‘Transgression and deviance are no longer universal but local, temporary and up for debate. / … / The bawdy human, indulging in an excess of all these biological functions, addresses the threshold between how things are and how they could be if only we could get over the hang ups and let downs of daily life’.[1] This is a blog exploring, from my own point of view, the limits of using the biological or ‘animal’ functions, especially in relation to sex, as an argument for liberation of the oppressed and marginalised, however much fun that approach yields. It uses the book / catalogue of a Tate Britain exhibition in 2010: Tim, Batchelor, Cedar Lewisohn & Marin Myrone (eds) [2010] Rude Britannia: British Comic Art London, Tate Britain.

The cover of the book / exhibition catalogue by Tim, Batchelor, Cedar Lewisohn & Marin Myrone (eds) [2010]: Rude Britannia: British Comic Art London, Tate Britain..

Sometimes the arguments for the liberation of queer sexualities get simplified by their opponents, and perhaps even, sometimes, by proponents. There is an argument that since the notion of the transgressive and / or deviant is socially constructed, which it undoubtedly is (and not least when it marshals outmoded hypotheses, such as the binary nature of sex/gender, and calls them ‘scientific (and especially biological) truths’, it sanctions the performance of any act, thought or discourse that transgresses all or any ethical code. Sally O’Reilly in a very short essay in this catalogue does not say that as such but the case is almost put in a section of her argument I refer to in my title, which invokes Aristotle but does not elaborate on the implied and complex notions Aristotle’s cited words raise. In a catalogue we would expect no more. To give the size of O’Reilly’s intervention, I give an important summary maxim of how, it is argued, the late twentieth-century and perhaps before, understood local changes in the mores of social and private life and the whole of the last paragraph of the essay.

Transgression and deviance are no longer universal but local, temporary and up for debate.[2]

/ … /

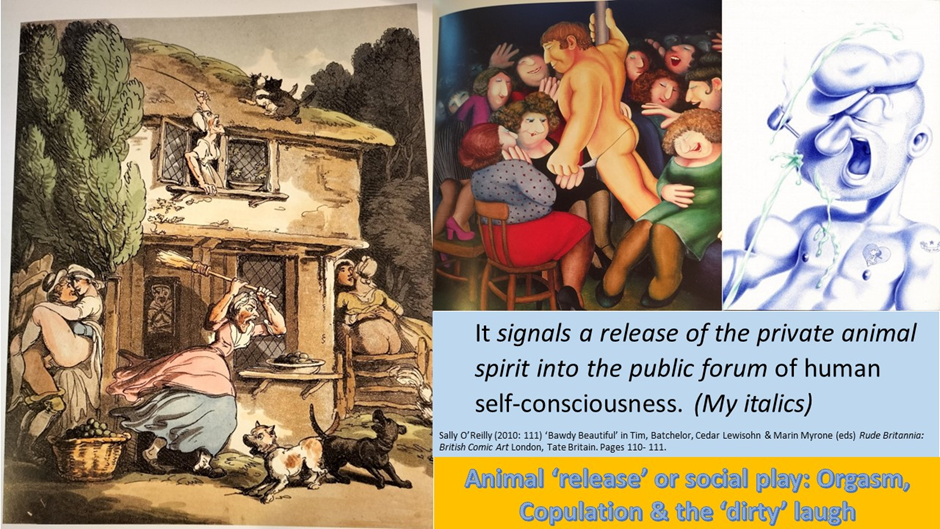

Humans are one of the few creatures that engage in sex for pleasure, and , what is more, it is though that we are the only ones that laugh, weep and blush, too. Aristotle suggested that this is because humans can understand the difference between how things are and how they should be. The bawdy human, indulging in an excess of all these biological functions, addresses the threshold between how things are and how they could be if only we could get over the hang ups and let downs of daily life. It signals a release of the private animal spirit into the public forum of human self-consciousness. (My italics)[3]

It is my belief that the descriptor ‘biological’ is too often invoked in ways that are clearly ideological and, in part at least, socially constructed. There is no doubt in my mind that looking at the evidence from comic, and especially bawdy, art can justify the notion that using an event triggered in part by biological systems of the human body is seen as a means of releasing something at essence that is labelled ‘animal’ in human animals, but which may be so in an intellectually lazy way. It is lazy anyway to accept the hypothesis that animals do not have equivalents of the cognitive constructions of what we call pleasure, laughter, tears and shame, just as it is to accept that all humans experience these cognitions for emotional experience in the same way and at all points of history. This argument is in danger of seeing change in the way the transgressive is configured in relation to norms as stopping short of anything we label biological. In fact the examples in this catalogue suggest this is far from the case.

