A blog on my second lecture to a Human Growth and Development Course in Social Work (Sample Lecture 2). Attachment Theory & understanding how humans develop & grow relationships over the lifespan: Perspectives on Human Growth and Development for Social Workers. [Social workers and their interactions with complex relationships in families and other psychosocial networks. How to work in & with relationships].

The second lecture of this course in preparation develops further ideas about how social workers open themselves up to hearing and understanding, rather than just using, the voices of people of lived experience. It cannot yet deal with how social workers prepare themselves to talk and think about their own beliefs about personal growth and the development of their mature wellbeing, although this is implied in the Daniel Taggart piece I refer to later for follow up learning. In developing relationships, humans often feel that they draw down into experience memories of what to them constitutes their own particular past life. Such memories get used in interpreting and shaping the present and relationships in it as they work on that bit of their present life defined by that relationship, in the light of a future they would like to see. Not all of that process is conscious and needs to be if the social worker, as Daniel Taggart insists, is to avoid countertransference reactions. But we need our lecture on psychodynamics before we can touch on this,

Relationships occur at all levels, and none are insignificant, even those which constitute ‘people work’. I believe that social workers need to see themselves as developing and growing a relationship with people with lived experience of services in most of what they do, which often involves addressing not only their direct relationships with significant others of the person (family, carers, and lovers) but those necessitated for them by using social work either voluntarily or involuntarily.

The lecture proper falls into two parts described in the following agenda slide. First by leading learners to an awareness of how they confront ‘real’ life stories and how they understand them, including their role as shaping them. Some of these stories are indeed the work, or part of it, that is done in social work to:

- Engage both participants in that relationship in the work to be planned and delivered, including any necessary assessments.

- Build motivation and context related to the changes that social work brings about.

- Evaluate the work.

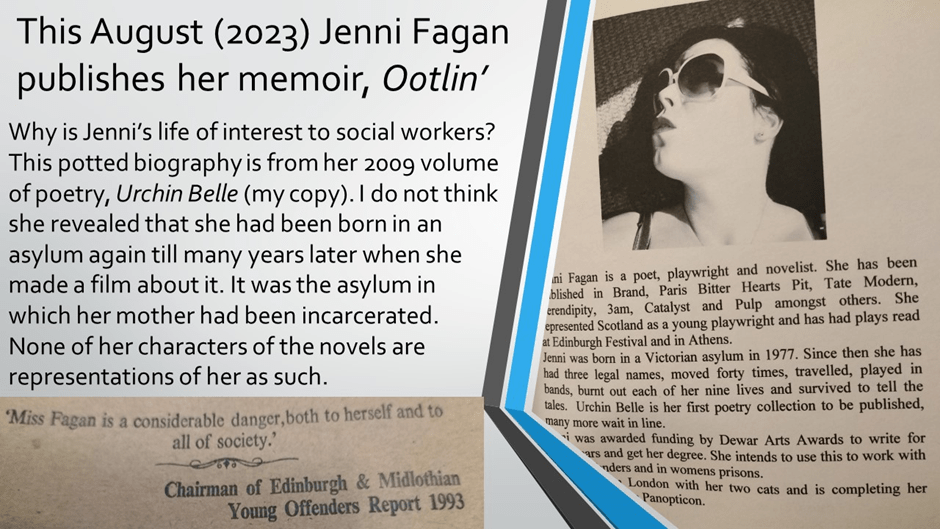

However, using a person’s story may in some ways bias the representation of what the experience being lived means to the person enjoying or enduring work on, in and telling their lives with a social worker or other practitioner. This is a much bigger topic than can be dealt with here. However, I introduce the issue by looking at the work of Jenni Fagan, novelist, playwright, poet, artist and soon to be memoirist. Her work often touches on the lived experience of fictional characters but is fired by the dynamic of her own reflection of being a person of lived experience of services in several domains.

We will think about how relationships form part of the things requiring social work, in family organisation and functioning for instance, in couples work, including domestic difficulties and violence (even where the work aims to separation in a relationship as a potential way forward). We will think about it in groups and then feedback. Then we should check against this list. At this point I will say the persons of lived experience we will mainly deal with today are very young people in families of all types, the experience of care and care-leaving.

