Speaking of an early short story in an interview with Deborah Triesman of The New Yorker in 2018, Taymour Soomro says: ‘Power is such a traditional expression of masculinity, which is why the power dynamics in relationships between men fascinate me’.[1] This blog examines a great new novel, and heir to Turgenev, that examines the role of power of all kinds within male inter-relationships – familial (including chosen familial), memory (including erotic memory) and their experience in the present. The blog is about a book that ought to be a Booker winner: Taymour Soomro (2022) Other Names for Love London, Harvill Secker.

Taymour Soomro and the shadow of powerful men.

When Deborah Triesman interviewed Taymour Soomro for The New Yorker in 2018, he talked of a short story also published by the same magazine. I haven’t read this story but the power distinctions in the relationship of the characters whose tale is told seem to be quite clear in both the interviewer’s and Soomro’s comments. Triesman says:

Amer is gay and becomes very interested in a boy—or a young man—who has a shoe-repair stall in the street. In his pursuit of the boy, how much of an obstacle (or advantage) is their difference in social status?

One of the points Soomro makes in answer is that: ‘For Amer, the difference in social status is an advantage. It allows him to feel a little superior perhaps, allows him to feel that he has authority’. But more importantly he elaborated this in an answer to a further question in ways that obviously point to some of the issues in the novel we are considering now.

Power is such a traditional expression of masculinity, which is why the power dynamics in relationships between men fascinate me. Here, the ways in which each is powerful are what attracts one to the other but ultimately, Amer’s assertion of authority over the boy is what (spoiler alert) destroys their relationship. Amer certainly crosses a line but perhaps he feels compelled to behave in that way in order to signal to himself that he is powerful, that he is worthy of being his father’s son.[2]

The point I put in bold already indicates that, in relationships between men, the constituents of the relationship that are masculine do not reference an interaction between two men alone. Of course over and above the dyad of two men an abstract ideology or ‘patriarchal tradition’ of inherited masculinity operates but this is not all that is meant here; the fact is that these relationships are not just dyads because each man’s relationship to the other is mediated by their respective relationships to their fathers; shadowy figures who set standards as part of the price of their continuing attachment – even over distance or after their death.

This paradigm of male relationship is even more apparent in Other Names for Love. In an interview with Alex Preston for The Guardian in June 2022, asked about what he has on his bedside table for reading, Soomro answers: ‘Fathers and Sons by Turgenev. I’m rereading that’.[3] Turgenev’s novel is the classic study of the relationship between father and son as the means by which history is primarily experienced by those men who are privileged and hence powerful in the moment of the current status quo. Moreover, father-son relationships, as they change in time, inbuild the dynamic of history’s progression from the status quo to something, for good or bad, new that also must be played out as the stuff of history. Indeed this is a classic trope, as findable in Hamlet as in Turgenev.

To mention Hamlet is, of course, to emphasise the obvious point that a dyad involving a man and his father is sometimes a matter of negotiation with historic time and mutability. In the play of that name, old Hamlet the father is already dead when the play opens, such that the relationship between young Hamlet and others is mediated only on rare occasions by a ghost but otherwise mainly through memories of that figure:

… Remember thee?

Ay, thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee?

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial, fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there,

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter.[4]