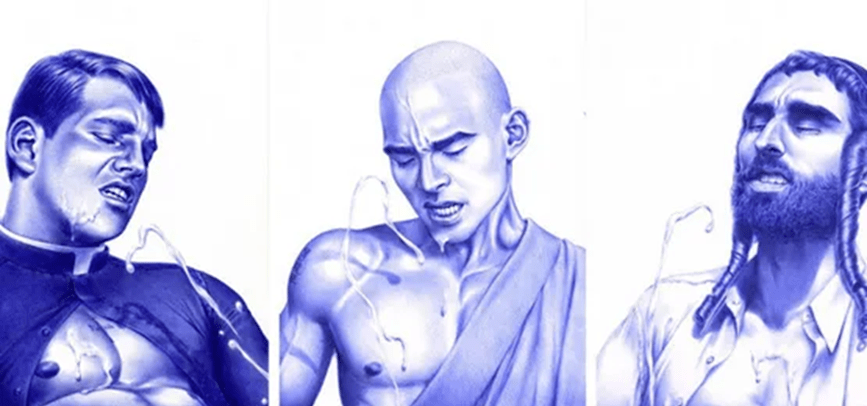

The degree to which ‘the animal’ (within the human animal) might be invoked to explain the pleasure or fun of sexual activity varies in these examples. Moreover the degree to which the activity can be explained as the purely physical release of the internal into the external world in response to external sanction or disapproval is also a variable here. Orgasm is according to O’Reilly in a statement that owes much to Roland Barthes concept, borrowed from Lacan, of jouissance, although again this is implicit, is the ideal example of such release of bliss: which she names ‘a small flowering of triumph in the battlefield of mortality, and the bawdy blows this trumpet loud and hard as a rallying cry for the self-aware’.[4] The dual metaphor of warfare and natural flowering work hard here. Clearly this idea might be silently conveyed best in Cary Kwok’s (2007) Here he Pops, which exploits one of the urban meaning of ‘pops’ (as indicating orgasm) to complicate the identity of the comic character, Popeye. Kwok delights that the Popeye character can be seen complete in wearing his badge of heterosexual identity, as a heart-shaped tattoo bearing the image of female lover, Olive Oyl.

The aim of Kwok’s ejaculating heroes however is to assert not moments of ‘private’ release from the supposed ‘public’ strictures that a sailor’s (even imaginary ones) absence, and morality, put upon them but to feel supportive affection from a viewer (for Kwok’s characters exist to be seen, known and loved in public just like the cartoon characters and iconic male superheroes he often chooses). The tattoo on Popeye’s arm bears Cary Kwok’s name and the image has a great deal of homoerotic coding in the delivery of the open torso to an appreciative gaze: what seems to be going on here is that any sense of a distinction what is thought to be a private or a public act is being confounded and indeed made part of the dynamic of pleasure.

Some of Cary Kwock’s ejaculating male icons. Collage available at: https://www.widewalls.ch/artists/cary-kwok

Indeed when interviewed by the digital magazine Frontrunner by Shana Beth Mason in 2019 Kwock endorsed this view of this art as being in part about the vulnerability of a lonely male in a supposedly private space, with eyes shut; vulnerable because of their biology not being validated by it, looking for social validation and not just sexual release. He says:

To me, along with affection and tenderness towards people you love and care about, a man ejaculating is one of the most beautiful and erotic things to witness, whether or not you’re engaged in the actual act, and whether you’re the one watching or the one being watched. The intense excitement of the dynamic of both parties is indescribably intimate. You’re allowing your vulnerability to be exposed to another person, your senses are excited by this visual stimulation – knowing you’re being watched intensifies the experience. That beautiful, fleeting moment is captured forever in my work, even when the act is complete in my realm of imaginary spunky men. My subjects always have the viewers to lean on / curl up to. We hope we’re good enough people, we don’t just abandon the person who’s just cum for you.[5]

The relationship hence is with the viewer (Cary Kwock being as absent in that moment as is Olive Oyl) who will provide momentarily a release from post-orgasmic emptiness. The occasion is social whilst being also on the cusp of social definitions of public and private. This is I think the case too in Beryl Cook’s (1981) Ladies’ Night (Ivor Dickie), where what we might superficially see as a sexual release through laughter, after Freud’s model of the joke, is in fact a moment where the already known (for they already knew this man had a Dickie without showing it visually or aurally in his name – get it ‘I’ve A Dickie’ – releases for the women something like mutual pleasure in each other at the absurdity of hanging such a difference as gender on this piece of flesh. Our joy in this picture is, I believe, in the ability it has to capture female solidarity and mutual fun at the expense of men in part. The public and private as a constituent part of sexuality despite biological function is I think one of the meanings, whether intended or not, of Thomas Rowlandson’s 1812-27 Sympathy II, also illustrated in my collage, for this print explicitly looks at how humans and animals have the public and private mediated vis-à-vis sexual coupling.

