Visiting London: A Preview of the Highlights on my visit with Justin from Monday 17th – Wednesday 19th April 2023!

First section including National Theatre visit is updated here: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/04/21/an-update-blog-on-seeing-dancing-at-lughnasa-by-brian-friel-on-monday-17th-19th-april-2023-7-30-p-m/

The National Theatre, Southbank hosting Dancing at Lughnasa, The Lightroom at Kings Cross hosting Hockney, Victoria & Albert museum hosting Donatello.

I always prepare for cultural or art events. Thinking this was unusual, as a result of passing comments or the self-reflection of others in idle chatter (at least mine was idle), I said I was doing this to my bestie Justin, since we will be going together to the events I will be previewing, from my own perspective, here. He said he did the same, so perhaps I aren’t that unusual. But maybe, anyway, we should not think of preparation for experience of art in any form not as artifice rather than nature, for I think it is not. Strangely enough, these thoughts were reinforced from my current reading – I have been reading on and off, but on Kindle, Henry James’ Roderick Hudson since I wrote my blog on the artist Sargent (see this link for that blog).[1] James writes, clearly from the point of view of Rowland Mallett, about the virtues of Mary Garland, a young woman on her first visit to Rome from rural New England, in relation to her visits to locations wherein great art can be accessed,. It offered a beautiful counterpart to my thoughts about both Justin and I, though I doubt either of us would claim ‘intellectual purity’ as its motivating force:

She wished to know just where she was going – what she would gain or lose. This was partly on account of a native intellectual purity, a temper of mind that had not lived with its door ajar, as one might say, upon the high-road of thought, for passing ideas to drop in and out at their pleasure; …. … now Rowland had spoken to her ardently of culture; … she was pursuing culture into retreats where the need for some intellectual effort gave a noble severity to her purpose. She wished to be very sure, to take only the best, knowing it to be the best’.[2]

There is always a danger in quoting Henry James with regard to self or others that you import with the quotations claims for the supposed qualities of that same self or others of too earnestly Arnoldian a kind, such as ‘intellectual purity’ and ‘noble severity’, true daughters of Mathew Arnold’s master terms; ‘sweetness and light’. Who wouldn’t want to be seen in those grandiose terms, even if their grandiosity is precisely what is inaccurate in them. The truth is far from that which these words-on-stilts convey and, in a sense, the earnest words of Henry James form a kind of parody for motives which, if not those of mental ideals, are based in actuality on beliefs that only formal education can inculcate: that one owes it to oneself to benefit from what might have cost an artist a whole life in achieving, a great work of art.

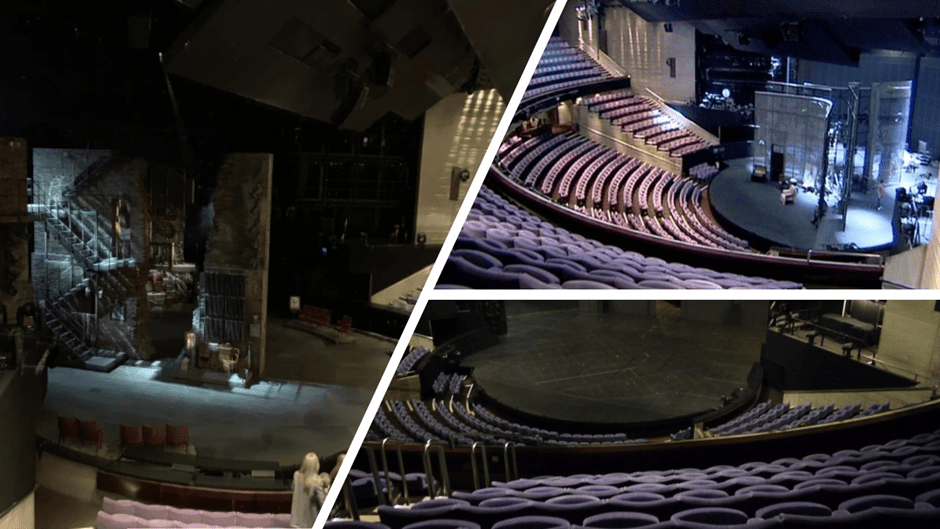

The idea of ‘pursuing into retreats’ is of course full of irony for though enlightenment by culture is often a private thing – based on working at it, at least in part; its origins and its outcomes are only valuable when shared and developed. And part of the joy for both Justin and I will be in visiting these events in venues which are social and are placed in a wider social context, of the experience of the differences of culture open to one in a capital city like London. Part of the joy will be London itself and traversing its streets and underground travel conduits. Even the architecture (exterior and interior) of the venues will please. There is a joy in accompanying Justin, for instance to the amphitheatre of the Olivier Theatre, for I know this is a place he goes to for the first time. Its dependence on the idea of a revived classical theatre speaks from its scalloped sides, a thing one can appreciate without the nationalism that went into its conceptual planning for its shape is truly one from a Pan-European and paleo-global origin in the past – the amphitheatres of the Greek Classical city-states, including those in what is now coastal Turkey, Magna Graecia, the Alexandrian conquests in the Middle and near East, and the Roman Empire thereafter in even its ultimate spread to the North.

It’s the dullest alternative of proceeding but I will take each event in te order of seeing it; giving titles for them in bold as I go.. We can start with:

Brian Friel’s Dancing At Lughnasa at the Olivier Auditorium in the National Theatre, South Bank. Wed. 17th April. 7.30 p.m.

