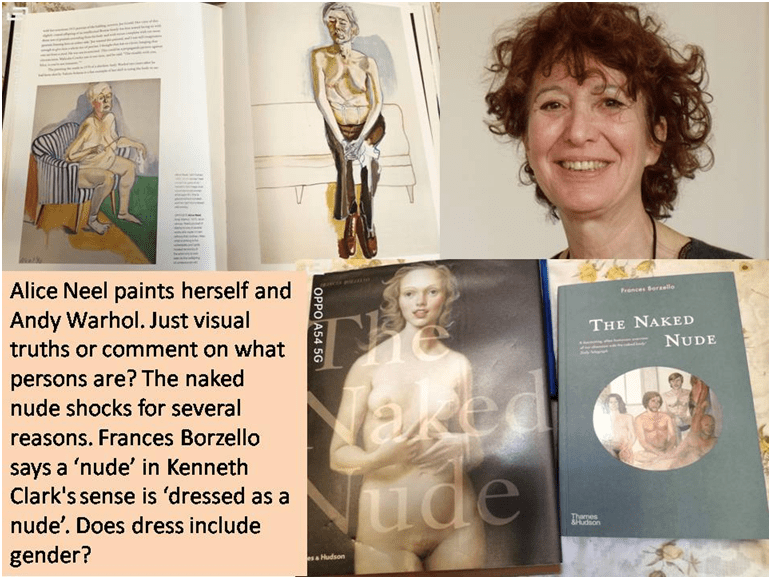

‘The new nudes ask awkward questions and behave provocatively’.[1] This blog is an act of admiration for Frances Borzello’s The Naked Nude (2012, revised 2020) London, Thames & Hudson.

Frances Borzello is an art historian and I am usually, quite frankly, antagonistic to the frameworks that define that term as an academic discipline, but sometimes a writer is able to stay within a tradition and produce something that challenges its preoccupations. This is not just because Borzello tilts at Kenneth Clark’s famous, clearly wrong-minded and elitist distinction between the naked and the nude. After all, Clark’s tottering windmill of an ‘idea’ creaked to a grinding halt long ago due to the lack of common sense, and respect for the common human and animal senses of people who like both art and life, as the wind driving its function. My respect for Borzello lies not in the studied use of distancing motifs from the ways in which artists have challenged convention, including the conventions of art history, which are evident in the discussion of ‘queer politics, and transgender politics in particular’ in the ‘Postscript’ to its new edition but rather in the adoption of the methods of critical queer theory. I regret the conventions and motifs Borzello uses in her prose. They include the usual arsenal of passive tenses and attributions of ideas that limit the claim to truth of these ideas: attributions, for instance, of radical challenges to the most challenging denials of absolutes sex/gender differences to ‘some artists and activists’, which also works associatively to typecast the ‘artists’ indicated (though not named here). [2]

However, even though I note the use of what tutors of our shallow day call ‘academic language’ (it was my bugbear teaching with other Associate Lecturers in The Open University) with dismay, I feel ‘in my gut’, as it were, that this is an academic pose of Borzello’s, whether she acknowledge that being the case or not. Why do I feel this cheeky and deeply subjective liking of Borzello despite her linguistic repertoire as a writer has any validity then? I think it is because provocative behaviour of all kinds is what is not only validated but valorised in the book. Especially the kind of provocative critique of authority which goes beyond mere ‘critical thinking’ into critical sensing – seeing, of course for this is primarily about art offered to his Majesty the Eye but also haptic sensation including those of touching, smelling, tasting, and feeling. And there is a royal road from such sensation to emotion as well as cognition, and that blending of the two such as is so reviled in some renditions of the ‘academic writing’ before mentioned. Borzello loves what shocks, though she rightly says that the ‘shock’ we may feel is a direct result of artists wishing ‘to make a break with the past as a strategy to open our eyes to difficult issues’. [3]

This summary, in the ‘Postscript’ to the revised 2020 edition, describes artists working in the ten years since the publication of this book’s first edition, yet what is new in these artists is not the use of images that shock but the elaboration of a more explicit intention behind the images in that art. Maybe this is because the broadcast of theory about the critical function of art is much more public in this period, almost as a means of filling the gap left by a public which rarely questioned the values of what can be exhibited and explored openly in public places. But if so, the change is a matter of degree in the replacement of public moral authority protected by institutions in law, and the agreed parameters of what we can see or show each other; including the way we justify that display to the senses that some call ‘critical theory’. That is certainly the effect, as explained by Borzello, of artists whose intention perhaps primarily to shock has elicited a reinterpretation of the purpose of the ‘rules of display’ (which sets the parameters of public – private behaviours and is learned by children as if they were learning not what it is correct but natural to think.

