Colm Tóibín’s latest collected essays suggest that, at least in some way (perhaps in the way we call ‘denial’) his writing is an example of how Irish art and discourse is always, in the end, about ‘being Irish and Catholic’. But if so, I would argue, it is an Irish and Catholic identity queered into new beauty by the open scrutiny it once avoided, at least in public. This is a blog on the essays of Colm Tóibín in his 2022 collection of them, mainly from The London Review of Books: that is, Colm Tóibín (2022) A Guest at the Feast London, Viking (Penguin Books).

The book and the man: pictures from The Independent (Ireland) and The Guardian.

Kevin Power, reviewing these essays for the Irish edition of The Independent makes the following point about how this collection compares to our expectations:

Most writers who put together an essay collection look for some theme to unify the book; A Guest at the Feast doesn’t do this. But it doesn’t need to. If it’s unified by anything, it’s by the quality of Tóibín’s mind.[1]

An approach that looks for, and explicates, underlying themes attracts me very much when reviewing a beloved and favourite writer like Tóibín. According to Power though, this writer provides unity only by the fact that he meticulously ‘wants to get at the truth’ and to do so as even-handedly and fairly, even with regard to Catholic clerics, and their political allies, who systematically committed or facilitated the abuse of young people and children. But surely no-one could love a writer based only on the fact that the provided journalistic balance with regard to persons as well as issues, however rare that quality otherwise is. Nor could we love him just with the addition of this writer’s notorious critical percipience in the handing of art and culture of different genres. Power thinks, for instance, that this is the quality we love in the 2020 essay on Venice and the art of which it is the keeper, particularly art by Tintoretto and Titian, saying in summary of this essay: ‘Looking at the painting, he found that “my eyes were more alert than usual because of the early hour”. But his eyes are always alert; the guest at the feast is always watching closely’.[2]

Alertness is a wonderful quality but this essay appeals much more by the way it is overlaid by a network of ideas, emotions and values that add up to a person. I say ‘add up’ but this is a false metaphor for the sum of those ideas, emotions and values is not the result of a precise calculation but a way of demonstrating that many questions we may ask about our experience cannot be answered, or at least addressed, by looking only at the sum of each apparently separate feature of that experience. Good writers create the feel of unanswered and unanswerable questions about our humanity in its mortal and other aspects, whatever those others may be (and that is the main underlying QUESTION of all). Is there anything other than mortality in animal life – and specifically the human animal’s life?

The Tintoretto Crucifixion (and 2 details thereof) in San Rocco, Venice (see Colm Tóibín (2022: 288f). ‘Alone in Venice in A Guest at the Feast London, Viking (Penguin Books 287 – 297). Pictures available at: Tintoretto – Scuola Grande di San Rocco (scuolagrandesanrocco.org)

After all, what does the writer see in the ‘new emptiness that had fallen on the city’ under Covid lockdown, which he equates with added ‘clarity to the art’. His perceptions are manifold in their reference to different artworks and the contexts in which they are seen. First he sees a means of illustrating the paradox that art can be ‘illuminated’ in darkness (where ‘shadow satisfied the eye more than looking at it when illuminated’) in ways that make his use of what gives ‘clarity to the art’ of Venice, some fine nuance. In the version of The Crucifixion by Tintoretto at San Rocco (see above illustration), he notes that in dark but not in the electric glow of artificial illumination, the viewer sees its ‘mystery’ ( a rich word in Catholic ritual – for its etymology follow the link in this parenthesis): ‘in which ominous cloud hits against embattled light, in which the viewpoint is oblique, in which shadow does more work than light’.[3]