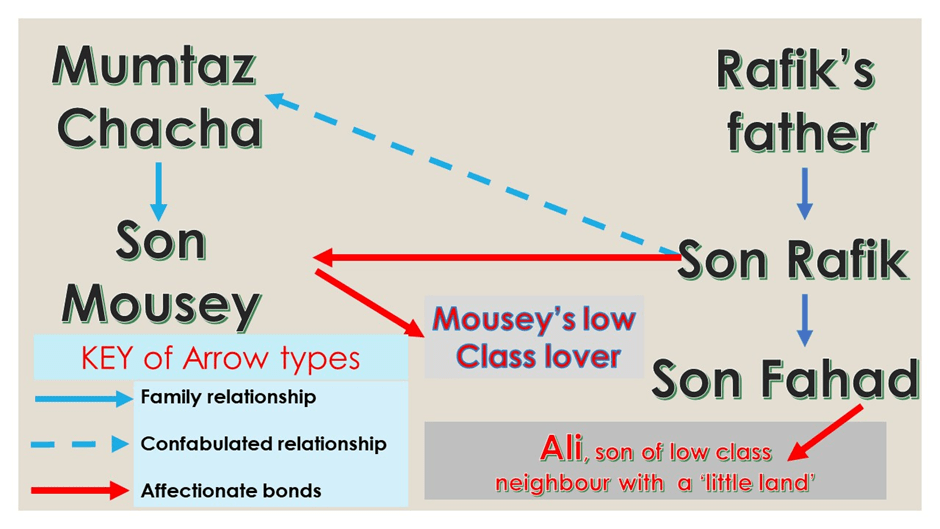

In Other Names for Love there are many fathers and sons, relationships including some dead ‘fathers’ like Mumtaz Chacha, the patriarch and landowner. The memories sons (or people who hold the place of sons like Rafik with Mumtaz) have of such fathers hold active agency on their lives. This relationship becomes even more complex when the man who is a son forms a relationship with another man as does Rafik with Mousey or Fahad, Rafik’s son, with Ali. Rafik, we need to remember, is not Mumtaz’s son but here the novel shows us that a cousin might, in some circumstances, claim the rights of a ‘lost’ son; become the genuine son’s substitute, as Rafik does with Mousey when the latter is lost from public record (in distant London) for reasons suppressed. It is hinted that Mousey loses face in traditional Pakistani society because he is gay and Rafik must, in the course of this novel, acknowledge that possible fact in his treatment of Mousey’s male servant-lover after Mousey’s death, just as he must in parallel acknowledge his own son as a gay man. Mousey’s fate, that is, is confounded with that of Rafik’s own son, Fahad. Though Mousey’s relationship to other men throughout remains shrouded in the unspoken of history, Fahad has, by Part III of the novel (helped by the direction of history’s recognition of the existence of queer men in public life) semi-publicly acknowledged his status as a man who loves only men romantically and sexually and who chooses to live only with a man. The surprise is that it seems that Rafik has accepted Fahad as a gay man too and this is even before we (and Fahad) know that he treats Mousey’s male lover with empathy and respect after Mousey’s death.

Fahad and Mousey’s stories are so parallel to each other that they become totally confounded in the mind of Rafik, by aid of the confabulations which substitute for his memory as his dementia progresses through Part III of the novel. Both Fahad and Mousey are in some small way belittled physically, and infantilised or feminised, as though both these were codes for male inadequacy. Such codes, in relation to women at least, are not reinforced by events in the novel however for Fahad’s mother, Soraya, has motherly authority that is as strong a force as the paternal variety of it in Rafik through the course of the novel. However, when in the final chapter, Rafik looks in the ‘rearview mirror’ (a beautiful metaphor for memory) of the car he travels in, he seeks to see ‘the boy’ we know to be his son Fahad in the back seat (Fahad, we will note, becomes continually reduced to category as if exchangeable for another ‘boy’). Not finding him in that mirror’s scope, he says, ‘We’ve forgotten him’. Turning physically to look back, a stronger motif of memory, confabulation and /or hallucination take overs Rafik’s perceptions: ‘When Rafik turned to look again, it was Mousey twisted into the corner, in a gaudy shirt, chains round his neck and rings in his ear’.[5] Mousey, coming back into the novel as a ghost (or hallucination) from past time is coded as gay, as he was sometimes in his life, by normative perceptions of his ‘oddness’ reflected as from a mirror by his chosen clothing.

