“I have a Ganymede brought from Florence that Mr. Hilliard, the painter, has much commended. It has a rare beauty. The boy is looking up at the eagle without a trace of fright; you would say he was some child, innocently watching a falcon”.[1] This blog looks at the theme of surrender to superior power, service, sexuality, play and gender in Bryher’s 1957 novel, The Player’s Boy London, Collins.

My copy of the book and some contexts worth exploring

At one point the hero of the novel, the obscure eponymous player-boy in it, James Sands (obscure not only in class because nothing much is known of the original Sands, other than his name and the items he inherited from the death of masters), says of his colleague ‘player’s boy’ Dicky that ‘he could do anything with that body of his from the day he joined us’. Us in that sentence refers to the King’s Men theatre troupe in which Sands was thought to serve.[2] This is, in context, a comment on Dicky’s acting skills and their repertoire. That matters because Sands feels comparatively somewhat of a misfit as an actor. This feeling is reinforced by Dicky’s ability with ‘parts’ and particularly female parts: ‘There wasn’t a part he could not play’ …”. The consequence of this superiority is that it is easier for Dicky to ‘slip into parts I ought to have played’, Sands says. But Sands is anyway of that borderline age (perpetually it seems in the novel) which forced acting companies to recognise that he ‘looked clumsy in petticoats earlier than most boys and was still too sturdy and childlike for a gallant’.[3] Hence he is somewhat of a misfit not only in theatre, but in the ‘real life’ playing any gendered-role. Moreover he characteristically confuses a theatrical role for one he feels he would like in that same ‘real’ life.

Love as a state of relationship to others in particular takes on this colour of playing at (and in a sense therefore also ‘having’) a desired role in social and amative relationships or those enabling him to survive n the changing economy of his period: hence the importance to him of the phrase ‘Love is service’, as we shall see. On the cusp of making a transition to heterosexual desire for a woman (Mistress Ursula, the betrothed of his master (Francis Beaumont)), he sizes up his love in fantasy at least in terms of two different kinds of earlier lover both male (an employing master and teacher and a comely young sailor lad Martin slightly older than he):

all that I had ever felt in it, my love, my brief glory with my first master, Awsten, the long, innocent playtime with poor Martin. “It is so beautiful I am afraid of it,” I stammered.

Forced to elaborate by Ursula, he sees love as a moment in time where the future of his desire colours the present, so that it stops being experienced as lived ‘in memory’: it is ‘the full sensation of a moment’. [4] That moment he exemplifies in Beaumont telling Ursula and himself the story of the Rape of Ganymede: ‘Do you remember, about the boy and the eagle’. It is a moment of transcendent pain wherein literally and metaphorically elevated vision meets loss:

“We are lifted up. We cannot apprehend where fate is taking us, it stretches our senses until we lose our grip, and drop. It can never be again and yet it never ends”.[5]

The use of the slightly covert Ganymede reference here is vague. It doesn’t mention that the mythical Ganymede held on to the fearful claws of the eagle avatar in order to give its lordly prototype, Zeus, later service (as a serving wine-bearer and sexual object) on Olympus. However, for me, it spices up not only the crossed genders but the age, class or status discrepancies in the three moments it illustrates. To love a master as a servant is as heady an elevation, with as uncertain a goal, as to serve him sexually, even in the innocent fantasy of loving Martin. Nevertheless he fears to climb the fearful rigging of a merchant ship with Martin or to winter with the same in the economic and queer fantasy of a South Seas colony. Sands is a bore but he has some strong fantasies. We shall see that later in relation to that tremendous and real play by Francis Beaumont, Philaster (c. 91ff). However for now, let us stay with the Rape of Ganymede.