Display rules are learned in early childhood. We socialise children, for instance, by the over-determination of certain body parts as being ‘private parts’ or specialise certain spaces as private or public ones. These body parts and spaces are often those associated g with the reproductive, excremental and /or the production of pleasurable sensation from their stimulation (the erogenous zones receptors) or (and this was sometimes culturally the source of shock, the combination of any two or all three systems. A good example of those shocking mix-ups between the function of parts can be found in eighteenth century culture of wit aligned to shock. A fine example is Jonathan Swift’s display in 1732, for instance, of his knowledge that his ideal and beauteous model of female perfection in literature, Celia defecates in her private dressing room (Celia’s name is taken from Ben Jonson’s addressee in the title of his Song to Celia). The poem utilises words common in public discourse but not thought capable of use in a serious aesthetic medium like a poem. What Swift actually says is: ‘Celia shits!’

So things, which must not be expressed,

When plumped into the reeking chest,

Send up an excremental smell

To taint the parts from whence they fell.

The petticoats and gown perfume,

Which waft a stink round every room.

Thus finishing his grand survey,

Disgusted Strephon stole away

Repeating in his amorous fits,

Oh! Celia, Celia, Celia shits![4]

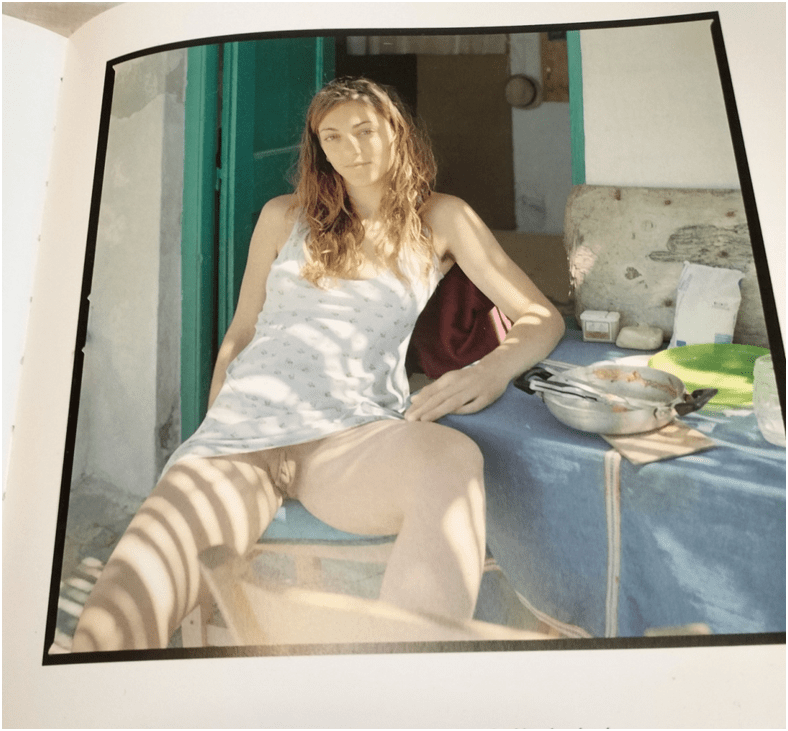

Of course, it’s all ‘common knowledge’ but the word ‘common’ is precisely the marker culturally for topics that should not be made public without consequence of typing the speaker as themselves ‘common’, as not being of a certain class. Indeed this is bourgeois culture’s display rule number one. Being ‘common’ is a putdown used to type class, gender and racial-cultural norms. These are just some of the factors that complicated the display by Panayiotis Lamprou of his photograph Portrait of my British Wife in 2011 in the National Portrait Gallery. For this wife (and how cunning of Lamprou to name her as ‘British’ as one in the eye of a nation that likes to see itself as famously reserved) sits casually at a Greek breakfast table, and, as if accidentally, displays her vagina. As Borzello writes in the text and caption respectively to her illustration of this image: ‘Our comfort with it as a portrait of a beautiful woman is disturbed by the shock of what she displays’. [5]

It is beautiful. It is ugly. It is obscene. The confused response to this work shows that when the private and public collide, we have no formula to deal with it.[6]

