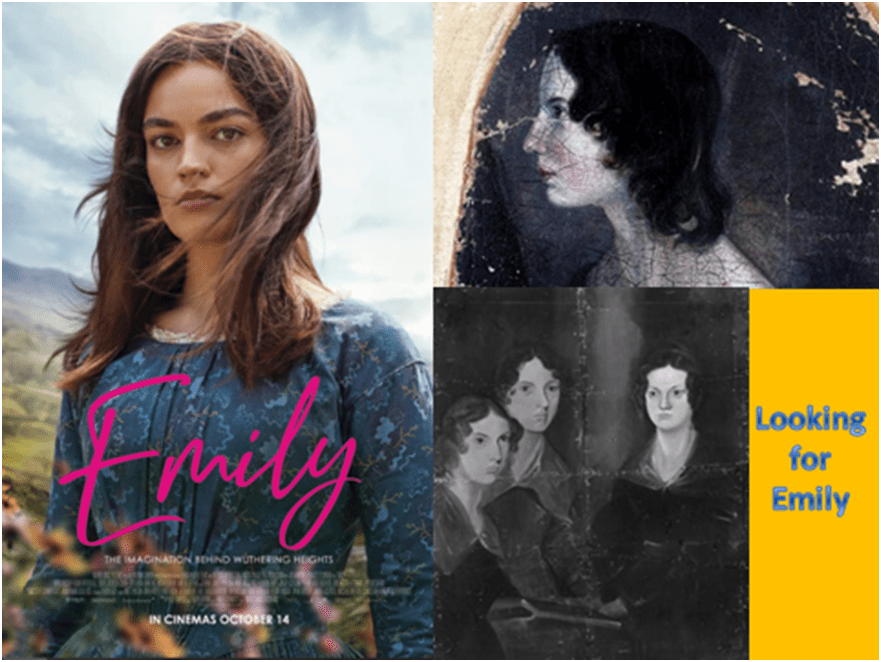

True stories about strange lives: comparing views about truth-telling and ‘explanations for female genius’, from some of the film critics of Frances O’Connor’s Emily. I saw this film on Sunday 16th October of the Odeon in Durham.

In The Sunday Times, Tom Shone takes a severe view of the duty of a film that looks like a biopic to tell the truth and, in this regard, he retells the story that is conveyed in the film in order to undermine with ONE, but a very weighty ONE, objection:

There’s only one problem with all this: it didn’t happen. Not one iota of it. Anne was the Brontë infatuated with [her father’s new curate, William] Weightman. Emily treated him with disdain. Moreover, Wuthering Heights is clearly the work of someone who has never had an erotic relationship. You can tell because the sex is everywhere – between the brothers and sisters, in the landscape, beyond the grave – except between the two consenting live adults. So what do we gain by pretending otherwise?[1]

It ought to give us pause as we read this that there is so little modesty in the large claims made, especially the hint for seeing clearly the symptoms of sexual frustration in young women – namely that they see ‘sex everywhere’ but where it might be reasonably found – with a living adult who consents to that sex. There is no justification for saying Emily had ‘never had an erotic relationship’ in any of this speculation about a literary work. After all the very same factors are true of Bram Stoker’s Dracula but people rarely claim that such features of that fiction, with its blend of subjective fantasy and personal accounts in diaries make it ‘clearly’ the case that Stoker never had an erotic relationship. That may be in fact because biographical details implying this fact exist and that it is still absolutely not the case that the features of a literary work can ever lead to any sure conclusion about the details of its author’s life.

Radheyan Simonpillai reviewing the film’s airing at the Toronto Film Festival for The Guardian takes a much more grounded view of the links between literary works and the author’s biography:

Emily is the kind of origin story that imagines antecedents in Brontë’s life to elements of her novel, like a passionate affair or a bitter rivalry – given the subject, these things can go hand in hand. Using the fictional narrative in Wuthering Heights as a window into Brontë is inevitable for any kind of biography since so little is known about the author. Most biographical details are filtered through Charlotte’s voice, published in biographies of the Jane Eyre author, which O’Connor understandably treats as suspect. Her film imagines a petty rivalry between the siblings. She depicts Charlotte (Alexandra Dowling) as a loving sister but one whose affection can often verge on patronizing.

