‘So, I’m here with my mum to ask a few questions about life’.[1] ‘… – yes, she will continue to fashion herself to help give her bodam * grace – the obstacle of items will slow down this impedance’s pace’. [2] This blog examines how and why we need stories wherein everyone, even the story, has ‘lost the plot’! It concerns Derek Owusu (2022) Losing The Plot London, Edinburgh, Canongate.

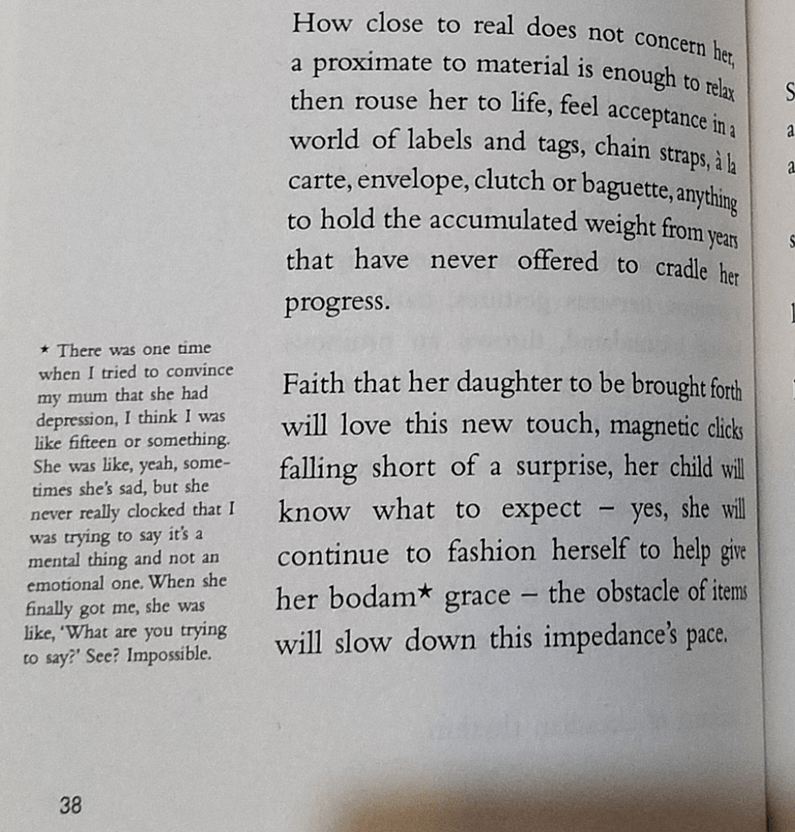

[* There was one time when I tried to convince my mum that she had depression, I think I was like fifteen or something. She was like, yeah, sometimes she’s sad, but she never really clocked that I was trying to say it’s a mental thing and not an emotional one. When she finally got me, she was like, ‘What are you trying to say?’ See? Impossible.][3]

Book cover

Perhaps unforgivably in a blog, this one starts with a long digression about why I chose this approach to discuss a novel that could and will stand by its own merits alone. My only excuse is that my blogs are shamelessly about my own learning processes. When I started this blog in fact, I intended it to follow the lead of the critiques I had read thus far (only two I must admit). Underneath some good perceptions about what we learn about Derek Owusu’s mother’s life, both reviews I read focused on the question opening Percy Zyomuya’s review in The Guardian: ‘If you were to write a history of your mother, who had left her ancestral home in Kumasi, Ghana, for London, the heartland of the old empire, how might you do it?’[4] Rabeea Saleem in The Irish Times makes the same point – that this is ‘a history’ of a writer’s mother – more forcefully and with some attempt to face the most startling of the narrative means used in the book:

The narrative structure is elastic and malleable in Owusu’s skilled hands as he navigates and positions himself quite literally on the margins, while giving centre stage to his mother’s story.[5]

Both reviewer’s admire Owusu immensely but neither really interrogate the nuance of the book, either in its representation of mother and son relationships or their exploration of a shared mental space, one that has touched on issues of mental health. It was re-reading these reviews (see footnotes for links) and then the novel again that I felt my current dissatisfaction with the bland approach I had taken to the book based on a first reading. For my own sake, I am preserving that first draft title here as it appeared in a tweet just to show how inviting it is, at first, just to run away with the fact that telling your own mother’s life-story fascinates and seems the fundamental issue in such a book:

Moving from this position came from a re-reading of the novel, as I have suggested, and particularly in taking notes to slow that reading, and to puzzle over some of the issues I had had as an entitled white reader, ready to brush over the local colour of the novel (I hope I didn’t think in these clichés but I may have done since white inheritance will out however hard we try to disguise it). By local colour I mean an issue again mentioned in both reviews, and surprisingly enough a similar ‘colour’ metaphor is used by Zyomuya to describe it:

Instead, the extra colour the narrator wants is found through painstaking observation and a poetic imagination as the novel code-switches between a poetic voice and, in the footnotes, its demotic counterpart, also interpreting across English and the mother’s tongue, Twi.[6]

Zyomuya describes himself as a Zimbabwean writer and hence, given his cultural life was formed in Johannesburg, South Africa, we do not expect him to feel any more Ghanaian than I do, but clearly the existence of Twi vocabulary is not seen as integral. This is so too in Saleema’s Irish Times review, who says:

The story is written in English, occasionally interspersed with untranslated Twi words which are then followed with footnotes in the margin written from Owusu’s reflections on his mother.

Saleema has seen this method before she tells us: ‘In Exquisite Cadavers, Meena Kandasamy employed this technique to add dimension to her dual narrative’. Furthermore Saleema infers that Owusu has a similar reason for this method: ‘to deepen our understanding of the dynamics shared by the mother and son, …’.

My second reading of the novel suggested to me that Owusu wanted more than to localise the sociocultural origins of a migration story or to add dimension to the issues that might underlie a son’s story of his mother in this context with different views of language. Indeed both accounts are imprecise since the different between the centrally spaced large text of the novel and the marginal notes in much smaller text has much more to do with the kind of differences that each version of English tells us about the experience of acculturation.

I discovered this by pondering on a particular example. Below is a photograph of the page to show how the textual paths in this one novel are differentiated in graphic as well as literary style. It is a problem that I encountered in trying to cite this piece for my title (see above) for the blog.

And this is particularly rich in the handling of issues of mental health, which has before absorbed my interest in this innovative writer. Indeed, I have addressed that topic in two previous blogs: the first dealing with his debut novel can be found at this link, and the second including material on his essays here. With this novel I got to this interest because I had pondered long and hard on the term ‘bodam’ and its relationship to the marginal note which summarised in the ‘demotic’ style mentioned by Zyomuya the discussions between mother and son on ‘mental health’ and / or the ‘labels and tags’ it receives in each of their worlds. [7] Understanding how and why this note is placed in relation to the word ‘bodam’ is not made easy by Owusu and readers without a knowledge of dialects of Ghanaian languages will, as I was, be at a loss.

In fact the word ‘bodam’, I was to find, indicated (in Southern Ghana at least) identification of issues of ‘mental ill-health’, although my source claims this is the word in Fanti, a possible, but contested, alternative dialect of Twi, which the characters of this novel claim to speak. My source, found by searching the word ‘bodam’ on the internet, was in fact an interesting academic research article in social psychiatry dealing with attitudes to mental health in Ghana, which contains the following:

Participants who had difficulty understanding English constituted a small minority (<10%). For them the native trilingual interviewer (S.N.) translated the questions into Twi or Fanti as required. The central term “mental illness” was translated as “Abodam” (Twi) and “Bodam” (Fanti). Both terms have the same scope as the English term “mental illness”.[8]