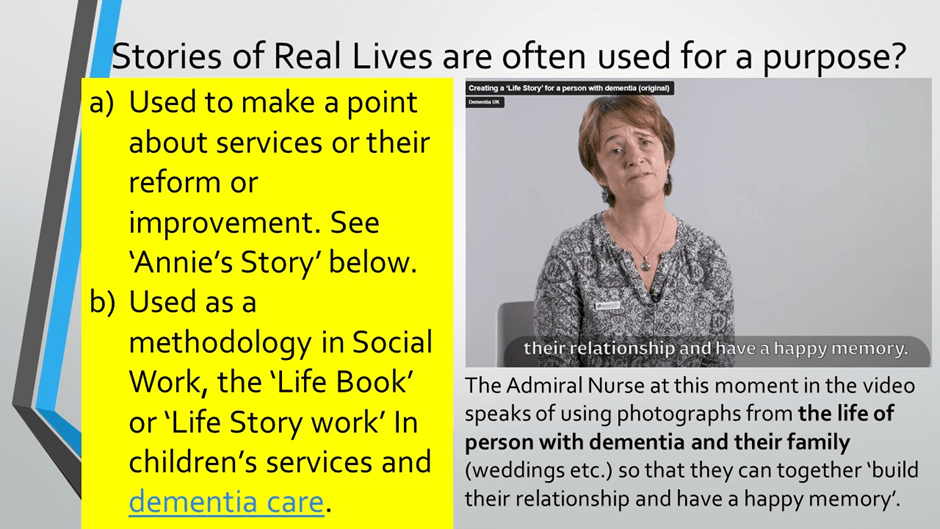

We start with real life-stories evoked in social work and allied professions in ‘people work’. My main concern is children and families work this week, but it helps to start with a different arena, so that we keep our selectivity amongst topics in mind. My aim in all though is to show that, by being used as part of a social work agenda, these stories can sometimes take distorted forms in relation to the realities of the lived relationship. My own suspicions about the agenda of ‘enforced cheerfulness’ in people work is heavily apparent in the Admiral Nurse who speaks in the video (link to video) referred to in the next slide (Admiral Nurses are nurses working with people with a dementia and their carers and supporters) where the content of the work is to create ‘happy memories’. I will assert the double-edged nature of such a goal for people providing care for a spouse, parent, or child and, indeed the person with dementia. For me such ‘therapy’ can, and has in my experience, been harmful whilst certainly serving a purpose for professionals in making appear more marginal the more difficult work that needs to be done in such situations.

The case is less heinous in the next example, but I still think that Annie is using her reflections on her life as a means of promoting an agenda – one in social work education – that is not entirely free from becoming a bias in how she understands her own story (For Annie’s story see link here).

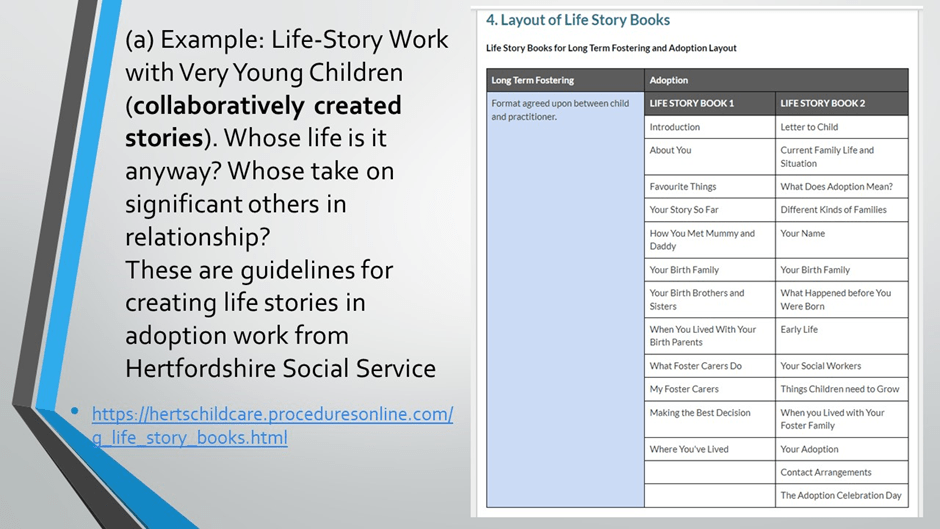

Again life-story work in adoption and fostering is genuinely rooted in the need that define the work (a child is assisted by a means of holding together the story of their identity as they see it) but it is also a tool for the social worker: in some ways this fact may bias the information we think relevant in building a child’s life-story book. As the examples in the following slides show the ‘child’ is at the centre of the story, and process of telling it, but the variations of what this means are huge and depend on very skilled work so that we address issues easily capable of being buried, as so much else might have been in these child’s lives. This is not to say that we enforce a demand that a life story looks at the ‘worst of times’ as well as the ‘best of times’, for as Dickens says these can be simultaneous, but that we do not force the child to further bury material that they find harmful now or might in the future. Of course allowing things to rest until ready to arise and where support is available is part of this skill.

One of the best examples of this can be seen in a brilliant talk by The University of Essex’s Daniel Taggart on attachment work with mothers of at-risk children, where even the social worker must be careful not to collude with suppression of some negatives in close relationships. The piece can be found here: Film 5: Attachment and social work practice – Part three | Research in Practice.

The following slide shows Hertfordshire’s guidance regarding the structuring of life-story books.

