This is a blog about the art of Luigi Lucioni, which some whim persuaded me to entitle: ‘The Stilled Lives of the Closet as an approach to the art of Luigi Lucioni (1900 – 1988)’. It uses the book / catalogue of an exhibition: Katie Wood Kirchoff [Ed.] (2022) Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light for Shelburne Museum, Vermont published by Rizzoli Electa, New York.

The cover of the book / exhibition catalogue for the exhibition at the Shelburne Museum, Vermont.

I discovered the art of Luigi Lucioni in an article by Cassandra Langer in The Gay and Lesbian Review. In this piece, prompted apparently by cultural heroes of the twentieth century Lincoln Kirstein and Romaine Brooks, she claims that Lucioni’s ‘allegories stepped out of the closet’. She goes on to say that examining their ‘their queer gaze’ reveals a ‘twilight vision’ that was ‘a response to the heterosexism of the times’. In the article, the argument for this is minimal though the words have a confident ring, based mainly on the artist’s networks in queer bohemian New York, with artists on the ‘PaJaMa’ group, ‘comprised of Paul Cadmus, Jared French and Margaret French as well as Lincoln Kirstein. In his circle too were artists about whom I have already written blogs: Glenway Westcott and George Platt Lynes (see links for access to blogs).[1]

This blog is an attempt to see what justification there might be for my own interpretation of Langer’s claims and is therefore hopelessly speculative and frankly subjective, but in looking at art that some people see as queer art but is not obviously so, those methods remain necessary. In particular my interest is in how the paintings might articulate a concept of a closeted sexuality, which a peculiarly interesting article in the book on which this blog is based defines, using the ideas of Jonathan Katz. In this article David Brody cites Katz’s characterisation of closeted art as giving ‘form to the play between secrecy and disclosure that is the very essence of the closet’, wherein ‘in order to qualify as the closet, a difference must somehow become visible not as silence but as a silencing, a denying, a withholding from view’.[2] However, I extend the idea of queer art being visible as such not only in the ‘coded portraits’ of queer friends but in the more frequent ‘still lifes’ and ‘landscapes’ which earned his bread and which were his major output. In doing so I take my prompt from Langer’s claim that these paintings too contain ‘homoerotic symbolism’. I take this argument however much further than Langer warrants and hence she is not to blame for my excesses.

First of all though, I think we have to forget that homoerotic content can be equated with symbols of the phallic or anus – that which Langer refers to as identified by James Saslow’s Pictures and Passions – in ‘rising towers and silos’ in Demuth, ‘rising mountain peaks’ in Hartley or the anal mounds seen in Grant Woods ‘swelling fields and rolling meadows’.[3] Such identifications are neither verifiable nor really justified as a subjective response to a mode of representation which is primarily a mimesis. Silos are things called silos before they are a phallic symbol, and would be the latter in the eyes of inflexible coders even if they had never been painted. If we are to find evidence of a sharing of the homoerotic then it will be in the treatment of these things in the design and process of visible execution of the painting itself, something that is in the painted marks, or the combination of represented objects and their difference from what is the expected, or the norm ,that seems set on disclosing the homoerotic while concealing that this is what is happening. It is the latter that is the manner identified by Katz as the sign of the closet in queer painting, as I said earlier.

We can examine examples to show what I mean but will start not with Lucioni’s Vermont or Italian landscapes, for the case with these is yet more complex, but with the paintings nearest to the concept I want at the centre of this argument, which is ‘still life’. Lucioni painted many still lifes. They are theorised by Thomas Denenberg as responses to the turn away from ‘narrative traditions in nineteenth-century art’ and ‘the kinetic embrace of the Impressionists’ to be replaced by, in Bruce Robertson’s words cited by Denenberg a “certain stillness”.[4] As I proceed in what follows, I will further develop this idea in terms of a strategy for visualising the closet of occluded sexualities by developing that concept from the relatively dead metaphor implied in the term ‘still life’ to the revived meanings in my version ‘stilled life’, which suggests that this genre is about the metamorphosis of ‘life’ in motion, sound and fleshly vibrancy into something rendered static and silent (for to be ‘stilled’ can mean both). ‘Stilled’ implies too that the silencing and immobilising is caused by an external agent, the same kinds of psychosocial agencies (heterosexism and homophobia) that created the closet. However, in order to see how we got there, it is useful to remind ourselves of what a ‘still life’ is understood to be as a genre in art. Here I cite my own earlier attempt to summarise the tradition based on a short and wonderful book by Erika Langmuir. I summarise some of what she says here in an earlier blog on Spanish still lifes.

The genre in question was variously called still life (originally from the Dutch categorisation of the mid seventeenth century) or nature morte (from the French re-categorisation in the eighteenth century). When we look at artworks, we can forget that the making of some of the pictures we name as examples of a particular category come from times well before the category was either named or described in a very specific way as independent of other art works. Moreover, some of these examples may also have been considered primarily to be something other than just a work of art, or at least not only as such. Thus Erika Langmuir shows that Roman culture developed, from Greek models known to them, categories of ‘wall painting representing fruit and other provisions’. These were interior decoration of a private villa (and sometimes self-advertisement of the inhabiting family’s supposed hospitable qualities – or an idealised version of those) known as xenia. These represented, according to Vitruvius, the riches of local grown or reared vegetable or animal produce that were made available to their foreign guests as gifts. These wall-paintings were not discrete from the homes they decorated. Discrete identity only becomes to be a requirement of art that has itself become a commodity rather than being a practice used to represent objects for another purpose. Nevertheless, xenia may pass as an origin for still-life.