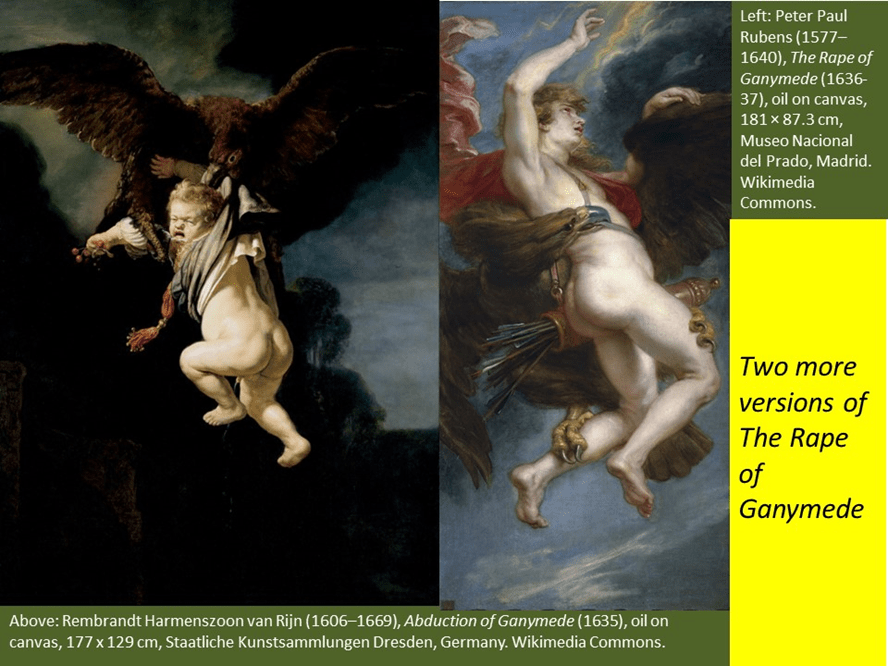

Both the earliest known representations of this story and that of Correggio shown above depict no fear of a fall in the face or attitude of Ganymede, which occurs in Sand’s short version, but a triumphant joy in elevated flight equivalent to the status he will bear, at least in relation to other humans, as immortal servant to the Gods. Flying is a creative state in this novel and almost equates to the creative freedom from the physical supposed of an ideal artist. Sexuality is implicit but is referenced in the taking of that boy.

In contrast, Bryher’s The Player’s Boy is not a racy novel, although ‘flying’ is a major imaginative experience therein. Its language, and indeed its reference to cross-dressing, is considerably tamer and covert than that of the play Philaster by Francis Beaumont, which (with its author) feature so heavily in The Player’s Boy. Philaster, the play, hangs on the supposition, however, that it is inconceivable that two women may have sex with each other, for this alone (when the pageboy Bellario is discovered to have been the girl princess Euphrasia and not a boy all along) saves the heroine Arethusa from being thought to have lain carnally with them. This is a supposition often referred to by Shakespeare and Marlowe too but most often with irony. Of course, although there is no explicit queer sex in The Player’s Boy, there is lots of reference to the queer coded within it, not least those in my title, which is in a speech by the once boy-actor, Dicky, but who is now living in luxury in the keep of courtiers. In it he refers to a gift to him (presumably from a courtier) of an Italian painting which tells a slightly different version of the myth of the Abduction (or Rape) of Ganymede. It is a picture, Dick says, admired by another genuine historical persona brought up here, Nicolas Hilliard.

“I have a Ganymede brought from Florence that Mr. Hilliard, the painter, has much commended. It has a rare beauty. The boy is looking up at the eagle without a trace of fright; you would say he was some child, innocently watching a falcon”.[6]

What matters here is that the ‘fear’ so central to the same myth in Sand’s earlier version (cited above) is entirely absent, as it is in those examples of visual art I have already shown above. Sands version is nearer to those visual takes on the subject below, with their different views of power taking advantage of vulnerability.