Likewise the worldly-wise novelist and journalist Sean O’Hagan can seem to still want to reserve the sight of a woman’s vagina to the privately imagined:

It does beg the – now quaintly old-fashioned – question, are some things better left to the imagination than the camera? Or, more pertinently, the gallery wall? [7]

But I doubt whether fascinations with visual and linguistic reserve as it is thus formulated has a long pedigree in modern history since the Renaissance. Reserve is there from early times but in part as the source of playful game that withholds delights in order to make the giving more desired when it finally comes, as in foreplay as analysed by Freud in relation to jokes. Only later does reserve (I believe though I cannot prove) need continually invigilated guardianship in the name of taste, if not morality, and possibly does not predate the late eighteenth-century in this form, with Jane Austen as a benchmark of their wider appearance. Of course, the best example of this is in the fascination with breasts in the culture of the middle-ages and onwards in Western art (in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene for instance where ‘paps’ continually surprise and divert us (or attempt thus to do). We can look at a sixteenth century visual example used in Borzello, A Lady in Her Bath (1571) by Francois Clouet:

A Lady in Her Bath is oil on wood painting by French artist, François Clouet, created in 1571. The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=149350. In Frances Borzello (2012:114, revised 2020: 121) op.cit.

This painting so very clearly wears its interest in display on its surface, whilst providing enough diverse visual material to theorise display and even ‘exposure’ in functional terms, wherein decorative exhibition is only one of those functions addressed. The use of curtains, for instance, to frame the picture and of inset portals receding from ever more private to more public space ensure we are aware of this. The exposure of the lady’s delicate breasts, which clothe her in class as much as her gold bracelets, lace headdress with pendant pearl and pearl earrings. Her gaze is indirect but clearly is aware of us, as of the other eyes that see her, including the precocious boy reaching out for fleshy fruits on the table.

Her breasts are deliberately smaller and more generously spaced relative to her torso than the two women whose breasts form a triangle with her own. One apex of the said triangle is at the breasts, squeezed together in the everyday linen she wears, of a serving maid, visually positioned next to the jug whose rotundity defines them as containers like the jug itself. The other is a servant acting as wet nurse and giving suckle to a swaddled baby, presumably of the lady’s family. This serving function ensured that that lady herself could preserve the beauty of her own breasts as otherwise ‘useless’ ornamentation. I do not know how Clouet wished us to interpret those contrasts even though I am fairly sure he offered them for that purpose.

