On seeing the National Gallery Freud retrospective exhibition ‘in the flesh’ on the 30th November 2022. An addendum to the blog done ‘prior to visiting the exhibition’. Link to original blog (from October 5th) just above opening paragraph of this new one.

The original blog is available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/10/05/the-credit-suisse-exhibition-lucian-freud-new-perspectives-is-according-to-laura-cumming-the-artist-stripped-bare-freuds-portraits-can-speak-for-themselves-this-blog/

The Credit Suisse Exhibition 2022 on Lucian Freud webpage with cover & some extracted openings of the catalogue from same website: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/the-credit-suisse-exhibition-lucian-freud-new-perspectives .

That seeing art ‘in the flesh’ is a superior (and for some the ‘only’) method of knowing a work of art is an assumption often in art criticism. In an M.A. History of Art course I did no voices to the contrary were allowed air space to even add nuance to this assumption. Hence, embittered (lol) by this experience, I have frequently addressed this assumption in earlier blogs. The bitterness in particular creeps out in all its ugliness in this section of an earlier blog on a book on Martin Gayford, whom I admire immensely I have to say:

Nowhere were these easy assumptions as clear in the assumption that the true object of study in the History of Art was art seen ‘in the flesh’, although it was sometimes [my argument when I studied the subject] that this was a convenient belief when middle-class History of Art students wanted to boast about expensive foreign holidays whilst [apparently]evaluating them as pilgrimages to the source of the only genuine knowledge to be had of a masterpiece that is stored in a remote place. Gayford’s use of this fleshes out, so to speak, all the meanings that can be drawn from the phrase and the ambiguity in its common applications to argue their aptness to the works of Lorenzo Lotto. Here is a fuller version of the quotation:

There is an odd but revealing phrase – ‘in the flesh’ – for seeing art in reality, not reproduction. With Lotto and other Venetian painters it’s almost exact: to appreciate them properly you have to stand in front of them. Only then can you sense the carnal reality of the people they depict, the glistening of the skin, gleam in their eyes. the weight of their bodies, the texture of their clothes. These are physical experiences, because paint is a physical substance: a layer of organic and inorganic chemicals that reflect the light, and consequently change every time the light alters. There is no substitute for being there.[3]

Used lazily, as it usually is the meaning of the phrase in the casual discourse of art historians it means exactly and only the meaning given it in the second sentence here – it emphasises that to see the reproduced image of an artwork cannot allow us to claim we know about or even have seen the artwork. As the definitions in the appropriate webpage of vocabulary.com shows, when used thus it works because the term ‘flesh’ is a synecdoche, a form of metonymy wherein a particular part of a person stands for the ‘whole person’ and its meaning can therefore be satisfied when it applies only to the person talking about their experience, when it references oneself not the thing or person seen.

However, extensions of this definition, and indeed most of the concrete examples given in vocabulary.com apply the term to the object or person seen, in which case ‘flesh’ is also a metaphor, which sees an inanimate object, a painted canvas, as if it too were a person. Gayford uses this ambiguity to shift our attention from the person seeing to the notion of a meeting between persons, where both are embodied, which easily shifts to a reference to an application to the body of the figures in the painting. When we see paint in its physical reality, it is a kind of flesh that makes the people themselves in the painting as alive and fleshly as the viewer, a ‘carnal reality’. It is worth lingering here, seeing the term ‘carnal’ though it literally refers only to flesh has the association of something appetitive, that must, in some sense undress the viewer as address the viewed figures. Of course I take this too far but it is exactly how art gains the depth of embodiment – the feel of texture and opaque but soft resistance – that Gayford refers to. However to say that this is the only way of seeing an artwork is clearly wrong.

Moreover, even in this passage, but also elsewhere in other places in the chapter and book, it is clear that just ‘being there’ is not enough to capture such embodied and relative perceptions of the artwork, because after all, the quality of paint is not just to capture the feel of flesh but reflect light which ‘consequently changes’ the image of the artwork seen ‘every time the light alters’. There is a sense, of course that no one visit – or indeed any finite number of visits – would comprehend everything intended by the artwork, even if we confine ourselves to interpretations of its surface appearance alone and not to matters of compositional design.

https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/10/05/the-credit-suisse-exhibition-lucian-freud-new-perspectives-is-according-to-laura-cumming-the-artist-stripped-bare-freuds-portraits-can-speak-for-themselves-this-blog/

