Jonah Raskin in a waspish review in The New York Journal of Books says that Nino Strachey’s new book on the extended life of the Bloomsbury generation has ‘opted to focus on gender and sex …. In an era of LGBTQIA+ that might be an opportunistic choice in terms of publication and readership’.[1] This blog shows why we still need to deplore the sad need of academic values to seek to prolong its hegemony over the priorities for human development and growth and the even more sorrowful (to me) sectarianism of a sexual politics that is ‘LGB without the TQI+’. It praises the simple honesty of Nino Strachey (2022) Young Bloomsbury: The Generation that re-imagined love, freedom and self-expression London, John Murray.

Although Jonah Raskin in his review’ in The New York Journal of Books believes that ‘discussion of Woolf’s novels and essays would have made for a far more substantial and valuable work ‘, it’s grossly diminishing to see Nino Strachey’s new book on the extensions of the Bloomsbury generation as merely something readers ‘can’t not be entertained’ by and as a concoction of: ‘pithy quotations and racy gossip’. I would argue, or perhaps just insist, that these comments are ‘diminishing’ since ‘substance’ and ‘value’ is surely not the preserve of academic discourse alone or about what mainstream literati acknowledged already as ‘substantial writers’ write in public essays or statements. Raskin indeed says, in a tone we used to call ‘anal’, if not downright mean:

‘Strachey depicts Virginia Woolf as a gossip hound who wrote, for example, “I fell in love with Noel Coward, and he’s coming to tea.” Bully for her and bully for him. She does not go in for literary criticism, which now no longer occupies the exalted place it once did in publishing and academia’.

I find the ubi sunt style of this lament for the passing of elitist literary culture somewhat depressing since I doubt if ‘literary criticism’ (a selective view after all about what is significant and of value even when it was handled by Scrutiny and F.R. Leavis) ever did, in itself, much good in the world to which it felt itself superior. Both its ties to notions of cultural elitism and its sad dismissal of ‘modish’ thinking, now usually dismissed as ‘woke’, are probably the reasons for its decline. Such attitudes barely need to be articulated by mourners of the hegemony of elitist academic discourse; instead they underlie the ironic, perhaps even sarcastic, tone of the phrases I quote from Raskin in my title that say that this book ‘opted to focus on gender and sex’, rather than on her public stance on pacifism. It’s kind to call his explanation for this only waspish: ‘In an era of LGBTQIA+ that might be an opportunistic choice in terms of publication and readership’.[2]

In fact it has the odour of a kind of sorrow for the loss of bourgeois job-opportunities that holding chairs in literature in the universities might have given a person like Raskin but that odour is surely misleading, since Raskin is a professor of media communication, having given up a post in teaching literature at universities in order to take up radical politics in the 1980s. Nevertheless, some of the people who did that, as pacifists rightly fighting the Vietnamese adventure of American governments, might still be snooty (and some definitely are) about what they (Tony Blair is one such) call ‘identity politics’.

That Virginia Woolf was a ‘gossip hound’ (undeniable I think) is still of interest whatever our estimation of her considered and published thought about social issues, such as pacifism over war (for her the First World War), or the values of her great art, for it is such I agree. In my opinion, we will never understand why novels like Mrs Dalloway, To The Lighthouse or Between The Acts are great novels if we do not realise and relish the role of bourgeois interfamily social gossip within them. Moreover people like Raskin invoke the idea of ‘an era of LGBTQIA+’ in order to diminish that terminological attempt to grasp diversities in human reality as something merely passing, usually with the overheard susurration in their voice that means, ‘and the earlier it passes the better’.

Will any reviewer, I thought to myself, pick up on why Nino Strachey herself says why the subject matter of the book ‘matters’ to her? Of course she is a Strachey and past members of the same Strachey family form a large part of this book, presided over, of course, by Lytton Strachey. But Nino says it matters to her most because of young Strachey family members who are not yet established in the world: ‘As the mother of a child who identifies as gender-fluid and queer, I have learnt some sad truths about the ongoing impact of prejudice’.