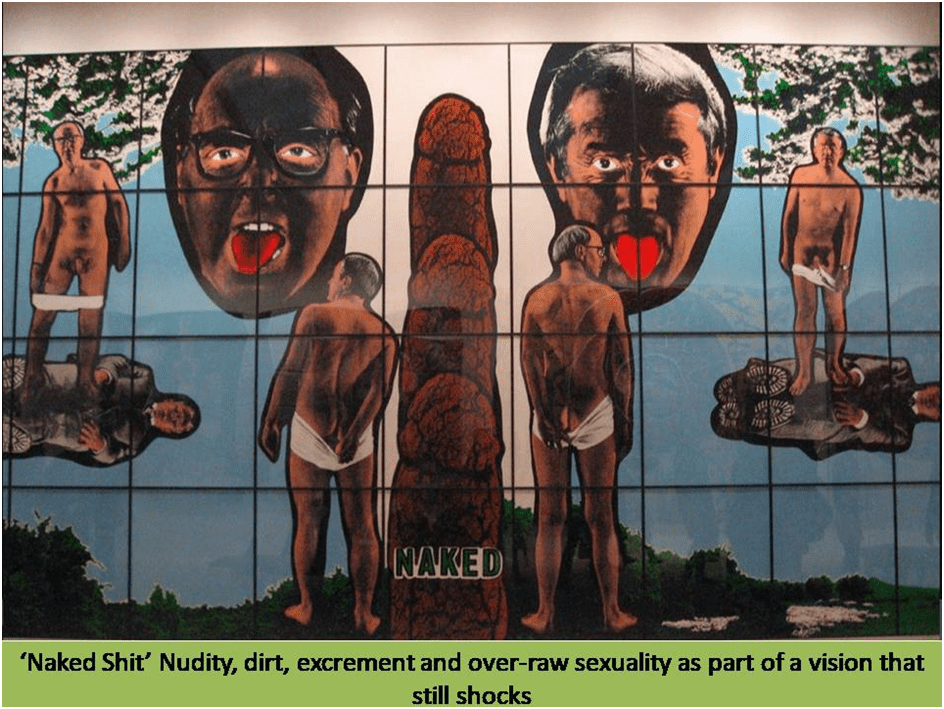

Of course, the intention to shock cannot work on an audience inured to the sight of such objects in contexts other than those of our lives in common, wherein we relax display rules because display is not the purpose of exposure of body parts. However, neither is it the purpose of the exposure of female breasts in the Clouet example above, where, if there is beauty, it serves the purpose of alerting us to the meaning of beauty in other terms than the merely aesthetic. This is, after all, how Borzello explains Gilbert & George’s huge murals which aim to make beauty of subjects considered intrinsically ugly or disgusting, like excrement both solid and fluid (subjects which ‘high’ art pretends not to reference). But Borzello is clear in stating, from the words of the artists themselves that whatever the meanings involved in this picture, they are primarily an insistence on democratic realities, especially those possessed by all – a body of some sort and its basic functions of needing to eat and evacuate waste. Working class people known to Gilbert & George do not exclude those subjects from their notice, for they are ubiquitous and refuse to use fastidious responses to make themselves appear ‘better’ (by some perverted class-based value system) than they are, which is a person in common, and as common, as other persons. As a result, the artists find beauty in the colour and biological flora and fauna of ‘piss’, as well as in that name. She says:

Gilbert & George want to reach two completely different kinds of audiences, those who think art is not for them, like the neighbourhood boys who appear in their images, as well as those who want to visit galleries. Their outrageous imagery, inspired by the young men, the sexuality and the graffiti they find around them in the East End street where they have their London home, is conveyed through repetition, overwhelming scale, limited bright colours and shiny surfaces on their art. … “We never liked the idea of the artist using a language which excludes 99% of the world’s population; we don’t think it’s necessary. That it’s only white people in London, Paris and New York in certain boroughs who would even understand the work; we think that’s so elitist and cruel to the vast general public”.[8]

Gilbert & George ‘Naked Shit’ available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/commonorgarden/392247158/

That there is something quite tongue–in-cheek in naming her chapter 7, in which this is discussed, ‘Going to Extremes’ is clear. That is because that which is considered as extreme in its capacity to shock will not always be so in the future or in different contexts. Sometimes this is the point – an image can be normalised by exposure and allow the previously forbidden to ‘be explored’, and Gilbert & George claim that this is their aim rather than confrontation. That certainly is the aim in exhibiting bodies that are, by loss of limbs or alteration of appearance from social norms, considered ‘shocking’ by those who feel they have to have art that is so aesthetic that it excludes some part of humanity – thus the interest of Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville in large overly-exposed bodies or Marc Quinn in the pregnant body of a woman, Alison Lapper, born without some body limbs. And further, the exclusion is not of people who have been marginalised, though that matters enormously, but bodies which are statistically normal and those most frequently seen in actual societies but not IDEAL. Hence the attention brought to the latter by Spenser Tunick, who uses vast numbers of naked models (volunteers from the general public) to create mass forms using the infrastructures of both land geology and human architecture, or the forensic focus of Ron Mueck hyper-real sculptures made too large or too small to pass as unnoticeable. In the later cases bodies are in some taboo circumstance but should not ‘shock’ us. Seeing you ‘Dead Dad’ may be many things, and create many emotions, but it ought not to be ‘shocking’.