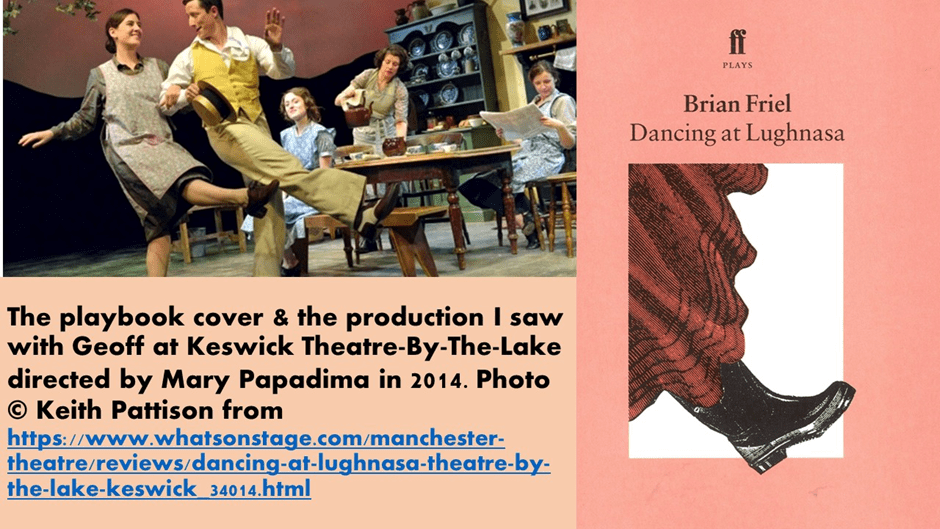

This is a play I have some slight history with, having seen the play at Keswick Theatre-By-The-Lake in 2014 with Geoff, my husband and then read it. It has a prose style that, like other favourites of mine in Irish playwriting, sings like poetry – those favourites by the way are Sebastian Barry and Patrick McGuinness. Dancing At Lughnasa is a play obsessed with the comparison between the smallness of the apparent lives of a community of women and the wide interior landscapes of human desire. Friel sets it in Ballybeg, a fictional town in Donegal (though there are many Ballybegs across other Irish Republican counties) for, as Wikipedia tells us:

Ballybeg is an anglicisation of the Irish language term, Baile Beag, which means “Little Town”. Ballybeg is the name of a number of small townlands and villages in Ireland.[3]

In fact, as Friel’s dedication to ‘five brave Glenties women’ (his aunties) tells us, Ballybeg is inspired by the real town of Glenties with its loughs and cottages, field and town transferable to other Irish settings:

Shortly after the play at Keswick I watched the star-laden film with its filmscript as revised and devised by Patrick McGuinness but dominated by its stars, particularly Meryl Streep, who nevertheless played an appropriate stiffly repressed Kate in a way that her emergence from under cover is something to see. I loved the film too. Wonderful that the role of Rose (of whom the playscript notes say, ‘Rose is simple’) is played by Kathy Burke.[4] She is an actor who redeems the uncomfortable feel of Friel’s adopted simplification of her, even in the film shot below wherein Burke looks at but also through, towards the film’s audience in effect, the figures of Kate and the illegitimate son of their sister, Chris, as if looking between them at us as well.

It’s true that the ‘looking at’ or ‘being looked at’ that occurs in the film (and the play when well directed) is well supported by the text. Moreover, I expect the National Theatre will pull out all the intelligent stops on this. In the screenshot I refer to above all the sisters, not only Rose, are looking, if some do so surreptitiously with the air of wishing to be the unobserved observer, out at the foreground, for observing is itself of importance in the play’s spaces – it is part of the environment at the cottage, small holding, gated fields, moorland lochs and town streets invoked otherwise in the play for eyes are everywhere. There is constant surveillance operative between the sisters. In part this is a matter of care, especially in relation to the vulnerabilities of Rose. When Rose goes missing, she must be found before others see her – lest she be in the arms of a man, even a ‘wild’ man’.

When after anxious search plans have been announced for the family members, ones that exclude the police, in whom there is NO safety from public exposure, Chris shouts: ‘Look – look! There she is!’ for she has seen her ‘through the window’. Even now Maggie stops Chris from being an observed observer, holding the latter back from view so that ROSE remains ‘unaware of their anxious scrutiny’.[5] Staging the play means that the audience not only sees the actions performed but also sees other persons on the stage seeing the action, intuiting thereby those same person’s interpretations of it or its actor as well as their own. Thus, to know this play is to know what surveillance is in a community habituated to surveying itself and others observing them, a community where we must understand even Kate’s strictures against ‘savage’ or ‘pagan practices’ because they might be suspected of anyone. Listening is implicated too because pagan ‘talk’ also must not be heard ‘in a Christian home, a Catholic home!’. The word ‘Catholic’ here matters much more than the word Christian for it invokes a society of surveillance and control from above. That this surveillance is based on a contradiction is clear: because, whilst denying its possibility in a Catholic community, it must always look for that behaviour it pretends to be impossible. It is as if it knows pagan practice to exist underneath everyday appearances, just as the pagan practices of Lughnasa (‘in the old days August the First was Lá Lughnasa, the feast of the pagan god, Lugh’ [pronounced ‘Loo’]) underlie Catholic ceremonies and thoughts about what is unfamiliar or strange in the everyday. An example of the everyday becoming estranged is found, for instance, in Maggie’s obsession with the family’s first ‘wireless set’.[6]

Managing the unobserved observer in various productions of the play.

The master of unobserved observation of others is the narrator, the older Michael, whom in the first half of the play observes the women from his memory, vicariously imagining Friel’s own observations of his aunts in Glenties. This is so much emphasised to be the case that the young Michael of older Michael’s memory has to be invisible, in this first Act at least. Friel says it in a stage direction thus:

(The convention must be established that the (imaginary) BOY MICHAEL is working at the kite materials lying on the ground. No dialogue with the BOY MICHAEL must ever be addressed directly to adult MICHAEL, the narrator. …).[7]

The sisters observe men, especially dancing or men celebrating Lughnasa, as if they were not only evident monsters of nature but also beings requiring the enchantment of being desired. Chris and Gerry, the unmarried parents of Michael – who indeed will never marry – dance observed:

CHRIS: They’re watching us.

GERRY: Who is?

CHRIS: Maggie and Aggie. From the kitchen window.

GERRY: Hope so. And Kate.

Meanwhile, on the same page in the script, and heard by us but not Chris and Gerry, the following dialogue puts dancing into its varying equivalence with sexual contact that comes and goes throughout the play – whether the talk is of Ballybeg in Ireland or talk of the Uganda of Jack’s priestly past:

MAGGIE: They’re dancing.