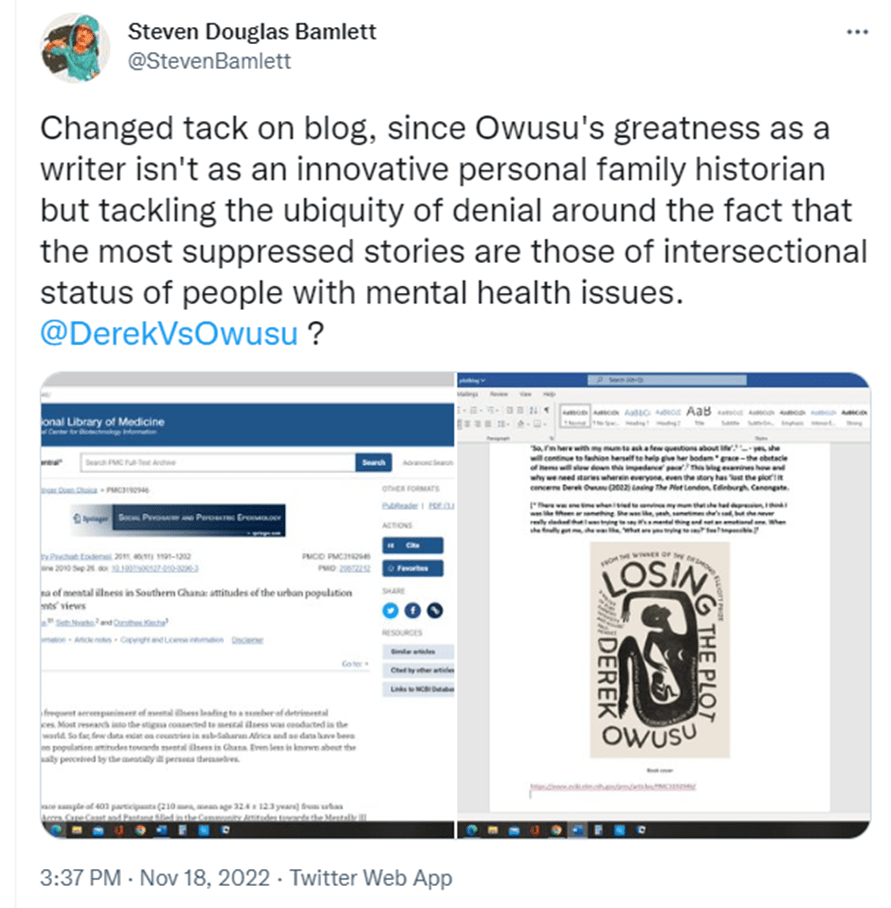

Hence the change of tack of this blog, which being me, I again announced on Twitter in the tweet reproduced below.

But even having a ‘translation’ of the term ‘bodam’, one we could only infer from, but which is coherent with, the marginal note, we are still left with the issue of how we read such material. It is this question that fascinates me. So here this central issue again:

‘… – yes, she will continue to fashion herself to help give her bodam * grace – the obstacle of items will slow down this impedance’s pace’.[9]

[* There was one time when I tried to convince my mum that she had depression, I think I was like fifteen or something. She was like, yeah, sometimes she’s sad, but she never really clocked that I was trying to say it’s a mental thing and not an emotional one. When she finally got me, she was like, ‘What are you trying to say?’ See? Impossible.][10]

Obviously seeing the note and central text together with no obvious subordination of the note to the text (such as appearance in a margin and a smaller font that is more difficult to read and thus suggests that there may be reason not to need what it offers) makes the contrast more obviously about the register of the language both in their lexis and syntax. The note is indeed demotic, using popular but informal vocabulary, exclamation and phraseology from oral language like ’I was like’, ‘clocked’ ‘She was like, yeah’ to introduce reported speech, ‘it’s a mental thing’, ‘she finally got me’, and so on. In contrast, though the central text uses Twi (or Fanti) words, it has a literary structure and rhythm (perhaps even metre), with, in this case, even a rhyme (between ‘grace’ and ‘pace’) that lends even more elegance to its delivery, one that is, at least, a prose poem. The lexical choices open themselves to a poetic archaism – in phraseology too – and to a consequent sense of precise but fussy ‘grace’, where meaning struggles to be raised from obscurity, such as that that might arise from using the term impedance. It feels like a usage we expect in a seventeenth century Metaphysical poet though it uses a modern context, that of the measure of electricity to convey the counter-intuitive idea of the pace of a resistance.