Moreover, they were not alone an example of paintings in which objects were represented for different reasons. Even by 1650 when a term recognisable as a name for the independent art category, stilleven in Dutch, those other traditions of painting still ‘sullied’ any categorical purity applied to those pictures pretending to the title. Langmuir begins her short but wonderful book on Still Life by looking at the traditions that met a need to represent everyday objects in earlier painting, naming three such traditions. We have already hinted at a case for xenia that were primarily of objects and fed into later forms of still life. However, in a second strand of tradition, objects were used in several other genres for other than obvious reasons of representing reality (in mythological, history or sacred painting for instance) to represent an abstraction, sometimes named as iconic or as symbolic of a certain ethical virtue or abstract characteristic of learning about thought, emotion or sensation. These appeared in allegories or religious symbols and sometimes had coded iconographic meaning, such as lilies denoting the Virgin Mary’s chastity and purity, or social emblems, like the symbolic accoutrements of a monarch’s office. It can be argued in fact that the vanitas theme, so often attached to worldly objects, is a version of this.

A third type is the picture of ‘low’ or common life, which might also be traced to the classical origins described by Pliny the Elder as a rhyparographos (‘painter of filth’), where filth equated with ‘sordid subjects’ from the ‘baser’ (kitchens and laundry and so on) aspects of domestic life of the lower social classes. In Holland later, and in Spain with a complex multiple origin, this connected to traditions of the genre painting and narratives of a wider national social life in the picaresque novel. Jordan and Cherry, for instance, connect one instance of such painting to the term bodegón; a term singular to Spain. In an early use by Pacheco, about his son-in-law Velázquez, the word referred to a kind of ‘humble eating place’ – a tavern or beer cellar.[5]

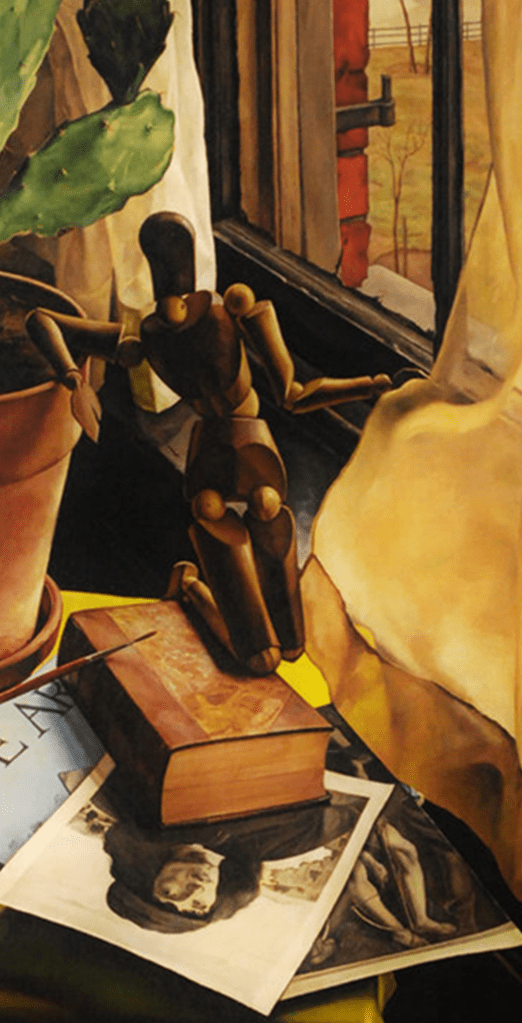

Of course there is information in excess in the above set of definitions but we will find some of it of use in looking at Lucioni’s stunning still lifes. I extend to start with a fascinating 1933 example entitled Contemporary Conversation.

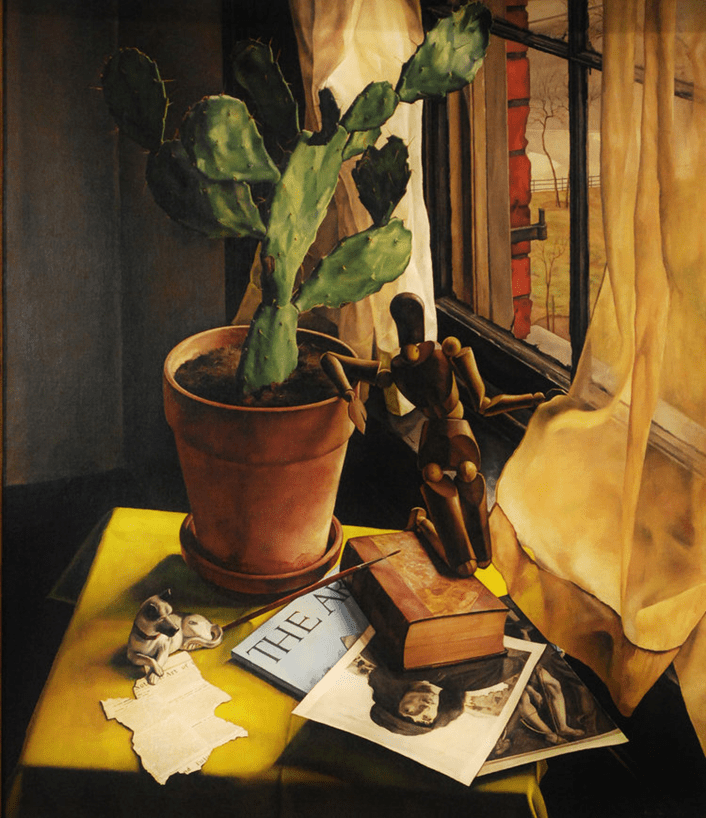

Contemporary Conversation 1933 Oil on canvas 32 x 26, Zanesville Museum of Art.

