‘The biggest task of the show is the actress playing Nora’s (sic.). … A more selfish actress would make the whole play about herself, but not Hannah [Ellis Ryan]. For her it’s very much an ensemble. Michael Meyer, the translator, always used to say that actors who want to grandstand, who aren’t willing to play relationships, always fail with Ibsen, because what fascinated him was the complexity of relationships’. [1] This blog discusses the production of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (Michael Meyer translation) by Elysium Theatre Company played on 14th October at Bishop Auckland Town Hall. References to text (not in all precise respects like the production adapted one) from Henrik Ibsen (translated Michael Meyer) [1990: 23 – 104] Plays: Two (A Doll’s House, An Enemy of the People, Hedda Gabler) published in London by Methuen Drama.

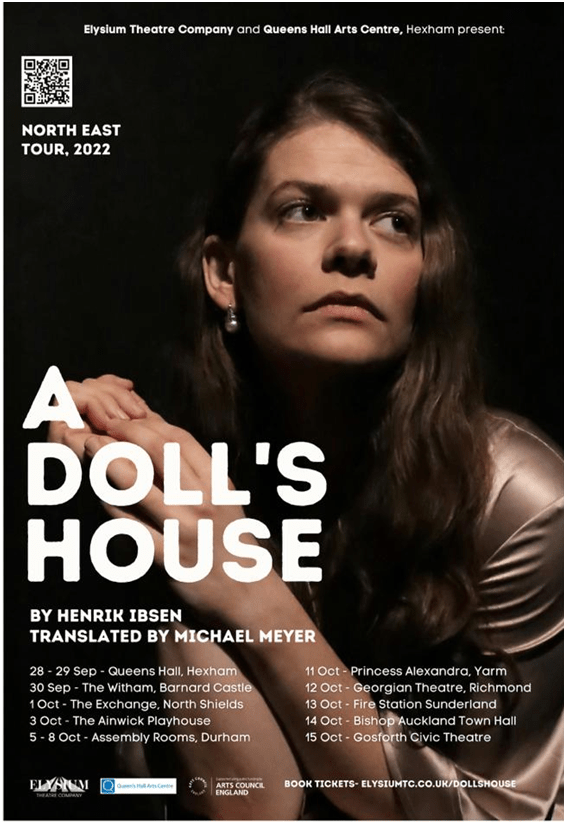

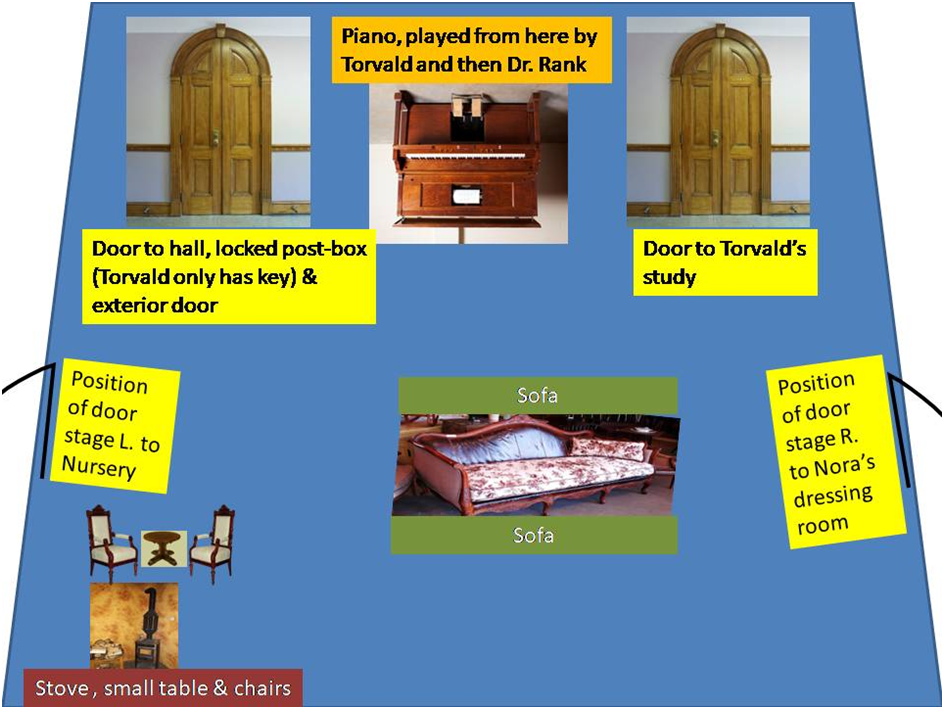

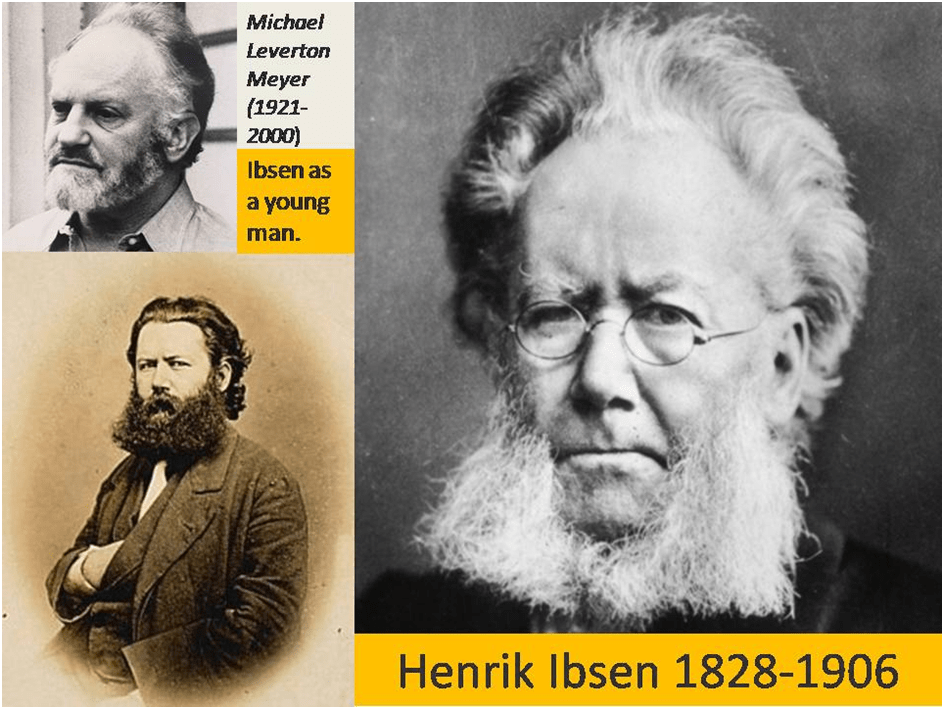

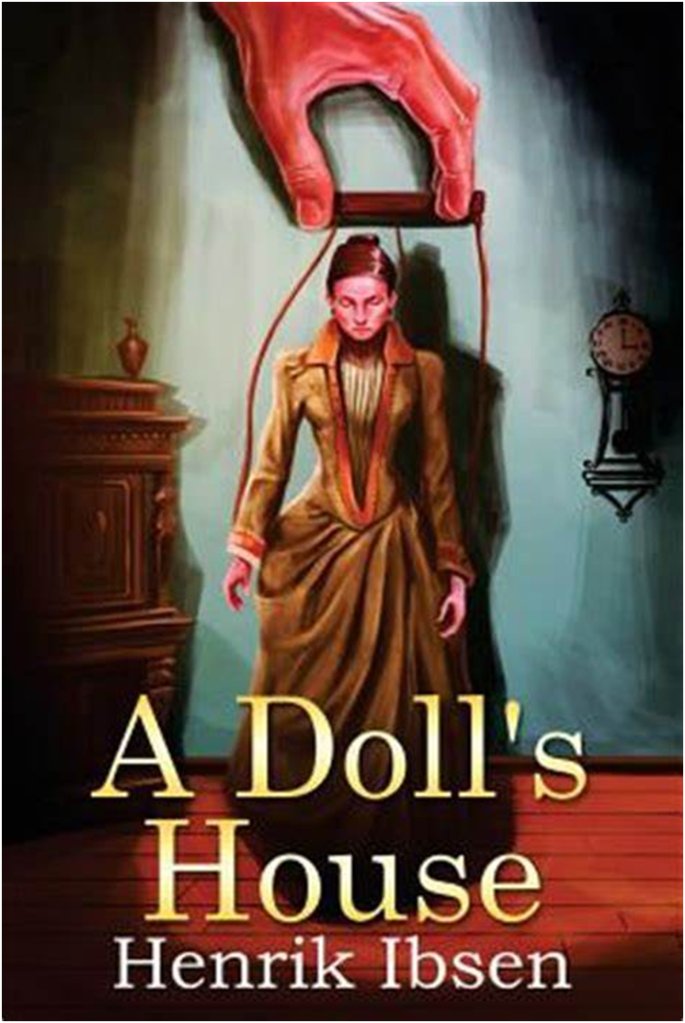

This is a blog based upon a difference of opinion between myself and best friend, Justin Curley, after seeing this production of a play neither of us had pre-read. The production does not use child-actors (or any other visibly embodied substitute) to represent the children of Nora Helmer, for whom Ibsen had written a brief role in his play. Instead, the voices of the children-at-play were taped and heard by the audience before the play opened. They formed thus a kind of sub-textual experience that was only apparent in parts of the original play where the children are often said to be playing in a nursery next to the ‘comfortably and tastefully, but not expensively furnished room’ represented in the play and its only scene but behind a closed door stage-left.