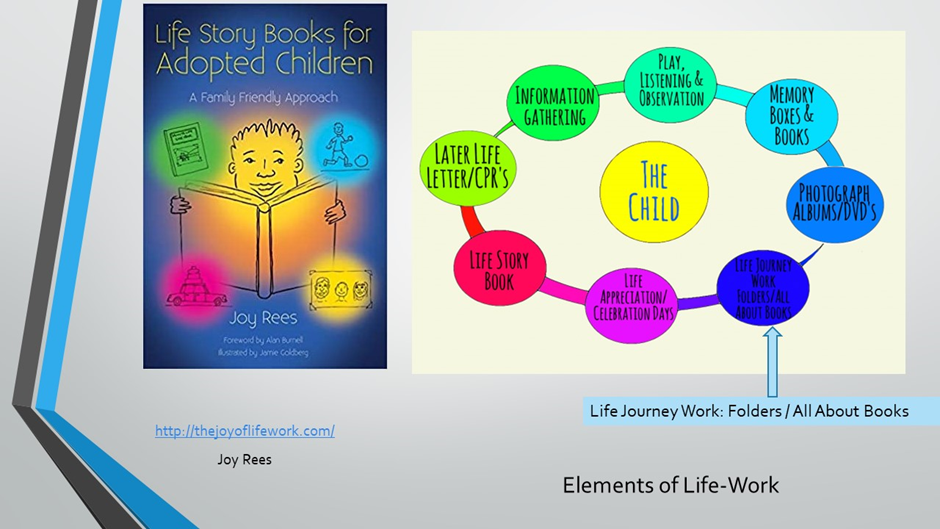

Hertfordshire also recommend the work of Joy Rees to their social workers with regard to life-work. I will open discussion of whether the dominant feel-good nature of the graphics used below reflects all aspects of hearing about these lives from the voices most experienced in them, however fearful and suppressed those voices might currently be. This is something they may take into practice and may have confronted in their recent two-week schools placement.

I will open this argument further here to explain why I intend to look at the lives of fictional people of lived experience, if through the voice of an artist, who is herself a person of lived experience. However, it is important to keep emphasising that this is not because the fictional lives represent the author’s life. Indeed that would be a bad mistake – feeding into the myth that adversity always potentiates success of the type people may think a famous and highly respected literary artist has. Hence the discussion in next slide:

I look first at snippets of biography from one of Jenni Fagan’s earliest books Urchin Belle, in its first rare edition (it was limited to 100 copies, and this is my own).

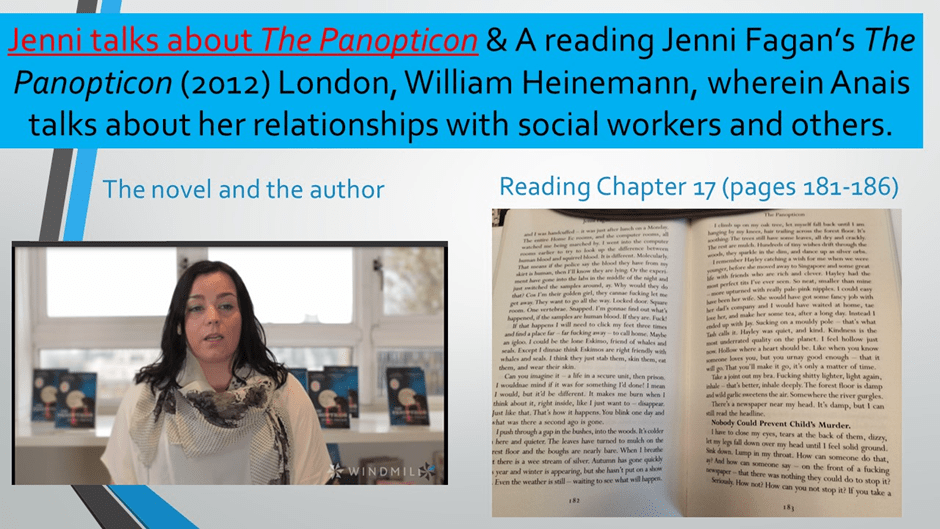

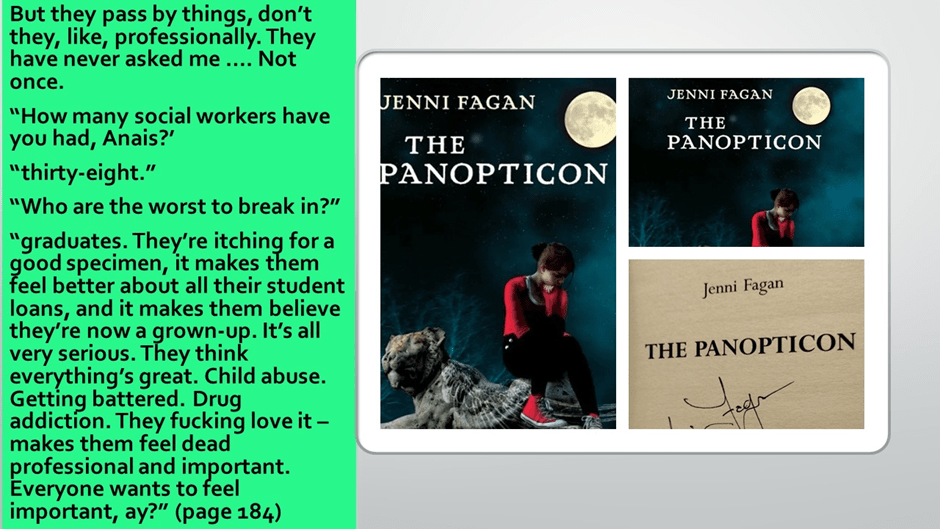

How we approach Jenni. We listen to a video (https://youtu.be/DqawLwbobxY?t=8) in which she speaks about why she chose the care system as the subject of her debut novel The Panopticon, which won many awards and prizes. When this book came out I taught it to social work students at Teesside University – some of whom considered the learning valuable (though there I had to teach it outside the curriculum which was considered not flexible enough for it). Both of the following slides are related to the same point. Chapter 17 will be made available for fuller read-through.