Katie Wood Kirchoff sees this painting as straining beyond ‘still life’ boundaries to offer:

… biographical insight into Lucioni’s world and doubles as a kind of self-portrait, evincing an artist who was actively and eagerly absorbing, digesting, and reformulating the modern world around him into the space of his American pictures.[6]

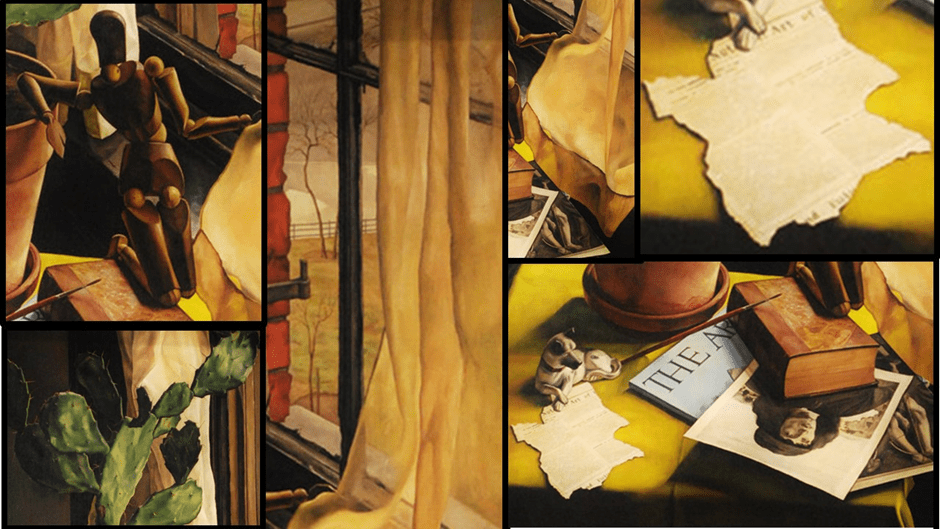

This is a satisfying insight even if we confine our understanding, as Kirchoff does, to Lucioni’s referencing of the life of the contemporary artist conversing with, and contributing to, older traditions of art and their transformations in modernity. It is worth interrogating its details though; hence my collage below:

Autobiographical codes appear in Kirchhoff’s description of the piece, most notably the ‘scrap of paper shaped like the Lombardy region of Northern Italy, Lucioni’s homeland’.[7] Yet this ‘scrap of paper appears cut from a periodical discussion of art, whose headline is barely discernible although the word ‘Art’ is clearly legible to the left of the dog figurine’s paws (the whole title might be ‘Notes on Art’). Clearly the reference links to the other icons of art which also appear in his still life painting Anachronisms (1930). These are symbolic not only of Lucioni’s background but indicate by code that this picture is a commentary on (or ‘conversation between’) art traditions represented by the journal The Arts and the black and white reproductions of Renaissance paintings. Meanwhile the painting references other traditions than those based on the human figure, represented by the iconic flexible wooden mannikin figure as well as those painting.

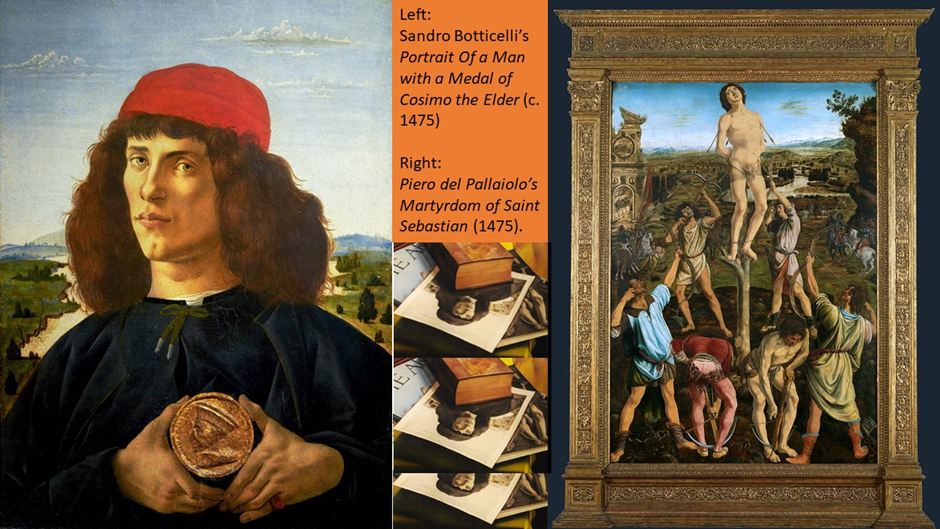

Through the window is a typical Vermont landscape exquisitely detailed where it is not veiled by gauze curtains, which was the staple of his income in the 1930s. Behind the figure, and providing an uneasy context of the prickles and hard skin which protect succulent plants, is a cactus which Kirchhoff rightly but tentatively identifies as the same that may have appeared in earlier still lifes. Still life, of course, was another option for Lucioni’s art and this too was a seller since it could so easily be opted into a concern for seeing painting as abstract design (another point made by the editors of this catalogue). However, for the moment I wish to quiz another possible significance in Lucioni choosing whether to pursue landscape, still life or, as with Cadmus, the hyper-realistic painting of the figure, especially the male figure as an option for his characteristic art. To do this lets look at the black and white reproductions which Kirchhoff identifies as Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait Of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo the Elder (c. 1475) and Piero del Pallaiolo’s Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (1475). The reproduction of these in colour are below:

Reproductions available online: https://smarthistory.org/botticelli-portrait-man-with-medal/ (Botticelli), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antonio_Pollaiuolo_003.jpg (Pollaiuolo).

Both paintings of course can be seen to represent art that uses the figure, either in portrait or symbolical or even allegorical narrative -although the relationship between those categories are of course blurred in the Renaissance in Europe. However they are also potentially icons of queer sexuality, especially the figure of Saint Sebastian, who has this resonance throughout art history up to, including and beyond Derek Jarman’s great film in Latin.[8] Botticelli’s portraits of young men have long had a queer reputation, although the historical evidence is slim, except for the surviving summary of his lost arraignment for sodomy before the Florentine Court of the Night in 1502 reads “Sandro di Botticelli si tiene un garzone“ (that is, ‘he kept a boy’).[9] As Rocke says however of this and other cases of famed Florentine artists: ‘in the broader social context of sodomy in Florence the experiences, fancied or real, of those prominent artists were probably little different from those of thousands of other, less famous men’.[10] However, icons they most certainly were and would be well known to Lucioni, as they were to his friend and fellow hyper-realist ‘queer’ painter Paul Cadmus, who chose a more defined figurative and narrative route for his art.

Where I am going with this line of thought will be obvious. The autobiographical elements about choice of focus as an artist for Lucioni must and does touch on queer coding as much as do his portraits in Paul Brody’s assessment to which I have already referred. In a sense the choice of an artist’s mannikin, almost crossed with a paint brush is iconic of this figural option. I find this metaphor of the painter’s figure deeply disturbing. Here is the figure again:

Its physical contortions are stressed ones. It’s purchase on a position in the world is literally tentative. Only one knee of the articulated figure’s left ‘leg’ assists it to hold on at its base, elevated as it is above the book on which it surely cannot securely ‘rest’, although the foot of that ‘leg’ hooks over the book edge as if attempting a locked position. The other leg hangs in air. The weight of that leg would cause it to topple were it not that the figure is meant to lean on the cactus’ plant pot with a hand hanging loose from the plant pot edge. Moreover the right hand’s is placed in such a way that it appears to be grasping the yellow gauze curtain at the window for support, although clearly such an interaction must be staged by the scene designer. The anthropomorphic feel here is, in my view of it, an indication of motion ‘stilled’, such that it avoids the precarious subjection to time and motion that might result in a fall, the consequence of imbalance.

Moreover, I find the head of the figure disturbing too to my eye, for though its body appears to face towards the viewer the head seems to face so that its imagined gaze looks out behind it and to the left to the Vermont landscape (I have a sense of the head turned in a 360 degree angle from its unstressed and natural resting position, looking anywhere but to the spiky symbol of protected succulence on one side or down to the gay male artistic icons beneath him). This is not a man at rest, or if so, only because the hyper-realism of this kind of art actively stills time and motion, renders history nugatory and inarticulate. In my view this is the very symbol of the closet – a man pretends his interests in the public world conceal his tense desires and needs, whilst making them semi-evident and disclosed to a public, if the codes can be correctly read.