My expression is rather unfortunate here and bears the scars of what it is like to take a contrary view to a schooled majority in Open University ‘forums’ (sic.) as they call them, usually policed by teachers who firmly believe that the role of a student is to mislead other students. Yet it does make the point that seeing art ‘in the flesh’ is an inadequate understanding of how viewers process seeing the artworks they view; a process which depends upon the interactive nuance of many factors. Yet it survives as a phrase because the cognitively miserly way humans prefer to think loves to represent the world as explicable because how we see it falls naturally into binary rather than multiple alternative points of view, one of which binaries can be asserted as superior to the another (in this case art seen ‘in reproduction’ or ‘in the flesh’).

Among the variables that complicate this binary are the circumstances of the visit (variations in lighting or atmosphere for instance) and the social context of seeing the artwork. I have often found I see a work differently based on the effect of others, especially significant (but not only those) others, which often is involved not only in articulated exchanges between those visitors but the cognitive, emotional and sense associations of that other or the particular circumstance. And there is, of course more to the nuances than those examples but I needed this preamble to lead to the fact that I saw this exhibition with Justin Curley, whose presence I have grown to value. Hence this addendum will cite sometimes his articulations, or even less visible interactive ways of communion, about seeing art.

I think this is the more evident in the fact that, having walked from our hotel in Lambeth, the one across from Lambeth Palace on the road leading to Lambeth Bridge, we breakfasted so comfortably in the Caffé Concerto in Whitehall in order to make our viewing time. That moment when friends comfortably rest weary bodies and feed them must have much to do with a contentment of the flesh that followed, and which hones perception to the sense of well-being, and perhaps the signs of its potential absence, in the work we were about to see. I am playing devil’s advocate in suggesting that a healthy breakfast and exercise caused both of us to share an openness to the import of the flesh and embodied response in Freud’s paintings,