In her Introduction she goes on to cite the effect of prejudice on trans children especially, for in Stonewalls’s 2017 report 84% had self-harmed and 45% attempted suicide. She dedicates the book to that child, Cas, and ‘all those who push beyond the binary’. [3] Let me say right now, that however privileged a person and family Nino and other Stracheys are, in the view of all the North American reviewers I cite (and she and her family are, of course, very privileged), I applaud this defence of her child’s choices and of the realities in that child’s life which the linguistic content of her dedication represents. In the light of the death by violence of Brianna Ghey (unfortunately not an isolated incident), and the horrific defences of transphobic discourse by people on Twitter who call themselves gender-critical gay liberationists and radical feminists even in that event’s wake, I have been made to pause at contemplating any likeness to people I once thought of as great names in queer history, let alone in traditional literary criticism.

Rest in peace Brianna Ghey

In fact one queer reviewer does refer directly to Strachey’s dedication to her child and other gender-fluid persons, though from a position of rather superior antagonism that I frankly find hurtful as a long-term campaigner for queer rights and solidarity between sexualities. It remains the truth that trans issues are misunderstood and marginalised by heteronormative and equally pernicious homonormative thinking. For instance, the otherwise wonderful gay male writer, Andrew Holleran, gives a substantial review, by the quantitative standards of the journal, of this book in the latest edition of The Gay & Lesbian Review. However, he ends the review by lamenting the ubiquity in it of ‘queer’ as an adjective for describing sexual and romantic phenomena. The word ‘gay’ he says comes up once in a very marginal role, whilst ‘queer’ is, as he describes it, the books ‘operative word’.

Of course, like Raskin, Holleran is clearly entertained by the book, giving personalised interpretations of his joy at the characters; telling us just why they entertain him. ‘It would be hard to imagine a more formidable queen than Lytton Strachey’, he says. He demonstrates glee too at the identification the male group of ‘Bloomsberries’ as a whole as represented by ‘the pale star of the bugger’ by Virginia Woolf (she ain’t half got a tongue in her that lady!). I imagine his public titter at seeing Woolf identifying Cecil Beaton likewise as a ‘Mere-Catamite’ or enjoying the title (for he clearly has not read it – see my blog on it at this link) – Bloomsbury Stud on Tommy Tomlin.[4] Had Holleran read this book, he might have noticed how unsatisfactory either of the terms homosexual or bisexual was to describe Tommy’s complex and shifting sexualities.

Holleran sort of vindicates Nino Strachey’s interest in the theme of there being two Bloomsburys – an ‘Old Bloomsbury’ and an extended set of rather more depoliticised “Bright Young Things”. However he picks out a second theme only in order to lambast it, for Holleran has no time for faddishness either, in that he is like Raskin, about “gender fluidity”. Throughout he queries this term, finding ‘it hard to say just what Bloomsbury was: bisexual, homosexual, polyamorous, gender fluid, or simply English intellectual’. It is strange though that Holleran finds his difficulty in labelling the behaviour here (despite the recourse to a rather bizarre stereotype of Englishness) not a reason, as I do, for preferring the term ‘queer’ to conventional category labels with less fuzzy boundaries of definition. By the end of the review he says that most of their ‘behaviour can be understood within the homosexual and bisexual categories’ and again goes on to attack Strachey’s use of ‘gender-fluid’, as if he was fighting for his LGB Alliance membership card to be upheld.[5] I have yet to understand why anyone would want to reduce human behaviour to explanation by oversimple binaries of either sexuality or gender. Perhaps the most disappointing of Holleran’s jibes is the choice of ‘sexual changeling’ (mockingly using a word popular in Elizabethan English) to nominate a trans character like Woolf’s Orlando in her eponymous novel featuring takes on both Eddy and Vita Sackville-West.[6]