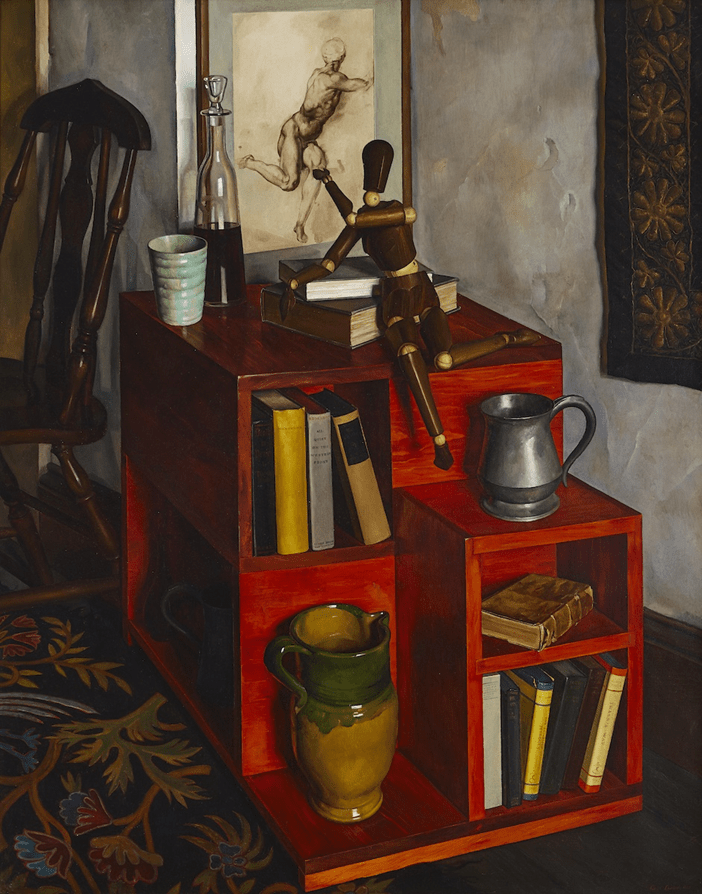

About what are these ‘contemporary conversations’ then in this painting: I would guess they are Luigi Lucioni’s attempt to bridge Lombardy and Vermont, his past and present, the art traditions of the Renaissance with their frank appreciation of male beauty clothed or unclothed and the retreat of modern art to landscape and still life, faithfulness (this the dog suggests) to one’s private and interior queer desires and emotions or looking out to a world that silences such emotions, at least to the degree that it can actively fail to recognise them if it wishes. This is why this is a painting about ‘time’ but placed in stillness by its circumstances: many of its ‘contemporary’ conversations, those at least that represent gay love and desire are silenced. By an interior that becomes increasingly to look like a closet. In my view, this is what links it to Anachronisms, where the mannikin appears again, aspiring to the beauty of a male nude in art as if he were clambering up to it against presented (and very present) difficulties, but it is a nude positioned in the past not current history of art for Luigi. Again the climber’s position is unstable unless time stands where it is, barely supported by books and artistic aspiration.

Anachronisms (1930) 40 x 30 in. Private collection. Available at: https://shelburnemuseum.org/online-exhibitions/luigi-lucioni-modern-light/

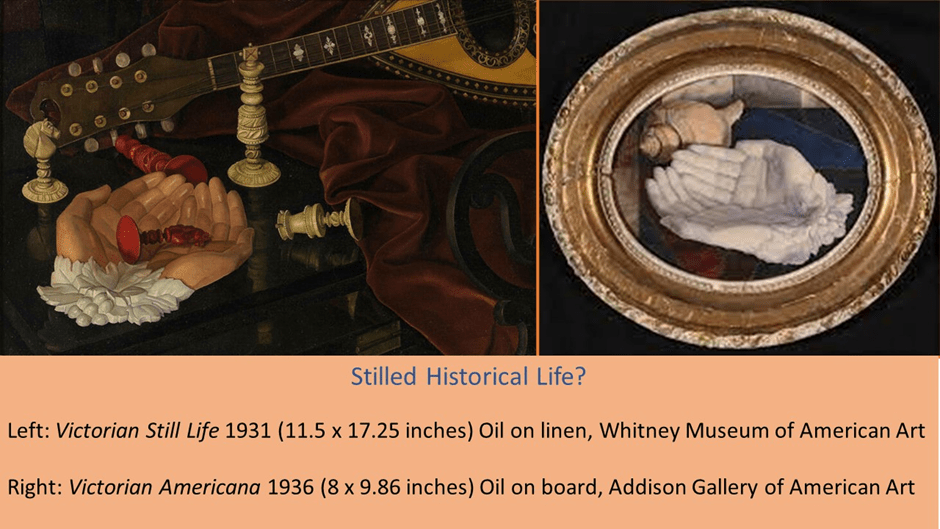

Of course, it is easier to make this case where the painting invites anachronistic narrative to some viewers such as the modern art establishment, even its radicals such as Clement Greenberg, were trying to shut down, and which again, as a consequence, would silence queerness, which depends on the instabilities of temporality and onward self and other discovery. Does it explain other still lifes where the human figure, gesture or autobiographical is less obviously pertinent, even as symbols. Given the exclusions mentioned here I exclude a still life like Heirlooms of 1933, with its obvious reference from object to stories about the familial past. Likewise we need to exclude paintings that shout out in silence like Victorian Americana (1936) and Victorian Still Life 1931 where the story from the past is about (in a very indirect way since the meaning only enters because it belongs, as it were, to the antique object contained in the still life) some gesture of giving or submission, whose narrative context has been lost. However, it is important to recognize that the transformation of items charged with family or cultural-historical meaning still have their stories fully silenced or stilled into something that seems a piece of retrieved archaism from a past that was loud with stories, of love and gestural giving between persons. It is as if the time of history as been stilled in the sense of being silenced. Whilst, I do not intend to argue this in any detail, it is worthwhile to see copies of at least the last two pieces.

