In reporting her dream, Hilda Doolittle (known as H.D.) to her friend and lover Bryher, H.D.: ‘It appears I am that all-but extinct phenomena [sic.], the perfect bi’.[1] This blog is based on reading Susan McCabe’s ‘bi-biography’ H.D. & Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism (2021) New York, Oxford University Press.

My copy of the bi-biography

I should start this blog perhaps with some justification for the term (coined by me) ‘bi-biography’ to describe Susan McCabe’s book. Of course, I want to indicate more than that this is a biography of two people who are deeply associated as artists, lovers and people of importance in their time (Bryher’s work in aiding Jewish immigration into Britain from Germany before and in the Second World War for instance alone would make her significant). It is also because both persons involved had male and female lovers. Indeed, both were married to men and were sometimes referred to (correctly in the name of the law) as Mrs Aldington (for H.D.) and Mrs Macpherson (for Bryher): H.D. having also had a sexual relationship with Bryher’s husband, Kenneth. Moreover, they identified not only between sexualities (homosexual and heterosexual) but between genders. They were people in perpetual passage between male and female in their writing, such that their identity and even bodies were thought of as something that ‘crossed over’ any boundary of the normative binary distinction. Both identified as spiritual mediums and boasted of earlier lives across sex/gender boundaries. Bryher (who also knew themselves as ‘Gareth’ and was addressed as such by H.D.) may have been surprised when H.D. challenged her recollection of the sex/gender of those past lives of Bryher’s with the words: “you can’t always be a boy. You were a boy in Elizabethan England”. H.D referred, of course to a ‘player’s boy’ who enacted female roles in Elizabethan drama. Bryher’s response was clear: “I was a man in Egypt and probably a woman as well, but I was a boy before that”. [2] Moreover, H.D.’s background in the Moravian church would have exposed her, McCabe says to ‘brethren’ who ‘believed that Christ’s “side hole” wounds, received at his Crucifixion, unified male and female’ without her needing to invoke the classical androgynes that appear in her novel Palimpsest. [3] In a late unpublished poem by H.D., she speaks of her co-identity with an R.A.F. airman which bridges their joint lives and deaths as well as sex/gender identities:

He could not know my thoughts,

but …

the invisible web,

bound us;

whatever we thought or said,

we were people who had crossed over,

we had already crashed,

we were already dead.[4]

