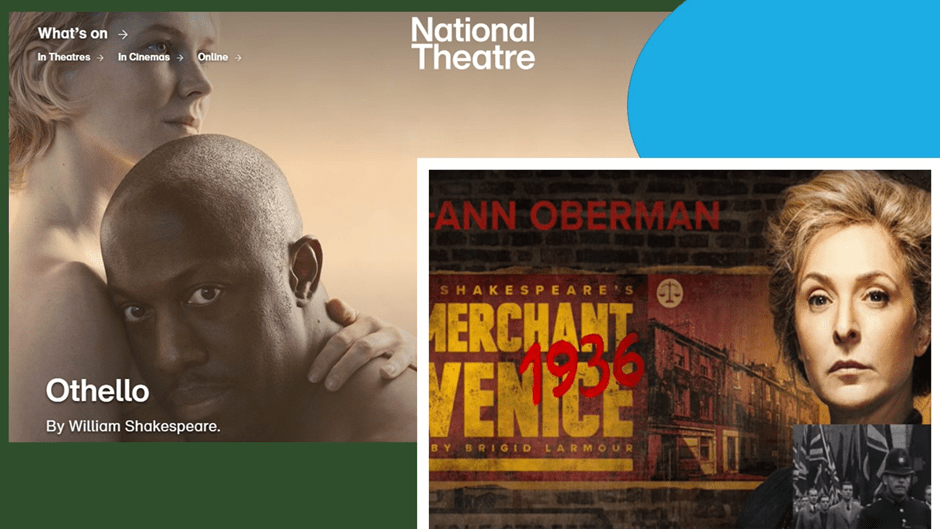

The ‘Elephants in the Room’: racism in the British artistic ‘heritage’. This blog written to prepare me to see new productions of Othello (National Theatre Live streaming 23 February 2023 at Gala Theatre Durham) and The Merchant of Venice (Watford Palace Theatre tour at Home theatre, Manchester 16th March 2023).

In a previous blog: I wrote:

I am going to see Othello in a week or two, the streamed National Theatre Production, and would like to blog about these two plays simultaneously for they are ‘Elephants in the Room’ of British artistic culture, both deeply racist plays (it is undeniable that this is the case as I will argue) but both also famed as plays which challenge the racism they also depict.

So hence this piece.

That both plays are ‘racist’ needs context of course because they are often produced as if both exposing and critiquing racism. Nevertheless, according to Arifa Akbar reviewing the live theatre production (The Lyttleton Theatre of The National) for The Guardian, it appears to open by clearing the debris of racist tropes dogging this play, She summarises the expectations this opening scene gave her, with some style, thus:

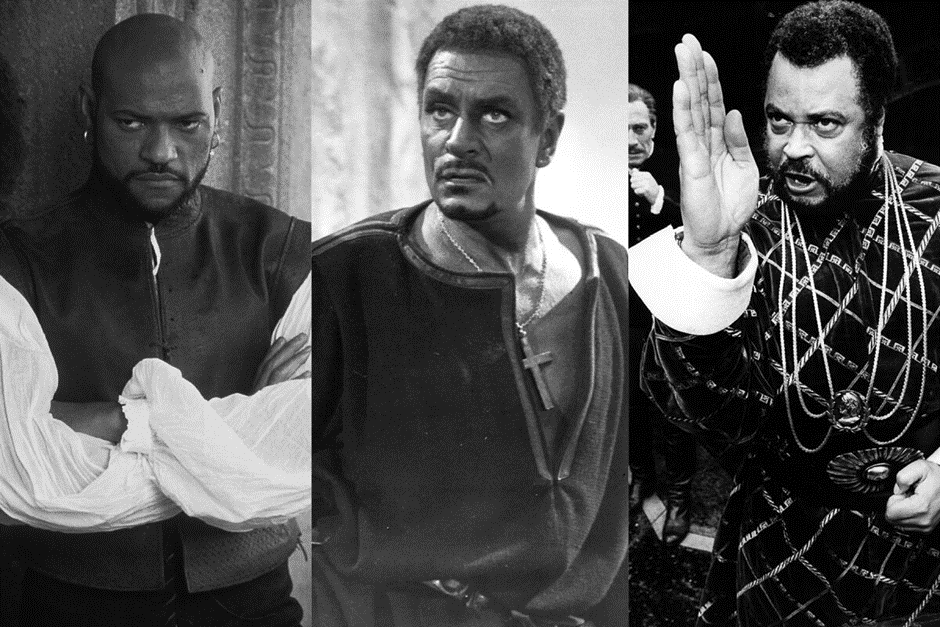

In 1964, the National Theatre Company staged Othello with Laurence Olivier playing the military commander in blackface. Clint Dyer’s new production speaks to the play’s murky performance history in its opening optics, perhaps even to the ghost of Olivier’s Othello himself. There are posters of old productions projected on to Chloe Lamford’s spare, contemporary set and a cleaner scrubs the floor. It sets up a conceptual overhaul – a coming clean, of sorts.[1]