KATE: What!

MAGGIE: They’re dancing together.

KATE: GOD forgive you!

MAGGIE: He has her in his arms.

KATE: He has not! The animal![8]

Yet Gerry is a man not tied to one woman (he is always associated with Cole Porter’s ‘anything goes’) and he can sing songs to his son’s mother’s sister, Agnes, with lines like ‘If bare limbs you like’, dance with her and kiss her whilst he is observed through the same kitchen window through which the sisters saw him and Chris earlier, by Chris. The stage direction reads:

All this is seen- but not heard – by Chris at the kitchen window. Immediately after this kiss GERRY burst into song again, turns AGNES four of five times very rapidly and dances her back to the kitchen.

That these women, apart from Kate, respect the power of human sexual attraction is not condemned, but empathised with, in the play, even though such attractions may cause hurt and damage. There is no condemnation, except again through Kate’s eyes, of Agnes’s thought that she would dance with any of many men not caring ‘how young they are, how drunk and dirty and sweaty they are’.[9] Yet the play is not so simplistic as to damn the faults either of the moral surveillance within Irish Catholic communities either, even the lack of integrity of some of its priests, whose spirituality turns out to be less than that of Jack, even at his most pagan subjection to the gods of Uganda and the kites that represent them on his return to Donegal, and in his love of his ‘house-boy’, Okawa. Jack’s alienation is not unlike that of Gerry, which sends the latter to volunteer for the International Brigade.

It is 1936 in the play, after all, wherein the build up to war against the Fascist Right in Spain was already recruiting followers like Gerry (and against organised Catholicism of a different sort – hence Kate’s disapproval yet again of Gerry). And the alternative to a caring society that constantly watches you is that Irish women like these get lost (literally unseen) down the maw of a rapacious imperialist capitalism in England: the play provides a description of the anomie and alienation of capitalism as fresh as that any Marxist. It starts with the lost sisters working as ‘cleaning women in public toilets’, in factories, and in the Underground until spat out into unemployment and destitution where Agnes ‘died of exposure’ (but now the exposure to hard privation not the moralising eyes of Ballybeg. Rose goes to a ‘grim hospice’ and dies ‘in her sleep’.[10] Now, I think that seeing this with Justin – and knowing his openness to the pain of those marginalised by our society, for we all touch on these lives sometimes, will be wonderful for he is, more than I, so much more aware of the ambivalences of the notion of a caring Catholic Christianity, that holds up Love regardless of ideology, however it mires itself sometimes in the latter too. For this is a play where a merely rational intelligence in watching it would be no intelligence at all. It has to be felt. How the production handles all this I’m keen to report upon.

Now some of the emotional content of this play must come in the ability to manage joyous communal sharing – particularly in shared actions that either are, or approach, dance (even if like Rose you dance in Wellingtons). How dance is handled and observed matters as the narrator Michael constantly makes clear. And the pre-publicity photograph for this production below shows that message is centrally in the director’s scope.

Kate’s dancing is BOTH ‘controlled and frantic’.[11] Dancing demands to be seen as not merely ambivalent but multivalent, an appearance of harmony that might signal disruption too. It creates unease or, in the true sense of the word, dis-ease:

And even though I was only a child of seven at the time I know I had a sense of unease, some awareness of a widening breach between what seemed to be and what was, of things changing too quickly before my eyes, of becoming what they ought not to be.

This is pure poetry, as is the resolution of dance into religion and poetry, something Jack learns in Uganda to be that which shows ‘no distinction between religious and secular’.[12] It makes for impossible stage directions suggesting dance by Friel such as: ‘The movement is so minimal that we cannot be certain if it is happening or if we imagine it’.[13] In Michael’s narration at the end of the play, this becomes poetry or religion; certainly ritual. In his memories:

Everybody seems to be floating on those sweet sounds, moving rhythmically, languorously, in complete isolation; responding more to the mood of the music than to its beat. When I remember it, I think of it as dancing. Dancing with eyes half-closed because to open them would break the spell. Dancing as if language had surrendered to movement – as if this ritual, this wordless ceremony, was now the way to speak, to whisper private and sacred things, to be in touch with otherness.[14]

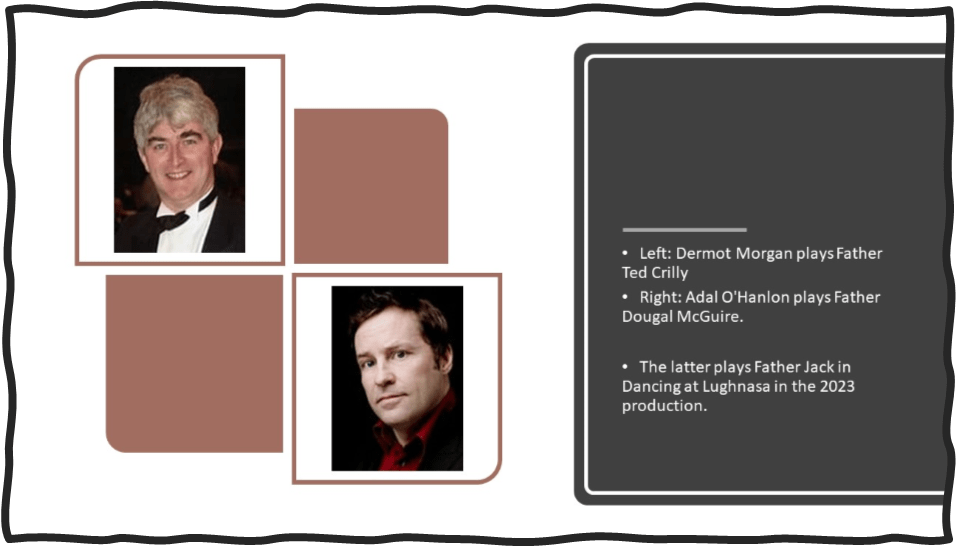

When Justin and I see this I will be interested in how the ‘simple Rose’ will be played and with what sensitivities to people with a learning difficulty or disability, the handling of the wordlessness in Jack’s dementia state (Jack is played by Ardal O’Hanlon, so I wonder how the actor will put away his past from Father Ted) and how the company translate Friel’s impossible directions to dance as if they are either not quite doing something recognizable as such or something meaningful beyond a dance per se – for there is no doubt that handling dance innovatively is crucial to how the play will make meanings that adhere in minds that observe and reflect on the play. Look at this direction for instance, where four sisters:

… are all now doing a dance that is almost recognizable. They meet – they retreat. They form a circle and wheel round and round. But the movements seem caricatured; … and the almost recognizable dance is made grotesque because – for example – instead of holding hands, they have their arms tightly around one another’s neck, one another’s waist.[15]

Is this a director’s path to creative freedom or a closed nightmare where meaning isn’t going to emerge for anyone? For an audience, it may be exhausting and Justin and me must be up the next day. Up for:

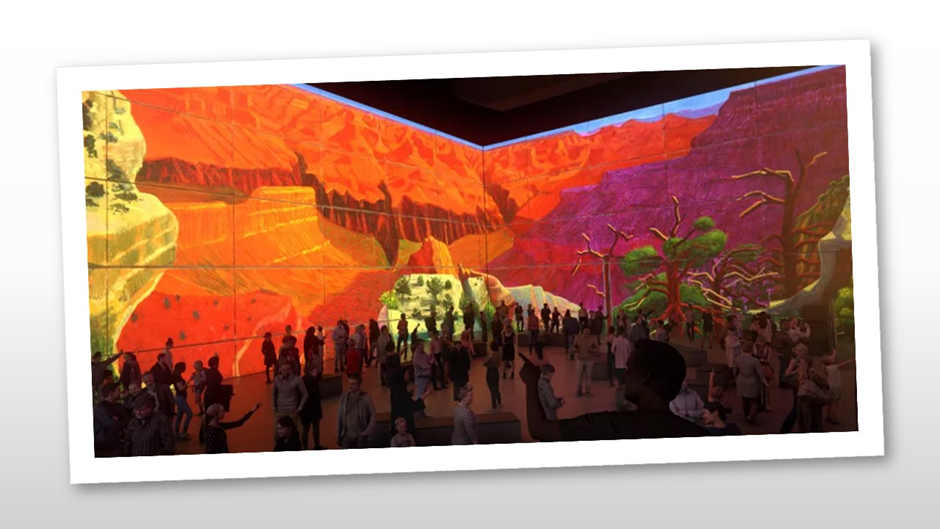

‘David Hockney: Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’ a light show involving the artist’s own collaborative input at Lightroom in Kings Cross (the launch show for this venue). Thurs. 18th April. 11.30 a.m.

Having seen Ardal O’Hanlon in a play the night before, it is more than spooky that this new production of the filmed and variously projected paintings of David Hockney, so multiply projected that what we see is sometimes fragmented or sometimes joined without seams, is called ‘Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’. These words are those Father Ted Crilly uses to teach Father Dougal about the mysteries of perspective. The rather daft Father Dougal was a part that made O’Hanlon’s name as an actor as famed as it is.

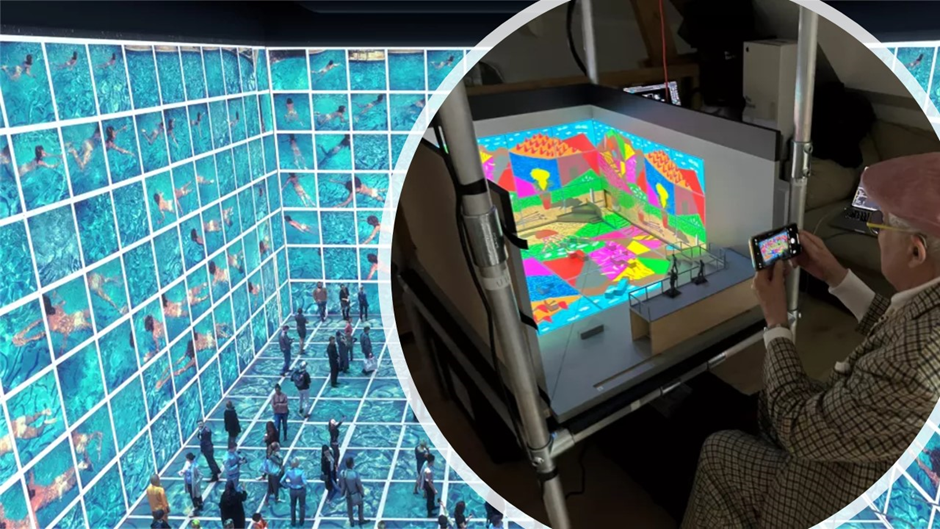

The words’ Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’ themselves are internally rampant with confusion and this is totally appropriate to an artist who has made the way the academic study of perspective in painting a large part of his life-work. He has examined how the influence of the state-related painting academies of the European eighteenth and nineteenth century has, by its insistence on a narrow unitary perspective in painting, ruptured ‘pictures’ from their audience and destroyed mass joy in those ‘pictures’. [The most relevant of my blogs on this issue can be accessed at this link]. This is one reason that Hockney’s ‘Eye’ has become focused on showing how fragmented are the data that assemble pictures through the optic nervous system and how important to other traditions than that in the West are multiple and shifting perspectives associated to another dirty word in the academies – that of ‘narrative’. Although different to narrative in words, stories are essential to Asian artistic traditions. In telling stories themselves, light shows are described as an ‘immersive experience’. We are immersed not just in arrays of pictures and colour, sound, and sense, but the viewer’s body becomes destabilised and detached from conventional views of reality by its baptismal immersion.

Of course Hockney is only one of the makers important in this work: ‘it is a joint venture between design studio 59 Productions and the London Theatre Company’. It is the first show in a new artistic venture, the Light Room in Kings Cross; hence, the 4-storey building itself, with a hollowed out show space, will be great to see and report back upon. However, there will be more that I cannot predict in this show. Interviewed by T. F. Chan, for the online journal Wallpaper*, last year Hockney acknowledged that light shows that must, at least, be a little like that we will see of Hockney have been made about both Monet and Van Gogh. [Indeed Justin, Geoff and I saw the one on Van Gogh (see my blog linked here)]. Chan says:

Asked about inevitable comparisons to the slate of immersive exhibitions (notably reinterpreting the work of Van Gogh and Monet) that have cropped up in recent years, Hockney is unfazed.