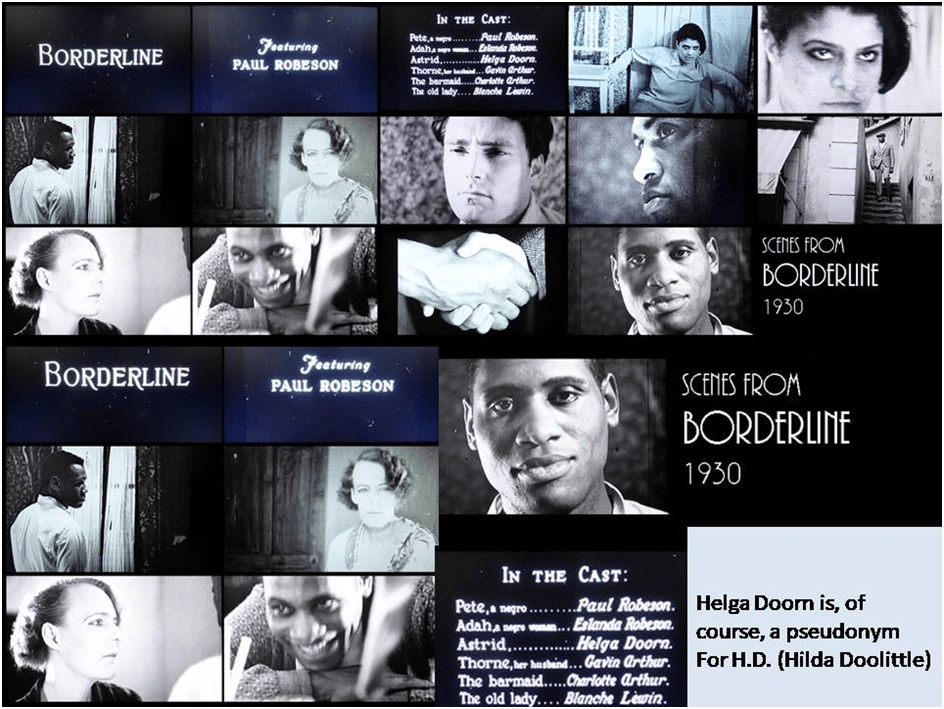

The same sentiments could be, and were, expressed about Bryher, or even her own male alter egos. Even before Susan McCabe evokes queer theory to discuss these writers, Louis L. Martz in 1983 cited the importance of the 1930 movie Borderline by the queer husband and sometime lover of H.D., Kenneth Macpherson, It was made by a production company (POOL) including (and using as actors) both H.D. and Bryher in which H.D. played Astrid, half of a couple living in a ‘borderline town’ in mid-Europe: ‘borderline social cases, not out of life, not in life’. They are matched by another couple (played by black actor, singer and activist Paul Robeson and his wife Aslanda) whom H.D. describes as dwelling ‘on the cosmic racial borderline’. Of her own part, H.D. says: ‘Astrid, the white-cerebral is and is not outcast, is and is not a social alien, is and is not a normal human being, she is borderline’. [5] There is no doubt her that the concern with transition across boundaries (the very heart of queer theory) was always central to H.D and Bryher and it is for this reason then as well I call this book a ‘bi-biography’: a book of innovative approach to not only sex/gender but to the concept of identity generally.

However, in order to pursue this queer line of thought I think it’s a good idea to step back to the basics of the thought of these lovers. My own preference is to start with their debt to Freud. In the brilliant prose-poetry of her Tribute to Freud (first published in book form in 1956 but written and serially published between 1943 and 1945, the turbulent latter years of the Second World War), H.D. summarises the genesis of psychoanalytic thought in the work of Sigmund Freud. [6] Fascinated most by the processes by which ‘the Professor’ (as she called him) developed thought that connected his own inner experience, revealed by him as lying underneath an apparently outwardly secure life, to the experience of the most marginalised and, to speak frankly, oppressed persons in the world in which he lived: ‘incidents unnoted or minimized by the various doctors and observers, which yet held matter worth consideration’ (my italics). Freud was special, H.D. felt, because he dared to compare his own experience, whether in dreams or ‘everyday life’ whilst awake, with marginalized people whose behaviours were perhaps deliberately unnoted or minimized, lest their experience show that what we label normal life was in fact akin the experience of ‘the mad’. Suddenly it appeared that the act of thinking ourselves to be ‘normal’ was allied to the active creation of physical, as well as mental, distance between the supposed ‘abnormal’ and ourselves: the mad must be ‘segregated, separated, in little rooms, …, or cells with bars before the windows or doors.’ Moreover:

He noted how the disconnected sequence of the apparently unrelated actions of the patients [in Charcot’s Salpêtrière hospital or amongst his private clientele] yet suggested a sort of order, followed a pattern like the broken sequence of events in a half-remembered dream. Dream? Was the dream then, in its turn, projected or suggested by events the daily life, was the dream the counter-coin side of madness or was madness a waking dream? [7]

Some books I use herein. Bryher’s novels and H.D. Collected Poems 1912-1944 new to my library. The copy of Palimpsest is that published in a limited edition of 500 for an Edinburgh exhibition.

That there is some similarity between the structure of dream and poetry did not escape H.D. and should be remembered if we attempt to read, in particular, her wonderful poetry (although the same was true as she noted of her contemporary T.S. Eliot). Poetry, dreams (of the night or daytime fantasy) and madness treated memories from daily life with a relative lack of care of differentiating memories that came from reading or listening to stories preserved in records from the past, fantasy or a combination of all these (as is usual in what we sometimes call ‘history’) from ‘real life’. If madness is ‘Hell’ its inhabitants ‘sometimes bore strange resemblance to things he had remembered, things he had read about, old Kings in old countries, women broken by wars, and enslaved, distorted children’. [8]