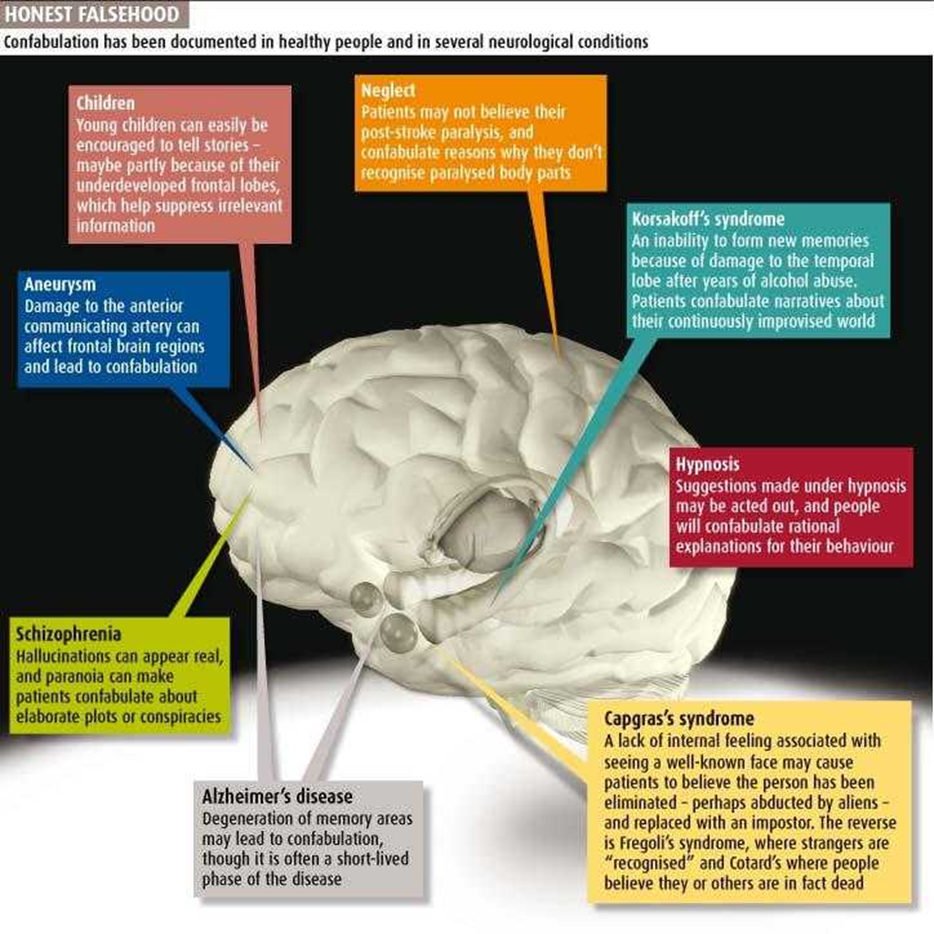

Before proceeding in this argument however we need to know why and how this novel tackles the perspective of a person with dementia, and dementia’s effects on memory with some of the terminology of its ‘symptoms’, since I have invoked them already. The symptoms of dementia, if that is what they are, accumulate in Rafik in Part III in progressive stages through that part of the story: they include phenomena such as palilalia, repetition of the same words or point (especially in describing the files of his past life events that he hands to his son), ‘wandering’ (physically and in speech) at times of the day considered inappropriate such as the night, perceptual difficulties – auditory and visual, misrecognition of persons and faces, and confabulation, wherein the person who forgets an incident feels the necessity to invent a story to explain their current situation, a story that they themselves believe to be true for they are most often the primary audience of their own confabulations.

Confabulation however is not the reserve of persons with dementia or other neurological ‘insult’ (see figure illustration above). Mark Solms , the neuroscientist and psychoanalytic thinker, defines it thus: ‘filling in gaps in one’s memory with false narratives and memories about the self or the world (a type of misremembering) …’.[6] ). Confabulation is not then just symptomatic of dementia, where even there it serves a defensive function (to deny the dementia’s effect), but a phenomenon used in the psychology of everyday life. This usage can be explained partly because humans so rarely appreciate the size of the role forgetting and fabulous reconstruction involved in shaping our stored memories or used to cover over the fallacies common in everyday perception. This is why, when asked what he remembers at the end of the novel, Rafik’s answer is so poignant, for it is understandable by anyone who thinks at all about how their experience of memorial cognition of the past is formed:

‘“Sometimes you don’t know what you remember and what you think you remember. Sometimes even my father’s face, when I remember it, it is one way, sometimes another”.[7]

In this novel, with its constant shifts of narrative perspective or ‘point of view’, confabulation plays a great part. In some ways it explains the shifts from Rafik identifying his son, by his proper name, Fahad, to merely calling him the boy’, since the category stays in memory longer than its unique exempla. If the term belittles, it also explains how in the guise of ‘the category ‘the boy’ Rafik can so easily slip from perceiving Fahad, his son, to perceiving in the former’s place, a memory of Mousey, since both are important ‘boys’ to him. But it also explains how Rafik structures his love around the assertion of his own power and authority, those things that are asserted in both senses of patriarchy, the power of a father and that, simply, of a man.

The book opens with Rafik’s ‘shouting instructions’ and being heard against all barriers and at distance so that Fahad, here aged 16, ‘flinched away’.[8] The orders can be gentler but remain commanding, and require Fahad to be seen as ‘the boy’ rather than an individuated person: ‘In the evening he sent for the boy. “Sit,”, he said’. Within a page of the latter example, the focus of Rafik’s story of his memories shifts from instructing his son taking ownership of the manly authority and power his Dad is transmitting to him to bolstering the sense of Rafik’s own present power. That is because Rafik’s power and authority in Abad, his estate, is fading since his tenants ‘see the way the wind blows’ and are shifting their allegiance to an alternative landlord and master. For this reason, he tells Fahad that fathering him, ‘a boy’ was proof of his sexual and manly potency (the doctors having said ‘everything down there is okay’ (that is, that he is not sterile)). For sexual potency is the biological myth of male power’s origin in patriarchy:

“… Even when you were born, they called to tell me, I heard them say, “It’s a daughter.” Of course they didn’t say it, but I was so sure. I had made up my mind, that was what I heard. Then everyone kept saying, “Mubarak, it’s a boy.” And look now. It’s a funny thing.”

Blessed (Mubarak),Rafik certainly is. Although the term is perhaps another name for Rafik, it clearly has a primary symbolic meaning here. In patriarchal thought the birth of a boy (not a girl) is a sign of being blessed with the power and authority in himself that he needs desperately to believe in. Without overt signs of such power, it must be confabulated. This is subtle work in a novelist.[9]

This story of Fahad’s blessed birth even surprises Rafik when he finds himself telling it’s story but it also becomes yet another burden on Fahad as his son, who throughout doubts his own ability to be the ‘man’ in a relationship with either father or a male lover . For the former being a ‘man’ means partly being able to take on power as landowner and government minister, for the latter, perhaps, it is being the ‘dominant’ partner in a gay relationship lover (his choice of the dominating, and physically unprepossessing, Englishman Alex as a partner later in his life surely can be explained in this way). Without using them as a simple binary code for power and powerlessness (for this novelist is too subtle – he knows this simple binary lives in the culture and must be recognised though not endorsed). Fahad is sometimes typed as girlish, by his manly friend Ali, when both are 17, and is to become his short-term lover: Ali has‘big hands, broad shoulders, animal eyes that flashed under his heavy brow’.[10] Ali sees Fahad sometimes as a brother, sometimes as a sister; his ‘prettiest sister’ hopes Fahad. This reflects, I think, on how Rafik also saw Mousey in the past as a cousin whom he also confabulates as a brother – sometimes to readerly confusion, but thus is confabulation.[11] But it’s also clear (to me at least) that Soomro does not endorse this play with gender-roles as absolute truth for even the ‘tough, local sort’ (as to near to a working-class boy as the novel gets),[12] Ali, for instance, gets absorbed in sex/gender roleplay in reading to Fahad from the latter’s disguised sexually romantic novel. When they read aloud together in the short passage from the novel following, not only reading roles are exchanged by the boys (since each qualifies to be nominated by the categoric term, ‘the boy’ (for reasons I hinted at above)) and it is unclear which boy is feminised and to whom (hence the passage’s ‘perversity’):

