval times (1200 is first recorded in the Online Etymology Dictionary) and innocence seeking experience might have been a paradigm in Blakes Songs of Innocence and Experience. The real dynamic of this conversation is in the play with register, as a conversation about iconography becomes openly about the joys of appetite of, or for, youth, pleasure and innocence. You do not have to be sexually queer I believe to see the passage of desire, for instance, in this passage where Rowland listens intently to Roderick talking about his observation of other young male bodies:

,,, he gave with great felicity and gusto an account of the annual boat-race between Harvard and Yale, which he had lately witnessed at Worcester. He Had looked at the straining oarsmen and the swaying crowd with the eye of a sculptor. Rowland was a good deal amused and not a little interested.[11]

Rowlands amusement and interest can’t be pinned down though his friend Cecilia attributes it the fact that Roderick is ‘too delicious’. Sexualised or not the dynamic of one man responding to the energy of another’s ‘felicity and gusto’ is barely explained by an interest in the processes by which a sculptor seeks inspiration. There is much unsaid for me that nevertheless is urgent in my reading here, as often with Henry James’s repressed prose. If you want more of the like, consider this, as Rowland examines more of Roderick’s art, including ‘rough studies of the nude, and two or three figures of a fanciful kind’, wherein Rowland finds ‘effort’ that ‘needed only to let itself go to compass great things’:

Rowland turned to his companion, who stood with his hands in his pockets and his hair very much crumpled, looking at him askance. The light of admiration was in Rowland’s eyes, and it speedily kindled a wonderful illumination on Hudson’s handsome brow.[12]

If the admiration here were only that delayed from Rowland’s appreciation of the statuary alone, we have to wonder of the effect of the detail in the description of Roderick and its effect on Rowland of seeing something ‘handsome’. A fire passes between the men after all metaphorically that has to have reference. I do not think this is just about a shared interest in plastic and figurative art. Likewise, much later, Rowland feels, in the narrator’s words but Rowland’s projected point of view, ‘exquisite satisfaction in his companion’s deep, inexpressive assent to his interest in him’.[13]

Other signals are socio-cultural. In my recent blog on a new biography (with a queer focus) (use link to access the blog) of James’ great friend, John Singer Sargent, I cited the queer contexts which made the Venetian gondolier of interest to men who had sex with men as an example of the kind of working-class man stereotyped as available to the rich and refined, including:

… the ambivalence of Addington Symonds over the glorification of exotic European versions of the non-industrial service-working working-class, such as those that Fisher calls the ‘accommodating gondoliers’ of Venice, whose availability to rich queer or ‘questioning’ patrons was legendary. These ‘accommodating’ men were often also accommodating because of poverty and may be more strongly associated to male brothels that adorned ‘Belle Époque Venice’.[14]

Now read this passage concerning a ‘couple of days’ in Venice as pent by Rowland and Roderick, apparently dealing with an artist’s coming to terms with Titian and Veronese’s colouring on one morning wherein:

the two young men had themselves rowed out to Torcello, and Roderick lay back for a couple of hours watching a brown-breasted gondolier making superb muscular movements, in high relief, against the sky of the Adriatic, and at the end jerked himself up with a violence that nearly swamped the gondola, and declared the only thing worth living for was to make a colossal bronze and set it aloft in the light of a public square.[15]

Sargent’s Portrait of Henry James and some Venetian fancies of the Gondolier

The colossal erection imagined by Roderick may be the outcome of aesthetic musing but it derives from rather minute perception of muscle men, already typecast among artists of all kinds. Alongside this are the ‘bromantic’ moments of the novel in which the artist Sam Singleton (singleton being the perfect naming for a confirmed bachelor) shows his dedication to a bigger man: ‘The little water-colourist stood with folded hands, blushing, smiling, and looking up at him as if Roderick were himself a statue on a pedestal’.[16]

There are even more pointed looks at the kind of men thought of aesthetes in the 1890s:

certain gentlemen who walked about in clouds of perfume, rose at midday, and supped at midnight. Roderick had found himself in the mood for thinking of them as very amusing fellows. He was surprised at his own taste, but he let it takes its course.[17]