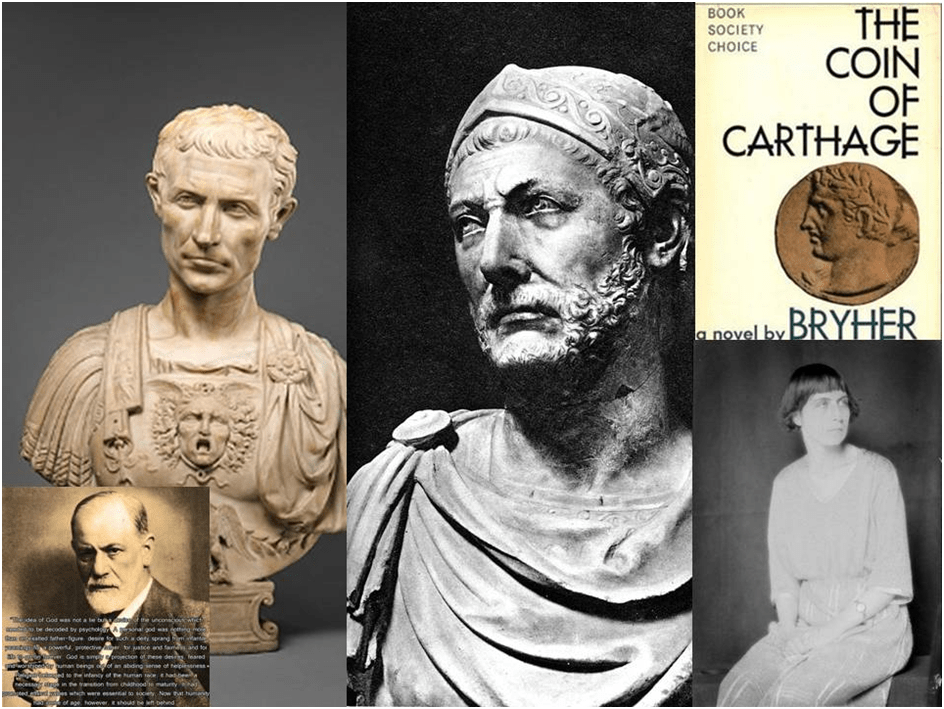

Characters from those strange, distorted histories. built sometimes of random stories collated by unreliable processes of associative memory, are very important in the connection between H.D., Bryher and Freud for both artists were friends, and sometimes consulting patients and research students, of the Professor and shared the relics of the sources of their lives including common memories and reading. I pick out one here one central to my argument – one that linked not only the fantasies but the theories of sexuality of all of them, even Freud’s now hated (but equally misunderstood) theory of ‘penis envy’ as a characteristic of female development. H.D concentrated on a favourite character of Freud’s daydreams and wishful aspirations, Hannibal of Carthage. I quote at length because this passage is as important as an index of what H.D does not say clearly about herself and Bryher, as well as about Freud and his discoveries about the similarities of his experience to a certain understanding of that of ‘mad’ persons, imagined in their ‘cells’ or ‘cages’ enacting roles in a ‘play’.

Caesar strutted there. There Hannibal – Hannibal? Why Hannibal? As a boy he had himself worshipped Hannibal, imagined himself in the rôle of world-conqueror. But every boy at some time or another strutted with imaginary sword and armour. Every boy? This man, this Caesar, who flung his toga over his arm with a not altogether authentic gesture, might simply be living out some childish fantasy. (… )But was it Hannibal? Was it Caesar? Was it – ? Well, yes – it might be – how odd. Yes – it could be! It might be this man’s father now that he was impersonating. (…) There must be something else behind many of these cases and at the Salpêtrière – not all of them – but some of them – and other cases … There must be something behind the whole build-up of present-day medical science – there must be something further on or deeper down – there must be something that would reveal the secrets of these states and conditions – there must be something…. Why, Hannibal! There is Caesar behind bars, here am I, Sigmund Freud, watching Caesar behind bars. But it was Caesar who was conqueror – was he? I came, I saw, I conquered – yes, I will conquer. I will. I, Hannibal – not Caesar. I, the despised Carthaginian, I, the enemy of Rome. I, Hannibal. (…) True to my own orbit, my childhood fantasies of Hannibal, the Carthaginian (Jew, not Roman) – I, Sigmund Freud, understand this Caesar. I, Hannibal![9]

