Are either or both a gay Lorca and a queer Lorca what Alan Contreras might mean by ‘Unreachable Lorca’ in his review [in Gay and Lesbian Review] of a new book on Lorca?[1] This blog examines the troubling and resistible voice in Lorca’s monologue about what makes the love of men by male poets acceptable in his Oda a Walt Whitman [Ode to Walt Whitman]? Along the way, Steven, the queer-identified blogger, queries his own ‘dark (or obscure) love’ for Lorca and why he still needs to understand what ‘amor oscuro’ means to him, even if it is not necessarily the same as what it meant to Lorca. This blog reflects on Valis’ readings of the poet in a queer light (with reference to Noël Valis (2022) Lorca After Life New Haven & London, Yale University Press).

Noël Valis (2022) Lorca After Life New Haven & London, Yale University Press and Lorca touring at Huerta de San Vicente with his popular Theatre company La Barraca in 1932

Alan Contreras in reviewing Noël Valis’ (2022) book about Lorca states, just to make the obvious point given the fact that the poet was murdered by Falangist Fascists in 1936, that ‘Lorca was not a modern gay man, yet he is a shining part of our cherished history’. Whilst the idea of a ‘modern gay man’ eludes me, I fully agree that Lorca is an important model for multi-authored emergence of multiple modern public queer identities and, in that sense, more than a ‘shining star’. Nevertheless, Contreras agrees with Valis in seeing the poet as ‘a man never quite clearly seen or firmly grasped’, as someone whose ‘unreachability’ derives in part from perceptions that “an air of incompleteness characterizes the man and his work”, according to Valis’.[2] In my own attempt to look at Lorca as clearly as I can wonder if attempting to see Lorca, or any pre-modern (in our perspective) figure in art, in the light of an incomplete gay person is helpful or respectful of the shared humanity of the many expressions of sex/gender and sexuality that a genuine liberatory perspective with regard to our expressions of love, attraction and mutual pleasure would promote.

Queer is a term that may be a better alternative, even given the offensiveness it conveys to many people with experience of it as a homophobic insult. This is because ‘queer’ covers any expression that in some way eludes norms and does not intend to establish its own as is the case with heteronormative and homonormative descriptive language. But we ought to quickly note here that Lorca himself would probably, at least in the public sphere, have hated the English term ‘queer’, even if he had it translated. For this blog, rather than reviewing Valis’ book instead wants to explore what we learn from it about how to read queer poetry wherein positive expressions of queer love experienced in private can co-exist in Lorca’s Ode To Walt Whitman with, what Contreras calls a ‘strange rant against public expressions of homosexuality’ or ‘los maricas’, a Spanish term that is the implicitly but variedly translated to mean ‘queer’ by Valis but is also variously translated by others as ‘pansies’, ‘faggots’. Valis makes special use of referring to what Lorca means by ‘los maricas’ as the ‘crowd of gays’.[3] We will return later to why Valis uses the invented English idiom ‘crowd of gays’ here when considering his new reading of what Lorca does in this poem; a reading not accounted for by Contreras’ characterisation of the poem’s ‘strange rant’.

My own feeling is that Lorca needs something more inclusive than los maricas to celebrate in the meaning of Whitman as a queer poet, including both (translations are in the footnotes);

… el muchacho que se visite de novia

En la oscuridad del ropero,

and:

… los hombres de mirada verde

Que aman al hombre y queman sus labios en silencio.[4]

The terms of Lorca’s passion for boys and men who love men lie in the alliterative and assonantal sibilants of the Spanish ‘sus labios en silencio’ (‘their lips in silence’ doesn’t carry this beauteous if oppressive weight). It lies too in the ‘o’ vowels of ‘oscuridad del roperos’ (absent in ‘darkness of the wardrobe’). There is a silencing, as well as obscuring, of the sexual thrill conveyed by Lorca, a poet who has mastered sound effects in poetry, in those o’s and s’s which interactively becomes part of that sexual thrill as Lorca’s love of love and bodies interacting with secret psychosocial roles mounts. Contreras (for The Gay and Lesbian Review remember) sees these lines as Lorca breaking his ‘reticence’ on ‘the topic’ of gay love, despite the ‘strange rant against public expressions of homosexuality’ also in Ode to Walt Whitman and the fact (as he sees it) that ‘he was not officially out during his lifetime, and very little of his written work has anything resembling a gay theme’.[5] The word ‘officially’ in this quotation rings oddly. What is it to be ‘out officially’? My pondering of this question, where ‘officially’ means, presumably, at ‘a public level authorised by someone’ leads to me concluding that we will never understand our history without confronting the fact that same-sex/gender love has always had a kind of liminal expression on the edges of what is publicly validated and has had few boundaries in that time (even before the invention of homosexuality as a psycho-medical category). For instance, try these frank and funny lines from Christopher Marlowe’s Hero and Leander , first published in 1598, wherein an old, wise and wily Neptune plays with the body of ‘Amorous Leander, beautiful and young’ thinking him at first to be Ganymede, Jove’s lover and cup-bearer.