Collage of work by Spenser Tunick and Ron Mueck

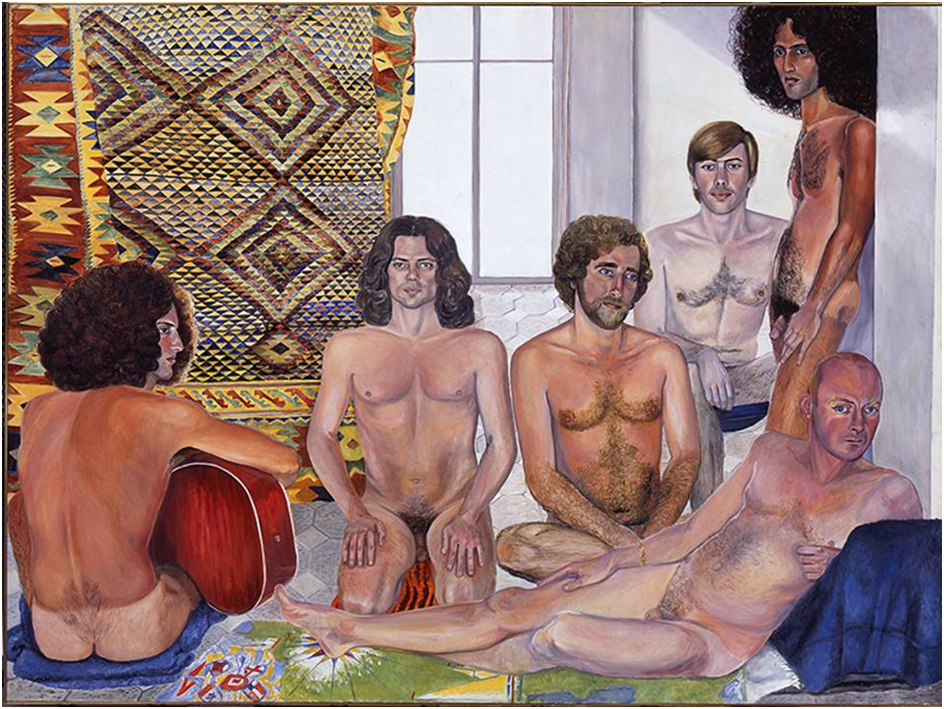

In some cases the object of an artist may be not to challenge aesthetic norms applied to art but social ones. We can see that such art dates more quickly and can fade into a merely decorative comment on the long history that seemed to favour female nudes only as the objects of male gaze. Silvia Sleigh, according to Borzello ‘reworked Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s The Turkish Bath of 1863 to produce her startling line-up of relaxed masculinity’.[9] The received wisdom about this lovely painting is that it uses real men to explore masculine naked beauty (including her own husband on the bottom right), although the main effect is to shock by the revelation of how nineteenth-century Orientalism sexualised a false notion of femininity as a plentiful luxury to be possessed by men, visually at least. Orientalism is born at the moment in history when women in the West were beginning to show their lives were neither idle nor securely supported by men who care for them, indeed rather the reverse is the truth. These men are not ‘startling’ as ‘nudes’ as such but in the proximity that they bear to each other, about which their quizzical look out to the viewer of either sex seems embarrassed and nervous. I don’t see ‘relaxation’ here as Borzello does except as a pose enacted as per direction by the artist.

The nude is still alive here rather than the naked nude despite the fact that these men have realistic variations of skin colour and body hair and bear the marks of the underwear of which they have divested themselves – not a feature of the classic nude. These men are seriously posing in ways that ape aestheticization, even if they are not there as purely beautiful but as acting it with different degrees of success. The man with pale skin at the rear with un-posed open legs is possibly the least successfully posed and hence appears as if with a gaucheness that may be considered as a characteristic of his personality. And there is personality in all of these men.

I consider the portraits of Trans’ person’s bodies by Jenny Saville in this book so good that I do not wish to speak of them, though Borzello does a very good job in this regard. I do not feel I have the language yet to meet in a satisfactory way what I think of as their radical wonder. But I do want to consider two nudes by Alice Neel, for they continue to intrigue, even though I may not have adequate language for their appreciation either.