H.D. imagines here a process of thought that is also one of feeling, and maybe of the sensation, like the feel of a ‘toga’ over one’s arm, the weight (and effect on one’s gait) of heavy armour and weapon. Her use of the first person, is always instructive – so easily mistaken for that of the writer of the prose, we often have to be reminded that I should here refer to Freud and his thought processes. Even so, however, identity is fluid for if I can imagine myself as Cesar (a ROMAN emperor), I can equally imagine myself an enemy of Rome (perhaps even as the hated bugbear of classical civilizations – the Jewish Carthaginian). All of these fluid identities speak of Freud’s deep wishes – to come, see and conquer the unknown lands, repeating Caesar’s conquest (as expressed in his own Latin as veni, vidi, vici) of unknown (to Rome at least) Northern lands. In Freud’s case these ‘lands’ were the unconscious (or das Es, or It, or ID). Ceasar famously wrote to the Senate his famous words in order to be praised for his conquests. But failing praise, there was also glory in the adventurous near conquests of (in Roman eyes) the rebel Hannibal defeating Rome on its own grounds. To be Hannibal would allow Freud to pay back the psychiatric community for its laughter at him as being like Hannibal, a ‘barbarian’ and ‘Jew’. H.D. spells out both of these possible identifications later. The conquering champion of the academic and medical realm of conventional psychiatry in the name of an analytic method which Freud surely wished to become can also be the outsider who rebels against the established orthodoxy and makes its power to seem more fragile than it had erstwhile been. He would win, in doing so, even if his victory depended entirely on imagined glory; as if Hannibal became Caesar in the imagination. And if these identities can apply to him, cannot they also apply to other versions of the ‘das Ich’ (Freud’s term poorly translated by James Strachey as ‘the ego’) including that used by H.D. to name her conscious self.

H.D.’s prose ventriloquises Freud saying: ‘But every boy at some time or another strutted with imaginary sword and armour. Every boy?’ The reason she italicises ‘Every boy’ must, on the surface at least, be emphasising that if this identification was possible for Freud, this fact made it clear to him that it may apply to any and every ‘boy’. After all, all ‘men’ in patriarchal societies inherit the entitlement to make themselves known, in some way or other, and not necessarily as a famous Doctor or Professor. For some that ambition may be to be as good as, perhaps even competitively BETTER, than their dad. But there is another reason to italicise the phrase ‘Every boy’. For can what applies to boys not also apply to girls, nay to persons generally! H.D. deflects from direct statement of such themes, though she ends this section of the book by wondering what Freud had to say to ‘Caesar’s wife’. But it clear, to me at least, that H.D. did want this area of identity (as adventurer, conqueror and rebel) not to be denied to women. It matches other areas where she writes in ways that challenge binaries as the irreducible basis of human identity – not just binaries of male and female, but also, for instance, of human and animal, living and dead, real and imaginary, prose and poetry, established and innovative, conservative and rebel.

There are lots of ways, other than the fact Bryher wrote a novel about the historical Hannibal (The Coin of Carthage), in which the importance of a Hannibal identification (as one of many ‘boy’s’ heroes) is made clear (without DIRECT statement as such) in Susan McCabe’s bi-biography of Bryher and H.D., some of which I have noted above in my first paragraph. However, the idea is even clearer in Bryher’s 1920 novel Development. Bryher’s hero in her first novel, Nancy, finds in the figure of Hannibal the mode of her introduction to writing. Even as a 9-year-old child, Nancy, a thinly masked young Bryher, writes of ‘Hanno’, the ‘Carthaginian boy’ of ‘nine years old’. [10] Hannibal is the stimulus to synaesthesia in art, history, adventure and the exploration of the borderlines of identity and provided a boy hero of her own age whose greatness was shaded only by the ‘cupidity of an effeminate Carthage’. [11] Bryher writes:

Beside Hannibal, fiction or fairy tale was dull as an etching to an eye avid of colour; still books that treat of Carthaginian life being inaccessible to childhood, to assuage a hunger for literature that should bear at least the name of Hamilcar or of Hanno in its pages the inspiration came to Nancy to write a story for herself. / … A boy must occupy the centre of the story. To her, Carthaginian girls existed merely in a fabulous way.[12] [my italics]

Visiting the site of Carthage itself 3 years later Nancy searches but finds not ‘even the name of Hannibal met her eyes’. [13] The increasing abstraction of what is meant by ‘being a boy’ characterising Bryher’s novel takes a definite turn when Nancy reads the ‘final acts of Antony and Cleopatra’. Through the fictional recreation of the real Cleopatra, considered by her as ‘worthy’ of (being) a boy’, the value of being a boy’s value becomes resolved into its spirit not biology (if it ever was that) made up of rebellious action, adventure, the will to conquer, pursuit of ‘freedom’ and the disregard of physical death in an internally defined noble aim.