Murky performance history … Peter Eastland (Ensemble) in Othello at the National Theatre. Photograph: Myah Jeffers (picture and caption from https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/dec/01/othello-review-clint-dyer-national-theatre )

The long shadow of Laurence Olivier is part of my own history with regard to the reception of this play. It’s a fairly long history because it is a play I have always loved and used to choose to teach when I taught literature. However, the first performance of the play I ever saw was the filmed version of Olivier’s performance. The actor played the role in blackface, deepening his voice in a way that made him seem not far from the stereotypic semi-comic figures that played in the same period of entertainment history every Saturday night on BBC in The Black and White Minstrel Show. My English teacher at the time pointed out how much verisimilitude was possible to great actors using the Stravinsky method. For his pupils however, it was an introduction to merely another stereotype, I think, although the teacher’s innocence of such an aim has to be asserted too.

My impression of being somewhat offended by the gross nature of the acted style at the time came back to me when I read, for this blog, Charles McNulty, academic and theatre critic of The Los Angeles Times. McNulty addresses these very issues here in a brilliant commentary on the resurgence of a debate about the racist intention of white actors playing Othello in blackface. His commentary was sparked by ‘composer Bright Sheng, being compelled to step down from his class at the University of Michigan for showing the Olivier film’ to his class of students of Verdi’s Otello. McNulty himself showed the film to students but not because he valued it, as Sheng did, but because he felt the history of the play’s reception needed that exposure.

McNulty’s view of the film is like mine, I think. He says, of what he summarises as a ‘repugnant performance’, that he was: ‘Horrified by Olivier’s racialized prosthetics and West Indian minstrelsy, …’. And though I claimed the innocence of my white English teacher above in showing the film, one needs to remember what passed for critical innocence at that time, not least in theatrical and film critics. McNulty cites the influential film critic, Pauline Kael, ‘that she saw fit to anthologize in For Keeps: 30 Years at the Movies, published in 1994’:

“Olivier’s Negro Othello — deep voice with a trace of foreign music in it; happy, thick, self-satisfied laugh; rolling buttocks; grand and barbaric and, yes, a little lewd — almost makes this great, impossible play work.”

He continues to point out that there was little that was truly innocent about ‘blackface’ in the light of a white privilege that most white people did not recognize. Moreover, perhaps it is the case that the play itself is offensively racist since the great actor, Sidney Poitier, said when he refused to play the part that ‘he could not “go on stage and give audiences a Black man who is a dupe.” Nevertheless this was not the view of other great actors of colour, Paul Robeson and James Earl Jones, for instance. Nevertheless in creating a role that created a character that was a ‘problem’, ethically as well as representationally, we will have to agree that we cannot blame Olivier’s choice of style in playing Othello on Olivier alone, for McNulty is correct in saying that: ‘Like it or not, Shakespeare is implicated in this history’. And we cannot either simply say that the play is about something else than race. McNulty’s view is again like mine, saying that far from abstracting Othello from his skin colour: ‘Shakespeare takes pains to emphasize Othello’s racial and cultural difference just as he stresses Shylock’s religious separation in The Merchant of Venice, a work even more heavily freighted with controversy’.In these words McNulty mirrors my motives in writing this blog. Moreover, perhaps he also concludes in ways too that I want to test out in the productions of both plays that I am about to see in brief duration from each other. Both, productions, moreover, promise to look at each play’s ‘problematic aspects’ in a ‘fresh light’:

The choice before us too often gets boiled down to either banning or affirming works from the past — a thumbs-up, thumbs-down approach to history. But plays can be recontextualized, their problematic aspects examined in fresh light, their theatrical legacies sifted for new approaches. [2]

Three actors who have played Shakespeare’s Othello, from left: Laurence Fishburne on film in 1995, Laurence Olivier in offensive blackface in 1965, James Earl Jones in 1981. Picture from: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2021-10-20/blackface-othello-lawrence-olivier-bright-sheng