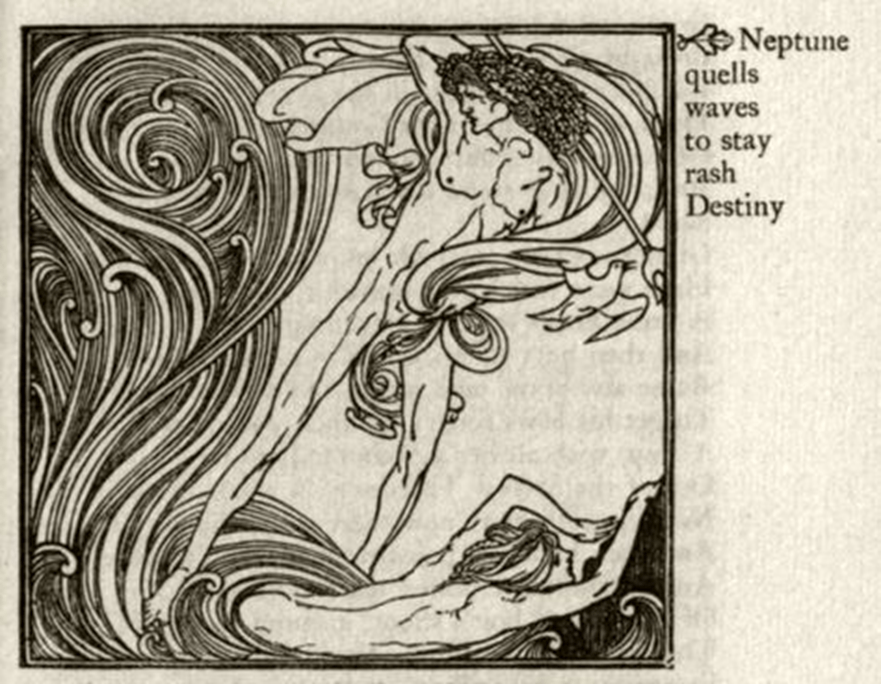

Charles Rickets, a gay artist, pictures Neptune and Leander at sea. Available: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/133137732721948571/

The lusty god embraced him, called him “Love,”

And swore he never should return to Jove.

But when he knew it was not Ganymede,

For under water he was almost dead,

He heaved him up and, looking on his face,

Beat down the bold waves with his triple mace,

Which mounted up, intending to have kissed him,

And fell in drops like tears because they missed him.

Leander, being up, began to swim

And, looking back, saw Neptune follow him,

Whereat aghast, the poor soul ‘gan to cry

“O, let me visit Hero ere I die!”

The god put Helle’s bracelet on his arm,

And swore the sea should never do him harm.

He clapped his plump cheeks, with his tresses played

And, smiling wantonly, his love bewrayed.

He watched his arms and, as they opened wide

At every stroke, betwixt them would he slide

And steal a kiss, and then run out and dance,

And, as he turned, cast many a lustful glance,

And threw him gaudy toys to please his eye,

And dive into the water, and there pry

Upon his breast, his thighs, and every limb,

And up again, and close beside him swim,

And talk of love. Leander made reply,

“You are deceived; I am no woman, I.”