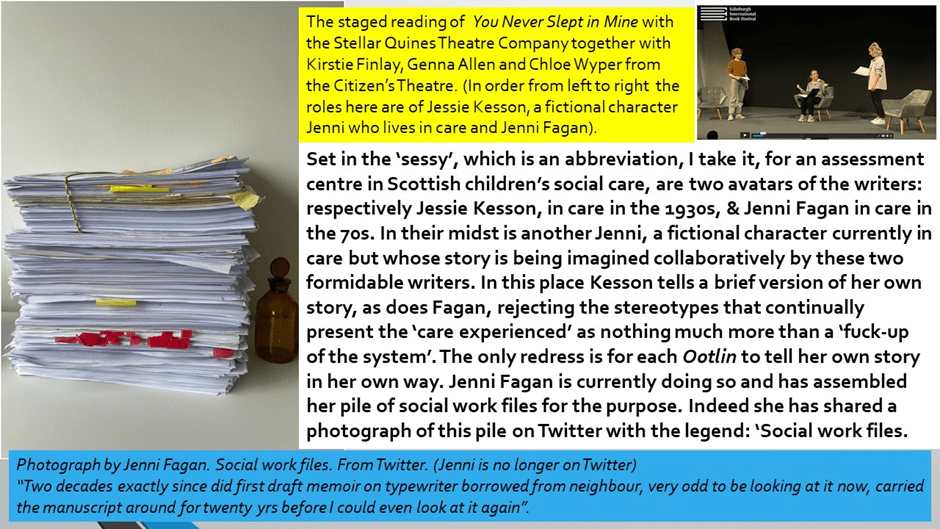

The final slide says goodbye to Jenni by reminding of her memoir about to be published, very largely concerned with the care system, in August this year (mine is already on order) and looking at her visit to a word in its title in a play she wrote based on a radio play by Jessie Kesson, the Ootlin. The slide has food for reflection about how we deal with our own lives as pathways to what we need from our past in order to acknowledge our pain about some of that buried material and to unearth what creates further movement on into greater wellbeing. This is the stuff of social work transformations in narrative-based work anyway and fostering wellbeing is a duty in The Care Act 2014 in the UK.

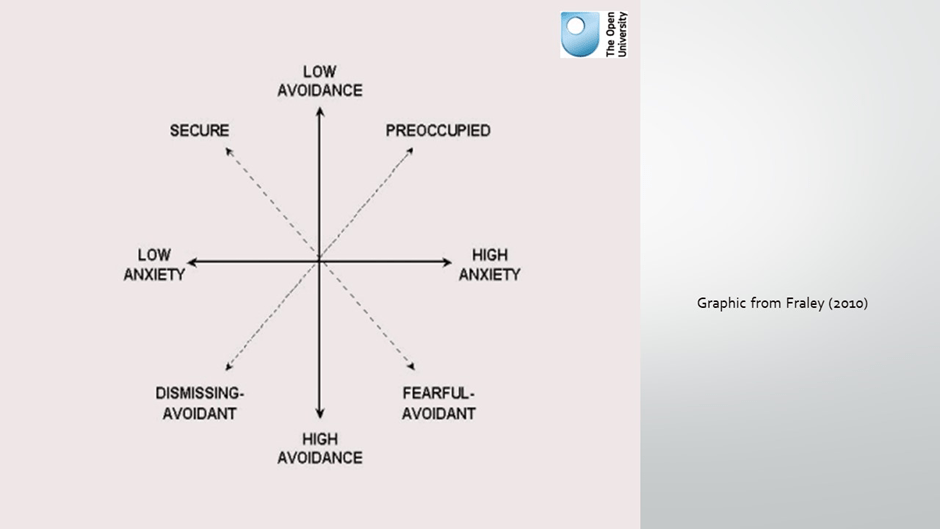

The next two slides takes us straight into the next section of the lecture: How attachment theory might help social workers develop and grow their understanding of (1) the family and other relationships of people with lived experience they work with and on in practice and (2) in understanding how they themselves relate to persons with which they work. Social workers must use and build relationships as part of the development work involved – their own as well as the person using-the-services’ development and growth.

Terminology is important (safe haven, secure base) and we can spend some time thinking about words like security, bonds, closeness & distance.

First, a little context. We can start with the most problematic and lead up to attachment theory. For as Bowlby developed Maternal Deprivation theory, he was not making it as clear as he did later, that the primary caregiver need not be the mother, or even a woman, as long as that person were available and consistent with the child, especially through the ‘critical period’ of early infancy: the maternal deprivation hypothesis. I start with the 4 minute clip from the Robertsons’ A Two Year Old Goes To Hospital (1952) (Link from here to clip).