Here, in McNulty’s words, is my burden in this blog. Shakespeare may share, and indeed may have contributed to, the expression of white supremacist racism and antisemitism some find in the play but his position, within that paradigm, is open to interpretation (probably was so even by himself in his own times) and that these interpretations lend themselves to re-contextualization. Shakespeare’s influences and what he did with them are always open to such strategies and personally I would want such strategies to prevail rather than any unnuanced alternative of thumbs up or down to a history that is nevertheless undoubtedly shameful in its effects. Shakespeare lives or dies by the virtues of his dramatic poetry and the character Othello speaks some of the finest of this poetry as if it were revelation of his soul. Full of beautiful contradictions is this poetry. When I lectured on this play at the Roehampton Institute in the 1990s, I used to point to how the words of this man, described by others in the play including himself as a man of action often stilled action as a means of capturing one’s heart with a few words of drama that is as becalmed as is any poetry that reflects continually on itself, like a hall of mirrors in which it is trapped. Is not this, I would say, the most beautiful of lines, whose intention is to calm and still the action of brutal armed men: ‘Keep up your bright swords, for the dew will rust them’.[3]

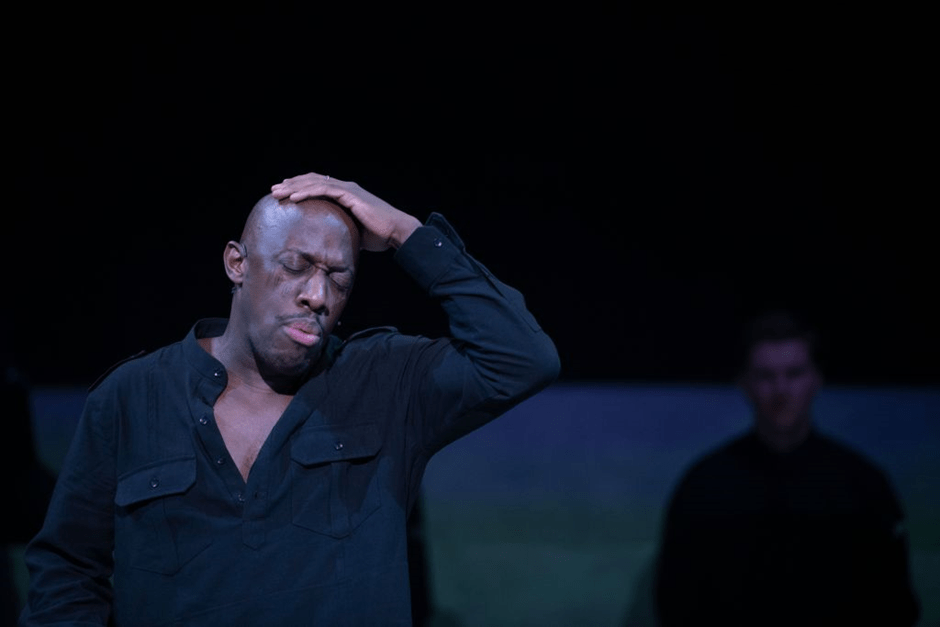

Now, in the production I am going to see, and previewed here, some critics have said the poetry takes second place. It may be this aspect of Othello as a man, who believes so much in his own masculine rigidity (that he mistakes as many men do for rigour), that the director pulled out of Giles Terera, playing Othello. Helen Hawkins, reviewing the performance for the artsdesk.com, dislikes it for playing down the latent poetry of its lines and emphasising the hard brittle man of military business. Terera, she says, ‘doesn’t have much time for what one eminent critic called the “Othello music”’. Yet Hawkins damns with great praise for I yearn to see an actor who can, as she says Terera does, woo ‘with his poetic storytelling voice’, and ‘bark out his early speeches with the brisk precision of a commander’. Moreover, the description by Hawkins that follows this makes me yearn even more towards the performance qualities to be exhibited, wherein she says Terera manifests a man who is:

literally scarred, as we see when he takes off his shirt to reveal the whiplashes he received before he escaped slavery. And he is still snubbed by the powers that be, who here refuse his handshake even as they welcome him as their military saviour.[4]

But surely such actorly style is fully justified by the text. The fault may be in listeners unable to hear the ‘music’ of Shakespearean verse, without the culturally ‘feminised’ lilting of a poetic voice articulating it. Instead Hawkins sees Terera (pictured below) as relishing ‘the physical side of the role — he gives great seizure — and is all soldier, right from his first entry, vigorously practicing martial arts.’

Giles Terera as Othello. Terera clearly relishes the physical side of the role — he gives great seizure — and is all soldier, right from his first entry, vigorously practising martial arts.