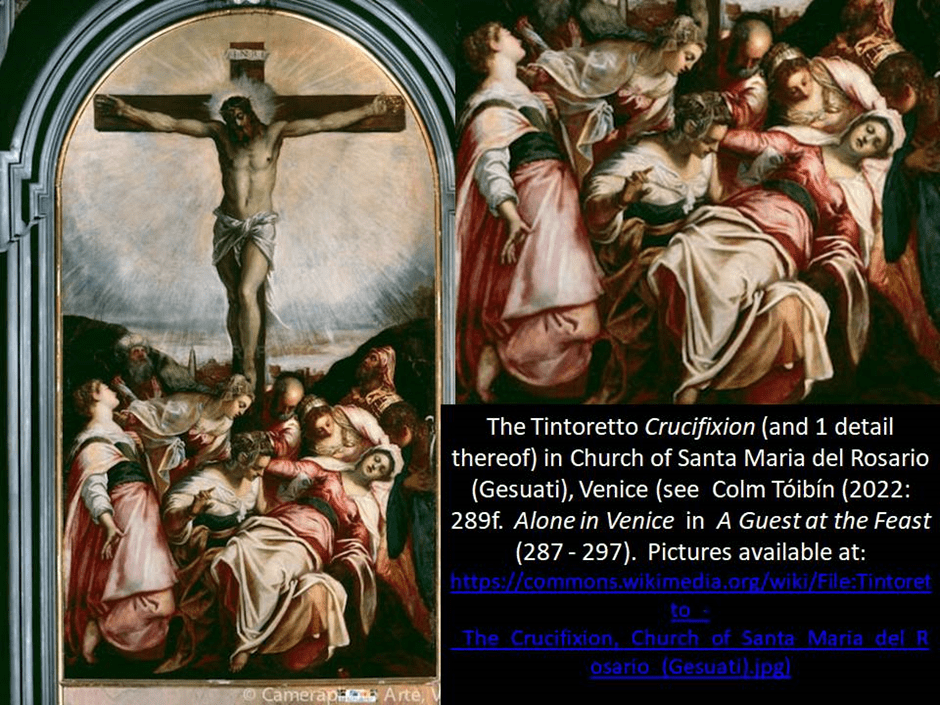

Another perhaps richer example, given the tendency of this book to explore the notions of the Catholic inheritance in Ireland, with punning reference to the word ‘mass’, appears when looking at a much less complex Tintoretto Crucifixion, that ‘towards the back of the Gesuati, a church overlooking the Giudecca Canal’. Though seen many times before by him, he notices how light focuses not the suffering Christ but ‘mourning figures below him’ (indeed if we look back there is truth in this regard with reference to the complex multifocal version in San Rocco mentioned before).

The Tintoretto Crucifixion (and 1 detail thereof) in Church of Santa Maria del Rosario (Gesuati), Venice (see Colm Tóibín (2022: 289f. Alone in Venice in A Guest at the Feast (287 – 297). Pictures available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tintoretto_-_The_Crucifixion,_Church_of_Santa_Maria_del_Rosario_(Gesuati).jpg

Colm Tóibín writes of this group about the ‘intricate and intense work done on their faces and robes’:

They were huddled together; the robes appeared to be made of all the same material, with the same few colours, thus adding to the idea of them as a mass, a shocked cluster rather than a set of individuals. They faced away from the hanging saviour; only two outliers looked up at the cross.[4]

The play on the word ‘mass’ appears as secreted as that on the word ‘mystery’ that we have spoken of before but all those meanings were made available by the view of sacralised art in the Council of Trent and are second nature in Catholic countries, such that even Catholics who lack belief, like Tóibín, use them when referring to aspects of life that ‘might’ transcend the mortal and impermanent. A mass is a crowd but it is also a sacrament. It is this underlying knowledge that makes us love this writer. This is all the more so when we see how he exploits the very absence of the overwhelming mass of ‘shocked clusters’ that characterises Venice before lockdown. And the presence of this theme (referenced as part ‘of the business of light and shade’) includes the dark and light (in another sense) in the human responses to the threat to whole masses of persons from epidemics or ‘plagues) that runs through the piece. It allows him to reference a visit ‘to the Lido’ in order to ‘look at the Grand Hotel de Bains, now a shell where Thomas Mann set Death in Venice’.[5] Conveniently, as the writer appears to add new detailed associations to this event, linking Mann’s writing directly to the theme of fear of epidemics and plagues that facilitated him transitioning to speak of having ‘his temperature taken the next day’ (as a caution against possible Covid in the immediate context) and to the appearance of the ‘mephitic terror’ of plague in 1575 shared by Titian, as recorded by Sheila Hale, so that we can move back to the discussion of artistic response to mass mortality, this time inTitian’s Pièta. He describes this picture, with his reasons, as: ‘Titian’s plague painting, just as Death in Venice is Mann’s cholera story’.[6] I would add that anyone doubting the potential of my reading might look at the final paragraph to this piece, which like a musical coda combines themes of the fear of mass death, the uses of isolation and the need to ‘think about light and shade’. This is writing that rejoices in the mysteries of good reading as the companion to good writing, for there is no use in the latter without the existence of the former.