In the mean-time the content of these voices is about how we tell the story of bearing the mental drag of ‘accumulated weight from years’, and not just the story of one’s mother, though it is also that. It is the story of how historical and contemporary structural oppression is borne by the person who has, with or without knowing, introjected it. If the marginal voice is the son’s voice, it is a voice we cannot read without irony for it does not do other than translate the terms which the woman who tries to wear her internalised oppressions (her bodam) with some pride, unconscious of doing so, into the terms of Western psychiatry. Would it be better if she, as the marginal voice does, translated such bodam into the ‘fact’ that ‘she had depression’, as her adolescent son thought she should. This from a son who distinguishes mental states from each by words like depression, assuming a precision to them: ‘He is not depressed but flat, …’. He may feel blocked into a corner by her resistance to this explanation, that she is ‘depressed’, and its corollary that she accept appropriate help from modern services (and perhaps the iatrogenic consequences) but she may be simply right to ask him: “What are you trying to say?”.

For if about something, the themes of translation and language that run throughout this book in its mode of delivery and content is about ‘trying to say’ what cannot be said in conventional terms and in conventional language (lexis and syntax) whether the convention be that of a modern technically infused language or the ‘hip’ of the street, each with its own potentially limited ranges of reference. As ‘translations’ the notes are, and can only be partial. It is easy for a reader to miss even what they addressing in the word or phrase to which they are attached, because the notes always turn into the son translating in a way that the phrase is contextualised in a meaning that focuses on his experience rather than hers, of if hers, on the consequences of it to him. [11] There is a veiled warning about him in an appended note about translations from Twi: ‘These translations are approximations and a lot of their meaning and changing connotations may be lost’.[12]

Indeed this is not only about translations from Twi to English for there are similar approximations in the ‘translation of the central formal literary text applied to the mother to the marginal notes, in ‘demotic’ and apparently spoken by the son. And this is at the heart of the passage we are looking at because the son is responding, often in correction of her terms (bodam to depression for instance) because he is reacting with strange resistance to her attempt as subject of the formal text to ‘continue to fashion herself to give her bodam grace’. Although this speaks on its surface about her choice of apparel, it inevitably in such a knowing literary text invokes the notion of ‘self-fashioning’, that concept used to explain the function of literature in contributing personal agency to the way one is seen and perceived by others, in this case readers in literature (and visual art) from the Renaissance onwards by Stephen Greenblatt, but now widely referred to without reference to him. It is a concept useful when we see how selves get ‘read’ through documents, even in obviously erroneous ways. For instance as she lands in Britain, ‘new documents will read her younger than every sibling’ though at home she was the eldest daughter. [13]. Throughout an issue in this novel is, who has the right to ‘fashion’ (that is, to construct and embellish) this woman’s life.

Of course translation always is about how, sometime,s the same basic sense is conveyed with differences, even when only the context of the speech or writing act changes. There is a tremendously moving passage in which the term ‘passage’ itself refers to a passage of text or speech and the passing of years in the instance of even familial relationships and of the ‘passage’ which is the journey of the migrant to a distance from their roots and how such passages affects the meaning of the words and language structures we use so that we lose sense of them, ‘lose the plot’, in terms we will look at more closely below. Of course most readers will recognize that these words also describe their experience of many passages in this book in their passage from the authorial experience, to say nothing of the characters’ experience, to their own readerly one in a comfortable armchair perhaps. For those who seek some kind of salvation in reading, like myself, the reference to redemption at ‘the end’ is more precise than it might otherwise seem.

We often fail to count the years when a passage loses meaning, we glide our eyes over it knowing there is nothing to redeem the end.[14]

This passage, in part,refers to how meaning passes through metamorphosis between experience of it in English and Ghanaian culture comparatively. Note, for instance, how the word ‘obroni’ in particular causes problems, for though it distinguishes a white man from a Black man, it is not meant, in Ghana at least to suggest negative connotation, though in England it acquires that meaning (of wicked man) for badly treated migrants (badly treated by white people with power). That bad treatment often rests on the translation of the meaning of even silent action (like looking at someone) between white men and Black women.

… the obronis sitting in the next aisle of broken seats may assume she’s inviting them over, those twisting and polishing her tongue, blowing grammar without savouring the sound, a switched tempo, contorted into another language.[15]

In that partial sentence, contorted by its sense as well as the burden of its context of how we experience sitting in a crowded space aware of others’ eyes and their possible intentions with regard to us, language itself becomes visceral. Exchanges in talk feel like an unwanted abrasion of physical tongues not spoken languages, grammar and sound get felt in the passage of wind from the mouth and as a taste to ‘savour’ or not. Languages go into such translations, even in terms of the body, many times in this novel. And this is part is why I think mental health is so central to this book and the subjectivity of those labelled ‘mentally ill’ informs it throughout and insists on the intersubjective difference in discourse of black oppression and the direct experience of mental ill-being (or whatever we choose to call it). I think this is so, even at the level of the novel’s consciousness about itself as a form.