Here was real fighting. Cleopatra’s spirit was worthy of a boy, Anthony, who threatened disappointment, died in armour. She read on eagerly; this was an adventure.

… Lifted above all that, by her very immaturity she could but crudely understand, she was conscious of an exaltation felt but once or twice before only, the knowledge these pages guarded an immortality as strong as the rich antiquity she knew; an explanation of greatness that effaced the desolate memory of the few stones left of the city that had nurtured Hannibal and betrayed him.

Give me my robe. Put on my crown. I have

Immortal longings in me. Now no more

The juice of Egypt’s grape shall moist this lip.

Yare, yare, good Iras, quick. Methinks I hear

Antony call. I see him rouse himself

To praise my noble act. I hear him mock

The luck of Caesar, which the gods give men

To excuse their after wrath.—Husband, I come;

Now to that name my courage prove my title!

I am fire and air; my other elements

I give to baser life.… This was the spirit that taught Hannibal to conquer; in this spirit he accepted death. But more than the fierceness of it, it held loveliness.[14]

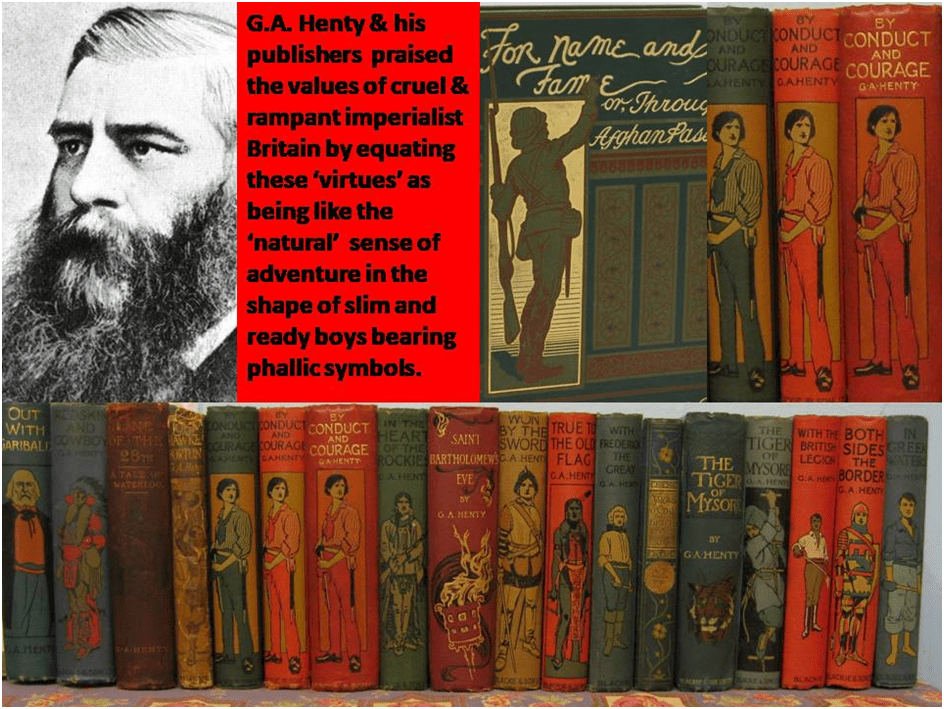

Such worthiness as shown by Cleopatra’s noble act of suicide was in Nancy’s (and, of course Bryher’s) prior imagination represented only by being a boy with ‘boyish’ yearnings for outward adventure and independence – the stuff Bryher gained, it is thought, by reading the novels of G.A. Henty. [15] The latter, and his publishers and illustrators of course, implicitly praised the values of cruel & rampant imperialist Britain by equating these ‘virtues’ as being like the ‘natural’ sense of adventure in the shape of slim and ready boys bearing phallic symbols.

What is important to me in this is that the very act of finding the values in the possible bi-gendered / bi-sexed acts of noble speech by a ‘woman’ meant that a material penis (or the sword or gun that symbolised it) that one could envy was not compulsory or the source of validity of such emotions. Of course, it’s further complicated by the fact that we have to remember Bryher was obsessed, as she showed in the novel The Player’s Boy, with the fact that Cleopatra would in reality be represented by a young man. It would be a useful exercise to plot the move in Bryher’s two obvious literary autobiographies, based on her alter-ego Nancy, from material and biological sex/gender as the symbol of worth and worthlessness, to the understanding that sex/gender are terms that cover a range of unevenly developed and separate sex/gender characteristics. It is to the persistence of the former that gender-critical feminists claim that the claim to be ‘trans’ in ‘biological women’ (their half-baked term) is based as a psychological self-delusion.