Rowlandson pictures his dog and cat couples as pairs and although the catalogue summary does not seem to support such a reading, it seems to me that the ‘ageing cottager’ who appears doubled in this picture, pursuing errant animal sex in order to punish it at every orifice of her home. Surely this is the same woman caught as it were showing how she fills her time in surveillance and punishment of ‘excesses of biological function’: the same ageing woman indeed whose portrait is seen peering through her front door. Though the editors of this catalogue see her as punishing the ‘disturbing rumpus’ by seeing it as attributable to the cats and dogs rather than ‘youthful lust’ amongst her workers, I think that this explanation invests too much in the imagination that illicit human sex is noisy like cats and dogs are considered to be by nature.[6] Post coital positions are given to the animals – to me the meaning is clear. The lady punishes visible sexuality, whilst tolerating illicit sex that occurs outside her vision. For this is how the two heterosexual couples having sex are painted – around corners and in shadows, seen only by the print’s viewer.

We clearly are intended to be interested in these couples and their sexual pleasure. The anatomical correctness of the large penis and gonads of the boy on the viewer’s left are made plain as a kind of reward for the viewer, even though they may protest they did not wish for this sight. After all the editors of the catalogue tell us that such scenes resemble pornography produced in France: ‘specialized, secretive imagery intended primarily to arouse’.[7] Yet I see the ethical intention of this piece as somewhat obscure. In a sense, it punishes the older woman in it for her narrowness and the wastage involved in the pursuit of a space clear of visible sex, whilst she allows her young workers to neglect the results of nature in produce – shown in the basket full of plums, which the couple on the left have set down, the more easily to copulate. Is it a warning of the narrowness of the English about the benefits of sex as reproduction (what produces after all the ‘fruitfulness’ of a basket of plums) whilst worrying mainly about excesses of biological function. What the viewer is urged towards is seeing that these benefits of biological function need careful management not tyrannical control. If so, this piece is about neglecting the use-value of her young workers and their energies. Whatever else, it is sure sign that sexuality needs to be in the social sphere of influence not to allow sexual release but to be managed more effectively, because its attractions depend on manipulation of public and private spheres. A cottager who aged into maturity rather than punitive action because her youth is lost would know that: it would be the sign of her maturity.

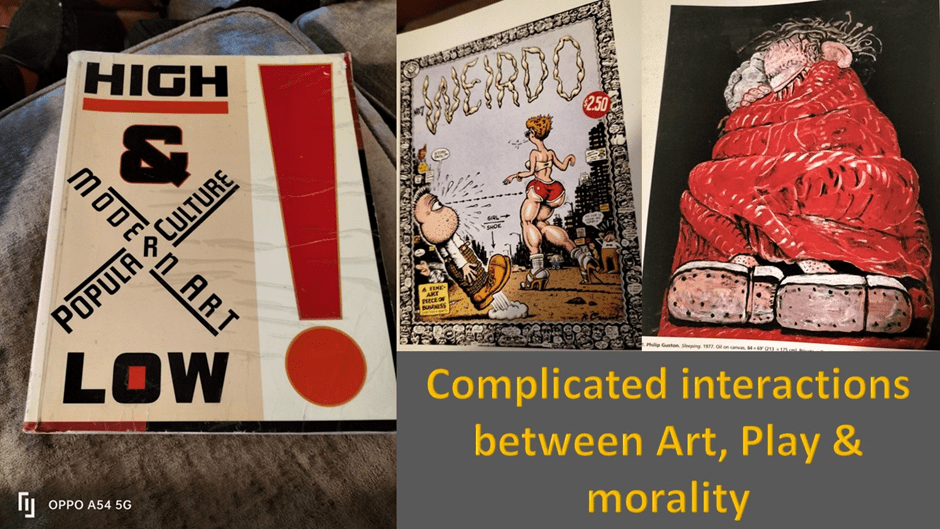

Hence, I think all three examples here show that to use a notion of ‘release’ from social control as sufficient justification for sexually engaged visual art, for their functions are not just biology (and that in excess) but to point to the psychosocial constituents of sexuality. In doing so we never escape ethics, though it won’t be just an ethics of heteronormativity. The issues are even more complex in some interactions between popular comic art and artists within the canon of accepted art in the USA, which I will reference briefly in Kirk Varnedde and Adam Gopnik’s 1991 exhibition publication for the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MOMA): High & Low: Modern Art / Popular Culture.