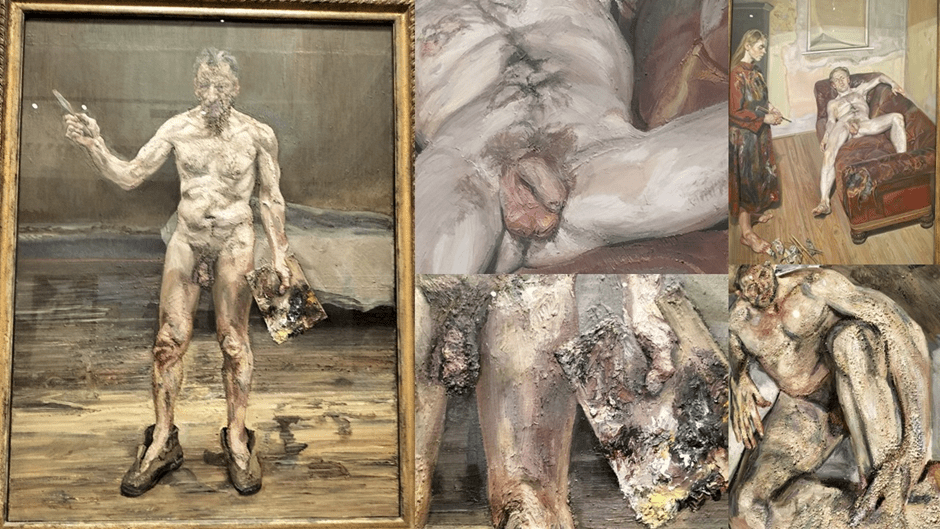

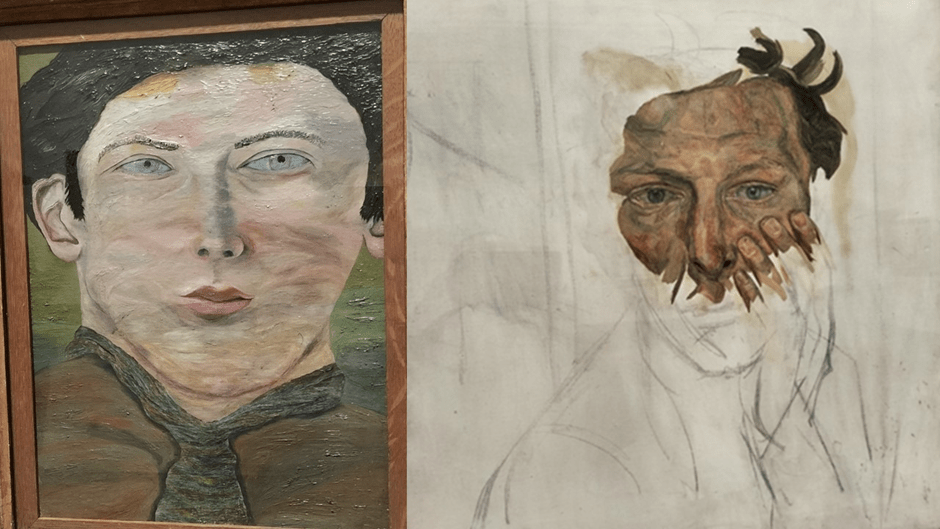

Of course male appetites are ambivalent in effect, even if we confine them for a moment to appetite and desire for sustaining food and rest. Does food and rest truly feed and renew the flesh or stodge it? As I carried on thinking this was not unlike the conversation Justin and I had had in the Caffé Concerto and I cannot believe that some of the responses to Freud’s representation of his own face and body did not feed off thatand the concerns that we both had as very different specimens of masculinity, to Freud and each other. Nearly the first painting we saw of Freud is a very early Self-Portrait from 1940 (it’s first in the catalogue too) in the deliberately naïve style using thick impasto fostered by his then mentor, Cedric Morris.[1] Herrmann speaks of this painting as typical of Freud’s methods of ‘pigment-laden perspectival distortion’ when he references it in terms of his discussion of Freud’s later fleshy models like Sue Tilley and Leigh Bowery, but there is more than ‘overt display of surface and process’ in this comparison, for this early painting render’s Freud’s appearance as being not only flattened but fattened and hardly the slim youth we see in the contemporary photographs collected in William Feaver’s biography. There is too much ‘too, too solid flesh’ here that, as paint, seems to overfill its frame.

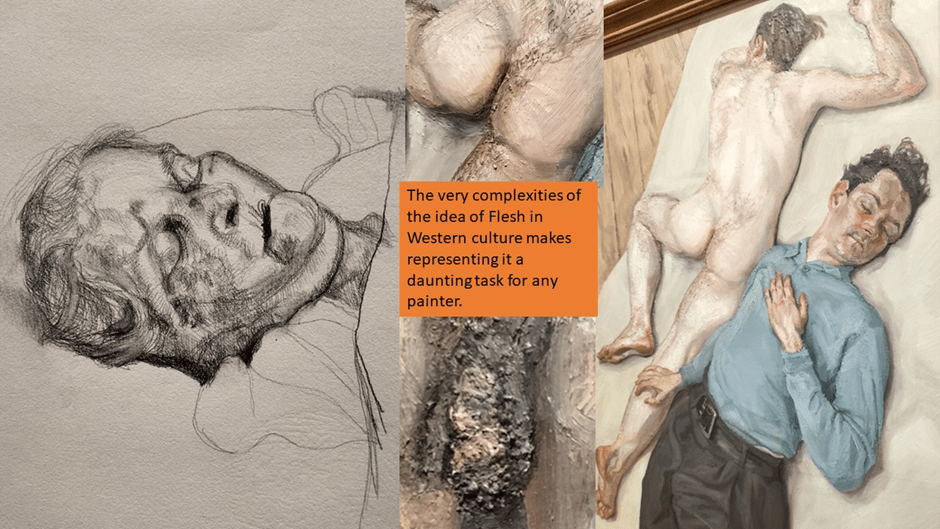

Unfortunately I give only a thumbnail in the collage above of this painting but to see it (see it a little better at this link) is to feel the force of flesh uncontained by outlines and seeming to flow like disturbed water into pools of white or bruised pink flesh that seems to emerge from out of the face, destroying any sense of shaping and defining shadow – for even the shadows flow rather than define. There is something I felt of self-loathing here, a view I shared with Justin who though that later self-portraits took on the very control of the artistic medium (and consequently self-representation) missing here. My other examples in the collage illustrate this.