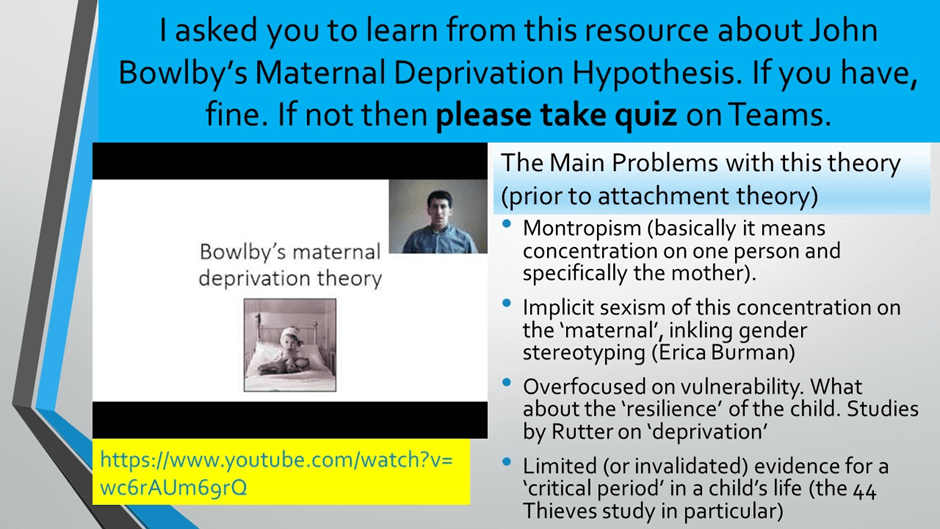

It is my plan to ask learners to watch and make notes on the video on the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis as explained in the video. The video linked here is just over 10 minutes and was designed to help learners in A-level Psychology, It is a good time to look at the classic objections to the implications of attachment theory. Awareness of them is important – more so than the classic defences of what Bowlby really meant. Our aim here is not to be fair to innovative thinkers like he but always be aware of dangers in the possible implicit or hidden messages in simple understandings of psychological and other theory, and foster the critical thinking necessary to the social worker,