And this contradiction in Othello, as a man of supposed macho action whose excellence in the play’s audience’s view lies in the beauty of his words is, as McNulty points out, tied to racial characteristics, as if in deep structural examination of them. For instance, no audience ought not to shudder at this speech:

… Haply, for I am black

And have not those soft parts of conversation

That chamberers have, or for I am declined

Into the vale of years—yet that’s not much—

She’s gone, I am abused, and my relief

Must be to loathe her.[5]

To profess that black people are blessed with being less sensitive and ‘harder’ in their emotional take on private life than white people is one of the most atrocious of racist tropes. Yet, it is a clear untruth, just as is Othello’s insistence of his poverty of emotionally, rather than instructionally, motivated language of the military man: ‘Rude am I in my speech, / And little blessed with the soft phrase of peace;/ …’.[6] I have instanced already how much Othello’s words (even within one line of exquisite poetry) is a language both soft, still, and beautiful: as far from ‘rude’ (in its sense of the words of an unrefined class of persons) as might ever be. You have to instance King Lear to find a dramatic poetry as refined in its rhythmic aliveness as the line: ‘or for I am declined / Into the vale of years—yet that’s not much—‘. Even if we quibble that ‘vale of years’ is a cliché for speech about the aging process, it is redeemed by the rhythmic reversal that follows it, that ignores the cliché and turns on the fact of the man’s ambivalent response to his own aging and increasing unemployment: ‘Othello’s occupation’s gone!’[7]

Let’s be clear. When I spoke about this play in my past career, I stressed that we must approach the play as a monument to British racist attitudinising. It uses the word ‘black’ to denominate skin-colour, and it does this frequently (leading Olivier to create a blackface mask of such an ebony kind that it embarrasses by its stereotypic effect), but also uses it to suggest unadulterated evil, in line with the medieval trope (itself racist) which equated blackness with the devil and deadly sin:

Arise, black vengeance, from the hollow hell!

Yield up, O love, thy crown and hearted throne

To tyrannous hate! [8]

I remember in my early days at Roehampton Institute (now University) teaching an access course aimed at unemployed people of colour underrepresented in higher education. I chose novels that emphasised race such as Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man and Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple but I started off the course with Othello, thus facilitating ways in which racism and /or racist discourse was handled in the classics they would be exposed to on the Roehampton introductory course on the spread of English literature from Sir Gawain to the present day, in which racism both subtle, and much less so, was inevitable. These learners soon picked up the ambivalences of the play – their reactions varying between a kind of pride in the fact that such representations occurred, a horror at the kinds of representation allowable (as in the speech immediately above) and the nuance still left for interpretation. It was the space for re-interpretation which might allow they thought a new anti-racist approach to such phenomena,

One particularly strong individual in that class (I wish I knew what was his fate in British education thereafter – for this was in the early 1990s) pointed out some of the racism in the play comes entirely from Othello‘s attempt to ‘fit in’ with a society that from its very foundations was structured in order to alienate him. He pointed to the following speech in which Othello seems to suggest, very early in the play that as a character he transcended distinctions of race and class. Othello has harboured Desdemona in flight from her father who has pursued them both to Othello’s home, Othello is being urged to hide so he cannot be discovered. The man says, in response:

… Not I. I must be found.

My parts, my title, and my perfect soul

Shall manifest me rightly.[9]

There is no better expression of the view that race makes no difference (though class or ‘title’ may be a different matter) to the worth and value of a man. This may be suitable enougha view in the mouth of Martin Luther King speaking to a black audience about its human rights.

However, in the context of the notion that a hegemonically white state will act fairly to all in this regard, in a way that is sometimes named colour-blind, is patent nonsense. The nature of white privilege is such in fact that it can sustain an idealistic view which abstracts humanity from the circumstances in which it is performed as human behaviour and identity, and which, at least in part, determine it. Othello here seems entirely convinced that the Venetian state will treat him as someone just like themselves with even equal rights to claim superiority over them. Indeed this became the source of a long history of seeing the play Othello as a colour-blind celebration of a ‘noble’ hero; a reading promoted by Othello himself as a ‘man who loved not wisely but too well’.[10] It is an approach still current in online school revision notes to Shakespeare.[11] Yet this fails muster on two accounts.

First, it pretends to a foundation of racial equality that does not exist and attempts thus to marginalise the agency of racism to a few disreputable persons, called ‘racists’, as if they were a class apart from others in a society structured around concepts of white privilege. Second, it oversimplifies racism as an internalised phenomenon which has an effect on those who are its primary victims which we sometimes call self-oppression. For there is plenty of evidence that the latter applies to Othello, not least in attempts to transcend his ‘blackness’. And with that transcendence goes a great many concepts of what makes human behaviour characteristically the nuanced thing it is. For, after all, as I also taught in my old lecture, this is a play about domestic violence against women and its social validation. When I taught the play, I asked learners (much to the chagrin of other members of the English Department who heard the lecture) to think about it in the context of Elizabethan domestic tragedy, which though traditionally a form attached to bourgeois family life, offered a view of how power is structured in everyday life from the point of view of women and their oppression.