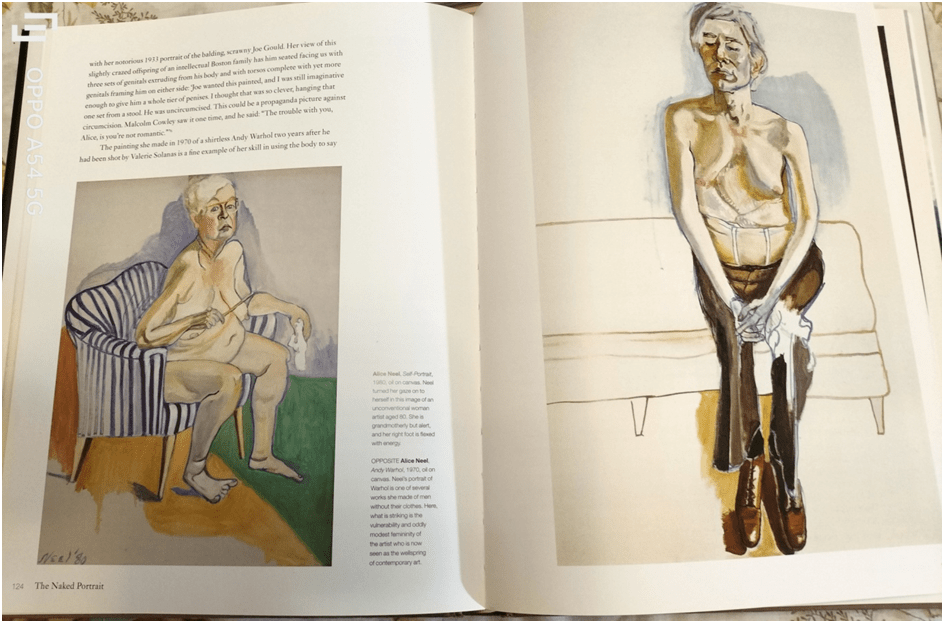

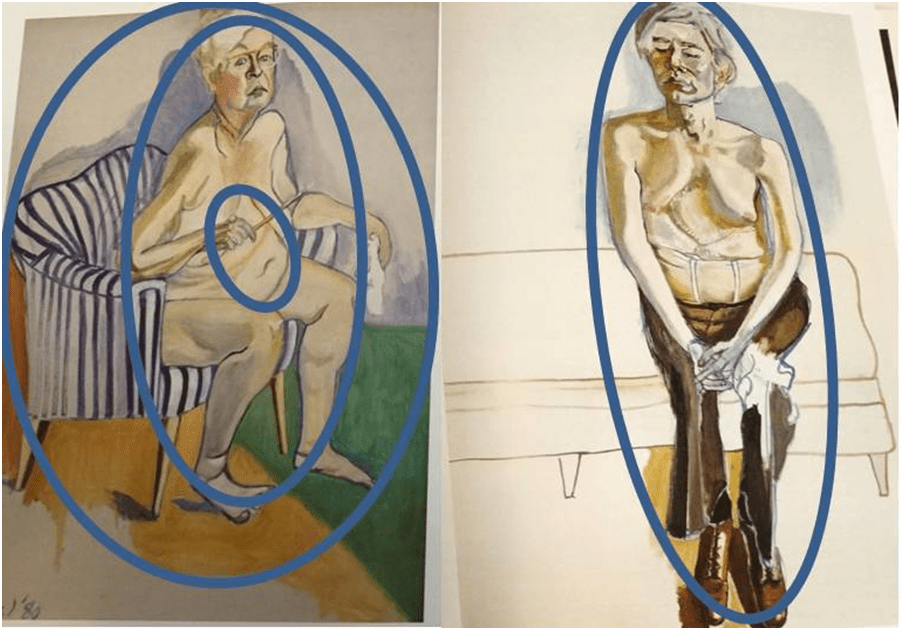

Frances Borzello’s The Naked Nude (2012:124f, pictures in revised ed.2020: 134, 136)London, Thames & Hudson. Shows Self-Portrait 1980 & Andy Warhol 1970 respectively, both by Alice Neel.

Although the two Alice Neel portraits do not appear on the same page opening in the revised edition of this book, their ease of comparison in the original edition of the book is one of its beauties. Borzello describes the portrait of Warhol, which she compares to Neel’s portrait of John Perreault (1972) to show that she could paint images of unequivocal naked masculinity. Borzello says that Neel’s version of Warhol (contrary to his public image) is ‘shocking in the almost feminine vulnerability of its soft flesh which looks as if its protective shell has been removed’. A sentence or two later, she says he ‘looks as if he has been unwrapped and his tender parts revealed’.[10]

This is a strong insight in which the painter uses strong optical tricks to convey interiority. Note, for instance, how she conveys her own strength in her self-portrait using a broadly convex shape for the figure and its containing background. The same shape is even more prominent in Warhol’s outline-shape but the effect is to indicate the mix of concave and convex shapes which define Warhol’s body within that outline, which so contrasts with the healthy ubiquity of rotundity inside Neel’s own self-image. It is a rotundity that shapes even her sagging breasts, so that her aged flesh seems almost renascent. Warhol’s torso is described by concave shapes that are formed by the linear definition of his sagging beast (in contrast to those of Neel), the shapes rounded out by his Y-front underpants and the scar wound of his operation following his shooting by Valerie Solanas. The concave shape defined too by the way he holds his hands make the interior of the lines they form look as if his skin cover ages beneath the picture surface, aided by deep internalising shading.