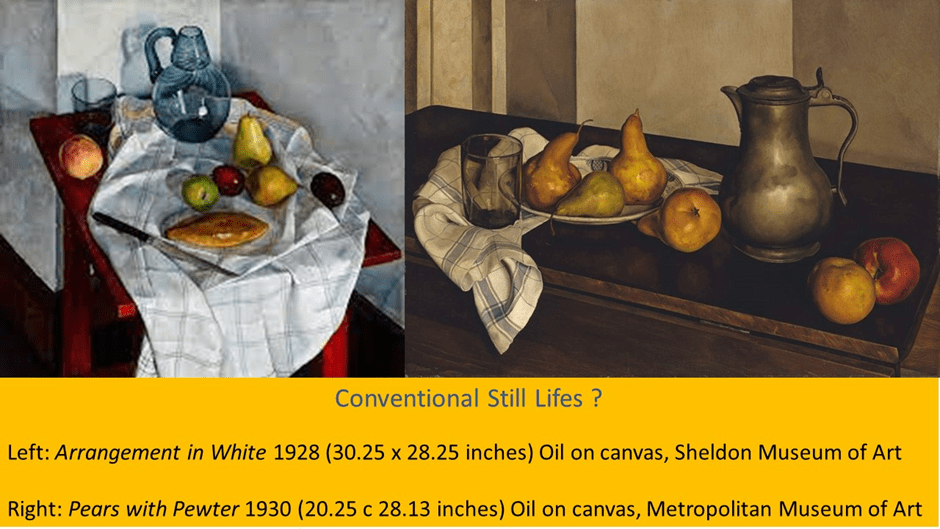

But I still keep putting off, don’t I, looking at Luciano’s more conventional still lifes, perhaps because of the conceptual difficulties with which the two pieces I have chosen have deliberately set me. For these still lives bear the marks of tradition of still lifes with the only exception being that their style of appearance was theorised as peculiarly modern, with a kind of hyper-realism that some called Precisionism. This method demanded truth to imagined sight, whether of object, or reflected or refracted light through glass like European Modernism, but eschewed the obsession with ‘bright colours and sharp angle of approach’, according to Kirchhoff. Instead this was a style imbued with a simpler ‘subdued palette and less precarious perspective’ which looked back to American nineteenth century traditions.

Thus Arrangement in White implies an Impressionist or Post-Impressionist mode of still life with a stress on the unnoticed beauty of everyday life. It recalls Cezanne to me, not least because its title plays with the kinds of geometric arrangement of design it was known that Cézanne favoured in the still life and which theorise Post-impressionist painting with its trend to abstraction. In Pears and Pewter, there is archaism of course, in the antique homely vessels, especially the dented pewter but no item is presented as an heirloom, as in the obvious stilled histories above them in this blog. Katie Wood Kirchhoff sees in this painting a tension between the ‘grounded’ and earthy in the fruit and pewter, contrasted with the glossy top of the dropleaf table, as if an American ‘finish’ (equated with the cool precision of seeing objects refracted through single and double thicknesses of transparent glass as precisely as possible) were contrasted with the ‘sweet treats and treasured antiques’ of a European past that the USA felt it was in the process of marginalising into un-storied objets d’art.[11]

But how can I claim a queer theme from that kind of tension. I think I can because Lucioni himself tied his description of his art as “super realism” to a distrust of the emotional baggage of an old world. Denenberg cites Lincoln Kirstein, Lucioni’s great friend and member of the Cadmus queer circle, who linked this distrust to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement in Europe, but which in its American form became, in Kirstein’s words, an ‘ironic posture of detachment, … a critical distance’ which the group termed being “cool”. Kirstein says:

“They have the dubious distinction of being known as the Frigidaire School. …. The chill of exact delineation is not necessarily harsh. There is often a tenderness of the surgeon’s capable hand, an icy affection acquired from a complete knowledge of the subject”[12]

This complete knowledge of the subject applied to the enforced detachment of the queer circle around Lucioni helped equate them with ‘painters who stood apart from the conventional wisdom of an era’.[13] Although Denenberg does not do this, I would equate that detachment with the displacement caused by inhabiting the closet, where what one wants to say about a suppressed truth has been silenced by convention, and how one wants to act being rendered immobile too by the same forces and their agents. I agree this is tenuous but queer vision easily elides with an interest in the dream not the reality, the shadow that reveals light (which is the ONLY way we see light in Pewter and Pears) mor important than the supposed ‘lives’ illuminated only by inflexible norms and emotional stances.

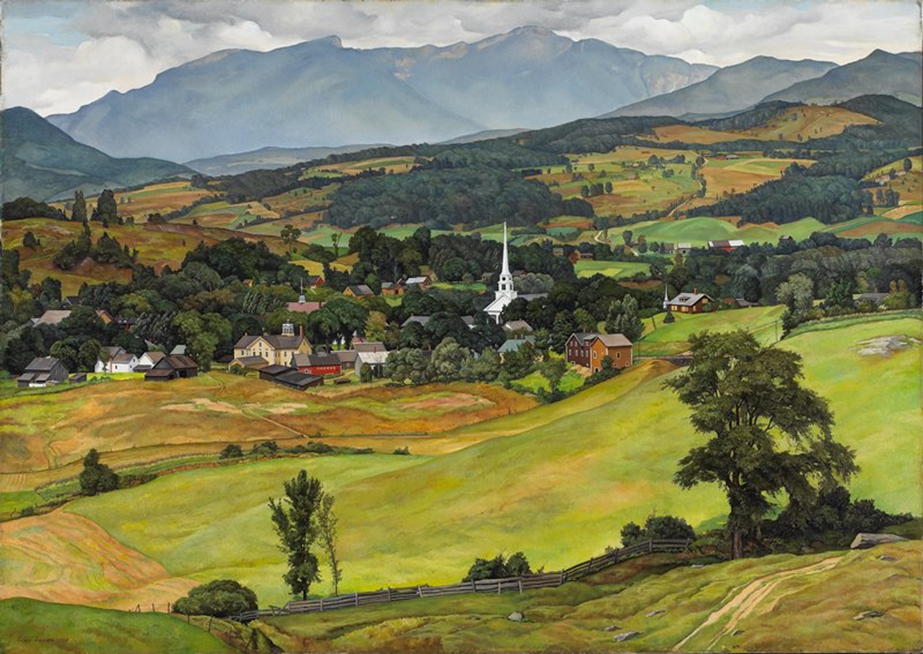

It may be even more concerning that I see this in landscapes, even the least obviously queer. According to Richard Saunders, Village of Stowe (1931) represents the kind of painting Lucioni could sell (he realised $1,000 for it which could have paid his New York studio rent for two years) . For this reason he says, it is an example of the kind of myth of an ordered American landscape rich patrons wanted to own and be associated with.: ‘a pastoral haven from the complexities of modern, twentieth-century life’.[14]