I have taken some time to nuance Kevin Power’s perception of this book, because I feel it startling common to avoid looking for unity between occasional articles that get into collections like this; articles written by the same writer but at different times. I do this because as I read the essays commonality of purpose seemed to be there but, as it were, hiding under evasions of style and tone. I think this is a characteristic of Tóibín’s writing and his fine understanding of character in the novel and how that might be conveyed. There are brilliant examples everywhere but here is one I pick up from his neglected House of Names based on the Oresteia (use the link inside this parenthesis to see my blog on it, from which the following long sentence comes):

When Orestes, in the ‘house of whispers’ (page 213), that is Mycenae, hears the sexual congress of Aegisthus and his two favoured bodyguards, by following them to a remote palace room and waiting and listening outside, these ‘sounds were familiar to him and unmistakable’ but still do not get named.[7]

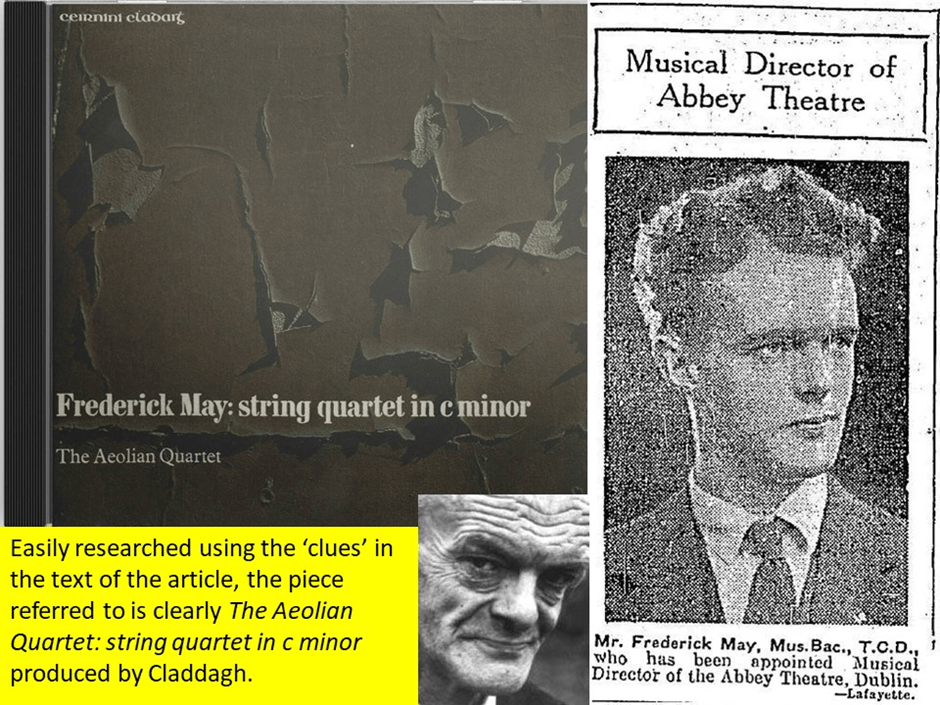

As a narrator in these journalistic essays too Tóibín uses evasion and stylistic devices, even frank contradictions. This is particularly interesting when he discusses how other artists might lay networks of references to underlying themes in their work. Here, in an autobiographical essay that gives the volume considered its title, for instance, he refers to his meeting with, and knowledge of the work of, the Irish composer, Frederick May. May’s ‘output’ is described by the Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland , cited in the essay, as ‘generally unknown, unperformed and in some cases in un-performable condition’.[8] Befriending May in a Dublin pub and loaning him John McGahern’s banned novel The Dark, he says of a piece that May loans him in recording that it ‘shocked me with its edge’. Yet he never names the piece as such, other than as a quartet, even though May is allowed to be recorded saying of it, that, ‘It wasn’t much’. Why not name it? It is as if the writer colludes in May’s disappearance from public knowledge whilst offering some insight into him. The piece is in fact easy