[2] The only words I remember as being audible on the tape that I read also in the text are these: Will you play with us again, now? … Oh but, Mummy, you promised!’[3] These phrases resonated with me. Clearly, they had also resonated with the cast of the Elysium Theatre production and, as they say in their blog, they discussed together, early in the rehearsal process; ‘the whole issue of motherhood and the differing perspectives women can have on that’. [4]

I thought originally, and shared this opinion with Geoff, my husband, and Justin, that this play took its lead from Euripides Medea, which all three of us had seen at the Edinburgh Festival. My point was, I think, that in both cases the role of women in relation to how a current marriage is brought to a practical end is made problematic in relation to the existence, and subsequent fate, of the children of that marriage, BUT mainly for the woman not the man. In Medea the chorus of Theban women frequently raise this issue with Medea herself. So much is this so that Medea herself sees no other way of showing her special relationship to her children, in contrast to that with their father, Jason, other than murdering them. A discussion followed because Justin felt that this theme cannot be traced to literary allusion nor inheritance of a tradition in the history of drama but rather is a reflection of discourse about the subordinated position of women in both periods of history, geography and culture that is only accidentally the same because of similarities in the patriarchal organisation of society in each.

I now agree with him and accept that formulation. But the difference of view did stimulate me to read the Meyer text in order to see if there was room for interesting comparisons of the plays of any kind. Now I tend to think, even if here that view was over-determined by the clarity of Justin’s expression of it, looking to literary influences rather impoverishes the amazing cleverness of the theatrical achievement of this play. For instance, the sound of children-at-play on the recorded piece used in the production biased us to see the handling of the idea of Nora seeking her independence as a behaviour that is capable of being perceived by some as an example of that of a morally irresponsible mother. I think this sub-story of the fate of Nora and Torvald’s children would be interpreted very differently, with regard to Nora in particular, if the short-time visible presence of the children playing with each other had occurred in the production as is suggested it should in the text itself.

For instance, Ibsen validates in his text the fact that we only hear certain bits of the children’ speech as in the audible recording in this production – other parts being represented in stage directions like these two: ‘The children answer her inaudibly as she talks to them …. Nora takes off the children’s outdoor clothes and throws them anywhere while they all chatter simultaneously’.[5] The reduction of child voices in concert to incomprehensible chatter is clearly motivated in the text. In the Elysium Theatre production’s use of recorded voice passages, not being able to hear the children’s voice could be attributed to faulty equipment or to the lack of full audience attention (including one’s own) to bits of the play heard only in a medium usually thought of as non-theatrical. I think for me this was the case until I reflected on reading the text as well. In reading the play, we see other ways of interpreting what occurs.