Village of Stowe, Vermont (1931) Oil on canvas.

A brief look at the picture such as I have offered in small reproduction might seem to confirm what Saunders says but Alexander Nemerov sees a myth in that painting motivated by complex emotional energy and resistances that balances homesickness with the desire to overpass, the eye travelling beyond the archaic lifeless village to an unseen place equated with the rising peaks of Mount Mansfield and the clouds above. Of course I add to Nemerov’s meaning here my own queer perspective.[15] Nemerov’s beautiful reading relies on the depopulated and empty feel of a village that seems located entirely in the past, and shows that replacing a bounded homesickness might be a love of a restless landscape. He speaks of the town portrayed as denuded of a vibrant religion and showing nothing but a whited spire ‘once occupied by angels and gods’ but no longer: ‘resistant to historical change. Lucioni’s Stowe looks like a nineteenth-century village, with no automobiles, no gas stations’. Around that sterile town and beyond it, on the other hand ‘the land is restlessly on the move, as if subject to the plate tectonics underlying art itself. Landscape has moved up, taking center (sic.) stage’.[16]

The desire is for land that does not necessitate old norms and conventions but offers a new freedom such as that sought by Whitman; where distance, untouchability, unreality is the object of desire (and what could be more queer than that). Nemerov looks at the structure of space with its ineffective barrier fences merely feeding the ‘forward movement’ of the eye and desire, but I see more than these desiccated barriers to movement of the eye into a Stowe absent of even signs of living people (even the school on the viewer’s left is empty). There are layers of land in the painting between which are absent falls of land leading to a kind of pit in which the village sits before the eye is drawn by disappearing paths (the ones in front of the village lead nowhere) to overlook it and move on upwards out of the temporary dip it offered him. The eye moves onwards towards something Nemerov calls ‘ distance’: ‘its feeling of being perpetually unreachable and yet desirable’. Nemerov, however, slips out of the logic of his own argument by equating the village itself with distance, but in my view the village has its back to the viewer, the fronts of the houses and buildings we see the backs of look beyond, and inevitably up, to something outside its normative look and are approached through scrappy wilderness and possible marsh. It isn’t a ‘ fantasy village of fairy tales’ as Nemerov says it is but more like what the Apostle Matthew meant by a whited sepulchre, locked in its own ‘goodness’, but with no progressive love.

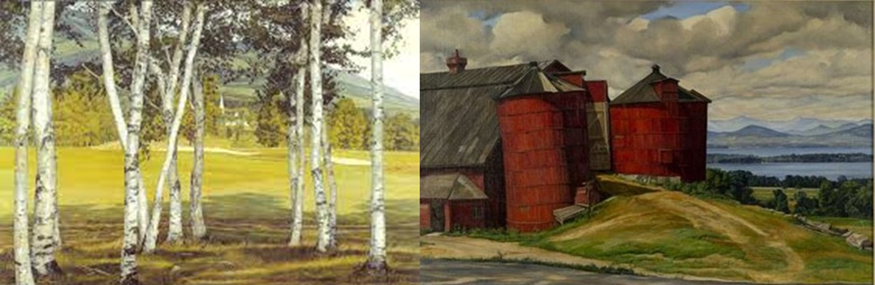

The same could be said of other landscapes where old and abandoned places of human activity and story appear to be falling and desiccating (or whitewashed). Even their red blood-coloured tottering phallic silos totter unstably. Living trees however have the suppleness of bodies in dangerous contiguity. You need to look at more of them than the following which I do not name but use as typical for I need to get to the end by return to Brody’s argument about the queer coding of portraits.