to research and find using clues in the text (see the illustration below) but not to name it seems deliberate. Despite the public role of May in Dublin classical musical theatre, which is as unimportant as Tóibín as the plays put on by the Abbey Theatre of which May was director. But that quartet, still unnamed, is declared ‘one of the most exquisite contributions to Irish beauty that has ever been made’.[9]

What is going on here? Perhaps someone may think that I over-read all of these possible accidents in the prose of a jobbing journalist. But I do not think so. For let’s look at another statement by Tóibín on this ‘most exquisite contribution to Irish beauty’ to see the mystery deepen For he also says:

There is not a single Irish sound in the whole string quartet. Or maybe every sound is Irish. Maybe the unforgettable ending of the last movement, slow and plaintive, unwilling to finish, coming back again and again to a haunting melody, which is half offered and then withdrawn and hinted at and then lifted to an extraordinary pitch of beauty, maybe that is Irish. But I don’t think so; it is too easy to make claims like that’.[10]

The contradictions are extreme: ‘not a single Irish note’ to ‘every sound is Irish’. Then we shift to the idea that what is Irish exists in details of the structure, endings completed (which is incompletely) as only can be done in Irish aesthetic form. And, after all, the writer is right to claim that such ‘claims’ are valueless because they are much too easy to make. For me this relates to the ‘unity’ of this collection which is like what it means to be an Irish artist, brought up in Catholicism. I see the same sleight of hand in the essay on John McGahern. That writer, one I love perhaps because of the dark contradictions therein, which Tóibín finds so problematic because he recognises himself in them:

At the time The Pornographer came out, I had little interest in (John) McGahern’s work. I found too much Irish misery in it, too much fear and violence and repressed sexuality, too much rural life and Catholicism. Perhaps my aversion was made the more intense by the fact that I recognized this world. I had been brought up in it; I was still living in it’.[11]