Literature too is described by the conventions of a meta-language. In the theory of the novel these are those of discourses of ‘plot’ and ‘character’, with their bias towards what can be understood in linear terms for one or rounded-off and bounded ones for the other. Is this not why this novel is called ‘Losing the Plot’ (a term commonly used to describe mental derangement and confusion). The very premise of the book is that though it is organised in a sequence, with flashbacks for it starts in media res with ‘Landing’, of a airplane flight, it bears some pacy impedance from a sense of being lost and directionless, which airplane flights do not intend to be. Being lost and directionless may be at the very heart of a lone migrant’s experience however, although strangely enough the small girl in the opening is the only one with some (illusory) sense of direction: those indeed are the painful nuances of the novel’s beautiful and painful opening, with its wonderfully crafted sentences breaking the very syntactic and lexical conventions on which they also depend in order to be read.

The plane breaks through grey squalls, directionless to all but the small girl feeling the craft balance before it blooms through moist shrooms leaving a country in its second childhood for another promising the same to her, the girl, whose head is shaven by the attention of fingers like soldiers instructed to dictate how low’.[16]

This is as beautiful as it is disordered, almost as a psychedelic effect of shrooms, commonly the street name for psychedelic mushrooms which are even precisely named for dosage for degree of effect has to be calibrated in terms of whether the shrooms are wet (fresh) or dried. The prose is carefully weighed (as balanced as a craft before it blooms) so that we know these shrooms could come from the country of origin and therefore be fresh and whose indicator of that quality is beautifully assonantal in the sentence in which it sits. For the phrasing forms a perfect little embedded rhyming couplet with an irregular metre: ‘before it blooms / through moist shrooms’. The literary art continually disorders in the very process of achieving order, sense and direction, and mimes the consciousness to of a ‘small child’ unaware yet that what is ‘promised’ to the optimism of her youth will be smashed away for all cultures (that of her origin and destination). Indeed both cultures seem demented in their own specific way, in their ‘second childhood’.

That ‘small girl’ in her one and only, thus far, childhood, breaks from the subordination to the structure of the sentence in which she appears to become its elaborated later focus. Sentences which shift focus like this are almost cinematic, as if a camera were homing in from the vision of the plane to the girl amongst passengers and thence to her in close up. And the manner of the description is solidly resonant of the oppressions of her past, the soldiers instructed from above are a metaphor for the fingers which shaved her head with attention but not care. They suggested to me a background of vulnerability to politics organised in part through the random acts of violence and attempted coercion and the counter-reaction of a state aiming to look more stable than it is. Such contexts generate interestingly politically-sensitive metaphors. Though I sensed such a generative context for metaphor from the subjective feel of this sentence alone, I later read that Emmanuel Graham and Henry Hagan, in a research article, in 2021 have shown vulnerability in citizens to be an underlying, if masked reality of Ghanaian political life even today (their conclusions are summarised in the footnote).[17] Of couirse when this mother left Ghana it may not yet have become a ‘democracy’. In a novel, let me repeat, it is likely that such insights would be translated in the consciousness of a small girl to the actions of her frightened carers in the delivery of the minutiae of her care and security, such as would appear perhaps in memory of the care of her hair. In the next sentence, she ‘reaches up and rubs a hand over what survived at the roots, unnerved in her home town to curl around the toll and contrast of time, …’.[18] It is clear here that ‘fingers like soldiers’ can for a girl symbolise disruptions at other ‘roots’ than the roots of her hair – her roots for instance in hometown Ghana.