There was a perverse pleasure in reading that, while the boy sat there brooding like an ox. He wanted to read aloud. “She touched her hand to his chest,” he wanted to say. … He wanted to make the boy blush. The boy had a strange mouth – dark lips with an exaggerated Cupid’s bow, almost girlish, really the wrong mouth on the wrong face.[13] (my italics)

The name of that romantic novel read out aloud by ‘the boy’, by the way (it is from Fahad’s mother’s bookshelves – and she too is a uneasy reader of romantic novels for such a powerful woman) is Dark Obsession: A Passionate Story of Love Overshadowed by Memories of the Past.[14] So apt that title is, for it is meta-satiric of the themes of this weighty book (in quality if not quantity weighty) of Soomro’s. It sources the romance of Ali and Fahad but also undermines it – the past of Pakistan landowning having such a thick shadow.

Not Fahad’s novel, I think, but the title is ubiquitous in Google searches

Of course what makes a man ‘a man’ is an important theme of the novel as with the short story we started with and it is partly, if not only, to do with the long shadow of fathers in the lives of sons, even when they fall in love with other men. At one point the phallic quality of the power of the gun is invoked to symbolise that power but this coding is rejected by Rajik: ‘“A man who needs a gun, what power does he have?” his father said. “Only as much as the gun.”’[15] Rafik feels sure, when he isn’t doubting himself as he also does, that masculinity is birthed by a relationship, almost feudal, to the land that one owns: as he views that land ‘his heart swelled with love, with pride, with duty – yes, duty – to be here’.[16] For feudal landlords duty may have meant sitting in a palace being charitable to one’s peasants and taking on the regalia and duty of administration of locality and nation but in the emergent capitalist era of Pakistan it also means clearing forests, providing appropriate irrigation for imported profitable plants and sometimes damming up that irrigation that also waters a competitor’s fields to win economic prizes; competitively indeed if unfairly.[17]

Yet again some men find a relative power in their bodies – in their capacity for labour or merely in their butch appearance, for Ali’s body is as ‘sturdy as the trunk of a tree’. Yet in challenging Rafik for power in an election, Ali fails and is squashed politically, forced to sell up this family’s small lands and petrol pump and move locale. Ali is, after all, the beginning in Pakistan of an almost democratic basis for political power rather than feudal one and thus is fated by history to begin the challenge to Rafik’s authority as a privileged landowner. And likewise what is challenged is the implicit notion of what constitutes masculinity for Rafik. As Ali says, what makes a man, for him, is the ability and capacity of a person to make choices and follow them through into effective action, something not possible if an elite hold all the power and authority there is to have.[18] It is a lesson that is learned ultimately though by other men than Ali, such as the wily Muhammed. The latter ensures he outwits Rafik before he makes a move to challenge his power by repeating Rafik’s own actions, against Mousey, from an earlier time, of damming up the irrigation channels that once fed their respective challenger’s prosperity and power. Muhammed, the challenger of Rafik who eventually brings the latter down in a deal for the land, you might notice, is mistaken by Fahad for Ali when Fahad’s glasses are broken in a car accident, and having made that perceptual error he confabulates according to the narrative hope of his desires. Yet as Mohammed steps to embrace Fahad: ‘he became someone else entirely. It wasn’t Ali at all”.[19]

If what makes a man is debatable and contingent on personal, national, and global history, this is precisely what makes the unlikely Alex (Fahad’s male partner with the paunch showing through his silk shirts) powerful, not only in international capitalist enterprise but as the dominant partner in his domestic relationship to Fahad. But the contest between man and man for power and authority is replicated throughout the novel, though often ill remembered and covered over by confabulation. At its root in the family is the suppressed love-hate relationship between Rafik and his cousin, Mousey, for the power and authority of Mousey’s father and Rafik’s uncle, Mumtaz Chacha: ‘Tough as nails’, and ‘A man’s man’. In contrast Mousey has bookish ways and is obsessed by (Western) arts. Mousey’s character is either feminised or infantilised by his own nickname and by rumour based on his appearance as being slight and unmanly: Rafik speaks softly to him and squeezes his knee when both are adult as you would a young boy. [20]

