On seeing the Tate Modern EY Cézanne exhibition on the 29th November 2022 and the salutary effect of being much more puzzled about this artist by seeing their pictures as they were painted. An addendum to the blog done ‘prior to visiting the exhibition’. Link to original blog (from September 30th) just above opening paragraph of this new one.

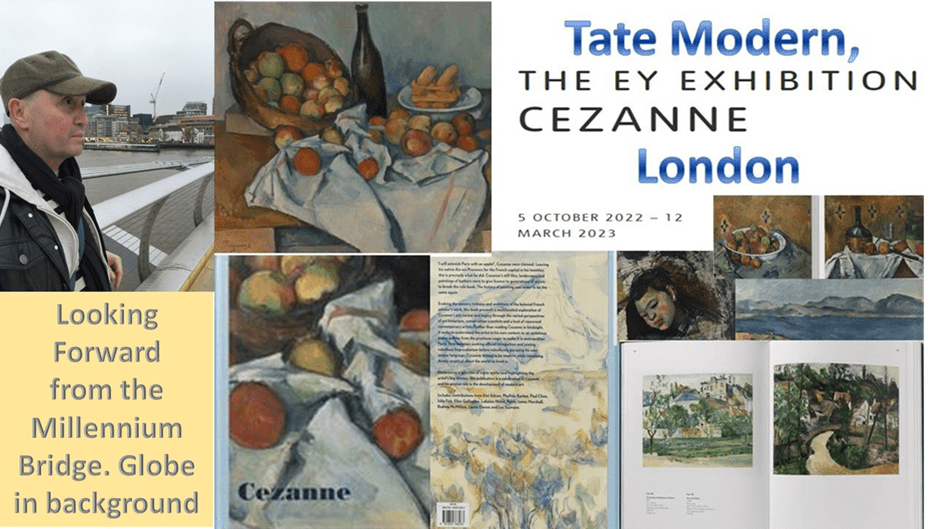

Justin, the hardback book cover and some extracted openings of the catalogue for the EY Exhibition 2022 on Cézanne.

In my original blog I quoted Caitlin Haskell saying that the artworks of the group around Cézanne ‘interrogated and laid open fundamental aspects of picture-making – colour, facture, finish, resolution, subject matter, cropping, compositional structure, … – to a degree that painting itself became a critical pursuit simultaneous with its creative and aesthetic ends’[1]. It remains I suppose a lesson about these pictures that remain, but I feel less sure of myself with this lesson and less able to come to conclusions. I saw this exhibition with Justin yet our mutual thought processes tended to stop at admiration than move onto into explication and application to our lives. Of course this may be because it was an exhibition seen after a walk across London from Kings Cross and Euston Stations (endpoints of our different journeys from the North, determined as we were to approach Tate Modern from the Millennium Bridge and, at least view the Wanamaker Globe. No doubt we saw them in a tired state.

As I reflect over the photographs I took I started forming collages that reflected some of the puzzles that remain with me about how and why I just love Cézanne more than his peers yet still cannot truly articulate why. I had wanted to see the Mount St. Victoire paintings I had not seen and comparing them is a good start to the puzzling but highly appealing nature of the artist’s vision of the worlds around him. I use the word ‘vision’ with caution for that might suggest that the differences of ‘take’ on the one topic and space was perceptual rather than being a matter of facture. For what we see is much more differences of compositional design and choices of colour and forms, as well as decisions about elementary mark making, that begin to facture that ‘vision’.

That is why I think there is something haptic (eliciting at least the imagination of touch) in these paintings. Whilst sometimes yielding to the effects of viewpoint, the difference in paintings are between the choice of shapes, colours, their partial overlay and interaction in that method they call a ‘passage of paint’. Justin and I played with the term geometric to describe the method of fitting together shape but it is only partially successful because geometry, despite Cezanne’s championing of geometric form, avoids the interactions between shape and colour, and between different shapes and colours. The green of the landscape invades the sky in my favourite picture, forcing the ground to be satisfied with dry partially regular stone-scape as its predominating marker.

I see this strongly in Cézanne’s many roof-and-tower-scapes with utilise the lateral and vertical assumptions that cluster around cognitive prototypes of rooves and towers (or chimneys) to force ideas of how space is distributed in a painting’s design and allow for interactive combinations and colour palettes – whether dark blue-grey against softer evening blues or light pink-red in effect against bright sun-lit sea. I do not know though know how to develop that idea. But do I need to.