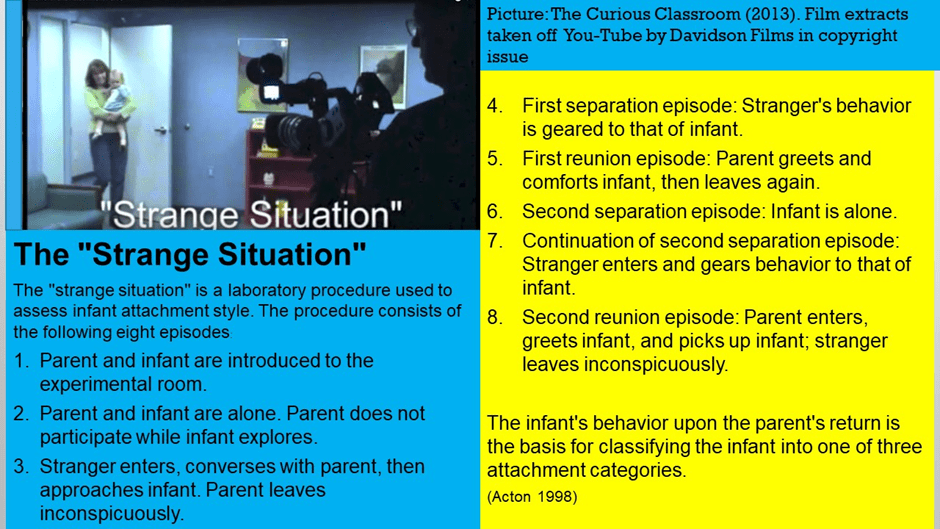

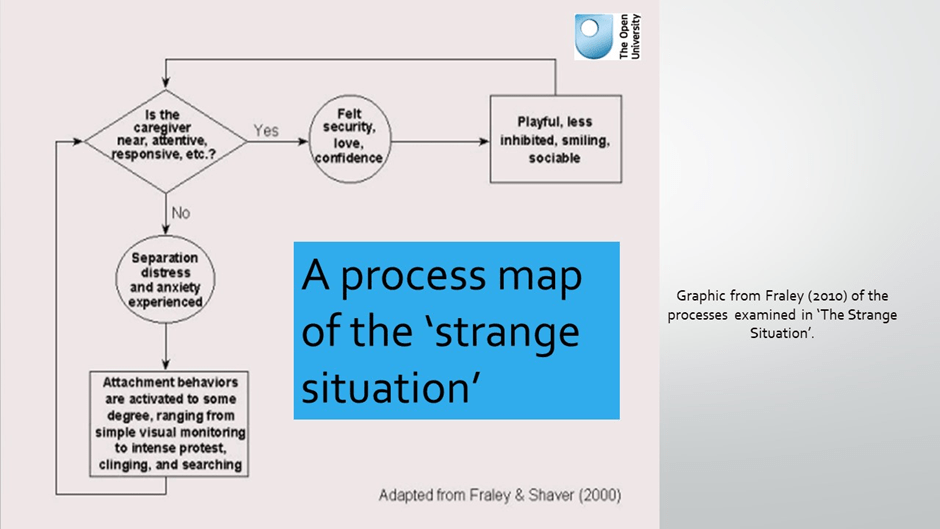

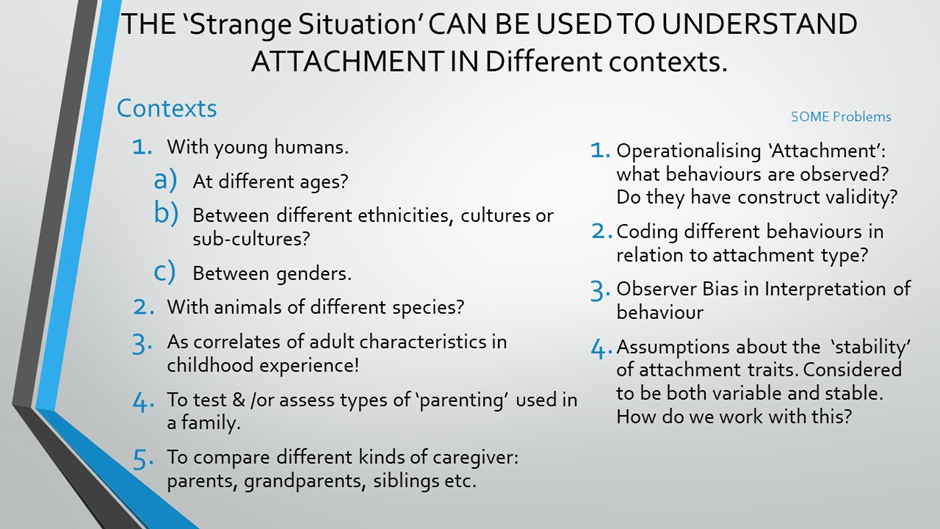

I move on to attachment theory per se via Ainsworth’s ‘Strange Situation’ experiment. The slide below describes the procedure of the experiment. It is followed by a process map of the possible cyclical iterations (repeated sequences of behaviours in the baby experimented upon, which indicate either security or insecurity in the baby about the ‘mother’ as a base for physical, emotional, and cognitive exploration). We can tease the process out and map it against the procedure.