It is not surprising that the versions for each boy-actor would differ in this way. As I have already shown, Sands believes Dicky ‘could do anything with that body of his from the day he joined us’. Is there not here a suggestion, as with the ‘pout’ characteristic of Dicky, that, in the context of so many single-sex trysts, one role the player-boy might have is to make his body available to those who might pay for it: rewarding him with status, security and fine Italian paintings, as well as the company of courtier painters like Hilliard. The evidence that the boy-player experienced sexual abuse, or exploited his body, in the acting troupes is slim, although it is the subject of sly jokes in Elizabethan drama, as in Ben Jonson’s The Devil is an Ass, in which a female gossip speaks innocently of:

….. Dick Robinson

A very pretty fellow, and comes often

To a gentleman’s chamber, a friend of mine. …[7]

The references are barely hints however in Christopher Marlowe, who has his character Gaveston, the lower class lover of Edward II in the eponymous play, describe a court masque wherein is told the story of Actaeon viewing the Goddess Diana bathing:

Sometimes a lovely boy in Dian’s shape,

With hair that gilds the water as it glides,

Crownets of pearl about his naked arms.

And in his sportful hands an olive tree

To hide those parts which men delight to see,

…[8]

Lots of reasons are given by academics (they are summarised favourably by Joy Gibbon) for believing that the fact that some men have always had, or desired, sex with men as an absence in art. These reasons include the correct view that the term homosexuality was a nineteenth century one applied to a nineteenth century sexology.[9] The best example (and a honourable one academically speaking) of these arguments is a paper by David Cressy.[10] But the latter consideration is an irrelevant issue since sex between men in real life and artistic representation has never needed the definition and example it got in the nineteenth century that it applied to only one type of person labelled by whatever name. The issue is that sex between men was not a reserved area and could be acknowledged whilst it was being simultaneously condemned, sniggered at or kept at the level of hints. For instance, Marlowe above knows that the ‘parts that men delight to see’ might refer to Diana’s imagined and unnamed vagina but slyly allows the fact that it might be the player boy’s own penis that is referred to as part of the titillation of the piece, because that organ needed to be hidden by boy players to ensure they passed as a woman.

Moreover, there is no doubt that the theatre was considered ‘whorish’ by contemporary Puritan commentators because it mattered not what kind of sexual unions it allowed but that it allowed them without any boundaries being set at all. In effect dressing up at all worshipped figures and idols not the invisible God. Thus the behaviour of Elizabeth I’s court in which rich and figurally symbolic clothes were flaunted is described as being like ‘Popish service, in the devil’s garments’ whose playful behaviours consisted of ‘feigning bawdie fables gathered from idolatrous heathen poets’. Sexuality that dressed up was anyway readable by Puritans as innately sinful and labelled either idolatry, and thus like Catholic observance, or as adultery by John Rainolds, the tutor of the Anglican divine, Richard Hooker and initiator of what became the King James Authorized Version of the Bible. Wikipedia records that:

In 1566 he played the female role of Hippolyta in a performance of the play Palamon and Arcite at Oxford, as part of an elaborate entertainment for Queen Elizabeth I. … Rainolds later recalled this youthful role with embarrassment, as he came to support Puritan objections to the theatre, being particularly critical of cross-dressing roles.[11]

French King Henry III was fond of wearing women’s clothes at court (PA). From https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/miniature-portrait-french-king-discovered-b1792685.html

Indeed he says (the language of the original is preserved:

For being to proove that the prohibition of men to put on womens raiment (in Deuteronomie) belongeth to the mo∣rall law, and therevpon declaring how it is referred by learned Divines, to the commaundement, Thou shalt not commit adul∣terie: I said that they had reason to referre it so, because, among the kindes of adulterous lewdenes, mens naturall corruption and vitiousnes is prone to monstrous sinne against nature, as the Scripture witnesseth in Cananites, Iewes, Corinthians, other in other nations, one with speciall caution Nimium est quod intelligitur; and the putting of womens attire vpon men, may kindle great sparkles of lust thervnto in vncleane affections, as Nero shewed in Sporus, Heliogabalus in himself; yea certaine, who grew not to such excesse of impudencie, yet arguing the same in causing their boyes to weare long heare like women.[12]

To fancy that Dicky used his sexuality to gain preferment therefore is not outside the realms of something Bryher too might have been slyly suggesting in 1937 is not an extreme fancy. Dicky in contrast can inhabit with ease any gendered role (or part) he pleases, as I observed in my first paragraph. And that Sands should be obsessed with this I said there was in part because of his discomfiture in most gender, and indeed sex, roles: Sands is a misfit we remember as a girl or a boy gallant.amongst the King’s Men. This is explored in the novel’s treatment of Beaumont’s Philaster.[13] Moreover, the action of the novel covers Beaumont’s life from the time he becomes Sands new master as the very time that he was writing the play, trialling it at a reading and staging its first production in Southwark.