‘They are just using Van Gogh and Monet, and they’re dead. They can’t add anything to it,’ he quips. ‘Well, I’m still alive, so I can make things work better.’

And Hockney’s involvement in planning the event involved work with stage models of the show, imagining how it may be seen from any point in the room is shown in the collages below, adapted from Chan:

In a rondo alongside the model of what the fragmentation of the painting Gregory Swimming might look like above, we see him working on the part of the show involving California’s San Gabriel Mountains; pictures of such starling colour contrast and narrative tonal twists that demand, Hockney thinks, a Wagner soundtrack. Hockney actually narrates through some sequences of the show. This will be wonderful to see and hear. In its 50 minutes duration, it is said to have ‘six chapters’; which terminology is itself a claim about how the genre of the book enters into what is otherwise just thought of as multisensory experience with few boundaries. If Dancing at Lughnasa plays with seeing and being seen and further, being seen seeing, Hockney thinks this might be true too of this show:

If we begin to see the Grand Canyon anew in the sequence pictured above through artistic making then all the more so in that way anew will we see his more recent work done from Bridlington and its area and in Normandy, his current home.

‘We’ll have those nine big camera works of spring, summer, autumn and winter on the walls, but you’ll be looking up, [it’s] amazing to be really looking up at them. The audience will feel on it, they will feel in the forest, they will feel on the cliff. It’s changing everything.’

Perhaps lunch after this will be a silent reflective experience, but is that the style of Justin and Steve, enthusiastic shared and sharing (and sometimes loud) reflectors. But then it may be in South Kensington we eat, for in the afternoon, there follows:

‘Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, Thurs. 18th April. 3.45 p.m.

How to preview this exhibition remains a problem because though I have received and read the catalogue on this show and it has already been widely, and enthusiastically reviewed, with 5-stars in both The Guardian and i newspapers, this preview was difficult to plan. My reading hasn’t built my expectations of the event in any clear way. I read most of the catalogue, if only skimming the more ‘art historical’ chapters on patronage and nineteenth-century copyists and forgers, and found the book intellectually exciting and full of things I was pleased to learn. The reviewers tended to tell me more about them than the show. The most interesting issues in the book for me were: first, the relevance of the goldsmith’s craft (for as we are told there is no word Donatello could use for ‘art’ that didn’t also mean ‘craft’) to the making of art that intended to carry meanings; second, to the commitment to conveying the truth of human emotion in art over beauty.

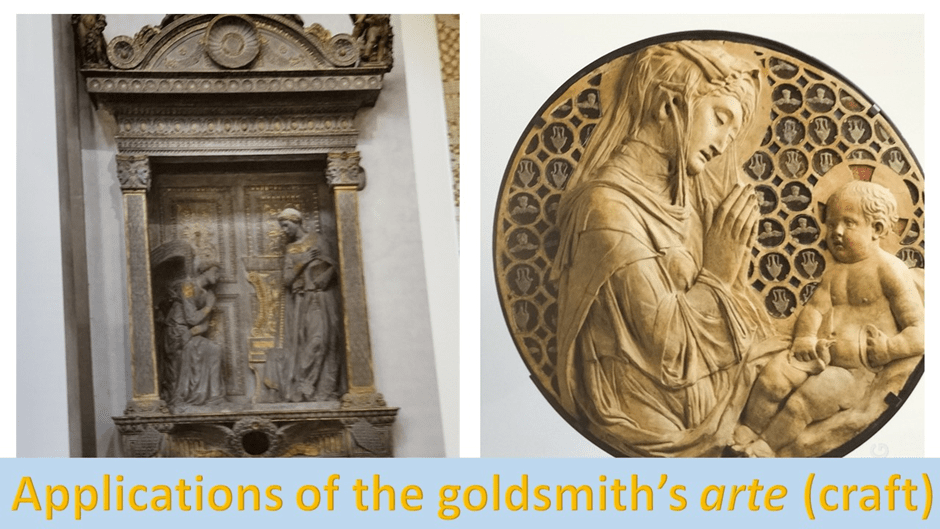

First then let’s take gold-crafting and its relevance to the themes of art and the distinction of nature and art (and even artifice). It did this, we will see, sometimes in ways that challenged conventional theories of the artist’s role or indeed the Church as a patron. For it seems the goldsmith was as oft faking the idea of ‘gold’ as he was actually crafting in it, often not just by the obvious means of gilding, where, surfaces pass as solid realities, but also by intriguing combinations of media that feed into the work’s production of iconographic meaning as well as its appearance. In one sense Florence Hallett, reviewing for the i, says rightly that the exhibition, and certainly the catalogue does this for it is all I know as yet, ‘does an excellent job of elucidating the way that a Renaissance sculptor worked, and how his early training as a goldsmith may have helped him to work with such exceptional finesse and fluency’.[16] I would add to her praise ‘such exceptionally reflective and reflexive ways of creating meaning’ I think. Hallett is a restrained critic.

One example, though unfortunately not exhibited, is analysed in the catalogue. Here the goldsmith’s craft is used in a piece from Santa Croce in Florence, the Cavalcanti Annunciation. In this Donatello uses local sandstone (magnicio), not usually a choice for religious art because of its association with the common and earthy, but offsets it with the use of gilded ornaments of jewellery stone. It is thus ‘transfiguring the’ (common) ‘stone’. The patron family become thus associated by the use of a rich red jasper to both enhance and spiritually lift the meanings associated with their family motif. These basics of gold smithery transform the social and spiritual meanings of the piece, Alison Wright argues, so that the piece became known as the ‘Stone Annunciate’: a piece to ‘contain and effectively embody the Virgin’s pliancy to salvation history as she becomes the mother of God’. [17]

Illustrations from the catalogue (Petta Motture (ed 2023.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From pages 39 & 163, respectively.