Indeed, in as much as the children’s talk has content in our first sight of them it is that translated from their ‘chatter’ by Nora into remarks like ‘dogs don’t bite lovely little baby dolls’. This kind of nonsensical baby-talk is possibly that of the children but exists only as interpreted by the mother, such that her input into it may rob it of the intention of the child’s own communication. I see it as motivated by the fear of the external world, represented by ‘big dogs’, that arises from their vulnerability. Nora, in the manner of adults generally, converts the anxious, fearful and vulnerable in child-talk into a kind of nonsense which the adults understand to be all that children are capable of speaking or to contain the overwhelming nature of its emotional charge, in the interests of the child or their carer. Even more so, adults fear the openness and lack of restrained control of children’s talk with its ‘insensitivity’ to the need in adults to keep secrets or operate with reserve with each other. There is a fine example in the play which shows the kind of complex mixed motivations of adult life that are not as much about the ‘character’ of a single actor but the manner in which persons perform adult relationships.

Invaded by Krogstad’s needs to restore his own adult respectability by using evidence of her past behaviour (she forged her dying father’s signature as guarantor on an I.O.U. proffered to Krogstadt for a loan), she sends the children into the nursery stage left to ‘play’. Nora’s soliloquised examination of her own mixed motives for her past action and thoughts of its possible consequences are interrupted by the children now standing at the supposed nursery doorway at stage left.

NORA … What nonsense! He’s trying to frighten me! I’m not that stupid. (Busies herself gathering together the children’s clothes; then she suddenly stops.) But – ? No, it’s impossible. I did it for love, didn’t I?

CHILDREN (in the doorway, left) Mummy, the strange gentleman has gone out into the street.

NORA: Yes, yes, I know. But don’t talk to anyone about the strange gentleman. You hear? Not even to Daddy.

CHILDREN: No, Mummy. Will you play with us again now?

NORA: No, no. Not now.

CHTLDREN: Oh but Mummy you promised!

NORA: I know, but I can’t just now. Go back to the nursery. I’ve a lot to do. Go away, my darlings, go away.

She pushes them gently into the other room, and closes the door behind them.[6]

Nora treats the children with unreserved contempt for plain truth. She is not too busy though she is preoccupied. She nominates her children ‘darlings’, but her direct imperative (Go away!) ushers them out of her sight with a ‘push’, however ‘gentle’ that physical expulsion is. Any softening of our explanation here of Nora’s behaviour will rely on the perceived permissions to which adults often feel themselves to be entitled to treat children as of lesser moral worth than another adult (at least one of the same class, ‘race’, language, culture or gender), based on rationalisations of their lack of understanding or development. These elements in the manner most adults use to ‘relate’ to children shows us how Ibsen understands human action and acting is an almost pre-scripted demonstration of the deep structural aspects of all relationships based on relative power; and the shifts of regard this entitles in organised and hierarchical societies.

And in fact the ‘adult – child relationship’ is a useful model for other ways in which entitled persons invalidate the content of the words and actions of others, especially those persons who can easily be ‘othered’. Lajos Brons in 2015 defined ‘othering’ thus:

Othering is the construction and identification of the self or in-group and the other or out-group in mutual, unequal opposition by attributing relative inferiority and/or radical alienness to the other/out-group. The notion of othering spread from feminist theory and post-colonial studies to other areas of the humanities and social sciences, but is originally rooted in Hegel’s dialectic of identification and distantiation in the encounter of the self with some other in his “Master-Slave dialectic”.[7]

Of course, such a cognitive construct is nuanced in its practical application. Thus, psychodynamic analysts call the ways in which the expression of what might be overwhelmingly negative and fearful in the child’s consciousness is deflected by means of undermining the validity of their emotion as a form of ‘holding’ or ‘containing’ that overwhelming content for the child by the adult carer. I see this manner of translating people in ways that reduce their behaviour to a kind of performed nonsense as being vital to the play. It is after all precisely how Torvald Helmer behaves to his wife, in the manner of a patriarchal husband; nominating her, and treating her as, a ‘child’ But Ibsen is not I think making this an example of the specific deficiencies of Torvald’s, or even of all men’s, ‘character’ but rather is pointing to a pre-scripted means of relationship within heterosexual marriage that is no more personal in its character than the way Nora uses power she believes to be legitimate in ‘othering’ her own children. Indeed, by the end of the play she can tell her husband that ‘our home has never been anything but a playroom’. [8]