This said, I think it’s quite clear, whatever the deficiencies of Nino Strachey’s book in terms of its organisation of an argument and its dependence on family stories, though often a story from otherwise unpublished letters that ought to appeal to scholars, it is not merely a kind of ‘musing’ prose. Nor is it fairly called a ‘desultory, rambling sort of book, without a timeline, overview, or single figure to carry us through’. Such put-downs, which might damn many a post-modernist writer, occur too in Raskin’s review but not quite with the agenda here of attacking ‘gender ideology’ (in scare quotes because, of course, I do not see gender as an ideology) in particular. There is some appropriate insight into Strachey’s motivation when Raskin says, thus admitting that there is a kind of value to thinking again about Bloomsbury even if only one of ‘style’:

To this day, Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic occupy public offices, pulpits and plutocratic realms and want to repress individuals unwilling to fit into little boxes. Hence, the timeless appeal of the bohemians, the Bloomsbury folk, and more recently the Beats. Books about them will never go out of style.

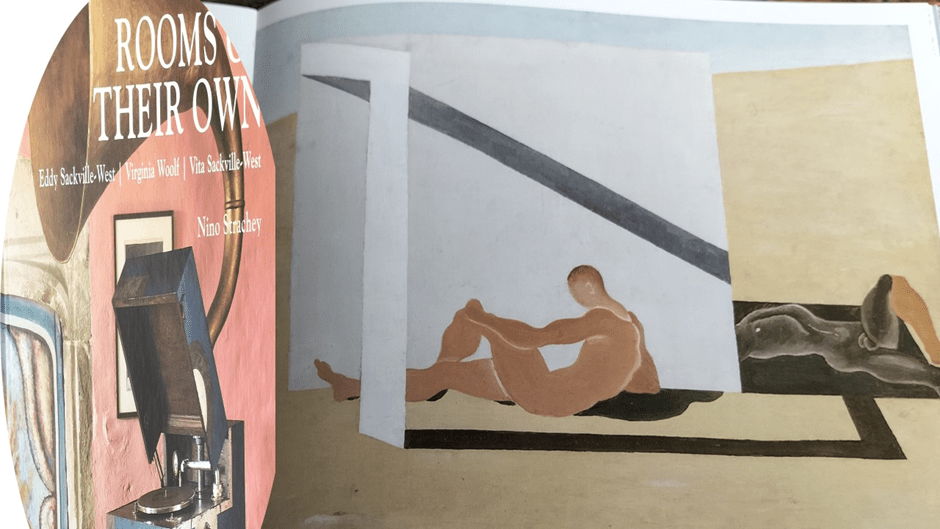

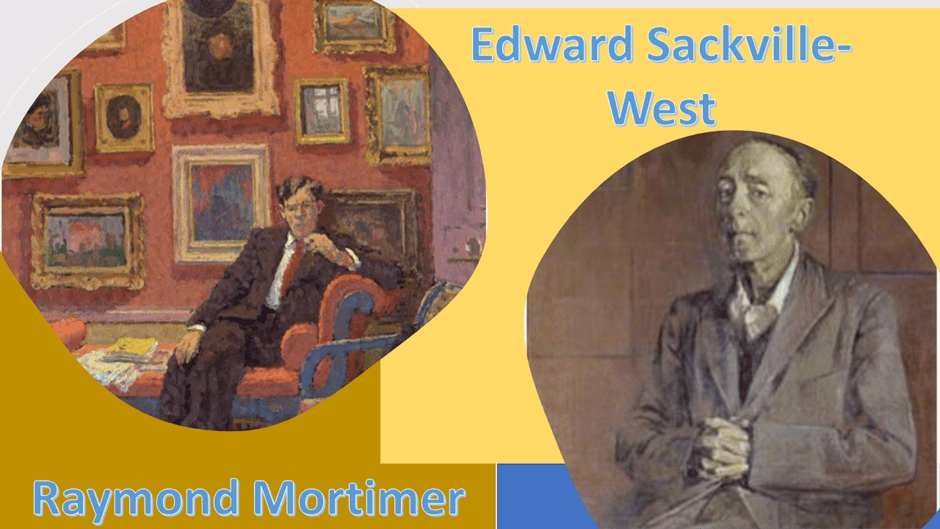

Moreover Raskin has done his homework and knows the literature, even Nino Strachey’s earlier book for the National Trust, which I love: Rooms of Their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West. This book is acknowledged by Raskin as ‘skin in the game’ of Strachey’s to burrow ‘into the Bloomsbury byways and highways’. [7] I have valued this book, published by the National Trust ever since its publication for it extends our understanding of the concept of ‘interiors’ so essential to what we call ‘decoration’ in the Bloomsbury era and among its wider circle,. The circle includes people Strachey elaborates upon in her new book, Raymond Mortimer, and Dorothy Todd, both queer marginal ‘Bloomsberries’ who wrote a book on interior decoration for Vogue: they were its editors. Interiors are about lives and they are in ever shifting interaction with the exterior appearances that manifest how change and diversity across a group both in the moment and across durations of time are being experienced and articulated to others. That is the secret of queer sexualities and one that Strachey does not need to bruit, as it is so easy to bruit apparent but constructed constancies such as binary sex/gender and sexual options (within ONE or TWO sexes).