The 1948 Self-Portrait with Hyacinth Pot is as narcissistic as it is controlled- in the sharpness of the apparel, the attention to detail offered by well-defined lines, boundaries and face-shape defining shadows. The hair looks controlled in its unruliness and has a sharp and unrealistic linear boundary with his face. The choice of a Hyacinth seems to me a part of this, for this is the flower into which Apollo’s lover (Hyacinthus of course) was metamorphosed having been accidentally killed by Apollo (with some issues about whether the modern hyacinth is the same plant intended in the myth) whilst both men were at sport. As he ages the control becomes more the creation of perspectival distortion, supposedly enabled by the use of a mirror to show his image with two of his unruly, extravagantly full-fleshed and disordered (in appearance at least) children. Of course I describe the 1965 Reflection with Two Children (Self-Portrait). The shadows over-defining Freud’s face here limit any sense of flesh, since it is totally subdued by its controlling form and the effect is not only chilling but self-chastising; controlling and patriarchal in its feel.

Yet flesh, as we see above so often is linked with self-disgust, or disgust in the other whilst celebrating it (as in Sue Tilley and Leigh Bowery). How much Freud was in control of these variations is uncertain I think. For instance, as I said in my earlier blog, artist Chantal Joffe in her interview (conducted By Daniel F. Herrmann) feels that Freud’s contentment with his own flesh is ‘also sort of monstrous’. She implies that this is because it says a lot about male narcissism, as perhaps a common trait gifted by patriarchal culture in which the man representing his own embodied self is keen ‘on showing himself as virile, hot guy’. She goes on to say that, for a female artist, this take on the body is ‘hard to stomach’ and elaborates what she feels is wrong about that representation. I think we might see that in the collage above where I have given a detail of how Freud builds his own represented penis out of layered impasto, even emphasising this by aligning it with his hand holding his palette of paints. The same layered mess predominates:

The ego. I’m struggling, as a female painter, as a woman. I think it’s the penis and the palette knife – the whole brush / penis sort of contraction. And then the bed behind him! In another way, you could see it as a kind of allegory of him fighting age and not going gentle into that good night.[2]

Joffe’s embodied responses to gendered issues of embodiment speaks out clearly here. Her very ‘stomach’ responds to flesh whose significance is highly concentrated, as is true of this painting, in the working of the penis in thick layered accumulations of paint. And this is not alleviated in that it is also potentially allegoric, as Dylan Thomas’s cited poem is of fighting mortality whether as the aging of the flesh or its death. Flesh and mortality are linked in Western culture and the recourse to some kind of avoidance is in the appetites that feed health and sexual reproduction.

The same impasto blurring happens in the 2011 portrait of David Dawson in my collage, witty called Portrait of the Hound, since the dog’s portrait is, this time, non-finito. The whole of Dawson’s flesh is cracked and scarred by heavy layered paint application. Freud’s jokes often extend the flesh-paint analogy into less obvious signs of the vulnerability of masculinity, even at its most ‘cocky’ so to speak, as in the portrait of Celia Paul painting the portrait of one of her queer male friends, in which the angle of brilliantly defined penis and gonads are mirrored by a tube of oil paint been accidentally squeezed and discharged by Paul’s foot.

You have to dwell on Freud’s obsession with flesh as a symbol of disgust at human mortality, so riddled through Judaeo-Christian Western culture where ‘all flesh is grass’. Paint only gives a semblance of stilling the progress to death, and I offer an even more prominent detail from the 1993 Painter Working, Reflections (already seen in the collage ABOVE) below with the penis alone. Beautiful, this flesh is not, even seen at distance, and the idea of mortality is as present as in his drawing if his dead mother, done immediately after that death.