In the trial read-through, Beaumont himself reads the part of Philaster and Sands that of Bellario. Indeed Sands believes that those parts, and its assumed relationship, was meant for them for them both. In Sand’s fantasy the play told his life-story as he like to tell it himself, in the person of Bellario. In the novel Sands’ story is sometimes cast as that of a changeling and he is thus addressed at the point of his discovery by Augustine Philips (or Awsten as he comes to be known) who refers to Sands as if he were the invention of a playwright under the influence of Queen Mab. It is clear that from thence Sands feels himself to be bound in the theatre’s fantasies.[14] In acting as the Bellario ne thinks he is, Sands projects impossible future fantasies that edge on sexual conquest, not least of Beaumont’s betrothed Ursula despite her difference from Sands in class. As the trial reading begins, he thinks of the play’s narrative:

I wished that I had dared to whisper to Ursula before we parted in the evening dusk, “Mark the story. It is almost my own.” Bellario had loved Philaster but because of the difference in rank she had followed him disguised as a country page. So Awsten had found me; and in almost a repetition of the incident, Mr Beaumont had encountered me, sitting up[on a log beside the stream. Philaster had given his boy to Arethusa whom he loved, as Awsten had had to give me up to Mr. Sly. I am Bellario, I thought, as Mr. Beaumont rose to read his part, with a slow, beautiful motion as if the globe were his plaything and his lines the air. Love was service, and sometimes I did not know which of the two I wanted to be with; but to-night I was swept by an overmastering desire, I wanted to take Ursula back into the hazardous woods and show her that I could be as wild and ardent as my master.[15]

This is rich in sexual suggestion as Sands imagines what appears to be a wild seduction, if not rape, wherein he ‘shows’ a woman that he is a man. If we are inclined to think the phrase ‘Love is service’ is sentimental (it is the most vital phrase in the novel’s repertoire of themes), we ought to remember that Beaumont uses the term in Philaster to suggest a man pleasuring a woman sexually. Questioned by his daughter Arethusa about why Bellario, here supposed still a boy, is being sent to prison, the King says: ‘Put him away, h’as done you that good service, Shames me to speak of’.[16] Yet the original play is throughout about service taken in the name of love. It is the reason Euphrasia has taken Bellario’s pageboy persona in order to serve, as a servant, the man she loves. However, even as a boy it is appropriate, if exceptional to Bellario’s degree, that they speak of loving their master and his service as an indicator of that love with no sexual charge on the word at all. Philaster expresses it thus, wherein the term ‘boy’ already means ‘a page, a boy that serves’ a master:

The love of boyes unto their Lords is strange,

I have read wonders of it; yet this boy

For my sake, (if man may judge by looks,

And speech) would out-do story.[17]

In the Bryher novel, Sands sees the love of Bellario for his master as the equivalent of his for Beaumont, with the complication that it is sometimes also directed at his Master’s betrothed (an ‘overmastering’ desire for certain) and sometimes in wishful fantasy makes him Ursula being addressed as lover by Beaumont. Persuaded powerfully, as a master does, to play the part again in the Southwark production, Sands confuses his emotion in the play with that to his Master and imagines himself as the betrothed lady, Ursula, and himself is melted like ice by fire.

He took me by the shoulders, and shook me. The ice seemed to melt, my tongue loosened, and the first lines that I had to speak in the play tumbled out of my mouth.

“Sir, you did take me up

When I was nothing; and yet am something

By being yours.”