Details of cover of Nino Strachey’s earlier book for the National Trust, Rooms of Their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West and page 135, John Banting’s exploration of queer values beyond many binaries: light / shade, white / black, trans-chrome & monochrome, and exterior and interior.

Strachey’s books are written in a popular easy-to-read manner, but they look at history in terms of apparent mere contingencies in history that also represent wider themes: notably truths about the complexities of shifting interactions within the whole biopsychosocial system that come to light only apparently momentarily through the long duration of history. In that system facts, feelings and values make each other up (much as Bloomsbury socialites – to extend the pun – made themselves up before brief parties on the stage of life) and become more solid fleshly ways of living this life of for human animals.

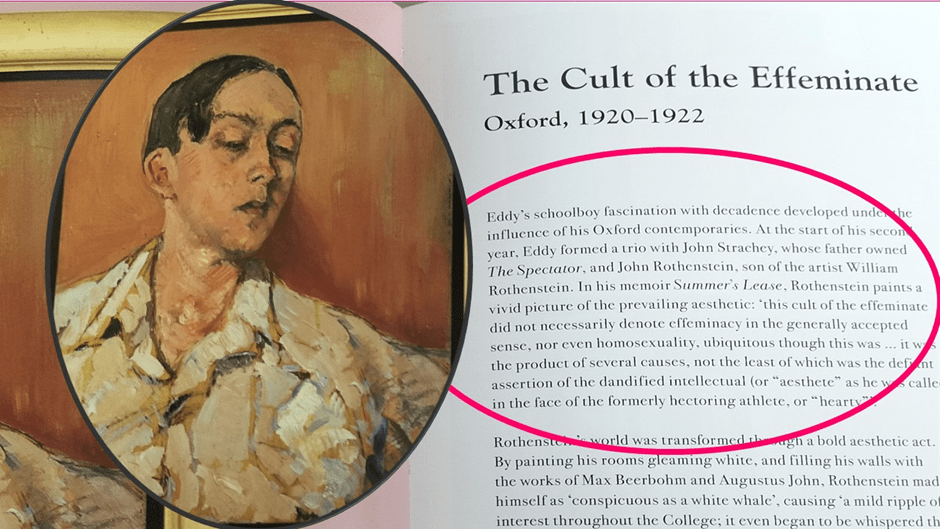

Details of the book opening which is pages 14-15 of Nino Strachey’s earlier book for the National Trust, Rooms of Their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West in a re-arranged collage of text and portrait of Eddy at Oxford in 1920 by Ian Campbell-Gray.

Her chapter on the ‘cult of the effeminate’ sees the confluence of many different currents (from small and personal to the large domain of the socio-political) as they become the flow of history. First there is what is particular to Eddy Sackville-West, in no way a representative person, second the movements in socio-cultural history and taste, and finally the shifting socio-political tectonic plates that linked Eddy’s anarchic behaviour to the possibilities that allowed John Strachey to become a Marxist-tending Labour MP. What is richly described in the former book of Nino Strachey’s is only merely suggestive of conclusions about the life of Bloomsbury that are left to the reader to enhance in their careful reading. Those suggestions are elaborated more in this second book (yes, mainly through storytelling) in a way that respects the reader’s freedom to build from the basic facts, ideas, feelings and values described. I love this and hence do not miss the lack of a hegemonic reading demanded by the male reviewers I have cited above.