This makes an analogy between the interiority of consciousness implied by his shut eyes and shaded face and the sense of a physical recession of the body into the centre of his torso. In my own view I think it is less important to see this as symbolising Warhol’s femininity, as Borzello suggests, as the lack of health revealed by the man’s intuited response to his own aging compared to hers. Her self-portrait may shows the truths of aging but, as Borzello says, the effect of the whole bright and blooming portrait (including the health rotund cheeks) shows ‘an abandon of light, bright colours that one would expect in a painting of spring’. The artist’s lives can indeed be usefully compared in this way, though my view of Warhol may be over-dark and based on the sense of self-oppression I feel in his sexual self-image.

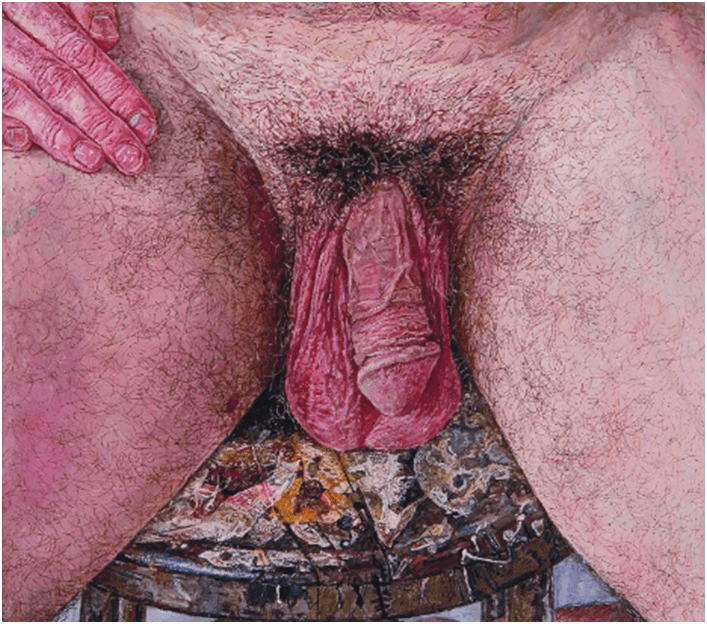

If anything could, my response to Borzello, and gratitude for her insight, is based on the ease she creates by her own defence of the validity of subjectivity in the evaluation of art in a viewer. It allows me to reinterpret in slight ways her own interpretations to meet my own perception of things, including pictures, just as it would any other viewer, ready to respond and discuss why they respond thus. There is so much openness in this book and its concepts that I could lengthen this piece forever, but I won’t. I want to end with the discussion of a key difference between the nude, on the one hand, and the naked nude, on the other, that emerges strongly in the book’s treatment of Ellen Altfest’s The Penis (2006). Borzello writes that this painting ‘’illustrates the change from Clark’s notion of the nude as “the body re-formed for art”’. For the body for Altfest speaks through realistic detail such that a body part speaks for the whole man without him being there visually otherwise detail:

Every infinitesimally small hair is delineated rising free of the skin, and every fold and wrinkle is suggestive of weight and mass. Neither medical illustration nor genitals tidied up for art, this is in fact a portrait of a penis.[11]

Ellen Altfest (2006) oil on canvas

I think this in some way minimises what happens here. Patriarchy has always rested on idealised symbols of the phallus, sometimes in hidden forms in art and architecture, suggestive of power appropriate to masculine authority in such societies (I will leave this generalisation to speak for itself; coward that I am, though I think it can be illustrated effectively). In art this tendency includes different ways in which the penis is appropriate to the power of its purpose – whether in perfectly proportioned but small penis of the classical nude in Greek art or the larger ones of the Herm or the Priapus representing male hegemony over fertility in Greek and Roman thought respectively. While the phallus retains its content of patriarchal power hidden in the artist’s intentions, it partakes of the classical focus on idealized male authority I’d argue, and this remains one of my main disagreements, I think, with Borzello. I’d state the area of disagreement thus. She makes much in her fifth chapter of a supposed discrepancy between idealisation of the nude and the practice of portraiture of real people. One example she uses is Agnolo Bronzino’s c.1530 portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune. Of this she writes (in the caption to the picture itself) that it:

… sums up the problem of allying the portrait with the nude. The ideal nude presented generalized perfection, while the portrait, even when ‘improved’ for art, could never skimp on the individuality of the sitter’s appearance.[12]

The thesis seems to me here to revert to classic art historical formulations, rather than (as Borzello usually does) describing what is seen and its effect. Borzello does not say why detail of Andrea Doria’s body and face conflicts with the ideal. I think it does not. For, as with most allegoric art of the sixteenth century meaning could be layered so that the reference to a real admiral of the mighty Genoese navy works in concert with the ideal of the divine Roman ruler of the sea, Neptune. And the individual is thus idealized in his particularity. After all this is not really a body that lacks significant and appropriate idealisation. It is the very image I would say of an idealised potency, all the more powerful in the body of older but vibrant flesh conveyed, if more plentiful than might be shown in an idealised young man.