Rigid historians will have a field day with this and the other guesswork in the film, like Brontë’s leisurely opium use and the central illicit affair she has with William Weightman, a parish curate who lived in the family’s home for a few years. Maybe this affair never happened. If it did, who would ever write about it? In any case, the way O’Connor pairs them together just feels right.[2]

I do not cite the last in order to characterise Shone as one of the ‘rigid historians’ mentioned by Simonpillai, but the judgement of these putative ‘rigid historians’ is the same as the unhistorical musings of the Gradgrind type in Shone. For the truth of the matter with regard to Emily Brontë’s biography is as described by Simonpillai. And, as in the cases where queer sexuality has to be inferred from a work (the case of Whitman for instance which openly queer modern poet Mark Doty has discussed using the theoretical work of José Esteban Muñoz – use this link for my blog on Doty’s views of Whitman), extant biography often presumes bias to heterosexuality or, in the case of unmarried young women, pre-sexual-being rather than err on the basis of presumed links between life and work. Nothing in Wuthering Heights confirms or denies that Emily experienced a physical sexual relationship, but much presumes that Emily wished her readers to understand the complexity with which sex often inserts into all relationships; imagined, realised or, as in all likelihood, and like most recounted relationships, a combination of the two.

I cannot say with Simonpillai that the pairing of Weightman and Emily ‘just feels right’, but it does chime with some aspects of how the writer must have seen the accidents and metamorphoses that shape the sexual objects chosen by young people, and their link to the imagination. Clearly Francis O’Connor has never claimed the story to be a true one, and, of course, biopics rarely are: “In creating an imagined life for Emily, she will live again for our audience,” she says in fact. When Shone says that Weightman ‘took her’ (Emily that is) ‘on the floor of an abandoned cottage’, he misses some of the intention of the film in linking this imagined affair to Emily’s great novel, for what he calls an ‘abandoned cottage’ is surely ‘Top Withens’, the abandoned house on which the Earnshaw domicile ‘Wuthering Heights’ is based in the book entitled Wuthering Heights. The real location bears no resemblance to the house described but as Frances O’Connor says, to get the feel of what you want to achieve a writer has, as she herself did with the film’s screenplay, ‘let the imagination run wild’. And this is the feel of the film, which is as much about a writer’s imagined recreation of ideas like ‘freedom in thought’ (the phrase Emily in the film only has tattooed on her arm in order to copy her brother Branwell and which phrase both shout out aloud, where no-one but sheep may hear their broadcast on the Yorkshire moors above Haworth.

There are other deviations from fact. Being a literary bore myself, the one that peeved me most, if not for long or for real, was that noticed by Peter Bradshaw previewing the film for The Guardian. He says: ‘incidentally, the published copy of Wuthering Heights which Emily finally holds in her hands would not have been credited to “Emily Brontë” but “Ellis Bell”, because of the patriarchal world of publishing’.[3] But do we expect a biopic to clarify this matter? I think had it tried to do so, it would have been a distraction to anyone not yet introduced to the writer to explain the reasons for that nom deplume – one of a set of related curates invented by all three sisters (the other two were Currer Bell [for Charlotte] and Acton Bell [for Anne]) to cover up their gender

Similarly the cusp between imagined sex and physical engagement in it is no longer so rigidly opaque and thick as it would be for the Brontës and this ‘fact’ (itself often really based on assumptions about women of the past rather than fact alone) is not helpfully explained, when the true object of a writer is to show Emily as transgressive of conventional life. Enjoying the novel does not depend on a clear vision of the moral landscape of Victorian Yorkshire, and (besides) such visions are themselves often contestable on many grounds. Bradshaw states the case for Frances O’Connor most empathetically: ‘This is a sensually imaginative dive into the life of the Wuthering Heights author: it is a real passion project for O’Connor, with some wonderfully arresting insights’.[4]