Extreme versions of the reliance on passages of paint can be seen in these two scenes and details from them. We can imagine these as impressionistic paintings based on the capture of lighting conditions but I do not wonder that critics often seek over models of descriptions, such as geological layer in and compounding of stones over massive durations. It is not just colour and paint it is the direction of application of the marks and the choice of blanks as non-finito outcomes.

It is because of the artist’s experiments in the application (and applicability) of different artistic media) that we can’t easily see him as entering into the traditions of a genre without transforming them, as in the still lifes below. Whereas still life, in Golden Age Spain for instance, had insisted on the trompe l’oeil effect of creating the illusion of folds in cloth, Cezanne seems intent on suggesting them (in the example on the top right for example) by the absence of markings ( by blankness in his passages).

Where precision is attempted it is achieved but design of the flat surface predominates over illusions of perspective, such that the eye feels a lack of stability and balance, feeling potential motion in the apples that might be in motion rather than just arranged and periling the china sugar-pot. In later oils the effect of instability is caused by thick oil impasto and gives objects an ontological instability, a flickering at their supposed boundaries.

I suppose that for someone has emotionally and cognitively led as me this dissatisfies for one desires if you are me to apply the learning from internally created emotion and ideas. Justin tells me off about this. I can be on surer ground surely when this exhibitions tries to forefront the possibility that Cezanne might have been actively abolitionist in creating his painting Scipio, of an activist. But what I see here too is the same ‘ontological instability’ in things, in clothes in particular – hence the details below. Hence I wonder if Cézanne was ever stable enough mentally to run from what he tried to facture into vision into real world action, especially political action which depends on simplifications. Do you agree? Take a look.

In depicting gender difference, there is even more puzzling perplexity in Cézanne’s work. Cézanne claimed to paint more male than female nudes because the former were more easily available. But there is such a tendency from what I saw to see female groups as examples of design patterns rather than interesting in themselves, especially as individuals. Here the geometric imposes pattern over complex passages of paint, to which the female anatomical and pose are leant. We strain to triangles or rectangles in these groupings. What commands our interest within such shapes are the passages of paint that interact in the marks rthat indicate settings of the scene.

This tendency in group portraits does not happen so much in groups of male nudes, where differentiation of individuals predominates over the group shapes they make. Indeed, unlike the women above, these men seem locked into their own worlds. So much is this case that we often see them in some individual rather than group activity and often in the process of, rather than being nude. There is unspoken community perhaps but it tends to happen in dyads not larger group forms.

Hence it is the individual male nudes that stand out in this exhibition, especially my favourite one below, although the action of tentative stepping in the process of bathing seems a stock Cézanne trope for it occurs in the group example (the one on the right) above. We are less interest in a static take on male nudity but rather in the dynamism of male bodily motion, even in the most tentative of actions.

These men are so lovely, because absorbed into mark making innovations in painting that emphasise aesthetic interactions within the frame in which alone they exist. There is vulnerability in the individual men but they are not primarily presented as independent of the techniques they sustain in the painting. That ought to dissatisfy me. It doesn’t. Just puzzles me! And the puzzle is even greater in the vision of the earlier art of fragmented impossible fantasy scenes, which defy all unspoken rules of mimetic representation. To combine part of a still life (of pears on folds) with a realistic fleshly nude seems just to play with traditions whilst refusing to become part of them. The painting that became known as ‘The Eternal Feminine’ as a spoof of the Goethean view of the pursuit of an ideal with passion, clearly has ideational content (for the feminine is ensconced in an altar-like shape by bishops as well as artists, Musicians and possibly circus acts are there too . It offers me no way in to the artist but intrigues.

There is no doubt that both Justin and I enjoyed this exhibition, but unlike the Freud it did not spark art-focused exchanges between us. Nevertheless I am extremely happy to have seen this for if nothing else is clear, that Cézanne is a master pre-empting Picasso and others is. So do see it.

All the best

Steve

[1] Caitlin Haskell (2022: 35) ‘Cézanne’s Refusal’ in Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (Eds.) Cézanne London, Tate Modern & Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 35 – 48.

One thought on “On seeing the Tate Modern EY Cézanne exhibition on the 29th November 2022 and the salutary effect of being much more puzzled about this artist by seeing their pictures as they were painted. An addendum to the blog done ‘prior to visiting the exhibition’. Link to original blog (from September 30th) just above opening paragraph of this new one.”