Moreover the feelings and thoughts of this small girl are focused around ‘fingers’ (although this time her own apparently autonomous ones). Later too, as roots begin to be re-established but this time in an England not yet apparently hostile: ‘She could free her fingers through what now grew from her roots – though stunted – …’.[19] However, also in England, alien fingers, though not necessarily white ones, rob the girl as she becomes woman of her autonomy hinted at in the ‘free’ play of her fingers around the exploration of her roots in our last example. She becomes sexualised by over-eager men ready to play on the vulnerability caused by hunger: a man offers her home-style food so that she ‘takes him inside’ (the ambiguity is in the text) though she had already danced on his fingertips’ (my italics).[20] In another example where oppression comes from the form of an apparently liberating religious experience of salvation, some of the most impressive verse in the novel is found in which one gags at the surreptitious movement of an intruding ‘little finger’, which also caresses her scalp:

His palm slides, presses the centre of her scalp,

Thumb and a little finger able to stroke her temple

As he prays for deliverance,

nkwan * staining her personal sermon,

Every word taking her back to repulsion.[21]

The deliverance here is for some event in this woman’s past whose exact nature is hard to read in the preceding text because deflected by its consequences in feeling and sensation but which still engenders repulsion. Her imagined ‘repulsion’ mixes into a reader’s repulsion at that thumb and fingers and the present repulsion they cause in recalling those earlier feelings of a similar kind for the woman herself. It’s so ‘personal’ and multi-focused. For instance there is beauty in seeing the consciousness of the woman of the fact that soup she has made (nkwan) has stained her clothes, just as the deliverance attempts to remove moral stain.

One of the most interesting of the son’s marginal comments is attached to this word nkwan, which only makes it known that he is referencing the word soup because he uses his mother’s nkwan as a symbol of her love for him, if love for him she had, based in the distribution of ‘ties left in the soup’ for his own consumption rather than his father’s. His extra ‘ties’ are embedded in the fufu which are served with such soups and stews in Ghana. (I think Saleema in The Irish Times is possibly mistaken to think fufu a soup per se) It is so rich this note, and is cited in all the reviews I read because an apparent note on the name of a Ghanaian soup or stew is suddenly translated into the son’s reflections (as if, in the end, for a son, his mother’s story is ‘all about me’) into the comment: ‘Listen, with Ghanaians, it’s impossible to tell when they love you’.[22]

This is achingly beautiful but also painful. For the non-intersectional in their thought, the history of black oppression may supersede other oppressions, such as those of women, the aged, the differently-abled, the ‘mad’, and queer people. But in fact, though these are not distinct categories they involve translations even in full knowledge that they can relate to modify oppressions or change their nature in their admixtures. That his mother remains a mystery to this partial commentator because she is less articulate, or conventionally literate at least, and depends on oral traditions in language, that her age removes him from her is the cause of him never knowing whether she understands his depressions or ‘relates at all. It is always a question whether there is any stable relationship. In the following the son is commenting on the mother’s half-knowing question to the son about his musical tastes: ‘Kwesi, eh yɛ hwan*? P. Diddy? / … / You think I don’t know things I know’ (italics in original).[23] Believe me this needed much translation for me. The question in Twi I eventually decided must be ‘Who is this?’. But I did not know either that P. Diddy is an alternative name for the artist white people more commonly know as ‘Puff Daddy’ and who is actually named Sean Coombs offstage. But she is challenging not only us but her son, Kwesi, about whether he respects the fact she knows things too. Kwesi’s marginal comment suggests he does not, or not confidently. There are no certainties in the note on this question:

Just so she could relate to me, or seem like she was down (she was always down to be honest, very calm, but calm people never see that they’re calm – and that’s what makes them more calm,), my mum always tried to remember the names of celebrities.[24]

Mum is an unknown to Kwesi and one he fails perhaps to always respect in a fully unnuanced way (but perhaps we are all like this with our elders). In his ‘factless interview’, he seems to continually fail to understand the reasons for her reticence and resistance (or ‘impedance’). To my ear, he seems to patronise (with a great frequency of the form ‘*Laughs*’ in the text. Her furniture – the ‘‘authentic’ leather sofa without the plastic’ (I remember the removal of the plastic on my own family’s furniture) as he does her inability to use detailed description in formal English language, a thing in which he is totally capable, even though he prefers demotic in some contexts. Frustration is palpable: ‘Mum, I’m just trying to …’ and trails into the silence of that unspeakable to one’s mother. There may be something of piety in the project of this book – to honour ones migrant elder – but there is also sign of the power the adult educated young male has over their under-educated and obviously older mothers, whose terms, for mental illness for instance, lack sophistication.