Moreover, Rafik’s ambivalence about Mousey, as man and possible inheritor of power and authority (for Mousey is Mumtaz’s true son), is reflected in the structural analogies between Mousey and Fahad; in the way, for instance, the relationship between Ali and Fahad mirrors that of Mousey and Rafik. This is true even of how both relationships end with the victory of the economically stronger male partner (Rafik and Fahad – like father like son in that respect if no other as Fahad claims at least (‘I am not my father’)). Both economically stronger men, as I have called them, end their relationships (in as far as they can and although they may not acknowledge this reason consciously) because they each find themselves and the basis of their power and authority challenged in those relationships, even by their love for the other man: Rafik for cousin/brother Mousey, Fahad for Ali. For instance, Ali significantly says Fahad looks ‘like a lion’ but is ‘a mouse’.[21] And Ali is the man who almost tells Fahad of the rumours of Mousey’s sexuality, rumours Fahad will turn for himself into an open identity as a gay man.[22] Bullied as a gay man (‘It wasn’t such a queer thing but people talked and made up stories and a name for Mousey’ is the extent to which that identity is bruited), Mousey had been sent to London by Mumtaz Chacha. Fahad in contrast chooses to go to London for it is his powerful mother’s world and that of the Western arts. The structural analogies in the novel can, I think, be drawn as a diagram and I attempt this at the very end of this blog.

However, we might guess that Soomro thinks this structural analogy applies to himself too. For though he sees the parallel of his own story with Fahad’s he disclaims an exact fit, especially with regard to his grandfather, whom he describes in the book’s ‘Acknowledgements’ as ‘a politician farmer, but there the similarity ends’. He says more about this grandfather as model for father Rafik in his Guardian interview with Alex Preston. For this grandfather took him onto his farm and taught him to manage an estate, having failed in a bid to be a novelist on his first attempt. There are other parallels though, In the same interview he describes his own stereotypically gendered ‘girlish’ reading which mirrors that of both Mousey and Fahad. He says:

At home in London I’m in an apartment where we have all of the family books – my parents’ books and my sister’s books. We all read a ton. The joy of that is that the bookshelves are full of books that I haven’t read. My father’s books tend to be a lot of nonfiction and biography, whereas my mother and sister read fiction. It’s very stereotypically gendered.[23]

Taymour Soomro at his home in Kensington, West London. Photograph: Karen Robinson/The Observer

Soomro makes it clear in the same interview that he intended to write openly:

about queerness in Pakistan for so many reasons, including making visible experiences like my own in Pakistan, and challenging reductive narratives about the country – narratives about Muslim barbarism and homophobia. Homophobia was a Victorian export to South Asia during the empire, that’s when these laws date from. And like so much law in Pakistan, it does not always correspond to custom, certainly not neatly.

This is why, I think, Rafik must relearn his love for Mousey through his son, because, as Soomro knows so well the accusation of homophobia against Muslim groups is often merely disguised racism. But his greatest achievement is that he engineered the novel so that its parallel stories have the dynamic of history – a history pf Pakistani national politics as well as of shifts in the grasp of male power and authority. He tells Alex Preston that the story falls into parts, separated by time lapses wherein characters and nations age, and sometimes die, migrate, or get married, as Ali does. He says yet again:

I thought, why don’t I separate the novel into parts so they feel like novellas? It also engaged with the way I wanted to tell the story. I wanted to show these men at very different stages of power in their lives.[24]

Stories in the novel illustrate then the ‘different stages of power in men’s lives’. This is my point. Moreover, they do so not merely in a chronological series; for the dynamics of social power in lives is also a means of handing power back to the progressive processes of history, of not holding onto it forever to everyone’s detriment. Hence the need to discuss memory, the means of grasping history. When Fahad returns to Abad, the farm, he wishes to find Ali again, and find him as he once loved him and not in the way, a way he had conveniently forgotten and covered over with confabulation. What he finds instead is that Ali has moved on to a point of no return. Hence he can say to Fahad on their brief telephone call, “It’s good to remember”, but when told of Rafik’s dementia, he calls it a blessing since it allows the powerful man to forget ‘the things he’s done’, even the vengeance against Ali himself. Fahad has even forgotten his own prompts to his father in that role; only to rediscover the facts in preserved letters of Fahad in Rafik’s files. Has he also forgotten, as Ali says he has done deliberately, his brief lovemaking in the jungle?: ‘“As if he’s dead” I told myself. “Think of him like this”’.[25]