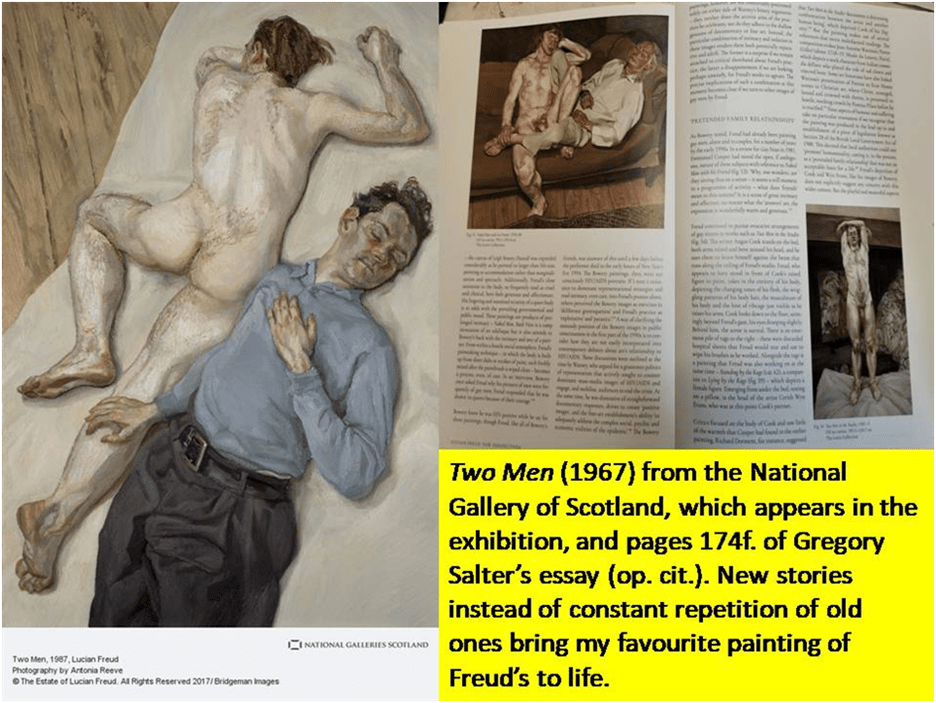

Where formal beauty is intended as in (one of my favourite paintings) Two Men of 1987-8 IT inheres in contrasting position and the forms created by the two men and the hand of the clothed man linked to the nude. But although this is the most beautiful picture of the male anus I know, standing clause to, we see it conveyed by heavy hatching caused by layered impasto effects. There is a rather disturbing line created by the mottling which is tinged with dark suggesting something unhealthy that starts in the lower back and proceeds down the nudes extended leg. It perfectly represents flesh, especially from distance, but it also draws one into the blackness of the anal crack in ways that can’t be easily articulated as pleasure or disgust. My own feeling is that Freud’s capture of beautiful male flesh that also, and only partially, disgusts has much to do with his complexly repressed and often point-blank queer feelings. In a relationship described by a third man, Kentish, as a ‘marriage’ with Stephen Spender in 1940, the time of the first known Self-Portrait, a letter to Spender, summarises their fantasy relationship with they knew as that of “Freud and Schuster”. He remembers it jokingly ass ‘the monotony of waking up in a cold room to find myself with Clap, D.Ts, Syph or perhaps a poisoned foot or ear’. After imagining himself in a nursing home with ‘pus running out of his horn’, he concludes:

When I look at all my minor and major complaints and diseases (sic.) I feel the disgust of which I experience when I come across intimate passages in letters not written to me.[3]

All we conclude from this is that Freud’s response to the body and to intimacy was passages which evoke disgust even whilst they invoke ribaldry and delight, even beauty. This goes to for passages of paint in his work such as that describing the penis and anus and his dead mother above.

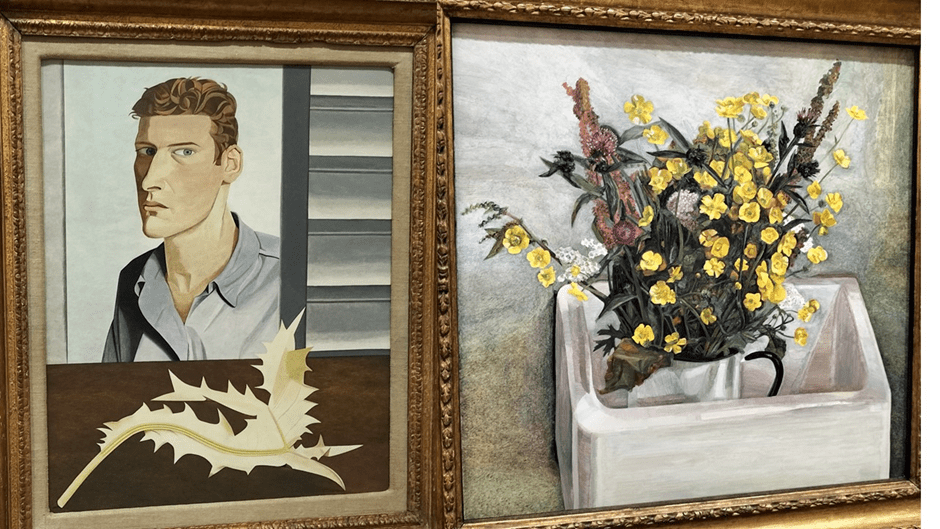

In a sense I think the best revies prepared me go those, such as those by Laura Cumming and Jonathan Jones. I cited in my blog Jones assaying:

Freud paints life in the face of death. In his 1968 painting Buttercups, a jug stands in a sink, stuffed with flowers. I’ve always wondered why Freud’s portrayal of plants always seem so sad. Looking at this, it’s suddenly clear. He pays such meticulous attention to each little yellow buttercup: this isn’t a painting of flowers in general, not even buttercups. It’s about these single specific buttercups – and they’re dying.[4]

In both paintings in my collage the beautiful is also the dying and out of place, and sometimes prickly. It is about appetite for beauty edging to disgust (the flowers are in a sink) and hard-to-understand passages. For Justin and me, I think the sum of our conversations as I reflect back were on the coming to terms, each of us for different reasons, of our own masculinity which we distrusted as it is inherited but still valued enough to want to identify with. I think this is healthy, but its symptomatic show in Freud – control, disgust, the treatment of women as children as objects in one’s life – is not always healthy. The more reason that is, of course, we all, well especially men, need to consider it.

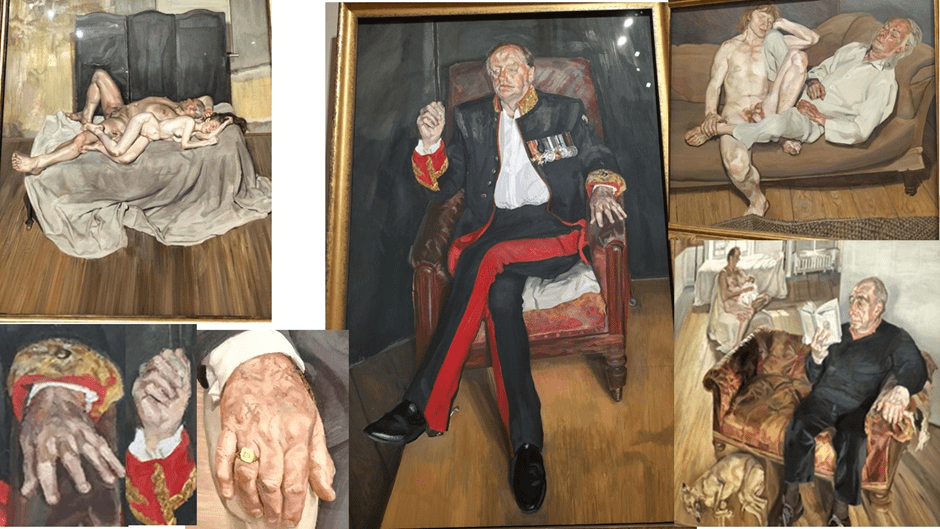

One of the features of this exhibition, because it is of Freud, is the use of incongruous pairings that query the meaning of what it is to expose the body to another, which is conveyed sometimes by painting models as if they were together in a sitting when they were not. The dual naked portrait of Leigh Bowery and a naked woman who has turned from him apart from resting a foot on his ample leg, seems to emphasise the beautiful isolation of Bowery, as well as the prodigious size of his penis. When two men or two women are shown together it is often in figures differentiated as clothed and naked. It feeds into, Gregory Salter confidently asserts, the contemporary debates on ‘pretended family relationships’ as queer relationships are described in Section 28 of Thatcher’s notorious Local Government Bill. This is tested in real relationships, as in Naked Man with Friend of 1978-80 in the collage above. But in the same collage is the painting yoking two men directly in a family pretence, with children and David Dawson’s dog again, which they were not in (Large Interior, Notting Hill). I found the last painting endlessly hard to explain (or ‘…elusive, You can never quite explain them’ as David Dawson says)[5] though Justin shared with me aspects of the painting that suggested it was a bitter joke played on one sitter.