And Othello himself makes it clear that his retirement from war is to a view of domestic life he not only idealises but misrepresents as peaceful in itself, as in this comment to the brawlers which include Michael Cassio, the soldier he will accuse of cuckolding him, for disturbing a ‘private and domestic’ realm with conflict he believes to be alien to it and to be ideally safe and protected by men doing their duty.

… What, in a town of war

Yet wild, the people’s hearts brimful of fear,

To manage private and domestic quarrel,

In night, and on the court and guard of safety?[12]

Shakespeare I think makes it clear (to me at least) that Othello’s absurdly unrealistic and dehumanised (because initially idealised) view of the nature of women is the source of his later heinous views of the ignoble animal character he seems to attribute to women later and which justifies the murder of his wife, Desdemona. The bifurcation of women by a patriarchal society as ideally noble and spiritual but otherwise animal and degraded (a patterning usually called that of the ‘angel and the whore’ in feminist literary analyses) is the same bifurcation he is forced to live as a black man in white society, an ideal tool of the state or an animal savage.

So, apart from giving me chance to reminisce, why do I think rehearsing all this about my past interactions with this play helps in thinking about seeing the new National Theatre production in a couple of weeks? Akbar’s Guardian review argues that the play as performed in this production by Clint Dyer, a black director, (and mirroring a less subtle articulation of the point by Helen Hawkins, who tells us that Dyer himself emphasises the role of misogyny in the play more than racism) is novel because it seeks out that aspect of the play itself that:

… is about the tragedy of domestic violence. The women are not reduced to victims here while the men, including Othello, are controlling, toxic abusers. It is an almost obvious interpretation, once we have seen and heard it, yet it makes the play feel utterly new.[13]

‘Never simpering or scared’ … Rosy McEwen as Desdemona, right, with Giles Terera (Othello) at the National. Photograph: Myah Jeffers (picture and caption from https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/dec/01/othello-review-clint-dyer-national-theatre )

And with this view, I wholeheartedly agree. What must follow then is seeing if this production delivers in this way and makes the intersection of racism and sexism in it open to an audience, as it was to Akbar, at the very least, although she casts seeds of doubt herself by also saying in her review that the production ‘does not seem entirely joined up in its vision’. She praises most the actors playing Emilia and Desdemona as cross class boundary representations of domestically abused women. And though she senses that the director’s ideas suggest the analogy between, and complex interaction of, racism and sexism, she seems perturbed by messy mixes of genre between the machinery of Greek tragedy (there is a chorus in this production she informs us) and modern melodramatic thriller. To me this sounds perfect since perfection for me is that which shows most clearly that the joins between things are in fact and reality nearly always more fractured than we like to think. Helen Hawkins has I think thought more deeply about how racism and sexism interlink in the values of the production itself and I yearn to see how I respond to this aspect of the play which Hawkins thinks may justify and create new meaning in the play with the use of a chorus in the style of Attic tragedy. Of the intersectional analysis of racism and misogyny, she says:

Dyer suggests the two forces are united in a kind of fascistic groupthink, which he represents with a chorus he calls the System, consisting of all the cast bar the three leads. It appears, masked, around the main action and gestures and poses in unison in response to the text. When needed, actors slip away to play their roles and return to the others at the end of their scene. As a way of suggesting darker inchoate forces, a mob mentality, this conceit goes some way to giving the production a core.[14]

Yet again though Hawkins suggests something missing from the production to drive home its novel approach. There is nothing but a previewer to do with this than wait, see, and then assess. We will see soon enough.