Forgetting may be kinder than memory when people ought to move on. Hence the folly of Rafik’s desire that Fahad write up his life as it is – in the files he can no longer read himself. He can, in a confabulating manner, believe this will “set the record straight” because “People forget. They say all kinds of things”. However, there is also a desperation in his wish, in the belief so beloved of people who wish to maintain the status quo by holding on to a take on history that privileges only them: ‘“Once it is written” Rafik said, “once it is history, no one can question it”’.[26] But history is too often about who holds power over the means of production, and in this novel the means of production are those of agriculture – the making of food, from ‘rice’ (that ‘staple’ food) in the new paddies of Rafik and Mousey, to the sumptuous foods of a government minister’s private railway. Eating a feast on the latter, Rafik can afford to feel he deserves luxury and say “What do I care about power? Power is not something one pursues. Power pursues the man”.[27] But Ali knows better – offering to share with Fahad his simple biryani, better than that served in Fahad’s father’s palace, he says of Rafik that he uses food provision to local people as a ploy, precisely to pursue power: “He wants them to see who the important man is, who gives them food,..”.[28]

It’s this perception that means that Fahad must abandon Ali at the very moment that they fall into erotic union and the promise of love. For Ali can and will challenge the power of landowning lords and their capital. After sex in the jungle ‘they drifted apart somehow, as though they had been one and now became two’.[29] For power does not pursue man. If you want to keep it, you have to fight, Fahad realises at some deep level, and his moral fate as a man who uses other men is sealed. Not long after he will abandon Ali in Pakistan for a life in London with a richer man, whom he does not, and cannot, love. It is a wonderful novel and I can’t leave it without leaving also a small diagram of some of the parallels in relationships, including familial and erotic power relationships and unions it illustrates. Of course a simplification, I hope it helps. But better still read the novel for yourself without the spoilers in my blog. Then if you will, consider my blog.

This is a rich novel and I have not covered all it offers, even in my own poor estimation. It should win a Booker, but I am not holding my breath.

Love

Steve

[1] Deborah Triesman (2018) ‘Taymour Soomro on the Sights, Sounds, and Social Dynamics of Karachi’ in The New Yorker (online December 31, 2018). Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/books/this-week-in-fiction/taymour-soomro-01-07-19

[2] ibid.

[3] Alex Preston (2022) ‘Interview: Taymour Soomro: ‘I want to challenge reductionist narratives about Pakistan’ in The Observer (online) [Sat. 25 Jun 2022 18.00 BST]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jun/25/taymour-soomro-i-want-to-challenge-reductionist-narratives-about-pakistan

[4] William Shakespeare Hamlet (Act 1, Sc.5 lines.103ff. Available at: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/Hamlet/entire-play/

[5] Taymour Soomro (2022: 238) Other Names for Love London, Harvill Secker.

[6] Mark Solms in the University of Cape Town Futurelearn course on his research. For my blogs on this follow this link to his relevant book and this for more thoughts on confabulation.

[7] Soomro op.cit: 235

[8] Ibid: 3

[9] Ibid: 69-71.

[10] Ibid: 40

[11] Ibid: 91

[12] Ibid: 33

[13] Ibid: 42f.

[14] Ibid: 5

[15] Ibid: 54

[16] Ibid: 22

[17] Ibid: (for example & respectively) 26, 69 & 213.

[18] Ibid: 85f.

[19] Ibid: 190

[20] Ibid: 35ff.

[21] Ibid: 49

[22] Ibid: 52

[23] Alex Preston, op.cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Soomro op.cit.: 205f.

[26] Ibid: 135f.

[27] Ibid: 18

[28] Ibid: 44

[29] Ibid: 94