I still struggle, like Laura Cumming does, with Joffe’s idea that The Brigadier (2003-4), a portrait of Parker Bowles, whose late wife is now our Queen Consort, that ‘though this figure is completely dressed, this is perhaps the most ‘naked’ human that I’ve seen in a Freud painting’. However Joffe has a point for the Brigadier’s body keeps emerging from the frame his status tries to give it: ‘the bulge of the tummy over the trousers and the beaten-down face … a kind of pomposity’. [6]

Even when men of power are naked only in their hands and face, as with the Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza too, they are naked emblems seemingly of power which seem too to have taken on the vulnerability that flesh is heir too. They apparently rest and are still but seem instinct with uncontrolled emotion. I started of by saying that Freud tried to control that wanton flesh shown in his 1940 self-portrait but even in a later non-finito portrait the fleshy face tries to emerge out of lines that might have contained it. I think Freud never quite resolved this. Look again at these paintings:

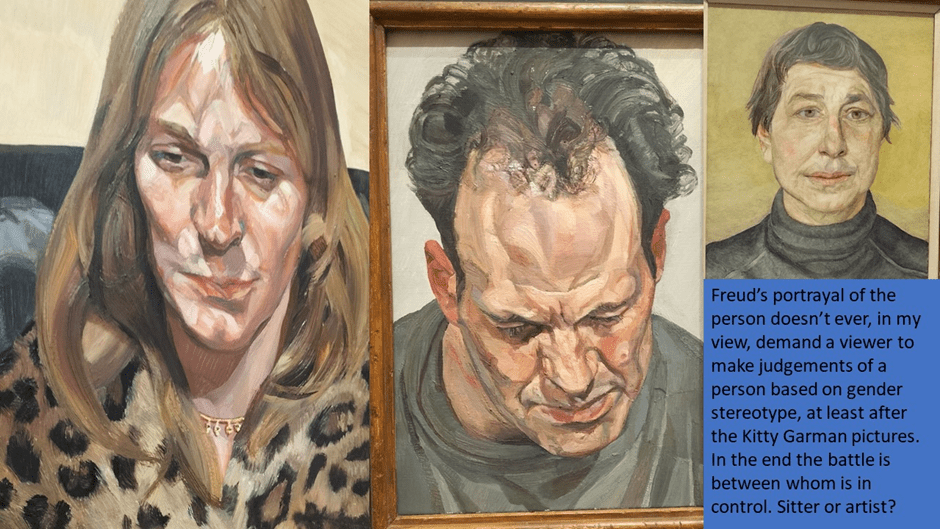

With exceptions such as And The Bridegroom, the mature Freud’s portrayal of the person doesn’t, in my view, demand a viewer to make judgements of a person based on gender stereotype, at least after the Kitty Garman pictures. In the end the battle of his painting is between whom is in control. Is it sitter or artist?

All three of the paintings above are immensely respectful and of the person whether they are an artist or no, burdened though they are with flesh (and painterly brain in Frank Auerbach’s case). The gender coding is complex for shadows can lend confusion to some of the certainties thought to be therein. Flesh is celebrated and haunted by the potential of its own losses in all cases. What these people see or don’t see is not a matter of gendered preoccupation. Woman in a Fur Coat (1968) is much more than a horse for gendered clothes and jewellery, despite the luscious detail of their depiction. She contemplates with melancholy a whole life in ways that the other two, though these are both artists, do. They are why I sometimes love Freud quite uncomplicatedly.

This exhibition nears its end. Its better than I, or even Justin and me, can say. See it if you can and ‘in the flesh’.

All the best

Steve

Addendum: Blogs mainly about Freud

Blogs that include Freud

[1] Daniel F. Hermann (2022: 15) ‘New Perspectives: An Introduction’ in in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed.) Lucian Freud: New Perspectives London, National Gallery Global with Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 12 – 28

[2] Chantal Joffe in Daniel F. Hermann (2022: 183f.) ‘“Flesh is paint and paint is flesh”: A Conversation with Chantal Joffe’ in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed) op.cit. 181 – 184.

[3] William Feaver (2019:109) The Lives of Lucian Freud: Youth London, Bloomsbury Press

[4] Jonathan Jones (2022) ‘Lucian Freud review – the Queen, Leigh Bowery and the artist’s ex-wives stand brutally revealed’ in The Guardian (online) [Wed 28 Sep 2022 00.01 BST ] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/28/lucian-freud-new-perspectives-review-national-gallery-london

[5] David Dawson cited (2022: 85) in ‘Painting as Waiting: A Conversation with Tracey Emin and David Dawson’ in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed) op.cit. 80 – 86.

[6] Chantel Joffe op.cit : 184

One thought on “On seeing the National Gallery Freud retrospective exhibition ‘in the flesh’ on the 30th November 2022. An addendum to the blog done ‘prior to visiting the exhibition’. Link to original blog (from October 5th) just above opening paragraph of this new one.”