Thereat smiled Neptune, …[6]

Openness about sexual pleasure between males is very much the secret of the Gods (Gods whom he believed to be a fiction) to Marlowe in this poem, and hence the more delicious, caught in the humour of the piece based entirely upon mortal limitation to the concept of heteronormativity: “You are deceived, I am no woman, I,” says Leander naïvely, a line at which Gods and the those in the know about this secret pleasure ‘smiled’. It’s a beautiful and wicked piece, based on the sly smile which cultivated and sophisticated readers share with Neptune and the play of amorous loving glances, words and sensual touch. Something like this survived in ‘our cherished history’ as queer folk, to emerge linked to a sense of shame and sin absent from Marlowe and ‘The School of Night’ (as modernity knows Elizabethan free thinkers) to which he was, allegedly, attached. Even as a young man when I was awfully earnest about clarifying the central importance of having an open and public gay identity in the 1970s, there were older men who looked back at the covert nature of the pleasures they were compelled to limit themselves to as part of the ‘fun’ of the fulfilment of queer physical desire. I was appalled but, looking back I was also naïve and somewhat arrogant, a view which now sustains groups like the LGB Alliance, which construct sexual politics into a system of hate to match the old hate once shared by LGBTQI+ people indiscriminately.

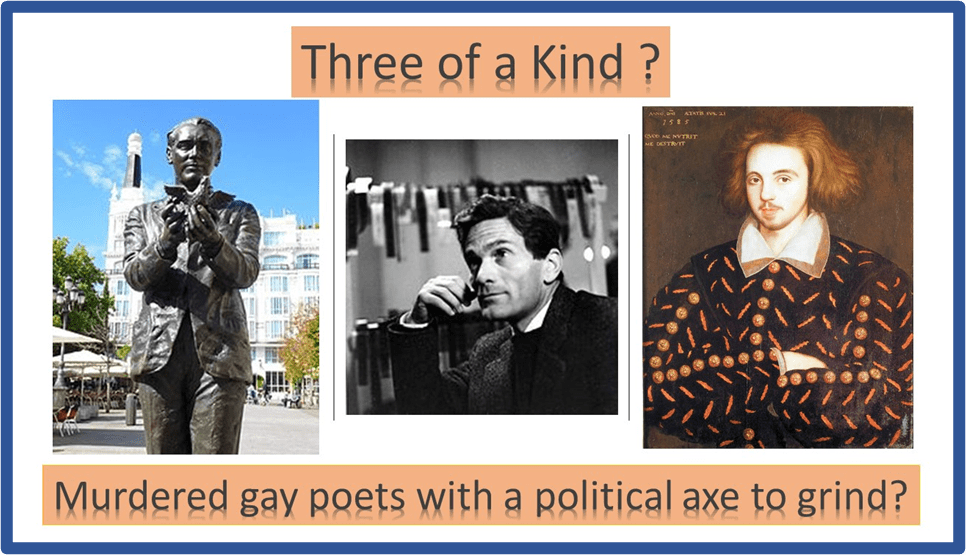

I find myself liberated to speak of Marlow next to Lorca as part of a queer ‘dead poet’s society’ for so does Valis in discussing the deaths of queer artists whom he compares to Lorca, including Pier Paolo Pasolini, who have been murdered and whose death has been linked, possibly apocryphally, to the combination of their sexuality and public political stance and whose lives shed, in Valis’ words, ‘an oblique, if precarious, light’ on each other’s lives:

The same uncertainty about their lives (and deaths) extends into the intricate loops and folds of the psyche, suggesting how pointless it is to assume we know anything of Lorca’s inner life or his sexual complexity.[7]

Hence, I am not aiming either to claim to know about whether Lorca himself constructed the idea of being a queer man in any way we can know for certain. However, the words of his Ode to Walt Whitman do seem to spring from common themes about what it might mean to a person to be queer, in the light of other social models of that behaviour and/or identity. This is the approach to Lorca I’d like to follow. The lyric ‘I-voice’ of the poem in question defends secret longing with a trans edge to it whilst distaste for what is overly public. In New York the ‘I-voice’ confronts a group belief in the principle of a male gay commonality defined by the phallus (‘de carne tumefacta’), which could be contrasted with ‘viejo hermoso’ (lovely old man’) Whitman’s generosity to and for all people, however despised some of these were by convention.

It is in this context, the vileness of the rant seems to be about the way that public expressions of homosexuality become only expressions of an identity looking for relationships only viscerally (meatily – ‘de carne tumefacta’) sexual and robbed of the private expressions of a more integrative love between not only men but also between conjoined bodies, and emotional and/or spiritually defined lives. See these moments in the poem (again translations in footnotes):

Porque por les azoteas,

agrupados en los barres,

saliendo en racimos de las alcantarillas,

temblando entre las piernas de los chauffeurs

o girando en las platformas del ajenjo,

OR, perhaps, here, where the ‘I-voice’ of the poem raises his voice;

… contra vosostros, maricas de las ciudadades,

de carne tumefacta y pensiamento inmundo.