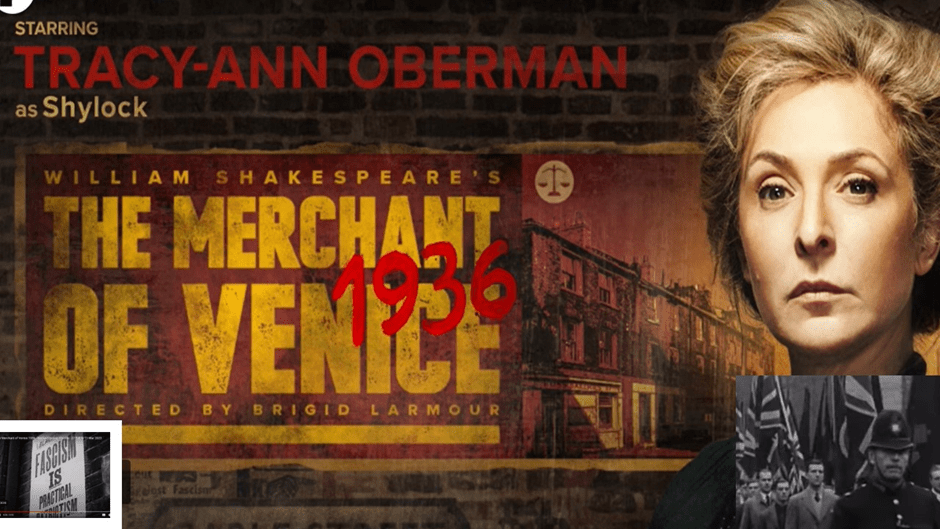

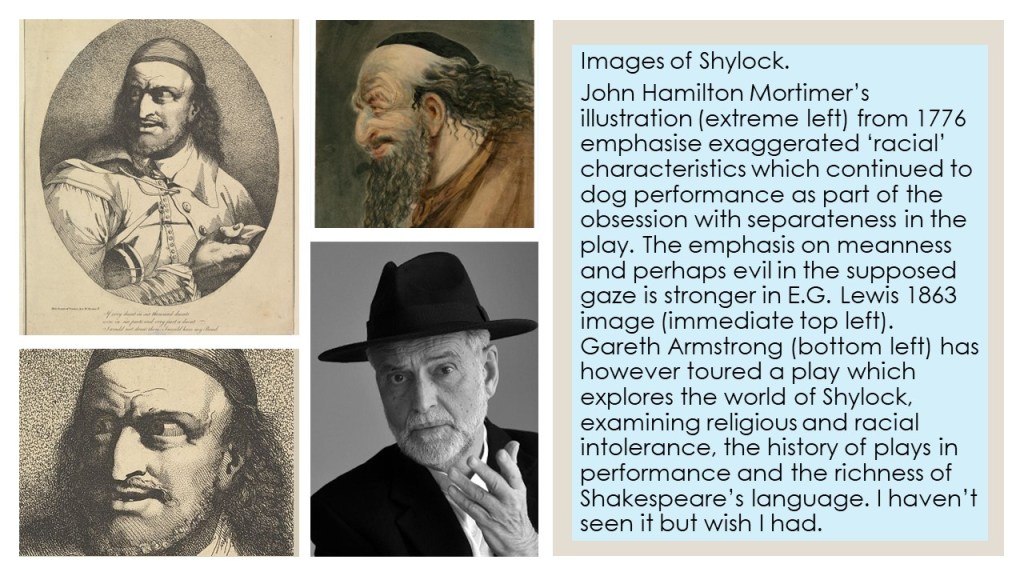

Two weeks later, I go to see The Merchant of Venice at Manchester. I have already blogged about this. However, I return to it here, precisely because McNulty makes the point above that this play that it is even more baldly and problematically racist. The character of Shylock is after all built on tropes that negate personality – a character that not only shies away from sight (‘I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you,’ he says)[15] but is also literally and metaphorically locked up (‘There are my keys, … Look to my house’[16]).

Moreover, we Northern folks have less to help us to see how the Watford Palace Theatre production deals with problems in the play, for unlike the National Theatre’s productions, provincial (even for a town as near London as Watford) and touring theatre gets less accessible coverage from critics thought worthy of being individually named – the London centric nature of British theatre is surely a remaining problem for those of us north of Watford Gap service-station on the M1, and this possibly, in this case, includes Watford itself. Yet again the play is undeniably racist, even if it also challenges racism.