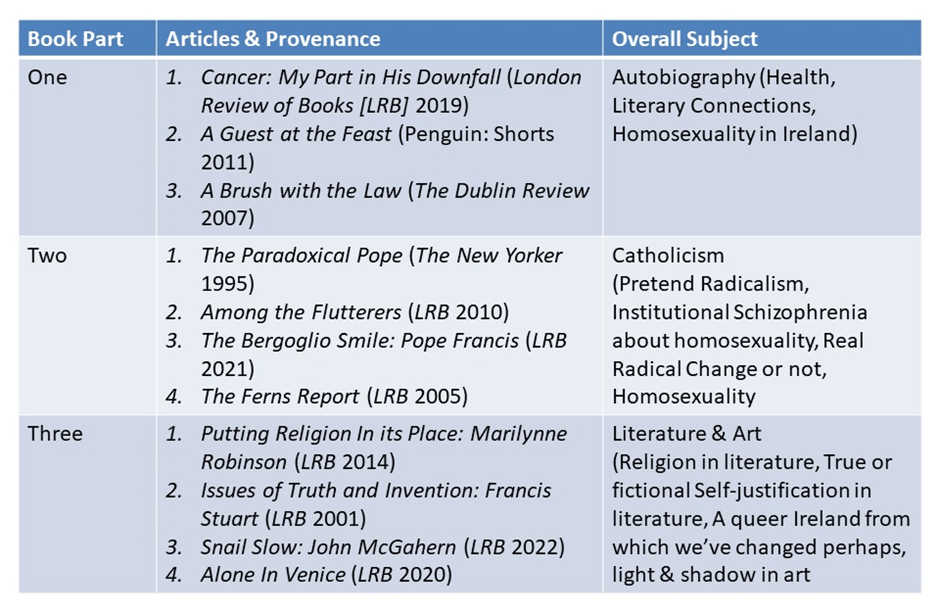

There is much that is, potentially, the summation of Ireland here, at least at this period of its twentieth-century history, but there is much too of the fragments that make up this book. To clarify this I determined to create a chart of the structure of the book, for out of structural fragments we might find aspiration to unity which I share later in this blog. Indeed aspiration is enough, for the writer said in an interview with Lisa Allardyce in 2021 in The Guardian:

“I’d love to have an integrated personality,” he once told a psychiatrist friend (he has a way of telling stories that sound like the beginning of a joke). Tóibín said: “The books are so filled with melancholy and I wander about like some sort of party animal.” “Well, which would you like to be?” his friend asked. To which he replied, “I don’t know.” “Oh go away!” the psychiatrist said. “I have serious patients with serious problems.” [12]

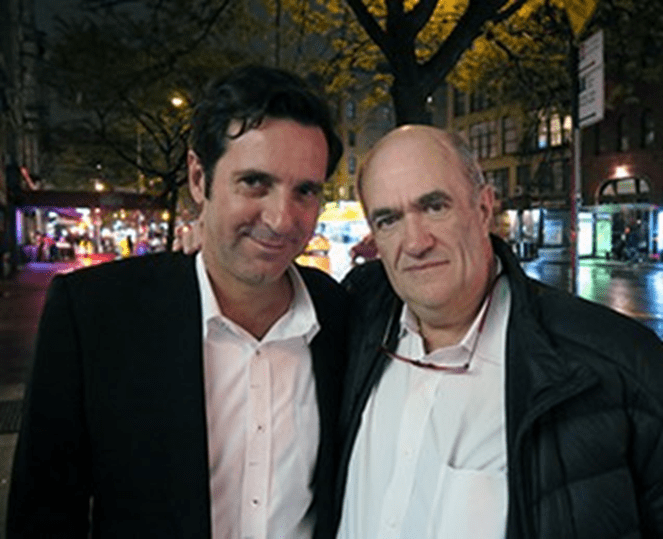

And within what demands integration and unity in the writer is the very Irish experience of John McGahern, but with a difference: with a positive representation (though there are some disturbingly negative ones as Toibin shows) such as you cannot find in McGahern. The positive representation may be as light and unnoticeable as the appearances, supporting Colm through cancer for instance even if from international distances, of his ‘boyfriend’ (the writer’s chosen term) the editor and semiotician Hedi El Kholti. For Tóibín sees his career as a surmounting of a heavily restrictive Irish past, politically, culturally and sexually, by a new outlet of Irish creativity. Nevertheless he has dotted his career with occasional strong spotlights on repressed queer men using, as Allardyce says:

this trick of inhabiting the inner-worlds of great writers to explore his theme of creativity driven by thwarted desire. [Henry James and Thomas Mann, each the subjects of two of his novels] were hugely important to him during his late teens and early 20s. Growing up gay in a small town in Ireland, “where homosexuality was unmentionable”, left him “fascinated by figures who had lived in the shadows erotically”. As always he was drawn to secrets, to lives lived between the lines, to the sense of James and Mann as being “like ghosts in certain rooms”, a distance created by their “uneasy homosexuality”, he says. “Mann’s was more self-aware than James, but you can never be sure with James. James’s work is filled with sexual secrets.”

Tóibín (right) with his boyfriend, editor Hedi El Kholti.