Madres de lodo. Arpías. Enemigos sin sueño

Del Amor que repartee coronas de alegria.[9]

The main strain of Valis’ re-interpretation of Ode to Walt Whitman relates to the identity of the ‘I-voice’ in the lyric which Valis does not confound with that of Lorca or his autobiography. This is an unusual step, given other readings. We can start with Ian Gibson, Lorca’s exhaustive and comprehensive biographer; whom, according to Valis, was the main force of publicising the poet’s erstwhile neglected statements of his sexuality.[10] Gibson describes the poem as a transitional one in terms of Lorca’s ‘coming out’ process: saying it ‘suggests that, despite his efforts, Lorca had not yet come to terms with his sexuality’. This, he suggests, is the source of Frederico adopting an ‘I-voice’ which is a ‘diatribe’:

… directed not against homosexuals as such, but against the effeminate variety and those who ‘corrupt’ others, all of it from the point of view of a hypothetically ‘pure’ homosexuality free of blemish.[11]

Yes, but, any person coming out ‘gay’, as I was in the 1970s, would say that most homophobes they experienced (and there were many in the institutions of politics, education, the arts, and work) claimed that the only stood against those who corrupted young people. Indeed, there is solid historical evidence for this now, which I find best described – calmly and objectively which I sometimes struggle to imitate in a subject which touches on my fashioning as a person – by Chris Waters in his 2013 essay, ‘The Homosexual as a social being in Britain, 1945-1968’.[12] In effect I can understand then Gibson being encouraged to see Lorca’s poem as a personal statement as a profound personal ambivalence about men loving men that belongs to an underdeveloped process of identification with that role and persona, given the negativity of the social imagery that was hegemonic in constructing what was meant by meant by ‘homosexuality’ in the period. However, such views have not gone away. Joanne Cherry and J.K. Rowling can reproduce them in the debate about trans people in Scotland for instance, almost exactly in the terms of Lorca’s ‘I-voice’.

This is the context in which I find Valis’ comprehensive and many-faceted socio-cultural re-reading of the Ode to Walt Whitman useful. In doing so she invokes later queer poets, such as Luis Cernuda and Luis Muñoz.

She cites these poets thus:

Cernuda, who was also gay, likened [the Ode to Walt Whitman] likened the work to an unfinished sculpture “because the block of marble contained a flaw.” Much more recently, another gay poet, Luis Muñoz, begged to differ, seeing in the inconsistency of the “Ode” an invigorating openness and vulnerability, and this, despite fighting with the poem “every time [he] reads it.” … Muñoz found in Lorca not only a poetic exemplar but a personal one, precisely for the inner battles the poet endured in order “to speak out from a homosexual standpoint”.[13]

As I read this with gratitude (especially regarding how gay poets have themselves struggled in valuing this poem), I still want to differentiate it, as Valis goes on to do in effect but in the whole range of his complexly structured book, from being a ‘personal statement’ by a queer man Lorca about himself. Of course, I am aware that this is not entirely possible, for in the lyric – fused as Lorca’s lyrics were with narrative and the feel of being dramatic monologue – the ‘I-voice’ is both and another persona’s voice. The persona’s voice is one that links at a deeper level with the poet’s own complex personae, for these are always multiple. We can’t even read Lorca’s dramas (Yerma for instance) without that being clear.