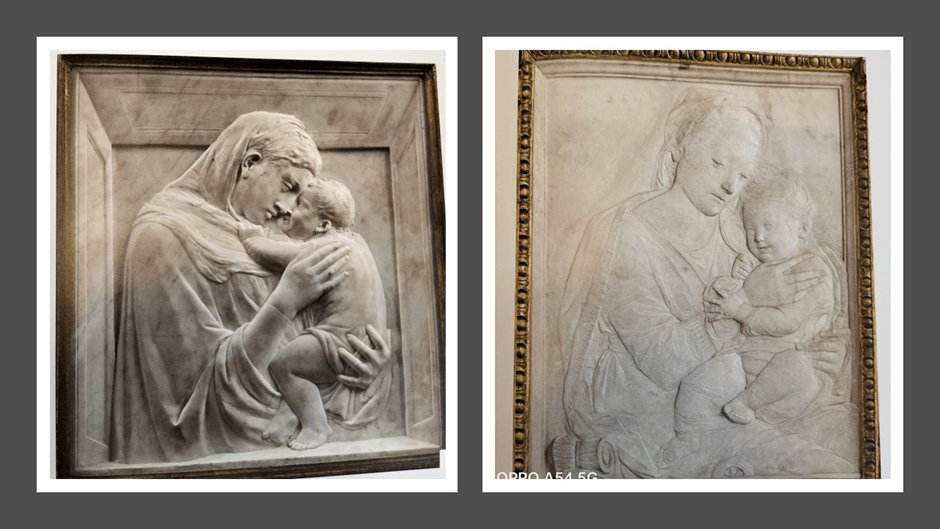

In my collage above I show the beautiful ‘Stone Annunciate’ as it appears, muffled by my photography, in an essay in the catalogue. Nothing as stunning as this represents the goldsmith’s arte (craft in English) from the exhibition I think but, nevertheless, the tondo of the Piot Madonna (named after its French nineteenth-century purchaser, Eugène Piot) is stunning. In it the virgin is captured having glimpsed, as if suddenly, the divinity of her fleshly son. Not only the fleshed out relief is realistic in effect but also the mother’s expression as if caught in surprise, if piously so. There is almost a dynamic tremble on the lips whilst divinity itself radiates from the effect of the jewellery-style gilding and roundels containing icons in white wax lifted onto the surface of read wax (how did this survive?) of alternating double rows of classical vases (possibly a symbol of incarnation as containment) and seraphim.[18] The piece has such volume in appearance that it seems to come alive in the space in front of the tondo. The effect is like that of jewellery that intends to overblow the story of its significance, a goldsmith’s function lent to religion.

I cannot guess though yet how Justin and I will react to what we see. Some metaphors by critics show more the mood of the critic than raise expectations in oneself, such as Jonathan Jones in The Guardian talking about the exhibition as, in the end, like ‘catching quicksilver’.[19] He seems to think that this is something to do with the means in which the art elevates just at the moment that it makes us fully conscious of the earthy and fleshly, like the buttocks of the God, Attis-Amorino, one of his favoured pieces. Yet THIS little god of ‘ecstasy, his willy hanging out, waving his hands in the air as he raves’ may be passed over, he also says, because of embarrassment, or to convey a sense to others that one prefers higher things, but remains part of the total experience of the show, Jones insists. Likewise, the earlier figure of a thoroughly Biblical and spiritually educative David by Donatello, done well before the better known erotic and classicised version of a lithe hermaphroditic boy show a bifurcated artist. Behind Attis Amorino in the show, we can see below is a gilded seraph. What better way of pretending one isn’t looking at the ‘naughty boy’ with his trousers slipping down and gilded poppy pods promising rich psychedelic visions on his belt?

The catalogue puts the Attis-Amorino figure in the context of the spiritelli, practically a speciality of Donatello so that The Daily Mail’s Robin Simon says they were ‘infectiously joyous spiritelli made for a baptismal font: boyish sprites full of fun and invention, dancing upon scallop shells, that inspired the bronze figurines of the Renaissance’.[20] Such a glib characterisation somewhat underplays the importance they have in the catalogue of showing how playful was Donatello’s ability to mix medieval cherubs, doing the service of God on earth and used for religious purpose with the sprites used in ancient pagan art. For these artworks proclaim it says ‘the porosity between what were sometimes viewed as opposing belief systems’.[21] No doubt they were also used to create a titter amongst secular humanists. However, this play between the decorative and functional (even if the function is a sacred one) may also have derived from a set of attitudes inculcated by crafting goldsmiths. [22]