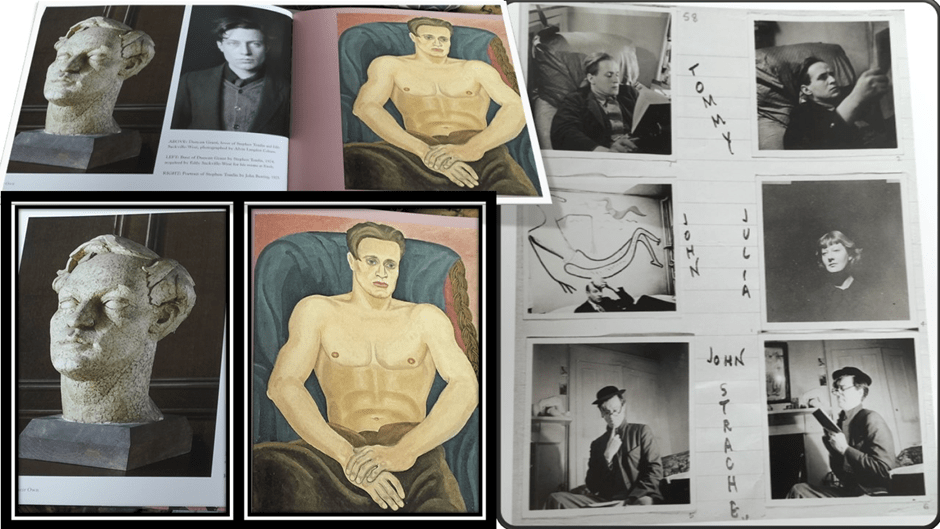

The variegation of public psycho-sexual appearances explored even in visual evidence in Rooms of Their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West. Details from page 28 – 29 on the refashioning of masculinity and the object of masculine desire in the lives and art of Tommy Tomlin and Duncan Grant, and from page 45 showing main actors from the second book: Tommy Tomlin, Julia, and John Strachey.

In that spirit, I will allow the pictures in this piece and my captions to suggest the arguments that link both books. They are not explicit ‘arguments’ in fact in the old terms of established monolithic discourse (determinately male) but hint at a history that can be resistant to singular new directions desired by some and subject to unforeseen historical accidents. All anyone is left with is that diverse opportunities that must be snatched from historical accidents. (If they cannot be snatched, for some, sadly, such as Carrington following the death of Lytton, the only opportunity left it seemed to her was her own suicide).

But historical accidents have to be faced by most and are. For instance, how could John Strachey have realised that his political mentor in the Labour party would, after election of both of them, leave Labour and set up a new supposedly socialist party and then (horror of horrors) turn it into the basis for the British Union of Fascists, for that mentor was Oswald Mosley. John Strachey did not lose his socialism like Mosley (though definitively the ‘champagne socialist’) but became a lone voice in the political wilderness rather than the force for major social change he had envisioned. Nevertheless, in 1932 he was still predicting The Coming Struggle for Power: An Examination of Capitalism, in the book of that name[8].

In this book stories of John and Julia Strachey (pictured above from the earlier book) do get told more fully and do get interlinked with the stories of not only Tommy Tomlin but countless other young ‘Bloomsberries’, as these informal social groups transform into other groupings. One such group was the Crichel Boys, including an older, more sober, Eddy Sackville-West and Raymond Mortimer (see this link for my blog on that group); the story of which fills Nino’s final few pages of her book on Young Bloomsbury. In her picture of this convivial weekend home of elegant weekend parties, art was an aspiration to generosity and vice-versa. It nurtured queer sociability as non-exclusive, even if only for the privileged meeting outside the eye of draconian laws that criminalised them. The social dreams of a nation were the poorer. We need to revisit them.