What Bryher knew is that definitions of categories ‘boy’, ‘girl’ ‘man’ and ‘woman’ in which persons were bound to live within an undeveloped understanding of biology, sociology and psychology that failed to take into account the development of newer younger forms of interaction between these frameworks of thought. The ‘boundary of one’s horizon’ was set in too limited way thus far in history. She expresses this in her book, the sequel to Development, entitled Two Selves, thus. Eleanor has asked if things will get better for women than they were in the Second World War where girls introjected beliefs like an incapacity to even adventure as far as being NOT ‘afraid of traffic’ whilst driving. Nancy says:

“I suppose not. It is the furthest one can think through just at the present. The boundary of one’s horizon.”

Nobody is interested in freedom or development any more. There will be no money to finance any new schemes of education. As for the liberty of women! After my experience with Lady Cockle I’m beginning to fear that they will only impose fresh shackles. They squash the young more vigorously than the men.”

“It’s the old, the old in thought, rather than men or women, i imagine. Most of the girls at Downwood [her school, the experience of which formed a large chunk of the first novel], for instance, were born old. Whatever their freedom they would not have developed any further. But it is not much of an outlook”.[16]

The answer she provides is in the word development – not just personal development but development and education in the societies which provide compulsory, rather than variable and up to personal choice, meaning to empty binary categories like man/woman and boy/girl. Development in Bryher is a complex issue and this is precisely why Bryher often appears to treat boy and man, as well as girl or woman, as separated categories, all semi-independently determined rather than determined by biological development processes alone. She sees the development of maleness from boyishness as itself still a complex thing, as indeed it is. Something like this must have meant when McCabe says that: ‘H.D. and Bryher consciously defied “woman.” It is not who you love, but how you love’. She picks out in particular their ‘resistance to labelling’. [17] In the following passage moreover, McCabe summarises Bryher’s radicalism, ‘anticipating twenty-first century non-binary gender and transgenderism’, in summarising Bryher’s critical position with regard to psychoanalysis (which McCabe terms ‘ps-a’) as formulated by Freud himself in 1937, after Bryher returned from Marienbad. I find the ideas relatively underdeveloped here quite exciting for Bryher is said to have:

… formalized ps-a’s present limitations. Freud addressed an almost extinct concept, that of the ‘Victorian idea of the family’. Psychoanalysis, to survive, needed to discard the image of the Victorian family. She preferred Dr Ludwig Jekel’s idea of a band (…) alternative to hierarchical families. A main quarrel stemmed from a personal one: ps-a was blind “with regard to the girl who was really a boy,” though it “profoundly influences daily life,” anticipating twenty-first century non-binary gender and transgenderism.

Jekel was, of course, a socialist and saw psychoanalysis as aimed at social change not the maintenance of the status quo. He may also have been the cause of Bryher’s dislike of the fact that the psychoanalytic clinics ‘catered to those with money, jettisoning it “from the life, the living part”’, which required that it be affordable to ‘workers, or “badly paid intellectuals”.[18]

H.D. is not associated with this radical thought for her own part. But we cannot take any differences between them far for H.D. venerated Freud but she also venerated, as he did, contradiction, and would have been open to those exposed by Bryher. So much are both of these things so of H.D. that she could say of him, ‘but the Professor was not always right’, in the same book as she later says of a particular interpretation by Freud of one her ‘visions’: ‘Perhaps in that sense the Professor was right (actually he was always right, though we sometimes translated our thoughts into different languages or mediums)’. [19] Moreover, the reference to use of ‘different languages and mediums’ may give us pause, for translation is always difficult in H.D. texts, where rich cultural reference is often mixed with even richer personal reference to her life to which we may not be privy. Sometimes the associations are literally those of ‘madness’. McCabe in speaking of the couple’s joint analytic work on a ‘primal scene’ dream of H.D’s in Corfu in the 1920s which was projected, it appears, onto a wall, identifies it as a possible case of ‘”apophenia,” coined in 1958 by Klaus Conrad to designate “feelings of abnormal meaningfulness”’. This dream is returned to by H.D. in a letter to Bryher in 1934) in which she talks about Rodeck, the man (according to McCabe) who as the ‘“astral father”, was a smokescreen for Bryher, freeing the couple to nurture a sun-baby, or the mystic androgyne’ of that earlier vision in Corfu as interpreted by Bryher.