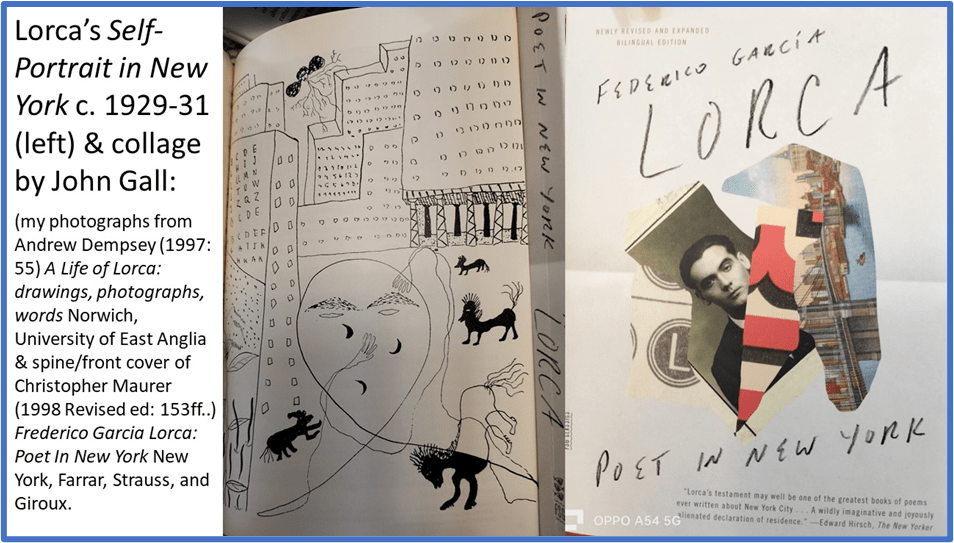

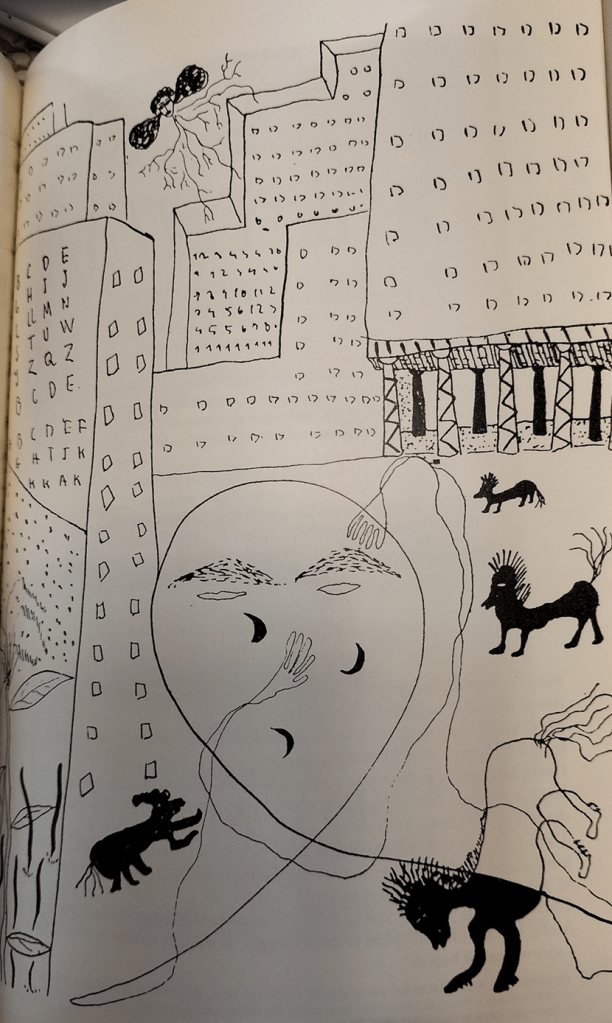

A clue to the multiplicity of selves in Lorca might be found in his drawing Autorretrato en Nueva York (Self-Portrait in New York) since this homage to his favourite artist, Joan Miró, works as a self-portrait only at a level of psychoanalytic fragmentation of what we mean by self.

Valis examines this picture in terms of its liminal difficulties. It is, as it were, impossible to draw clear boundaries to the self apparently contained (or not contained) by it. There is a central figure, but it consists only of feature that might represent other things, such as crescent moons, hills and lakes, natural forms in abstraction that contrast with the zoomorphs that variously inhabit the landscape around the figure but also intrude into it into parts, for the delineated body is only partially connected to the ‘pearlike balloon face’. These semi-natural forms are drawn such that their faction is paramount (one horse is coloured in only in the part of its body that lies within the line denoting the central figure’s body). They contrast with icons of the urban, monumental shapes that could be skyscrapers or tenements. Pointedly modernist, some building boast column holding them into the air such as was the trademark of Le Corbusier. These ‘homes’ are no doubt ‘machines to live in’. One ‘skyscraper’ bears on its frontage not windows but the calligraphy of an alphabet to mark the intrusive mechanism of the human artefact into life, beneath which yet more marshy unruly nature appears to want to grow. I think we need a larger version of the drawing to check these details.