These men are ‘attached to ladies’ like women who like luxury, but their moral dubiety seems queerly encoded. And perhaps the most coded of bromantic moments is when Roderick parts from Rowland, ostensibly to think of the fact that Rowland has loved Mary Garland since he ‘first knew her’ and has remained silent. Roderick may wish Rowland ‘had mentioned it’ but it is too late. It is a scene pregnant with the unsaid but in no way does it help us to understand the complexity of the emotions that will at this very parting drive Roderick to his death, accidental or otherwise. There are uncomfortable hints in words like Rowland’s to Roderick that he tells her of Mary in order ‘to rebut your charge I am abnormal being’.[18] There is pointed excess of incomprehension of each of each and of both by us as readers in the moment of parting:

Suddenly Mallett became conscious of a singular and most illogical impulse – a desire to stop him, to have another word with him – not to lose sight of him. He called him and Roderick turned. “I should like to go with you,” said Rowland.

“I am fit only to be alone. I am damned!”

“You had better not think of it all,” Rowland cried, “than think in that way.”

“There is only one way. I have been hideous!”

This moment is like the monster in Frankenstein realising his own monstrosity, but for me it reads too of a man, I mean Roderick, realising that his ‘maker’s’ love for him might not be all consuming, that he might, unknown to Roderick, love a woman too. Roderick traded on the abnormality of Rowland that is being denied, that Rowland loved Roderick and Roderick alone. Of course, this is NOT what is being said intentionally. The point is that the scene insists that neither of the two men at this moment know WHY they are acting as they are, and the ball falls in the court of a readerly interpretation. And for Rowland, Mary is forgotten as soon as Roderick dies. The end of the novel is a larger ending for Rowland than can be stated: ‘Now all that was over, Rowland understood how exclusively, for two years, Roderick had filled his life. His occupation was gone’.[19] That last line self-consciously parodies Othello’s ‘Farewell! Othello’s occupation’s gone!’ (III, iii, 409), wherein the military man gives up his military career supposedly as a consequence of the infidelity of his wife, and, perhaps, with all his soldiers. But why this portentous echo? I think it is because not only has Rowland nothing to fill his time, Roderick being dead, but that his whole purpose is lost, as indeed is Mary Garland’s, who ‘had flung herself, with the magnificent movement of one whose rights were supreme, and with a loud, tremendous cry, upon the senseless vestige of her love’.[20] In such a competition, Rowland has no claim to make on Roderick (‘senseless’ as he always was) for Mary’s ‘rights were supreme’ but isn’t this always the case in the realm of the heteronormative to the man who has never, and can never, speak a ‘love that dare not speak its name’.

Take this of course, for what it is worth, which may be extraordinarily little, especially for the homophobic or the believer in a kind of fictive purism of the text, where meanings are never queered, by any agency whatever.

All the best & love,

Steve

[1] Henry James (1875) Roderick Hudson (page references to Kindle Annotated Classic Edition (using page not location detail given therein):317 of 352

[2] This was indeed the phrase remembered exactly so perhaps smutty teenage lasts longer than I think since I am now 68. It is in Chapter XIII of the novel.

[3] James op.cit.: 19 of 352

[4] Ibid: 21 of 352

[5] Ibid: 22 of 352

[6] Ibid: 70, 243, 111, 116, 183, 284, & 306, respectively.

[7] ibid:317 of 352

[8] Ibid: 349 of 352

[9] Ibid: 174 of 352

[10] James op.cit.: 19 of 352

[11] Ibid: 23 of 352

[12] Ibid: 31 & 32 of 352

[13] Ibid: 150 of 352

[14] See: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/03/paul-fisher-makes-an-unanswerable-case-for-abandoning-the-labelling-of-complicated-multidimensional-traits-in-the-life-of-this-artist-in-favour-of-liberating-the-opulent-complexities-which-t/

[15] James op.cit: 66f. of 352

[16] Ibid: 78 of 352

[17] Ibid: 97 of 352

[18] Ibid: 341 of 352

[19] Ibid: 350 of 352

[20] Ibid: 351 of 352

One thought on “In Henry James’ ‘Roderick Hudson’, a plain but wealthy young urban American man, Rowland Mallett, uses his great fortune to nourish in Rome the talent of a potentially great sculptor, Roderick Hudson. Many conversations between them sound odd out of context, such as this one: ‘“It was your originality then – to do you justice you have a great deal of a certain sort – …… You were awfully queer about it.” / “So be it!” said Rowland. “The question is, Are you not glad I was queer?”’ A set of reflections based on Henry James (1875) ‘Roderick Hudson’.”