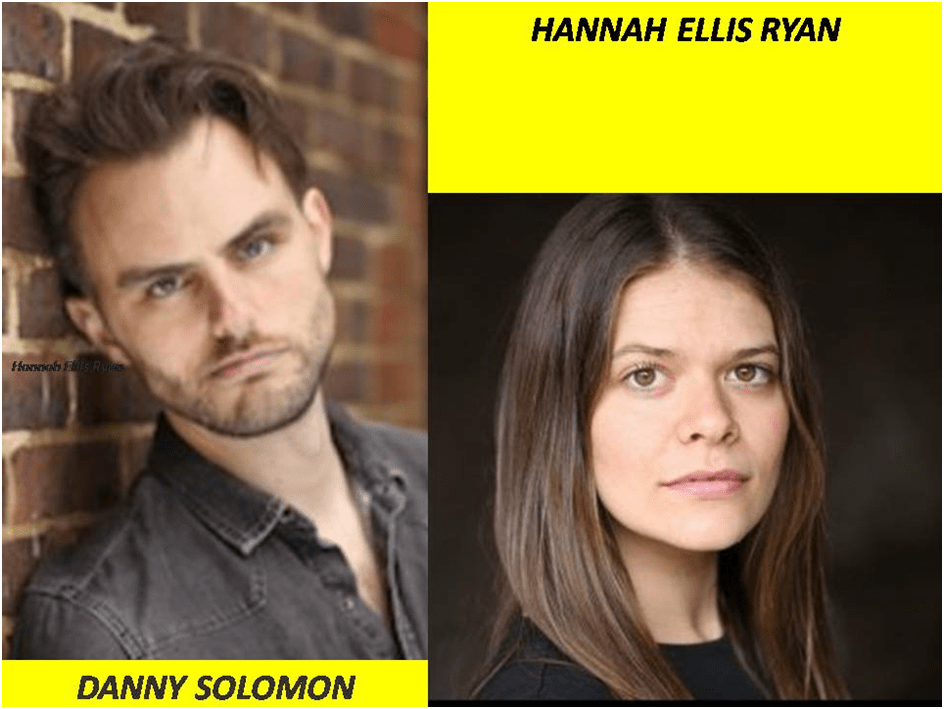

Moreover, Danny Solomon and Hannah Ellis Ryan as actors were clearly not just playing ‘characters’ but also using the cast ensemble to show how conventionally described relationships, such as marriage, shape and are shaped by social contexts. These contexts include the specific physical manifestation of more general contexts in the concrete form of room settings, the placing of items of furniture and barriers between external and internal worlds (most notably those represented by doors opening and shutting), dressing up in costume and the clothes appropriate to diverse contexts as well as responding in ‘appropriate (that is, pre-scripted) ways to the class and type of other individuals, and the play of relationships indicated by the spaces manipulate between persons – their proxemics. For relationships are complex because the roles we play in them have inequalities in relation to each other that determine our actions as surely as does what we call personality. For this complexity in social life, theatrical relationships are themselves a metaphor – including the facts that, on the one hand, how we are dressed can be determined often by another (a fact made plain by Torvald’s choice of a costume for Nora to appear in when dancing the tarantella at a party), and, on the other, how some of our actions are also consciously directed by a more powerful significant other (as parents do to children) rather than by ourselves autonomously. The preparations for the tarantella dance make this point directly – Torvald resigning the playing of the music to Dr. Rank so that he can more forcefully ‘direct’ her actions like a show’s director. He shouts at her to act ‘Slower! Slower!’ and ‘Not so violently’, only to find that she does not listen and that he must find a manner in which it will ‘be easier for (him) to show her’ how to act.[9]

However, the irony of this is important to Ibsen. It, of course, shows Torvald’s immense desire to have power over Nora, especially in the regulation of her femininity and her willingness to collude with his right to control, sometimes fully but sometimes only apparently. The collusion is apparent, rather than real, for instance, in the case of the tarantella rehearsal, for when she says: ‘Correct me, lead me, the way you always do’, she is in fact controlling his actions in making it impossible for him, at this moment at least, to go ‘to see if any letters have come’ and thus find the letter of Krogstad’s that compromises her.[10]