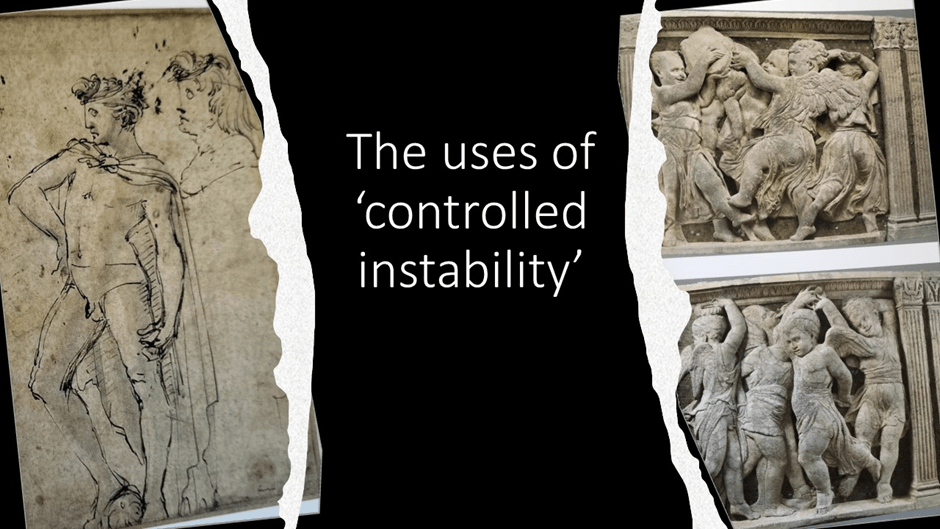

The Attis-Amorino is remarkable, but it is also reflected in the more formal spiritelli also shown in the exhibition. Moreover it might be mirrored to in their use as marble relief in pieces such as Dancing Spiritelli (see below right for a detail). From their place on a church pulpit, their joy seems somewhat wild, and their attitude, pose and gesture balletic and exaggerated. Intended perhaps for Marian celebrations, they look as stoned as Attis-Amorino may be. The catalogues calls their poses ‘adventurous’ and the effect is of dynamic movement.[23] Marc Bormand in a catalogue essay indeed traces the heritage of the spiritelli to pagan religions, including representations, in Roman funerary ornamentation found near Pisa, of ‘the cult of Dionysus’. He goes to say that ‘Donatello took the opportunity to create a variety of poses based on controlled instability’.[24]

Illustrations from the catalogue (Petta Motture (ed 2023.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From pages 125 & 135 respectively

The idea that a chaotic flux might underlie the harmonies of a controlled dance (and idea is relevant to Brian Friel’s play too) would have charmed both secular and religious Neoplatonists of the period, but they might also have appealed to those who invested more into the body than the soul as the source of value. The toppling sense of a fall about to come amongst these maenadic spiritelli may also recall the exuberant instability of Attis-Amorino and of the human ‘sprites’ which adorned Florentine life amongst her youth – such as the show-off youth, with his penis poking out from his underwear in a drawing attributed to Donatello in the exhibit of David Triumphant (left in collage above). This David recalls the homoerotic pose, where the fall is not just to the earth but to lust, of the most famous David sculpture of Donatello’s, represented in this exhibition a nineteenth-century copy.

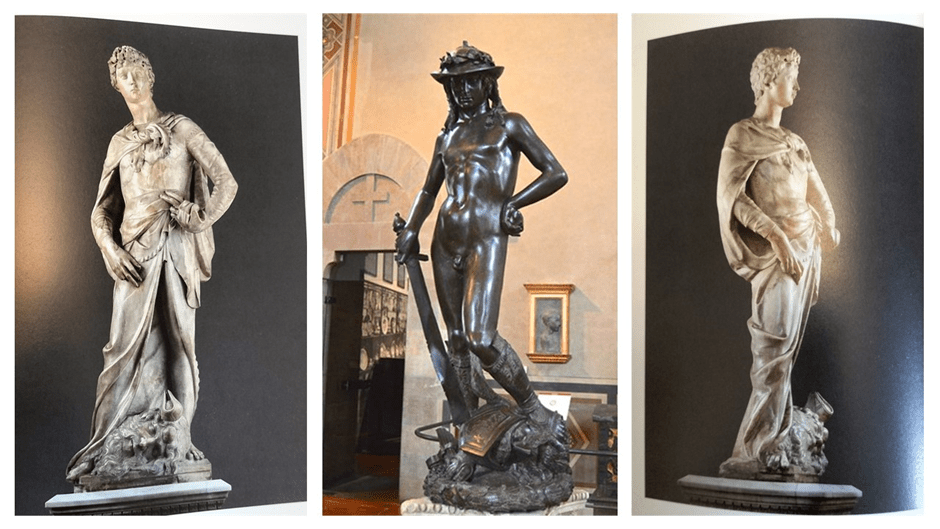

Before we move on though we might compare that famous David with an early and more unknown one of Donatello’s, which does appear in the original here.

The late David in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (centre) and 2 aspects of the early David (c. 1408-9) from Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From pages 107 & 106, respectively.

The same pose appears in the later boy David as in the drawing (don’t we always want to call him Camp David); controlled but not stable. The early David is classical but more Roman than Greek in style and has both a Biblical and military feel. In fact although commissioned for Florence Cathedral, it was later bought by the Florentine government as a martial image of inevitable victory in war. Jonathan Jones still finds it attracts attention to the body (‘his garments attract your eyes to the way it curves in space’) and, for what it is worth I find this evokes a more adult eroticism than the later David, which feels uncomfortable to many (me included).[25] Hallett admires, rightly, its virtuosity for a young man barely 20.[26] It is a sensual piece of course. It is made so by the use of a leg-hugging aperture created by the drapery. It needs to be seen though to decide its effect – on me at least.

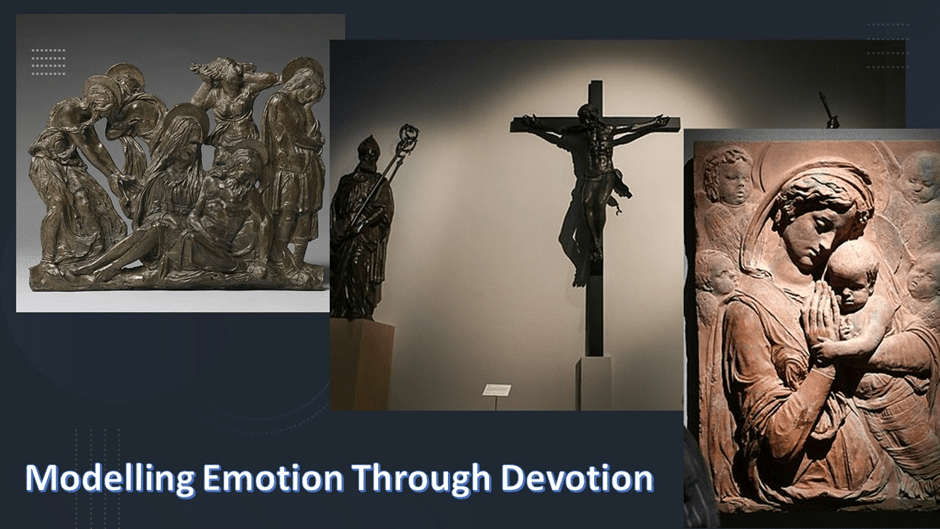

However, we need to look at the other theme of the show too, so brilliantly discussed in the catalogue, that looks at theme from the early polychrome statues in the medieval tradition to the later relief sculptures especially of the Virgin. Timothy Verdon in a catalogue essay argues that the so-called greater interest in ‘character’ over ‘beauty’ discerned by Jacob Burckhardt is better interpreted as based on the belief in medieval theology, and in some Neoplatonist thinkers (even secular ones), that people need to be stimulated from the seat of their emotions ( “in parte sensitiva” according to Aquinas) in order to follow a path to God based on knowing the truth of one’s own sin.[27] Hence we need to look finally at how the exhibition shows the modelling of devotion through the pathway of the emotions.