This is easily readable in the text but gets missed when critics are keen to see this as a story of one’s mother’s trials as a migrant, pure and simple. A good example of how missing nuance in the characterisation of Kwesi, the son, that shows he is as limited by his own self-conceptions as his mother comes in the review by Zyomuya, who feels as an African origin son himself he understands this novel:

This “factless interview”, in the narrator’s words, could never retrieve the intimate and difficult details of his mother’s life since that moment of arrival: I find a certain type of African mother to be as reticent about their lives as an uncooperative suspect in a police investigation

Do other readers find, as I do, a hint of unconscious oppression in the singling out of a ‘certain type of African mother’ (a stereotype in fact) that misses the point of her having a story before we ask her about it. I do not say this from a position of blame. I think I was like this about my own white working class mother to my shame, without ever knowing why this was so oppressive. Of course, mothers often sweep such sonly behaviour under the table. Lol. Did mine? Not telling.

However, I love Zyomuya’s final assessment of the book (although he misses the essence of patronage to under educated migrant women in the process, and hence part of its knowledge of intersectional oppressions). He says, quoting Owusu:

“an immigrant woman who will die here alone and can only rise with the body of work her son has done well”. And by extension it is a living memorial to the millions of people labouring in care, cleaning and other low-paid work. [25]

Owusu is a great writer. Do read him in this and his other work.

Love

Steve

[1] Derek Owusu (2022: 142) Losing The Plot London, Edinburgh, Canongate

[2] Ibid: 38

[3] Note to above sentence, in margin of ibid: 38

[4] Percy Zvomuya (2022) ‘tribute to an émigré mother’ in The Guardian online[Sat 12 Nov

2022 07.30 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/nov/12/losing-the-plot-by-derek-owusu-review-tribute-to-an-emigre-mother

[5] Rabeea Saleema (2022) ‘a stirring ode to motherhood and life on the margins’ in The Irish Times online[Sat 5 Nov 2022 01.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/review/2022/11/05/losing-the-plot-by-derek-owusu-a-stirring-ode-to-motherhood-and-life-on-the-margins/

[6] Zyomuya op.cit.

[8] Antonia Burke, Seth Nyarko & Dorothee Klecha (2011: 1194) ‘The stigma of mental illness in Southern Ghana: attitudes of the urban population and patients’ views’ in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 46: 1191 – 1202 downloaded from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3192946/

[9] Owusu 2022 op.cit: 38

[10] Note to above sentence, in margin of ibid: 38

[11] See particularly ibid: 20

[12] Ibid: 153

[13] Ibid: 5

[14] Ibid: 58

[15] Ibid: 4f.

[17] They say: ‘…party militias remain a threat to Ghana’s democratic consolidation. [These militias] become active before, during and after elections in Ghana. Some of their activities that undermine democratic consolidation behaviourally, attitudinally and constitutionally are: stealing of ballot box and rigging of elections; the use of arms; violence against citizens and the opposition; forceful takeover of state property; destruction of state property; security role in political parties; placing significant demands on political elites; and the continuous clashes between party militias of the two major political parties of NPP and NDC’. From Emmanuel Graham & Henry Hagan (2021: 7) ‘Party Militias in Ghana: A Threat to Democratic Consolidation’ in Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs (online) Volume 9, Issue 8. Available at: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/party-militias-in-ghana-a-threat-to-democratic-consolidation.pdf

[18] Owusu 2022 op.cit: 3

[19] Ibid: 25

[20] Ibid: 29

[21] Ibid: 103

[22] Note to above quotation on nkwam, in margin of ibid: 103

[23] Ibid: 115

[24] Note to above sentences, in margin of ibid: 115

[25] Zyomuya op.cit

3 thoughts on “‘So, I’m here with my mum to ask a few questions about life’. ‘… – yes, she will continue to fashion herself to help give her bodam * grace – the obstacle of items will slow down this impedance’s pace’. This blog examines how and why we need stories wherein everyone, even the story has ‘lost the plot’! It concerns Derek Owusu (2022) Losing The Plot London, Edinburgh, Canongate.”