I will satisfy myself with one particular rich example, for there are many in this wonderful book and its essays. Discussing the development of Philip Guston’s art via its interaction with characters in popular comics, they point to the invention of Cyclops: ‘ Cyclops is Guston’s self-portrait, but it seems to derive from a motif from the comics of the forties: Al Capp’s Bald Iggle’.[8] Cyclops is not Bald Iggle (the latter has two eyes) but has fed off some of its themes of the alienated outsider that could become iconic of the artist for Guston. Yet in Sleeping (1977) – on right of collage above – Cyclops is vulnerable because of his one-eyed pursuit of appetite whilst asleep. This image clearly references the Cyclops of Homer whose one eye will be staked by Ulysses. However a one-eyed giant is and always will be an icon of the phallus (thus Carl Jung saw it for instance in the study of folklore and dreams). For Guston this was a charged image of complex moral responsibility, particularly hanging round his complex closeted queer sexuality, a sure sign that for instance sex can be too intimately tied to naked power in fulfilling appetite without consent in the absence of moral vision. However Varnedde and his colleagues brilliantly show, though not with my commentary extensions, how Robert Crumb undermines those moral questions when he takes the image of Guston’s self-referring Cyclops into his work (he had drawn it first in 1977), and especially in issue 7 in 1983 of his comic magazine Weirdo, which shows Cyclops as a phallus undergoing dynamic erection at seeing a semi-clothed woman on the beach (see my collage).

Crumb though is, I think, clearly of the O’Reilly school and drains Cyclops of guilt and isolation in his complex ethical stances by seeing them as the hang-ups of ‘high art’. On the back cover of the same Weirdo issue: ‘“Oh, what a fool I’ve been,” Crumb has Guston saying, “and will continue to be”’.[9] Calling the image “A Fine Art Piece of Business” Crumb clearly saw Guston’s rich moral complexity as a mistake – what more natural, he might appear to say, than to let the bawdy rip; whenever a biological function calls, there can be no appeal to fuddy duddy conception of either high art or old morality, only ‘nature’. In my own view Crum oversimplifies. As the rich learning about the psychosocial-sexual realm of queer people because of their experience of subtle social oppression always is oversimplified.

Once we have seen the necessity of pulling bawdy or other sexual reference out of the vacuum of ethical thinking, it is clear that with sex as with the other topics of comics explored in the Tate catalogue demands variants of sexual ‘liberation’ that as much depends on a psychosocial as biological argument, for liberal thinking is sometimes thinking that ignores power dynamics that harm the vulnerable. There is a multiple dialectical relationship, I think I would assert, between the biological, the social, the psychological and the ethical in the sexual that needs attention to distributions of power. In the most extreme form the absence of this allowed some in the radical queer movements to give ignorant succour to paedophile movements in the 1980s and which allows ignorant marginalisation of the issues of trans sexuality amongst some radical feminists and LGB Alliance activists in contemporary movement.