Agnolo Bronzino’s c.1530 portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune. Available at: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/547468898423909850/

The sunken midline of the torso which dominates the picture’s centre repeats the upward direction of other symbols of power present, such as the trident with its thick shaft. Likewise, the girth of the pillar against which Andrea stands and on which his name is represented as carved in gold symbolises maritime power. And this symbolism rest on a hidden secret, curled within the flowing linen that backgrounds the man and which he holds up against his sexual organ. No-one looking at this painting, though only schoolboys, other than myself, will in all probability comment thereon, cannot see that the curtain held against him to hide his lower body still reveals the beginnings of the shaft of Neptune’s penis, caught in the light that penetrates the gap between body and the held curtain and the more visible because of the darker presence of the idealised pubic hair shadow above it. This is more thorough idealisation the more potent because it represents a patriarch – a god-cum-father potent in sex as in valour, who might represent not only the ideal man for the job but the ideal of the basis of Genoese state power – military and mercantile potency on the sea (the two kinds of potency flowing into each other) for the ideal has to merge with the real if it is to be politically potent in the warring Italian states. It is this hidden allegory that is represented by the nearly hidden phallus of which Andrea’s body and the ship’s central column become the symbol.

Borzello argues that sculpture gave up on idealisation long after painting. Brancusi’s Torso of a Young Man II (1923) is given more leeway for a kind of radicalism than Henry Moore in this respect. She says of it that:

Abstraction had a huge effect on the presentation of the nude … Brancusi’s pared-down nudes retain only vestigial traces of gender. The apparently female nature of this torso is counteracted by its phallic upthrust.[13]

Constantin Brancusi’s Torso of a Young Man II (1923). Available at: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/99360735513411231/

I have to admit that I don’t see anything ‘apparently female’ in this piece, other than the absence of a penis in the piece conceived as a realistic torso. The rounded curvature of the piece is not intrinsically female (as it is not in Andrea Doria). And as in Andrea Doria, the phallus and gonads have become the entire structure of the male torso. This supports Borzello’s overall thesis in Chapter 1 but does not rescue Brancusi from her less supportive view of Henry Moore. The fact is that bad ideology too often produces great beauty sometimes – hence its danger.

In both cases above however, my disagreements with Borzello are less significant than my admiration of her approach through invoking a viewer’s responsiveness to what is seen and her overall thesis. For, as in her discussion of Altfest’s The Penis, it is clear that Borzello is correct in indicating that the ‘classical’ male nude portrait, being already in some form an idealization is antagonistic to unclothing the reality of the penis as a physical mass of skin-covered flesh that is not ever anything like what patriarchy wants to believe it is. It is always less acceptable in such realism; an idea we see in the penis formed of excrement in the Gilbert & George Naked Shit example above. The new nude forces a complex re-formulation of the penis as an idea.

With this, and perhaps with no real conclusion, I will end. Do read this lovely book.

All my love

Steve

[1] Frances Borzello’s The Naked Nude (2012:11, revised & 2020: 12)London, Thames & Hudson

[2] Frances Borzello’s The Naked Nude (2020: 202)London, Thames & Hudson

[3] Ibid: 207

[4] Jonathan Swift The Lady’s Dressing Room available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50579/the-ladys-dressing-room

[5] Frances Borzello (2012:137, revised 2020: 149) op.cit.

[6] Ibid: 2012: 136, revised 2020: 148)

[7] Sean O’Hagan (2010) ‘Panayiotis Lamprou: the casual power of an intimate portrait’ in The Guardian Online (Fri 17 Sep 2010 17.54 BST)

[8] Frances Borzello (2012:170f, revised 2020: 181) op.cit.

[9] [9] ibid: 2012:122f., revised 2020: 130.

[10] ibid: 2012:126., revised 2020: 135

[11] ibid: 2012:174., revised 2020: 187

[12] ibid: 2012:110., revised 2020: 116

[13] ibid: 2012:32., revised 2020: 33