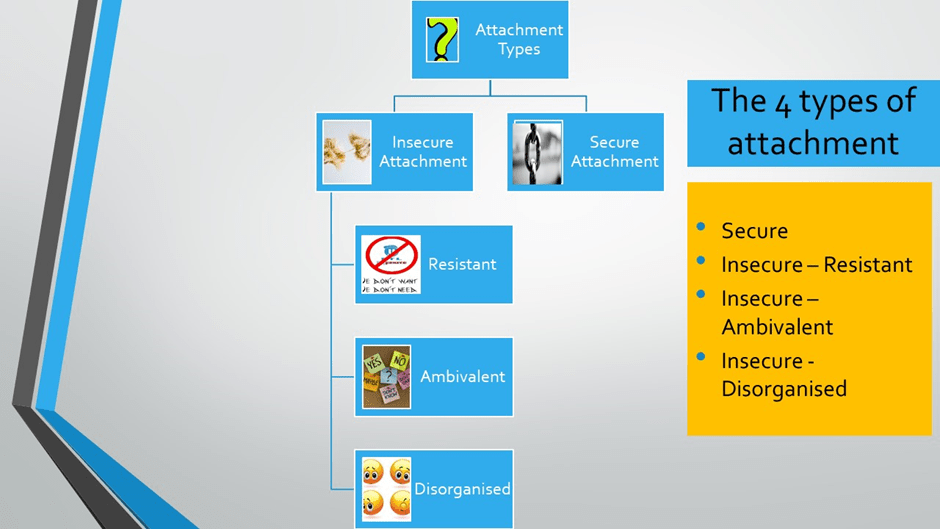

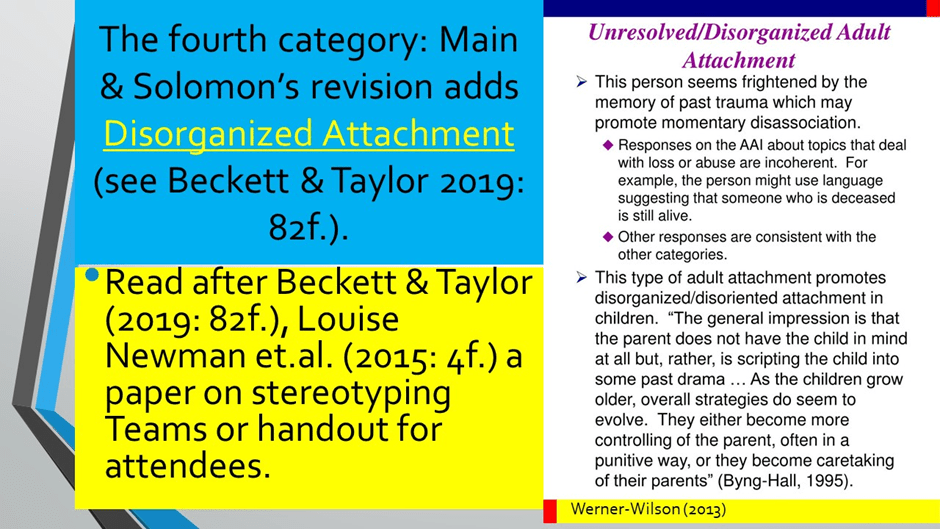

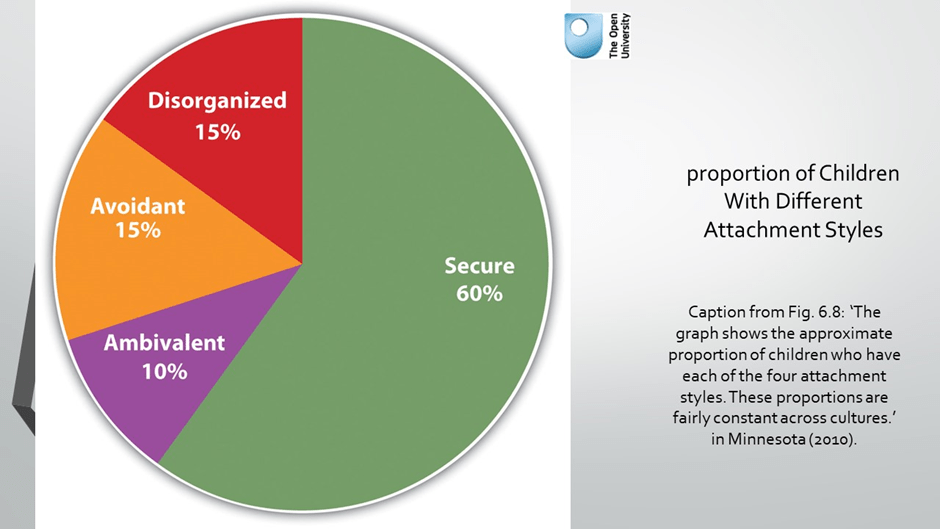

At various points from here I will repeat the names of the different attachment types (and role-play them with learners; for they usually love my exaggerated baby enactments). At this point the Solomons and Main’s 4th category of attachment (Disorganised) is briefly introduced, though it does not appear in later schemas on slides which are based on Ainsworth’s original taxonomy.

We move back a bit to look at how we arrive at Ainsworth’s categories by talking a little about the coding of observed behaviours in this, for this kind of attention to them is well known to people of lived experience who experience such coding in all kinds of assessment by professionals. I will make available the Water’s document on Teams and bring in necessary coding pages for coding CMBs (Contact Maintaining Behaviours). For document see: Waters, E. (2002) Except from ‘Comments on the Strange Situation’. Available from: http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/measures/content/ss_scoring.pdf (Accessed 26/12/2015)

We will try a group exercise, with extended role plays to recreate scenario) in the following two slides and their instructions: Source The Curious Classroom (no longer available on You-Tube).

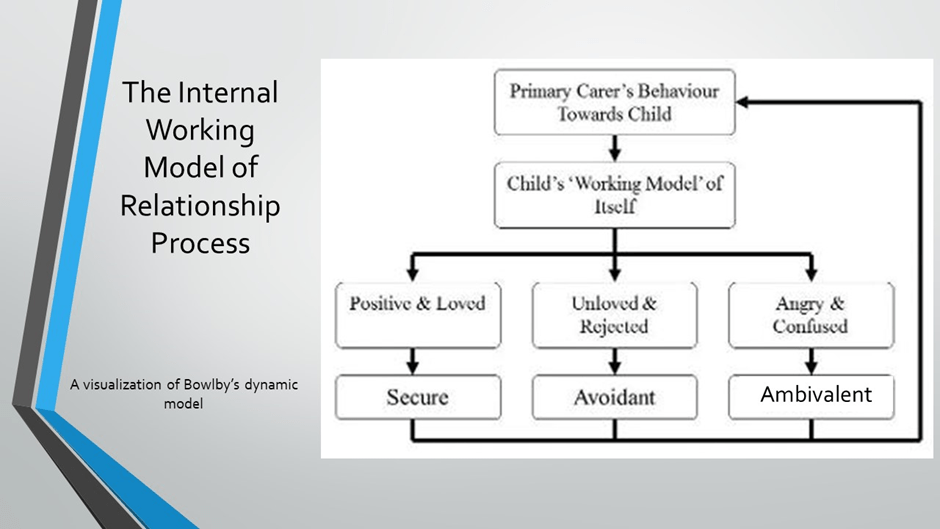

It is important we consider the ‘internal working model’ for it constitutes an introduction to the role of introjected behaviour patterns linked to ideas or cognitions (and helps learners to grasp what is meant by cognitive psychology later in the course). The terms ‘schema’ and ‘script’ are usefully introduced here for placement in terminology dictionaries.

The next is a fun slide on the extension of strange Situation into animal behaviour (some will know Harlow’s infant primate experiments by they raise too much baggage here). It was done for the OU where learners that year were tasked to devise an experiment based on the hypothesis in the slide.

Before we leave the topic, we focus on Disorganised Attachment, for it is of increasing importance in the literature (hence the reference to Louise Newman et.al. – link available on Teams). Reference is Newman L., Sivaratnam, C. & Komiti, A. (2015) ‘Attachment and early brain development – neuroprotective interventions in infant-caregiver therapy’ in Translational Developmental Psychiatry 3 (1), 28647. DOI: 10.3402/tdp.v.3.28647. A further graphic may be explored or followed up (my preference) in source literature in references.

Some suggested prevalence figures and proportions are now given in a pie-chart in the next slide. This will enable reflection in class.