Moreover, this scene plays with characteristic images of women that veer between, on one hand, the ‘angel in the house’, a common nineteenth-century bourgeois trope that describes the perfect woman and, on the other, the fantastical version of the dangerously playful woman, whom so easily can be seen too (when her fantasies outstrip the desire for a patriarchal ordering of things) as the destabilising whore. Nora in Act 1 says to Torvald: ‘I’ll sing for you, dance for you’. [11] She explains to Mrs Linde that: ‘There’s going to be a fancy-dress ball tomorrow night upstairs at Consul Stenborg’s and Torvald wants me to go as a Neapolitan fisher-girl and dance the tarantella’. [12] Yet when at the end of Act 2 she rehearses the tarantella for Torvald, he is clearly disturbed at the violence of her fantasies. She, moreover, in the classic image of the repressed woman becomes a more autonomously sexualised force threatening Torvald like a siren, losing control of her hair so that its looseness unconsciously symbolises for Torvald the contradictions of his desires with respect for her – to be playful enough to look like a sexually fantasised being without escaping male regulation in doing so:

HELMER has stationed himself by the stove and tries repeatedly to correct her, but she seems not to hear him. Her hair works loose and falls over her shoulders; she ignores it and continues to dance. [13]

Would I have seen this element of the play without prompting? I had delighted at the skill of the actor playing Nora in enacting the squirrel or songbird Torvald often talks about her as, yet Justin spoke of squirming over these sections as examples of how romantic love ideologies replicate a kind of fantasy of paedophilia, where the ideal woman is neither angel nor whore but a child, whose behaviour plays at being both of these dangerous potentials. That these are indeed facets of how we live life in some circumstances of conscious or unconscious imprisonment by another and not just part of the repertoire of a very good actor should make us squirm, as Justin suggests. She plays like a child in a way that must seem not only a way of subordinating herself to Torvald but also offering herself as a being vulnerable to his power to rape her: ‘Squirrel would do lots of pretty tricks for you if you granted her wish. … I’d turn myself into a little fairy and dance for you in the moonlight, Torvald’. [14] At other times, with Dr. Rank as Mrs Linde notices, her actions and ambiguous words make her seem, to everyone but her own innocent idea of herself, the seductress that the aptly named Rank wants her to be in his life.

As Mrs Linde observes, Nora is able to do this because she is still acting as a ‘child’. Yet she is savvy enough to know that Rank is the victim of congenital syphilis (a theme explored more fully in Ghosts) for when ‘one has three children, one comes into contact with women who – well, who know about medical matters, and they tell one a thing or two’. [15] No wonder we don’t necessarily see it as simply a sign of Krogstad’s low character when he says to Nora: ‘Oh, you don’t need to play the innocent with me’ [16]. This is one of the many parts of the play, heightened by the fact that it immediately follows Nora’s on-stage promise to her children to ‘start playing again’ once Krogstad goes, where playing games is made as if one meaning with playing countless roles, as no doubt it is for children as G.H. Mead makes clear.

Nora plays the child perfectly, in ways that we react against, and squirm as Justin did (and he is a good measure of appropriate sensitive reactions in a man who wishes to be a feminist in as far as it is possible for a man to be) at an adult being turned into a child in order to buy advantage or assuage power. However, there is always too something hidden in the refusal to be ‘treated as a child’, which is the belief that treating a child in the way thus described is valid and appropriate. But is it? Nora herself in Act 3 believes that her treatment of her children has hitherto been the equivalent of being ‘nothing to them’.[17] Indeed, this must by Act 3 be her active and retrospective judgement of Torvald, whom, at this latter time, ‘can never be anything but a stranger to’ her, except that a ‘miracle of miracles’ occurs [18]. And such ‘miracles’ will not happen without conspicuous shifts of power from those in which it is already established to those in which it is denied. In my view, Ibsen raises the issue of whether those denied power and who require some form of empowerment includes children themselves, in however necessarily mediated a way.

This is a great tribute to this company’s production preparation skills. They unearth the major metaphors of drama at the base of all great productions. One being that actors are not assessed in terms of how each conveys a ‘character’ as if that character was ‘an island’ but as a phenomenon emerging from networks of relationships between the cast’s whole ensemble of shifting roles in relation to each other. This is what I take Jake Murray, the director of Elysium Theatre, to mean, when he cites Michael Meyer’s belief that Ibsen’s drama is not a matter of great actors playing great individual roles but of companies creating relationships between embodied persons in ways that convey the passion of the interactions produced.