“He says, you had two things to hide, one that you were a girl. The other that you were a boy”. It appears I am that all-but extinct phenomena [sic.], the perfect bi’.

We should expect H.D.’s meanings here, for they concern dreams, to be rich in both reference to both the various ways in which she experienced multiple forms of past experience and to convey an intentional desire, even those she has already unearthed from the unconscious (or UNK as she termed it). Yet I baulk at McCabe’s decision to apply the term [sic.] – indicating this is an erroneous use of the word in the writer’s text itself – to this transcription of H.D. For why should the ‘perfect bi’ not be a plural group of phenomena, rather one unitary phenomenon, as McCabe guesses H.D. intended to write. After all, H.D. is addressing here her, according to McCabe, the guilt of a ‘socially trained mind’ for ‘being able to have and to be both genders’. [20] Experiencing ‘having’ both genders and ‘being’ both genders is something that is compact with multiple possibilities not just two, and certainly not just ONE, so how can the ‘perfect bi’ be just ONE phenomenon. After all each gender I have may experience the being of either of the genders in more than one way (for having any category of sex/gender differs from experiencing being that sex/gender, or, at least, so it seems to me).

We can get lost in this and we need to admit that, for, as I have already suggested, for H.D. and Bryher the experience of those labelled ‘mad’ (or labelled in any other way) is something that should not be forgotten or marginalized just because it is difficult to understand or relate to for people who consider themselves ‘normal’. I am not sure if this book will appeal to the current taste for books on the queer, for when it comes to the queerness of madness, even the most radical of thinkers tend to shut off. I try not to – for good reason in my own personal life.

All my love

Steve

[1] Susan McCabe H.D. & Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism (2021: 181) New York, Oxford University Press

[2] Susan McCabe cites ibid: 240

[3] Ibid: 18

[4] H.D. (1986: 491) from R.A.F. in the ‘Uncollected and Unpublished Poems’ (pp307 – 504) in Louis L. Martz (ed.) (1986) H.D: Collected Poems 1912 – 1944, New Directions Paperbook 611 New York, New Directions.

[5] Cited by Louis L. Martz (1986: xi, & note 2 [p.613]) ‘Introduction’ in Louis L. Martz (ed.) op.cit.: xi – xxxvi.

[6] Susan McCabe op.cit: 232

[7] H.D. (1956: 118) Tribute to Freud, New York, Pantheon Books Inc. The quotations do not necessarily follow on serially on that page

[8] H.D. (1956) op cit: 119

[9] Ibid: 120f. (…) indicates my omissions – often long passages.

[10] Bryher (2000: 39) Development (originally published 1920) in Joanne Winning (ed.) Bryher: Two Novels: Development and Two Selves Madison, USA, The University of Wisconsin Press. 21 – 177.

[11] Ibid: 37

[12] Ibid: 38

[13] Ibid: 61

[14] Ibid: 62f. The quotation cited is from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Act 5, Scene 2, 335 – 345.

[15] Susan McCabe op.cit: 35. We know Bryher did not imbibe Henty’s imperialism, although her father made much money from the Second Boer War.

[16] Bryher (2000: 247) Two Selves (originally published 1923) in Joanne Winning (ed.) Bryher: Two Novels: Development and Two Selves Madison, USA, The University of Wisconsin Press. 182 – 289.

[17] Susan McCabe op.cit: 311

[18] Ibid: 200

[19] H.D. (1956: 25 & 69 respectively) Tribute to Freud, New York, Pantheon Books Inc.

[20] Susan McCabe op.cit: 181. For UNK sees ibid: 198 (a particularly populous and packed example).

One thought on “In reporting her dream, Hilda Doolittle (known as H.D.) to her friend and lover Bryher, says: ‘It appears I am that all-but extinct phenomena [sic.], the perfect bi’.[1] This blog is based on reading Susan McCabe’s ‘bi-biography’ ‘H.D. & Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism’ (2021).”