This convinces me for we can no more say the story in the tale is untrue than true, even though evidence exists that Emily said at some point that she despised Curate Weightman and that much in Wuthering Heights is an imaginary exercise rather than autobiographical in any direct way. As Bradshaw says, it is also true that: ‘In real life, the small matter of contraception or the lack of it might have made itself felt in the case of Emily and William’s grand passion’. But even here, we may miss the nuance of sex before the availability of accessible contraception.

And the film is not only about this sexual relationship or an attempt to say that its ‘explanation for female genius’ is ‘a man dunnit’; the conclusion Tom Shone extrapolates from the film. In fact the film does more with the references to alcohol, drugs and sex than insert them as a modern element for an old story. They were a part of Branwell’s life, and all of his sisters were aware of that fact and variously reflected these elements in their fictions dispersed between very different characters. The role of opium in the life of women inclined to illness was more open than we imagine. There are worse things than getting the wrong idea about what Emily was like in truth, one being never contacting her genius at all, especially the beautiful, sensual and wild longing in her poetry, which is as important in the film as Wuthering Heights and more present than that novel except for its locations.

Come, the wind may never again

Blow as now it blows for us;

And the stars may never again shine as now they shine;

Long before October returns,

Seas of blood will have parted us;

And you must crush the love in your heart, and I the love in mine![5]

The strangeness of that reference in this poem to ‘seas of blood’ may resonate with readers who have seen this film. Shone fears that they might imagine it referred to a real erotic relationship but would that be so heinous. We just don’t know what exactly sparked her imagination that this poem contains of an invitation to someone to come closer to her before the opportunity goes the way of all temporal things. It is as much a poem about the flight of time and the necessity of seizing the moment as Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress or Browning’s Two in the Campagna and, as potentially as full of sexual charge. But no, says Shone. Shone prefers the Emily in Sally Wainwright’s film of 2016. That, no doubt is a fine image of Emily but will no less be a thing of imagination. Of a ‘distant historical personage about which surprisingly little is known’ as Shone admits Emily is. There will, for that reason, be many imagined versions and that to pretend that we might ever attain a true and certain picture is fanciful.

Meanwhile like me, enjoy this film. And enjoy scenes like this picked out by Bradshaw below, which, in my opinion at least, has little to do with sex but much to do with the feminist vision of this film and its determination to place the sexual and the Gothic in the same family relation (in more than one sense) within that vision and attempt to make some sense of it. It is a scene that brilliantly evokes the ghostly opening of Wuthering Heights and Lockwood’s vision of the cruel exclusion of Cathy from the social world and the reason he replicates, with much visceral violence, that exclusion without being at all similar. Bradshaw describes it thus:

Most strikingly of all, O’Connor expresses all of the sisters’ imaginative life in the mask that Patrick did own in real life, encouraging role-play games. Emily uses it to channel the spirit of their departed, longed-for mother; it is a disturbing, séance-like scene that hints at something unearthly and occult in her creativity and perhaps all creativity. Had he lived to see it, this is a movie scene that I think Yorkshireman Ted Hughes would have loved. It is a real achievement for O’Connor.

All my love

Steve

[1] Tom Shone (2022: 15) ‘Sex, Drugs and Emily’, The Sunday Times Culture insert (16 October 2022, 14f.

[2]Radheyan Simonpillai (2022) ‘Sensitive Brontë biopic is a thrillingly unconventional watch’ in The Guardian (online) Sat 10 Sep 2022 04.30 BST

[3]Peter Bradshaw (2022) ‘Love, passion and sex in impressive Brontë biopic’ in The Guardian (Wed 12 Oct 2022 13.26 BST)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50536/silent-is-the-house