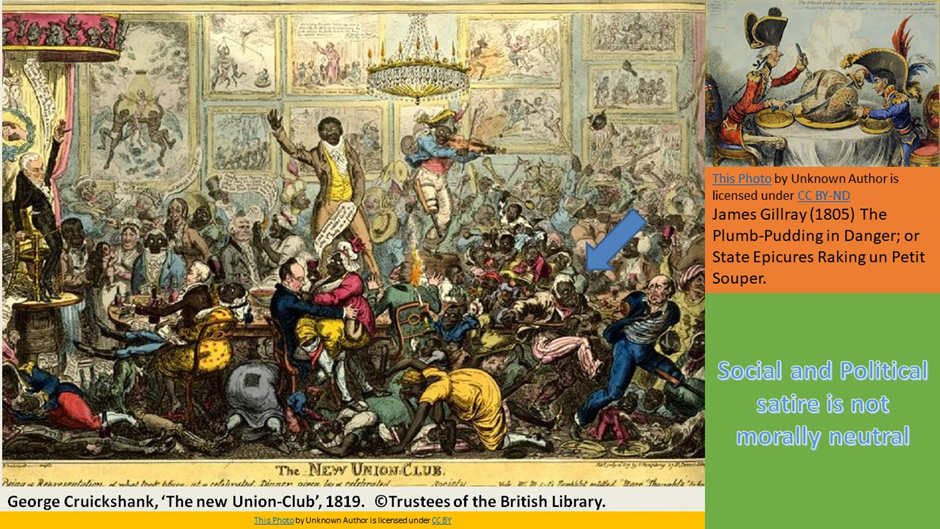

Rude Britannia did not only undermine false sexual moralities but ones related to supposed social superiority or claims to unequal and larger number if rights by the entitled few, to whom being ‘rude’ (in the name of satire, becomes an ethical priority. Thus again Thomas Rowlandson (already mentioned) could scarify something wrongly called British Justice in his caricature The Judge in the 1770s wherein we see a person in an important role to be ‘as gross and foul in his morals as he appears in his person’.[10] In direct application to historical figures in politics it can be salutary as in Gillray’s The Plumb-Pudding in Danger (below). However, this is not a morally neutral act for it depends on dangerous assumptions about the relationship between personal appearance and moral reality that are as utilised in manipulative political schemes on the right as the left, such as George Cruickshank’s scurrilous racism (yes of course that of his age but aimed at persons attempting to tackle some parts of a racist system – the Abolitionist) in his 1819 The New Union Club.

The main target of fun here is the ‘absurdity’ of Black people holding positions of power and social status and which compares Black people to monkeys. In this case this catalogue is spot on about the problem:

Much of the art of visual satire has rested effectively identifying what David Low called a ‘Tab of Identity’. The leading characteristic that seems to stand in for a whole personality (and policy). This has involved the pursuit of striking physical contrasts – between the thin and the fat, the uptight and the dissolute, the small and the large – sometimes invoking existing social and racial prejudices.[11]

It’s an interesting feature of the Tate catalogue that it ends, for reasons whose validity escapes me, with an interview with comedian, Harry Hill, who is an archdeacon of the Belief that you ‘only need to be funny’ not have issues to air, in this sense like Robert Crumb above. Comedy is its own justification but only if it is received as ‘funny’: ‘all you have to be is funny and that’s it. And I think the challenge is to be funny and in a way that other people aren’t’. [12]

I find this as simplistic as the positions about sex I mentioned earlier, and possibly as meaningless for it depends entirely on a dogmatic belief. That isn’t to say that Hill isn’t write that Tommy Cooper’s act is a ‘beautiful thing’ that depends entirely on performance values such as timing. The only requirement both interviewer and interviewed here seem to need to be ‘absurd’ in an original way and that is one way of reading the British Comic tradition. But it isn’t enough surely. Although artist and curator Cedar Lewisohn sails near to claiming that humour must be innocent of interpretable meaning since; ‘Everybody knows that the best way to kill a joke is to explain it’. However, he is not saying that. He knows some humour is ‘ugly and offensive and disturbing’. But to be disturbing alone is not a bad thing. His subtle point, with which I totally agree and is in line with this blog’s aims in that he thinks art and humour may have to ‘tap into a jaundiced view of the world’ if they are to challenge that view and to make art and humour an effective ethical weapons. The thing is not to be simple-minded about it and: ‘To note the difference between humour that promotes a received political or social position and humour that uses the vernacular to provoke new ways of thinking’.[13]

My fascination with second-hand bookshops led me to this book (and the MOMA one too) and hence I may be doing no favours in recommending an exhibition from over a decade ago with an out-of-print (in all possibility) catalogue, but I think for me learning has to use what it picks up, like Autolycus picks up ‘unconsidered trifles’. I’d love to hear what others think however about the general issues if you can’t find any references here that match your different experiences.

Love

Steve

[1]Sally O’Reilly (2010: 110f.) ‘Bawdy Beautiful’ in Tim, Batchelor, Cedar Lewisohn & Marin Myrone (eds) Rude Britannia: British Comic Art London, Tate Britain. Pages 110- 111.

[2] Ibid: 110

[3]ibid: 111

[4] Ibid: 111

[5] Kwock interviewed in Shana Beth Mason (2019) ‘Sex, Spunk, Shoes and Sweet Satisfaction: A Q&A with Cary Kwok’ in Frontrunner Magazine (online) available at: https://frontrunnermagazine.com/posts/sex-spunk-shoes-and-sweet-satisfaction-a-qa-with-cary-kwok/

[6] Tim, Batchelor, Cedar Lewisohn & Marin Myrone (eds) op.cit: 94

[7] Ibid: 94

[8] Kirk Varnedde and Adam Gopnik (1991: 223f.) High & Low: Modern Art / Popular Culture New York, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA).

[9] Ibid: 227

[10] Tim, Batchelor, Cedar Lewisohn & Marin Myrone (eds) op.cit: 22

[11] Ibid: 64

[12] Ibid: 137

[13] Cedar Lewisohn (2010: 13) ‘Carry on Tate’ in ibid: 12f.