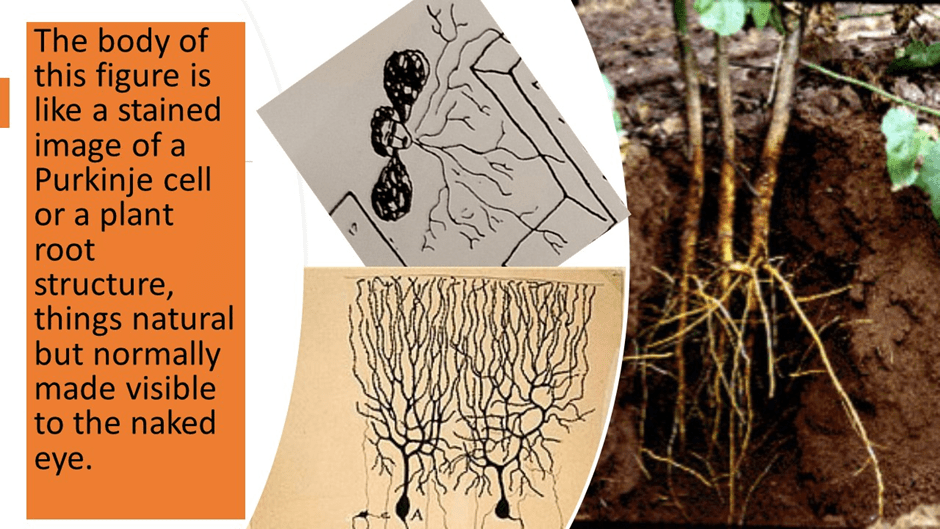

A second figure appears as if standing on a penthouse roof behind the close-up central figure, whose head is like a seed with a face, but with appendages to each side which could be hair or could be speak bubbles. The body of this figure is like a stained image of a Purkinje cell or a plant root structure, things natural but normally made visible to the naked eye.

Lorca’s images are not simple or easy to read but Valis is surely on the right track in seeing the elements of the scene as referring either to ‘external urban threats … or to obscurely felt internal projections or both’, also serving to tell us ‘how thin the veneer of modernity s, how deep myth’.[14] I fully agree that they suggest that Lorca was insisting on the fragmentation of self into personae and that this can be read into the Ode to Walt Whitman as a poem that dramatises such conflicts, wherein the ‘I-voice’ is just one voice amongst many, possibly in the same person. What Valis also points out that the venom of the ‘I-voice’ against those identifying with what he calls ‘los maricas’ are hated for they point out that Whitman is in fact ‘one, too!’ (one of ‘them’):

los maricas, Walt Whitman, te señalan.

ịTambién ese! ịTambién! [15]

No wonder the ‘I-voice’ must ‘raise its voice’ for these that are pointed out and scorned can turn on and claim Whitman to be as themselves, and if they can do this cannot they do it to to the ‘i-voice’ too. Hence he must shout out the most appalling modern myths of the danger of the out community of gay men in all their international and Iberian Peninsula names (Fairies, Pájaros, Jotos, Sarasas, Apios, Cancos, Floras and Adelaidas).[16] And what he shouts out is condemnatory: that they ‘give boys / drops of foul death’, so impure that they ‘emerge from sewers’. And this is hard to read but only because it lies in the traumatic experience of most queer men, where sometimes these voices get introjected in a frenzy of self-hate as if they were your own. If this is so, we should laud this poem as the greatest if most resistible queer poem ever.

This is the more important in that we should not divorce such a reading of the fragmented split nature of its personae in speaking of queer experience from other biographical possibilities. For instance Stephen Spender and J. L. Gili speculated in 1943 that Lorca’s ‘friendship with Salvador Dalí may well have some bearing on these poems’, for we may still think that the venom in that relationship as it ended rancorously may well have contained its elements of combined hate and love.[17] But this does not influence the fact that the poem’s power is dependent on ambivalence. Valis thinks it relates to Lorca’s ambivalence about the power of crowds, politically, socially and economically in the modern World, in the Spanish Civil War frenzies and in the commercial variant of American capitalism in New York (his chapter is called ‘A Face in the Crowd’).