In the instances in the collage above there is a wonderful stress on the expressions and interactions of feeling that are discussed beautifully in the catalogue, especially the expression of sorrow or love in the face (and sometimes as with this beautiful relief Virgin, both at the same time). So I will not dwell here until I have seen the originals for myself. However, one point is worth stressing, since it was only clear to me from an illustration of a piece that will not be represented in this exhibition, and which appears below reproduced from the catalogue.

A detail of the ‘Assumption of the Virgin’ from the frieze on the Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci from Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From page 17

What strook me here from the offset was that the perspectival depth of the field is end-stopped by the appearance of diaphanous clouds, through which angelic faces and other body parts emerge or into which they fade are conveyed by an amazing use of the depth of the carved relief and the effects of perspective this encourages at the eye. The shell in which the Virgin sits seems moulded from air and cloud. The wave-like rhythms in the stone destabilise any certainty we have about what we see, and even angelic bodies fade apparently into or through each other. Meanwhile the virgin, though at a perilous angle, seems solid, in the way the angels are only very partially and in parts of their ‘bodies’. I yearn to see this piece but will not. What I will see is nearly as good but only nearly.

The Pazzi Madonna (1420-5) left by Donatello compared to Desiderio da Settignado’s Pachiata Madonna from Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing. From page 159 & 155 respectively

The Pazzi Madonna (left in the collage) is surely a most beautiful inbuilding of emotional depth into a piece of semi-theatrical artifice. The inset frame appears to mime physical depth whilst being little more that a way of insisting on the artifice which has made the divine flesh. It is stuffed full of visual uncertainty, for the torso cannot be imagined in the same space as the child, who actually stands on the stage of the internal frame structure. It recalls that art still had roots in the ‘para-liturgical theatre’ (as named by Timothy Verdon) of the late medieval church.[28] This torso comes from a different genre to the child – not a view that would have passed muster in the Counter Reformation. However Mary’s clothing appears to emphasise the resistance of the ground on which it appears to stand. It is as if realist factoring were used to emphasis the lack of realism of this element. The catalogue calls the space the figures stand in ‘abstract’ but this is surely not the case. It seems to refer to the faction of art instead. Though the other Madonna here superficially recalls Donatello’s method – the use of low relief for instance. However, the lack of physical depth recalls the greater depth, both physically and emotionally of the Pazzi. Of course seen by me in the flesh this may not seem the case. I may again have to rely on Justin’s eye for detail here where mine fails, especially in the interpretation of liturgical meaning and Catholic ritual emotion.

At this point the events of this short break end and the next day will see us both return to Durham. When it comes to summing up this preview, I think a common factor in all three experiences is that they deal with art that relies on overwhelming arrays of detail in many dimensions. We don’t see it all and may understand less. I will add to this blog, with a new one or an appendix, to give the gist of the effect of seeing these things ‘for real’ after we have been. But maybe I can be reassured by this statement of Petta Motture about the art of Donatello with its ‘variety of both overt and hidden messages’. In some cases she goes on to say, of Attis-Amorino, ‘the layers of meaning remain largely lost to us’. Thus is life, but the love of art and talk about it is a great restorative, and regained meanings don’t have to be of the scholarly type! It might be like, as Justin says below: ‘Nothing screams paaarty like a bit of controlled instability’.

All the best

Steve

[1] Henry James (1875) Roderick Hudson (Kindle Annotated Classic Edition).

[2] Henry James (1875) Roderick Hudson (Kindle Annotated Classic Edition Loc.3599-3605 edited omissions).

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballybeg

[4] Characters and Set, Loc. 41 (Kindle ed.)

[5] Ibid: 56

[6] Ibid: 1

[7] Ibid: 7

[8] Ibid: 65

[9] Ibid: 12

[10] Ibid: 60

[11] Ibid: 22

[12] Ibid: 48

[13] Ibid: 71

[14] Ibid: 71

[15] Ibid: 21

[16] Florence Hallett (2023:23) ‘The goliath who gave us David’ in the I (Sat. 11 Feb. 2023). P. 23.

[17] Alison Wright (2023: 40) ‘Making and Viewing: Encountering Donatello’s Sculpture’ in Petta Motture (ed.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing, pp. 34 – 47.

[18] Petta Motture (ed. 2023: 163) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing, For the containment idea see Alison Wright op.cit: 41.

[19] Jonathan Jones (2023: 15) ‘Carnal delights that lift your soul to the heavens’ in The Guardian (Thus. 9 Feb. 2023). P. 15.

[20] Robin Simon (2023) ‘Italy’s Original Renaissance Man’ in The Daily Mail (online) [01:36, 17 February 2023]. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-11760233/Italys-original-Renaissance-man-Donatellos-masterpieces-comes-London-V-A.html

[21] Petta Motture op.cit: 190.

[22] Ibid: 179.

[23] Ibid: 134

[24] Marc Bormand (2023: 67) ‘Donatello: Past to Present’ in Petta Motture (ed.) Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance London, V & A Publishing, pp. 61 – 73.

[25] Jonathan Jones op. cit: 15.

[26] Florence Hallett op.cit: 23.

[27] Timothy Verdon (2023: 49f.) ‘Devotion and Emotion: In the Art of Donatello’ in Petta Motture op.cit: 49 – 59.

[28] ibid: 52

3 thoughts on “Visiting London: A Preview of the Highlights on my visit with Justin from Monday 17th – Wednesday 19th April 2023: on Brian Friel’s ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’, The new David Hockney light show and Donatello at The Victoria and Albert!”