There is the same contrast of light and shadow here and we might note that Tóibín tells us that he meets Frederick May at The Stag’s Head in Dublin, ‘at its most beautiful and shadowy and stately’.[13] As we have seen it has a starring role in ‘Alone in Venice’. We might expect then the structure of this book to refract its themes through each part. I think even a cursory look at the chart below shows this is so, even if the reader must keep alert.

What unites the essays is a common interest in truth and fiction in self-representation and the representation of values, including especially those of religion (for much of it Catholic religion). These issues have consequences most when they touch on the representation of queer sexuality. The final three essays on Popes are obsessed with this concatenation of themes: from the manner in which an institution that inwardly fostered queer sexualities while outwardly professing an extreme of heteronormativity from the paradoxes of John Paul II to the strangeness doubleness of Pope Benedict, Joseph Ratzinger. The latter’s rule is described especially with reference to queer issues. John McGahern gets into the latter essay as he does ‘A Guest at the Feast’ earlier, for (even under the previous Pope) he demonstrates his severe dislike of ‘gay liberation’ by pointing to ‘the takeover of the seminaries by homosexuals’. The play with Pope Francis merely complicates how and whether Catholicism changes in the governing bodies that hold its secrets together. None of this is negative or just merely critical. As with Francis Stuart in the literature essays (though there Fascism and Anti-Semitism, of a deadly kind, is the belief system at stake), ’our interest’s in the ‘dangerous edge of things’ between truth and fiction as was that of Browning’s Bishop Blougram.

There is every reason to see both the divisions, their persistence and the desire for unity cutting across these essays as they yearn for an Ireland that does not need to slough off its Catholic past but to clarify the paths to transcendence it offers the post-religious. This is a great book. Read it. However, don’t expect to get to its lessons about a new queer and Catholic inspired Ireland easily, for evasion and denial is the key to entry therein as in all of this writer’s great prose pieces (and, we can now say, his poetry too).

All the best

Steve

[1] Kevin Power (2022) ‘A Guest at the Feast: Colm Tóibín’s quest for truth is a treat for the reader’ in The Independent (Ireland) online [November 03 2022 04:45 PM] Available at: https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/book-reviews/a-guest-at-the-feast-colm-toibins-quest-for-truth-is-a-treat-for-the-reader-42116824.html

[2] Ibid.

[3] Colm Tóibín (2022: 288f.) ‘Alone in Venice’ in A Guest at the Feast London, Viking (Penguin Books).

287-297

[4] Ibid: 289f.

[5] Ibid: 293. In part, I suppose, the visit was also a preparation for his novel on Thomas Mann, The Magician – follow the link to see my earlier blog on this novel).

[6] Ibid: 296

[7] See: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2020/01/18/colm-toibin-2017-house-of-names-london-viking-orestes-wanted-to-say-to-electra-that-neither-she-nor-anyone-else-in-the-palace-had-authority/

[8] Colm Tóibín (2022: 56) ‘A Guest at the Feast’ in A Guest at the Feast London, Viking (Penguin Books).26 – 80.

[9] Ibid: 60

[11] Ibid: 277

[12] Lisa Allardice (2021) ‘Interview: Colm Tóibín: ‘Boris Johnson would be a blood clot … Angela Merkel the cancer’: The acclaimed novelist on chemotherapy, growing up gay in Ireland and writing his first poetry collection at the age of 66 in The Guardian (online) [Tue 14 Dec 2021 07.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/dec/14/colm-toibin-boris-johnson-would-be-a-blood-clot-angela-merkel-the-cancer

[13] [13] Colm Tóibín (2022: 52f.) ‘A Guest at the Feast’ in A Guest at the Feast London, Viking (Penguin Books).26 – 80.

8 thoughts on “Colm Tóibín’s latest collected essays suggest that, at least in some way (perhaps in the way we call ‘denial’) his writing is an example of how Irish art and discourse is always, in the end, about ‘being Irish and Catholic’. But if so, I would argue, it is an Irish and Catholic identity queered . This is a blog on the essays of Colm Tóibín in his 2022 collection of them, mainly from The London Review of Books: that is, Colm Tóibín (2022) ‘A Guest at the Feast’.”