This feels plausible too and it makes sense in terms of the poem’s anguished separation of queer love in the trembling silence of all kinds of private closets and the public places in which los maricas gather. Did Lorca fear and desire a ‘community of gays’? We will never know. However, as Valis points out that although the ‘los maricas’ land on Whitman’s ‘barba luminosa y casta’ (luminous and chaste beard) fouling it, they may for reason be difficult to distinguish in the poem from what also beautifies the man and his beard earlier: ‘tu barba llena de mariposas’ (your beard full of butterflies), for the term’ los mariposas’ is not only assonant with ‘los maricas’ but both could be used to refer to queer men in Spain.[18]

For me this is the value of Valis’ book, although it also takes me back to the fact that Lorca thought and felt long and hard about the problem of sexual desire and its ambivalences. In The Public (what fragments we have of it) , it allowed him to see that what is considered dirty and foul (indeed scatological) can in the moment of desire, involving transformations of self be beautiful, explain the bit of it that puzzled Ian Gibson and revolted others. When I saw this scene enacted in Edinburgh I found it enthralling and beautiful, if queerly:

… the series of metamorphoses enunciated by the lovers in the scene entitled ‘Roman Ruin’, … (‘if I changed myself into a turd? ‘I would change myself into a fly’, etc.).[19]

And perhaps more than others I think Lorca felt it important that the growth of a public community of queer people did not lose the qualities of what he call ‘dark love’ in his Sonetos del amor obscura. These glorify a kind of secret passion built of sado-masochism that he makes beautiful (‘boca rota de amor y alma mordida’)l, even if I am resistant to finding them so (it takes all sorts).[20] He finds this too in the shady allies of orientalist poetry that speaks of lost traditions of Granada – the world of a poetry nearly Persian, such as in one poem ‘Of the love that hides itself’, surely recalling Wilde, but celebrating love beyond conventional norms:

me abrasaba en tu corpo

sin saber de quién era.

(I burned in your body

not knowing whose it was.)[21]

Of course I can’t leave Valis’ book without pointing out that much of it is not about Lorca as a gay or queer man. For her, the myth of his death allows his appearance in many mythic structures appealing to many communities. In this the idea is not so new. It relates to the idea of the poet creating a monument to his poetic voice that is universal because multi-voiced but, though all of it is interesting and brilliantly researched, I can’t help finding the sections on the fascist right wing’s claim to Lorca as one of their own disturbing and a little unnecessary. Some things in history dearly deserve to be forgotten forever.