But I hoped he would understand that these words meant to me – … let me be your page, …

“That’s better, boy,” Beaumont smiled at me as if I were Ursula.[18]

It is as an actual pageboy that he would ‘serve’ (suit yourself which reading you understand here) masters rather than a fictional one like Bellario – whom, we have to remember remember turns out to be a royal girl, Princess Euphrasia, anyway in the play. It is Dicky who plays the chaste Princess Arethusa, the lover of Philaster, in Beaumont’s eponymous play, and in which role he is murdered leaving the stage clear for Euphrasia to marry Philaster. Bryher learned that those complications in which desire negotiates with the possibility of realisation involved shifts of class, gender roles and sex which she had to face in real life from Beaumont’s play as if these were her and its intention. Indeed I believe they were, for they mirror her issues about ‘being a boy’ (about which I have written in an earlier blog – follow the link to read it). The dialectic of master – boy (or indeed master – slave) appears in all the love relationships in A Player’s Boy. Look for instance at the reason for the demise of Sands’ earlier passion for Ursula at the play-reading already cited. [19] Realising that class got in the way of a romantic/sexual relationship that he might have for a woman more, in fact, than it might with a man (for the latter is disguisable), his object becomes thereafter not Beaumont’s betrothed but Beaumont himself, as the latest of the masters amongst whom he is exchanged. There is dark intent for me for Sands in the fact that Master Humphries later tells him that he may, unlike Dicky, have ‘changed masters too often’.[20]

Men though do not need to bow down to social mores in choosing a boy, for any reason but in this case to ‘serve’ them, as they would in choosing a girl as a companion, as long as they respected some discretion in the contract between them. Even when the distance between superior man and boy is smaller socially any tryst will depend on relaxation of a great many social mores. This is why the ghostly voice of that strapping sailor Martin returns to Sands when he is released of fantasy about Ursula and forced to take into account that only in poetry dare boys (although the tragic story of Icarus is foreshadowed in the prose as well as the relative successful one of Ganymede) ‘fly with Mr Beaumont, to be fluid, to rise, to come to golden answers falling from the sun, and sweep forward with the new, grand tide into motion and discovery’.

I did not see Ursula in the semi-circle of darkness. Instead I heard a whisper mocking me again, “Sands, fellow, I know more about thee than thou thinkest, why didst thou leave me; in the Indies all are equal’.[21]

Available at: https://snr.org.uk/training-and-education-in-the-elizabethan-maritime-community-1585-1603/

There is something of Bryher’s belief in the socialist nature of DEVELOPMENT in all these dreams, but also in her acceptance that such dreams are constantly being curtailed by the economic rationale of capitalist society that means to endure and maintain distinctions between persons based on the possession of money. Martin had offered a kind of life in the South Seas away from the mores of conventional society. Such a life is one possible development beyond Sand’s servitude and the codes of secreted desire. For Martin offers him a more open male desire, even if it had to be in the South Seas: saying that the younger boy had ‘aped a maid so long it is time I taught thee to stand on thine own legs’.[22] In the novel social relations become tainted by capitalism more and more as it progresses in the passage it records from an Elizabethan golden age (a myth of course) to Stuart negotiation with capital. Sands’ final Master is Mr Penny, and the name is iconic. And even then Sands must learn that loyalty between master and boy is probably a thing of the past when each must serve their own interests: Sutton says as he urges the betrayal of Penny by Sands: “So you see, I am not asking you to be disloyal but only to be reasonable”.[23] Times have changed indeed in terms of the distance of ‘service’ from love in a wage economy. Sands dies knowing that what is worse than death is the loss of all fluidity of development. As he says: ‘It was less the grave I feared than the slow, gradual extinction of all growth’.[24]

Commonly this novel is seen as about the kind of social change analysis which obsessed Bryher (of which the beheading of Sir Walter Raleigh as a pirate in the novel is the symbol).[25] However, even if so, change comes with other psychosocial concomitants and Bryher’s interest in sex/gender fluidity is part and parcel of all this. For Martin the sailor explains to Sands that he believes in fair trading abroad rather than the colonial imperialism he associates with Spain. And more importantly he looks to attract Sands to him as a practical proposition of a sailor to a man who needs company and much besides on ships where no woman treads. [26] There is bromance, of course, in this but also something of sexualised allure that burns above the practical:

He came towards me with a thick cloak he had begged or borrowed over his arm. A silver ring dangled from each of his ears. I knew, as I looked up, that under the surface our friendship was as deep as ever; he wanted me as much as I needed him; … “Fix thy mind on thy desire, boy,” Master Awsten had often said to me, “and in time thou wilt achieve it”.[27]

Yet Sands is queasy and he refuses this offer. With it he refuses the chance to develop sex/gender and other roles within more fluid relationships as he passes from it to the exchange economy (of masters, interests, money and opportunity) of the rest of the novel. To be called Sands (though the name is historical not invented) is useful when one is the subject of TIME. One either develops or is swept away by the tide or one falls endlessly through a hour glass, the ‘sands of time’. When Sands realises that anyone not a ‘gentleman’s son’ must model themselves in England now on the merchants of Cheapside, he realises that though he ‘wanted these warm, drowsy moments’ of his past ‘to last’, time is like the rain, ‘falling heavily and coldly’ with ‘regular beat’. It sings: “Time goes on. Time never turns, Time goes on, al all men with it.”[28]

This novel is wrongly neglected. It has a freshness that matches its importance but, despite its post-modernity of the theme, it has gone the way of literature generally. Who knows Elizabethan drama as Bryher knew it with no interest in knowing it, such as an academic tenure? In part this was because she rejected institutional learning for her own. But we, benighted, lie in a world which will rub out all the critical enquiry that Bryher associated with learning with our time-serving institutions of higher learning leading the way.

We just have to keep reading and thinking outside that box. This novel is a good start.

Love

Steve

[1] Bryher (1957: 123) The Player’s Boy London, Collins

[2] Ibid: 178

[3] Ibid: 122f. variously.

[4] Ibid: 85

[5] Ibid: 85f.

[6] ibid: 178

[7] Cited Joy Leslie Gibbon (2000: 30) Squeaking Cleopatras: The Elizabethan Boy Player Thrupp, Sutton Publishing Ltd.

[8] Cited ibid: 104

[9] Ibid: 182f.

[10] David Cressy (1996) ‘Gender Trouble and Cross-Dressing in Early Modern England’ in Journal of British Studies 35 (October 1996): 438 – 465. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/386118

[11] Available at: John Rainolds – Wikipedia

[12] Th’overthrow of stage-playes, by the way of controversie betwixt D. Gager and D. Rainoldes wherein all the reasons that can be made for them are notably refuted; th’objections aunswered, and the case so cleared and resolved, as that the iudgement of any man, that is not froward and perverse, may easelie be satisfied. Wherein is manifestly proved, that it is not onely vnlawfull to bee an actor, but a beholder of those vanities. Wherevnto are added also and annexed in th’end certeine latine letters betwixt the sayed Maister Rainoldes, and D. Gentiles, reader of the civill law in Oxford, concerning the same matter. Rainolds, John, 1549-1607., Gentili, Alberico, 1552-1608.Available at: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A10335.0001.001?view=toc

[13] The story of the play is in Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philaster_(play)

[14] Bryher op.cit: 28f. for ‘changeling Sands’. The forgotten of Queen Mab.

[15] Ibid: 91f.

[16] Francis Beaumont (location 745) Philaster: Or, Love lies a Bleeding. Kindle: A public Domain Book

[17] Ibid: location 347

[18] Bryher op. cit: 106.

[19] Ibid: 92. ‘It was then I remembered her mother’s voice …’

[20] Ibid: 123.

[21] Ibid: 92f.

[22] Ibid: 46

[23] Ibid: 164

[24] Ibid: 180

[25] Ibid: 142ff.

[26] Ibid: 42

[27] Ibid: 62

[28] Ibid: 119-20. The italics are in the original.

One thought on ““I have a Ganymede brought from Florence that Mr. Hilliard, the painter, has much commended. It has a rare beauty. The boy is looking up at the eagle without a trace of fright; you would say he was some child, innocently watching a falcon”.[1] This blog looks at the theme of surrender to superior power, service, sexuality, play and gender in Bryher’s 1957 novel, ‘The Player’s Boy’.”