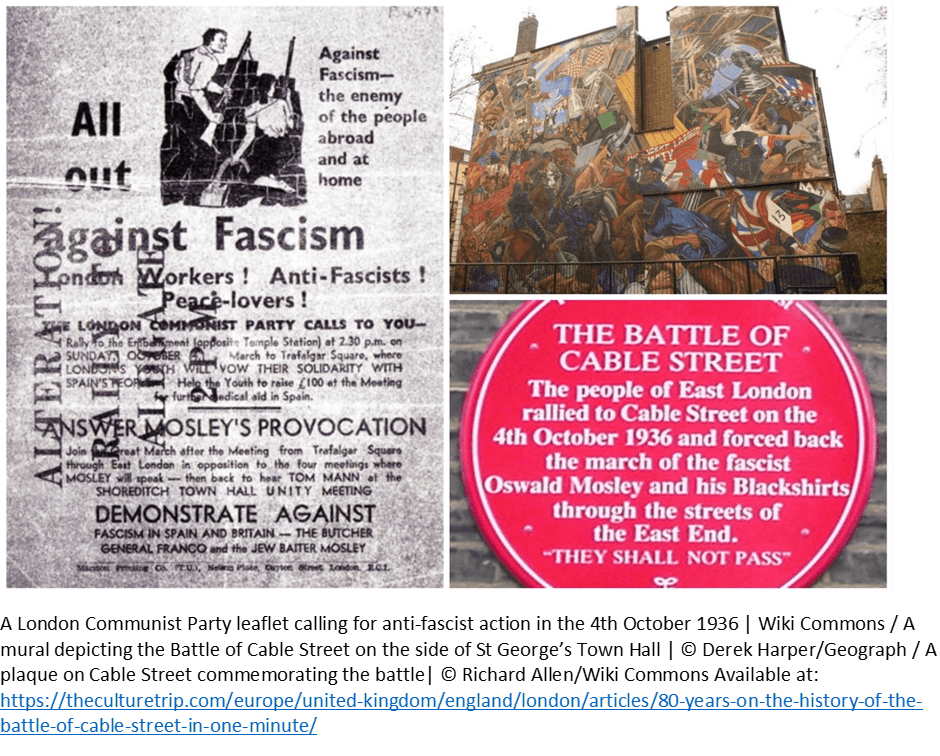

A review in Theatre Weekly does at least show us that Tracy-Ann Oberman, who plays Shylock in this production, has used her own family’s history to emphasise the more the fact of antisemitic racism (in Russia and the East End of London) and resistance to it. This The Merchant of Venice 1936 is set in Cable Street and uses the Cable Street rising against the permission given by British Government to Oswald Mosley to parade his Fascist blackshirts, with Union flags aflutter, through the East End home streets of Jewish people on the 4th October 1936. In this re-telling Shylock is an East End matriarch based on Tracy-Ann Oberman’s grandmother, who escaped Russian pogroms. Portia and her circle are aristocratic members of the British Union of Fascists under Mosley and the locked ghetto in Venice in the text is replaced by ‘East End Cable Street, with pawn shops and money- lending under the counter of shmatter stalls, and seamstress jobs’.[17]

There is a chance here perhaps that Shylock’s hardened nature, patriarchal to a fault, will be entirely lost from the play but I doubt that. Rather it will be reinterpreted; since it is easier, perhaps, in misogynistic cultures to emphasise the subjective lives of apparently ‘hard’ women than of hard men, like Shakespeare’s character. The play after all makes it is abundantly clear, that in this case at least:

You may as well do anything most hard

As seek to soften that than which what’s harder?—

His Jewish heart.[18]

Shylock certainly lays the ground for us to see that the hate he, as a Jew, owes to Bassanio might be well-founded. Though Antonio borrows from him, he does not refute the fact that had spit upon Shylock in the street, much as Mosleyites did in the 1930s and as Anti-Semites still do, if perhaps metaphorically more than literally. Yet Shylock is not given Othello’s music to say so. The verse is bald and mean, without the nuance awarded to Othello:

Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated me

About my moneys and my usances.

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug

(For suff’rance is the badge of all our tribe).

You call me misbeliever, cutthroat dog,

And spet upon my Jewish gaberdine,

And all for use of that which is mine own.

Well then, it now appears you need my help.

Go to, then. You come to me and you say

“Shylock, we would have moneys”—you say so,

You, that did void your rheum upon my beard,

And foot me as you spurn a stranger cur

Over your threshold. Moneys is your suit.

What should I say to you? Should I not say

“Hath a dog money? Is it possible

A cur can lend three thousand ducats?” Or

Shall I bend low, and in a bondman’s key,

With bated breath and whisp’ring humbleness,

Say this: “Fair sir, you spet on me on Wednesday

last;

You spurned me such a day; another time

You called me ‘dog’; and for these courtesies

I’ll lend you thus much moneys”?[19]

How clearly the statement ‘you treated me as a dog’ is made to seem repetitively whining, sarcastic rather than dignified and unpleasantly hard in the justification of vengeance, unnamed but to come, for wrongs done. It is the language of threat and not designed to gain empathy for its speaker. Othello would never be given verse like this, for its character as speech belittles they who speak it. Perhaps then this play is irredeemably racist. However, Oberman is cited in the same piece in Theatre Weekly as saying:

“I’ve always wanted to reclaim The Merchant and wanted to see how it would change with a female, single mother Shylock. My own great grandma and great aunts were widows, left in the East End to run the businesses and the homes, which they did with an iron fist. …”.[20]

It would seem from this that a female Shylock will rattle out such speeches from an ‘iron fist’ inculcated in her by a racism so severe that it might ask us to see behind the unpleasantness of the exteriors of speech in verse. I am interested to see how this will happen. For instance, how will the production deal with the meanness of Shylock over giving food to his dependents, which lead him to chastise not only his servant, Launcelot Gobbo (who is not in this production) for overeating but also his own daughter, when he warns her against socialising with Gentiles:

Well, thou shalt see, thy eyes shall be thy judge,

The difference of old Shylock and Bassanio.—

What, Jessica!—Thou shalt not gormandize

As thou hast done with me—what, Jessica!—

And sleep, and snore, and rend apparel out.—[21]

There will be hard work to do not to make Shylock look, as he does to the Christians in the text, mean then except that casting them his Christian opponents as blackshirts will give entirely different context and emphasise the bias in their speeches. Enacted dignity in Oberman’s Shylock may be enough to counter the racism of the Venetians who say things like:

I never heard a passion so confused,

So strange, outrageous, and so variable

As the dog Jew did utter in the streets.[22]

For dignified emotion performed credibly can easily be seen by people without emotional intelligence as ‘strange, outrageous, and so variable’. It will be tested, as in productions of this play it always will, by how well the actor playing Shylock delivers the central speech of Shylock about the effects of antisemitic bullying, marginalisation and oppression:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge! The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.[23]

The attitudes audiences leave with from plays they see are determined in part by attitudes they bring into the play and partly by their reception of seeing a performance of these and counter-values in the production. I am looking forward extremely to seeing how The Merchant of Venice fares under the bold revisions of the Watford Palace Theatre production for, as McNulty says, it is ‘a work even more heavily freighted with controversy’. It would appear that this production’s director, Brigid Larmour, believes that we might only rescue the play by changing its context to a more modern one, causing the English in particular to challenge the cherished notion of Britain ‘standing alone’ in 1940 by reminding ourselves that we may have forgotten ‘how much support there was for fascism in Britain in the 30s’ and how closely this is linked to the living memories of Jews such as Tracy-Ann Oberman. “It is dangerous to forget,” Lamour says but equally dangerous is it to forget how deeply ingrained into British, as other Western cultures, is antisemitism: ingrained even by its admittedly great cultural heroes like Shakespeare, and indeed Dickens.[24]

Watch this space though for updates after seeing these productions.

All the best & love,

Steve

[1] Arifa Akbar (2022) ‘Othello review – Clint Dyer makes this tragedy feel utterly new.’ In The Guardian [online] (Thu 1 Dec 2022 06.01 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/dec/01/othello-review-clint-dyer-national-theatre

[2] Charles McNulty (2021) Commentary:’ Must Laurence Olivier’s blackface Othello be banned? I showed the film and wasn’t canceled (sic.)’ in The Los Angeles Times (online) OCT. 20, 2021, 10:02 AM PT . Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2021-10-20/blackface-othello-lawrence-olivier-bright-sheng

[3] William Shakespeare Othello (I, ii, 78) Available in full text: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/othello/entire-play/

[4] Helen Hawkins (2022) ‘Othello, National Theatre review – ambitious but emotionally underpowered: Clint Dyer’s new take makes Othello a victim of mob mentality’ in the artsdesk.com (online) [Saturday, 10 December 2022] Available at: https://www.theartsdesk.com/theatre/othello-national-theatre-review-ambitious-emotionally-underpowered

[5] Othello op.cit: III, iii, 304ff.

[6] ibid. (I, iii, 96f.)

[7] ibid: (III, iii, 409)

[8] ibid (III, iii, 507ff.)

[9] ibid: I, ii, 36ff.

[10] ibid, V, ii, 404.

[11] See, for instance, https://schoolworkhelper.net/shakespeares-othello-as-a-tragic-hero/

[12] Othello op.cit: II, iii, 227ff.

[13] Akbar, op.cit.

[14] Hawkins, op.cit.

[15] William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice I, iii, 36f. As in online text available at: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/the-merchant-of-venice/entire-play/

[16] Ibid: II, v, 13ff.

[17] Theatre Weekly (staff writer) (2021) ‘Tracy Ann Oberman, currently appearing in the major BBC1 drama about British Fascism in the 1960s, Ridley Road, will reinvent the role of Shylock in a major production of The Merchant of Venice’. In Theatre Weekly [October 20, 2021] Available online at: https://theatreweekly.com/reimagined-the-merchant-of-venice-to-tour-in-2023/

[18] The Merchant of Venice op.cit.: IV, I, 79ff,

[19] ibid. I, iii, 116ff.

[20] Cited Theatre Weekly op.cit.

[21] The Merchant of Venice’ op.cit. II, v, 1ff.

[22] Ibid: II, viii, 12ff.

[23] Ibid: III, I, 52ff.

[24] Theatre Weekly, op.cit.

2 thoughts on “The ‘Elephants in the Room’: racism in the British artistic ‘heritage’. This blog written to prepare me to see new productions of ‘Othello’ (National Theatre Live streaming 23 February 2023 at Gala Theatre Durham) and ‘The Merchant of Venice’ (Watford Palace Theatre tour at Home theatre, Manchester 16th March 2023).”