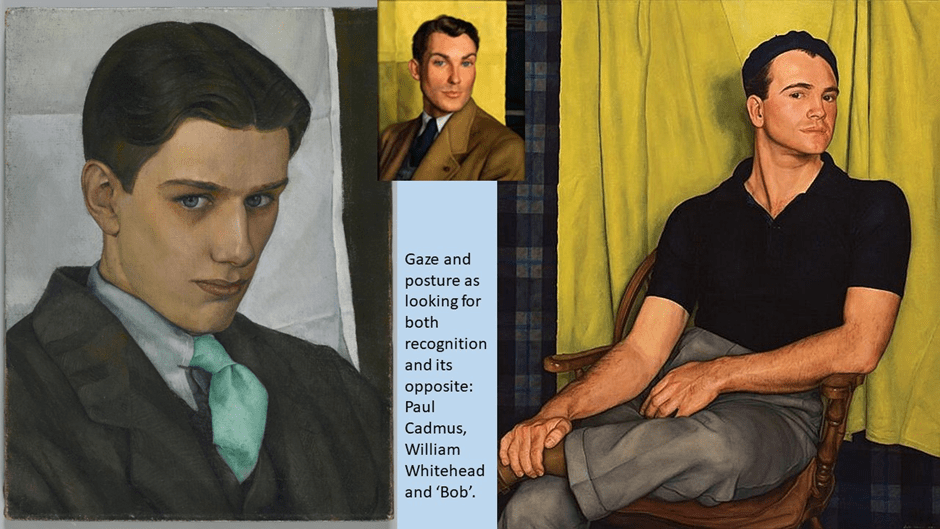

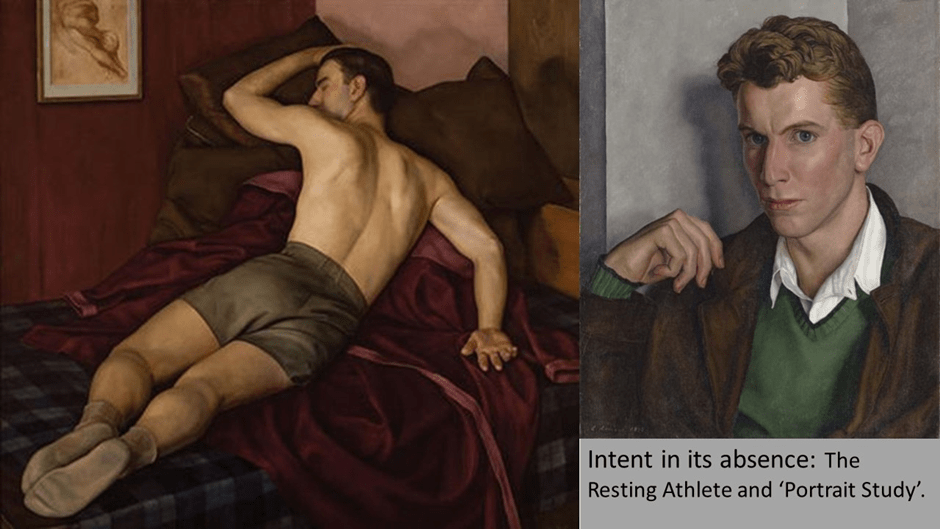

Brody argues that, unlike Paul Cadmus, the closet is apparent in these portraits in their refusal of openness to allowing a viewer not already in the know to do other than ‘disavow any overt sexuality’ in them.[17] Yet this is to pretend that sexuality always takes the raucous form of Cadmus’s The Fleet’s In. Brody’s analysis of the queer circle of Lucioni as they appear in portraits is in fact an acknowledgement that sex may be more apparent in an indirection in direct gaze, which makes the process of mutual recognition itself sexual, even when not a matter of overt sexual body parts or nudity. How one holds one’s own body and the torsion and tension of body become sexual, especially the body caught in sleep and facing away from us (but not forever, as in Resting Athlete (Amateur Resting of 1938). May I just leave you with inadequately reproduced (by me not the catalogue) examples.

You will love Luigi Lucioni and the whole book is better than just admiring the David Brody essay as Langer does in my opening paragraphs. But you have to bring your OWN queer perspective to the other bits. And why not? Lol.

Love

Steve

[1] Cassandra Langer (2022) ‘Portraits with an Electric Charge’ in Gay & Lesbian Review Vol. XXIX, No. 6 [Nov. – Dec. 2022), 47f.

[2] Katz cited by David Brody (2022: 69) ‘Coded Portraits: Lucioni’s Queer Circle’ in Katie Wood Kirchhoff (Ed.) Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light for Shelburne Museum, Vermont published by Rizzoli Electa, New York,64 – 89.

[3] Cassandra Langer op.cit: 48

[4] Thomas Denenberg (2022: 30) ‘Stillness, Light and Magic’ in Katie Wood Kirchhoff (Ed.) op.cit: 20 – 37.

[5] From my blog on Spanish still lifes at Bishop Auckland. Available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/04/03/early-spanish-still-lifes-can-be-interpreted-as-promoting-the-value-of-a-framing-space-in-which-to-place-singular-objects-however-later-examples-emphasise-in-antonio-arellano/

[6] Katie Wood Kirchhoff (2022: 62) ‘Contemporary Conversations’ in Katie Wood Kirchhoff (Ed.) op.cit: 38 – 63.

[7] Ibid: 62

[8] The arguments with examples are well set out in the Art UK dedicated webpage by Flora Doble and entitled: ‘Saint Sebastian as a gay icon’. See https://artuk.org/discover/stories/saint-sebastian-as-a-gay-icon

[9] Cited Michael Rocke (1996: 298, note 121) Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence’. For my blog on this book follow this link.

[10] Ibid: 139

[11] See Katie Wood Kirchhoff op.cit: 56f.

[12] Cited Thomas Denenberg op. cit: 31

[13] Ibid: 31

[14] Richard Saunders (2022: & 119) ‘Luigi Lucioni’s Vermont’ in Katie Wood Kirchhoff (Ed.) op.cit: 108 – 131

[15] For Nemerov on his own on this see Alexander Nemerov (2033: 93, 103f.) ‘The Love Song of Near and Far’ in Katie Wood Kirchhoff (Ed.) op.cit: 90 – 107

[16] Ibid: 93

[17] David Brody op.cit: 68