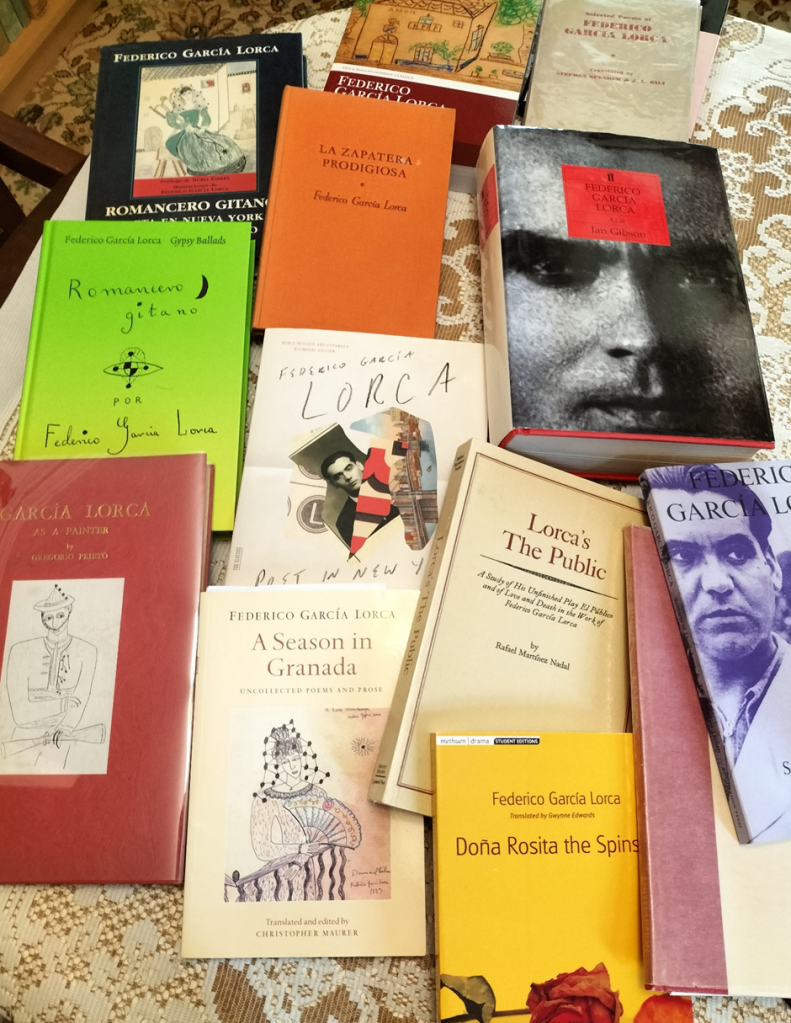

My Lorca books displayed on the table to use in this blog.

All the best

Steve

[1] Alan Contreras (2023: 39) ‘Unreachable Lorca’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review XXX (1) Jan.-Feb. 2023, page 39.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The term ‘pansies’ is used to translate it by Stephen Spender & J.L. Gili (1943: 34ff) Selected Poems of Frederico Garcia Lorca London, The Hogarth Press, ‘faggots’ by Greg Simon & Steven F. White inEd. Christopher Maurer (1998 Revised ed: 153ff..) Frederico Garcia Lorca: Poet In New York New York, Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux and) or ‘crowd of gays’ (Valis op.cit: 268).

[4] Maurer op.cit: 158. Translated 159: ‘… the boy who dresses as a bride / in the darkness of the wardrobe’ and ‘the men with that green look in their eyes / who love other men and burn their lips in silence’. Valis op. cit: 269 translates ‘del ropero’ as ‘of the closet’, perhaps with an eye to queer theory and context.

[5] Alan Contreras, op.cit.

[6] Christopher Marlowe (1598) Hero and Leander available in full text at: https://archive.org/stream/heroandleander18781gut/18781.txt

[7] Valis op.cit: 174

[8] Ode to Walt Whitman Maurer, op.cit: 154. Translated 155: ‘because on penthouse roofs, / gathered at bars, / emerging in bunches from the sewers, / trembling between the legs of chauffeurs, / or spinning on the platforms of absinthe, the faggots, walt Whitman, point you out’.

[9] Ode to Walt Whitman Maurer, op.cit: 158. Translated 159: ‘against you, urban faggots, / tumescent flesh and unclean thoughts. / Mothers of mud. Harpies. Sleepless enemies / of the love that bestows crowns of joy’.

[10] Valis, op.cit: 159

[11] Ian Gibson (1989 thus: 298 [with both volumes in one]) Frederico García Lorca: A Life London, Faber & Faber.

[12] Chris Waters (2013) ‘The homosexual as a social being in Britain, 1945-1968’. In Brian Lewis (Ed.) British Queer History: New Approaches and Perspectives Manchester & New York, Manchester University Press, 188-218

[13] Valis, op.cit:273f.

[14] Ibid: 272

[15] ibid: 154. Translated 155: ‘the faggots, walt Whitman, point you out / He’s one, too! That’s right!’.

[16] Ibid: 156f.

[17] Spender & Gili op.cit: 7

[18] Maurer op.cit: 154f.

[19] Ian Gibson op.cit: 297

[20] Frederico Garcia Lorca (trans J. Damon & G. Garcia Lorca) Ghazal IV ‘(2017: 98f.) Sonnets of Dark Love / The Tamarit Divan London, The Enitharmon Press. Translates thus: ’mouth broken by and soul bitten’.

[21] ibid: 54f.

2 thoughts on “Are either or both a gay Lorca and a queer Lorca what Alan Contreras might mean by ‘Unreachable Lorca’ in his review [in ‘Gay and Lesbian Review’] of a new book on Lorca? This blog examines the troubling and resistible voice in Lorca’s monologue about what makes the love of men by male poets acceptable in his ‘Oda a Walt Whitman’ [‘Ode to Walt Whitman’]? Along the way, Steven, the queer-identified blogger, queries his own ‘dark (or obscure) love’ for Lorca and why he still needs to understand what ‘amor oscuro’ means to him, even if it is not necessarily the same as what it meant to Lorca. This blog reflects on Valis’ readings of the poet in a queer light (with reference to Noël Valis (2022) ‘Lorca After Life’.”