Of course the heyday of young Bloomsbury, where Stephen Tennant made havoc within the heart of Siegfried Sassoon, had infinite traits that were, to say the least, a celebration of superficiality. For instance Nino Strachey says that Tennant’s ‘clothing designs explored the boundaries between masculinity and femininity’.[9] No doubt the cognitive and emotional content explored went sometimes no deeper than the first layer of clothing and how it looked, but to query ‘custom’ is, as so often in the novels of Virginia Woolf, to query much more than the surface appearances that it seeks to change. For instance Alix Strachey, after a serious affair with Nancy Morris ended (the latter was the daughter of the queer painter and friend of Francis Bacon, Cedric Morris) confided in Eddy Sackville-West. She did it in a way that suggests to me that experiment in the external appurtenances of identity was in part a search for an otherwise unknowable interior of the self, one not prescribed by genetics, custom or politically passive versions of ethical behaviour:

You know I sometimes feel that all this ‘self-respect’ & decency is a kind of dead surface one has grown to cover under & not be seen; & I’d like, just once, to pull it off & show what’s really there in myself and others.[10]

I love that phase: ‘grown to cover under’, which in breaking grammatical form innovates with meaning, where what is under is what is over, what is interior is also an exterior, and what is growing is already dead. Hence the tendency to contrast the seriousness of Old with the superficiality of Young Bloomsbury may be yet another binary ready to be overturned and, to some extent, if subtly, Nino does this in her book: showing how the mix of the Old and Young meant neither was seen as anything but a series of varying continua in different domains with a different pace sometimes dependent on the domain. Lytton Strachey’s or Maynard Keynes’ affairs with young men were far from end-stopped encounters: they built careers. Young members like W.J.H Sprott, the sociologist. Amongst the women, Alix Strachey, a serious psychoanalyst shifted the ways in which the psychosocial was thought about in later careers. Virginia Woolf, though she played with the idea of an anti-Bugger revolution felt that if young and old were bathed in conversation wherein the ‘word “bugger” was never far from our lips’ advantages occurred. Because people across boundaries mentioned ‘openly’ what was, in Alix’s terms, ‘grown to cover under’, ‘leads to the fact that no one minds if they are practiced privately’, and thus ‘custom and beliefs are revisited’.[11]

I really do hope you read and enjoy this book. Nothing in it forces conclusions and will not do so for you as it did not for me, I think. But the stories in this book add up to experience of lives beyond one’s own, opening up potential rather than closing it down and giving hope for something better than just being entertained. For queerness is expansively innovative. One can like Holleran and Raskin just be entertained by Nino Strachey’s stories, but you are also forced to confront how other people’s experience of having the boundaries of the normal swept aside, like Julia Strachey listening to the stories of the problem of having overmuch anal sex with her uncle Lytton, must have changed things for themselves and others so that persons were no longer shut up in themselves. As a result supposed glass ceilings could be shattered by those boldened to query ‘custom and beliefs’ in the world of relationships, social organisation, and work where, in each case, polyamory was possible, equal relationships encouraged, and depression and joy acknowledged as equally the fruit of life, making endings no surprise. I loved it. Give it a go.

All the best & love,

Steve

[1] Jonah Raskin (2022) ‘“Pithy quotations and racy gossip exhilarate Young Bloomsbury.”: Review’ in New York Journal of Books. Available online at: https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/young-bloomsbury-generation-redefined#:~:text=Reviewed%20by%3A%20Jonah%20Raskin%20“Pithy%20quotations%20and%20racy,to%20the%20Greenwich%20Village%20bohemians%20of%20the%201920.

[2] ibid.

[3] Nino Strachey (2022: 13 & 267 respectively) Young Bloomsbury: The Generation that re-imagined love, freedom and self-expression London, John Murray

[4] Andrew Holleran (2023) ‘Dora & Lytton & Ralph & Frances’ in The Gay & Lesbian Review [XXX, (1), Jan-Feb 2023] 25 – 27. The title Holleran chooses for his article is he reveals (p. 25) a play on the film name Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice.

[5] ibid: 27

[6] ibid: 26

[7] Raskin, op.cit.

[8] Nino Strachey (2022) op.cit: 249

[9] ibid: 134:

[10] Alix Strachey cited ibid: 210.

[11] This, from Woolf’s diaries, cited by Holleran, op.cit: 25