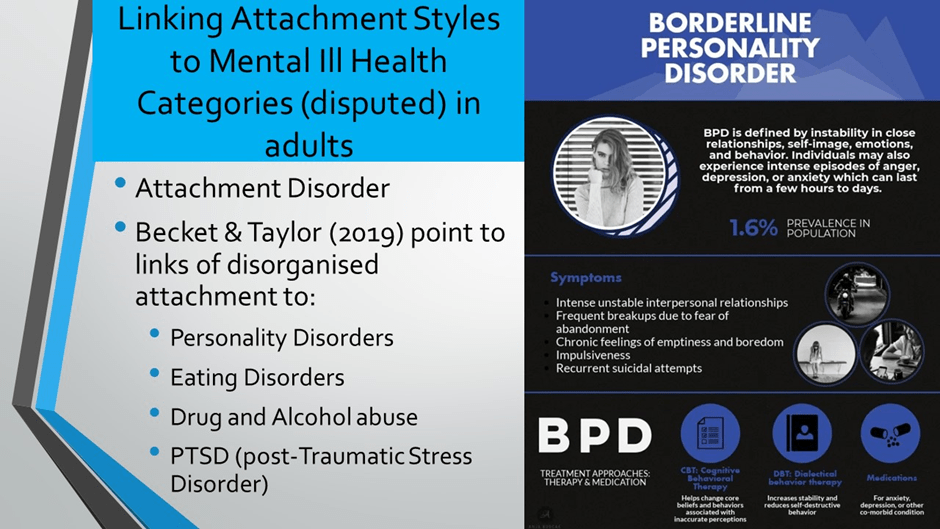

Research & practice contexts are the focus of the next slide, with a brief link to mental health contexts, wherein the concept is not only ubiquitous but used too freely by some to argue some mental health presentations are manifestations of ‘personality’ alone (and not treatable). It has made the term/label Borderline Personality Disorder particularly problematic (I stand with the sceptics on this one – it is a negative term experienced negatively by many of those labelled such – the contemporary case of Zoë Zaremba currently destabilised our own local mental health trust (TEWV) – there was some very bad practice here. I used to correspond with Zoë on Twitter (mainly about her beloved guinea pigs I admit) but she exposed the bad practice on Twitter, even publishing trust letters of frightening inappropriateness. I still blame myself by not objecting more, although in my own tweets bringing attention to hers, I did tag in TEWV.

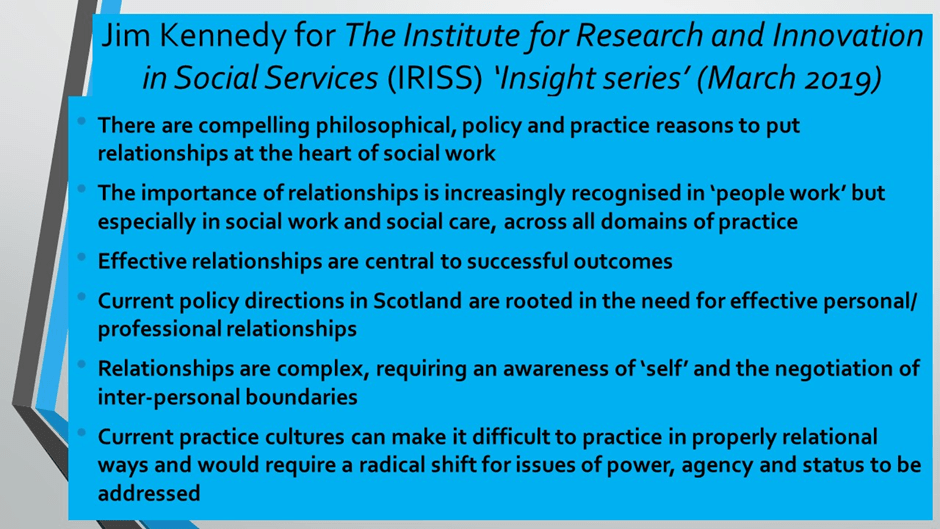

Finally, before the bibliographic slides, a link is given to practice guidance on relationships in the light of all that ii follows. The text of the IRISS document will be available on Teams (and is linked here). In class we will end with free wheeling discussion of Jim Kennedy’s key points in last slide.

Finally for further reading and bibliography. The learners will have easier link access via Teams. I also attach my own Fagan blogs. This writer is a force for good. For access repeated here:

- https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/09/26/how-theres-still-a-kindae-fuckin-serious-as-fuck-splendour-tae-every-minute-ay-aw-ay-this-this-blog-contains-my-personal-views-of-jenni-fagans-202/

- ‘I say I am a witch, but it is not what I really believe. We are just women with power and skills and an innate knowledge’.[1] This is a blog on critiquing the telling and hearing stories of ‘witchcraft’ in Jenni Fagan’s (2022) Hex Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd. @Jenni_Fagan – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home. blog)

- A definition of an Ootlin by Jessie Kesson: “queer folk who were out and never had any desire to be in”. The novelist, poet and dramatist Jenni Fagan speaks of her upcoming memoir called ‘Ootlin’ and the origin of that word in the writer Jessie Kesson at a reading performance of her adaptation of Kesson’s BBC Radio Play ‘You Never Slept At Mine’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

- Liberating resistance to the maintenance of the ‘very fragile fucking structure’ of accumulated culture and its oppressions.[1] A preliminary set of comments based on a first reading of Jenni Fagan’s (2021) ‘Luckenbooth’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

- Reflecting on Jenni Fagan’s ‘Pluripotent’: A short Story in Sabrina Mahfouz’s (ed.) anthology (2019) ‘Smashing It: Working Class Artists on Life, Art & Making It Happen’ – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

- https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/08/30/reading-jenni-fagans-truth-the-truth-is-out-and-in-there-jenni_fagan-truth/

Much love

Steve

One thought on “A blog on my second lecture to a Human Growth and Development Course in Social Work (Sample Lecture 2). ‘Attachment Theory & understanding how humans develop & grow relationships over the lifespan: Perspectives on Human Growth and Development for Social Workers’.”