A more selfish actress would make the whole play about herself, but not Hannah [Ellis Ryan]. For her it’s very much an ensemble. Michael Meyer, the translator, always used to say that actors who want to grandstand, who aren’t willing to play relationships, always fail with Ibsen, because what fascinated him was the complexity of relationships’. [19]

It does not surprise me then that this company honours authored texts and insists on playing them in ways that open up how relationships are structured not just through encounters between personalities but by relationships also of power, social ideologies and resistance to them, imagination and poetry. The latter elements are necessary because there is nuance even in power relationships and ideological paradigms that pre-structure relationships between men and women, bourgeois and manual working-class persons and between people of different ages, including children as ‘little people’. Three themes in the Elysium Theatre’s rehearsal blog follow up how the cast introjected the necessary theory to play this great drama:

- The metaphor of behaviour as obeying a theatrical or ‘dramatic’ basic structure, including the handling of set and properties (or doors which are both).

- The role of bodies and body proxemics in the elicitation of visceral emotion and embodied passion, as well as action, and,

- the rendering of ideologies and scientific theory (such as the potent nineteenth century theme of the hereditary in character) in terms of the real relationships of which they are the representation.

I have already cited numerous occasions where pleasurable play touches on the notion of pretence and role play which might even be done subconsciously or even unconsciously, for adults as well as children (a theme that might be predictable from the theories of mind in psychology alone). That deceit too is sometimes involved is of course in the mix too – when Krogstad asks Nora not to ‘play the innocent with me’, for instance. The theatre provides a metaphor, as it did also for Erving Goffman, for the analysis of behavioural change or the existence of thoughts, feelings and behaviours in some other ways repressed from sight, even sometimes one’s own, and certainly that of the audience. The company’s blog even makes the point that the effect of the set seen at the play’s opening must ensure ‘that the audience are deceived that the [Helmer] marriage is a good one so that they overlook the darker aspects’, at least in Act 1. Even by day three of rehearsals the themes generally of ‘lies and deception, both to ourselves and others, and the masks we wear in society, not just in public but in private’, were being discussed [20].

Even rooms wear mask and enable distinctions between interior and exterior, public and private by the play with doors being open, shut, or even locked (when Nora pretends that she is rehearsing the tarantella or that she has bought a ‘secret’ costume unbeknownst to Torvald in Act 2, for instance) [21]. Simple acts like Nora pushing her children into the other room, and closing ‘the door behind them’, have weight of meaning on stage – but don’t they too in bourgeois households. [22] According to Meyer, and this is one reason the company chose this translation, good theatrical writing opens the door to language that is inhibited, where persons ‘talk not directly but evasively and in a circumlocutory manner’, ‘saying one thing and meaning another’, enabling an actor’s and a director’s ability to produce nuanced effects of sense and meaning. [23]

Some effects of Ibsen’s exploitation of deep theatrical knowledge (not only as a metaphor) get lost in translation. When reading the play, I came across Torvald rebuking Nora for making her bid to be free of him expressed as: ‘Oh, don’t be melodramatic’. [24] Yet in the theatre I remember having heard ‘don’t be theatrical’, which had started me on the quest for the use of theatrical metaphor in the play. In fact, I had heard correctly. In the rehearsal notes, the director picks up this very choice between two words to convey meaning that would have been more obvious to Ibsen’s audience for they lived in a time when ‘melodrama’ was the hegemonic medium of theatre. Murray says:

It is easy to miss today as melodrama no longer exists as a stage form for us, but in Ibsen’s day it was the dominant genre of the stage. In A Doll’s House Ibsen takes all sorts of elements of it – blackmail, a fatal letter, a husband who promises to stand by his wife and protect her against scandal, a heroic wife willing to sacrifice herself … – only to completely shatter them in the last act. … When Torvald tells Nora to ‘stop being theatrical’ or ‘melodramatic’ … Ibsen is tearing up the sentimental tropes of drama. … Ibsen was working with his audience’s expectations, hooking them into the story, tricking them into thinking they know where it is going only to completely explode it all in the final act’. [25]

No other example shows better how Meyer and Ibsen and thus production strain to help the audience see that the reading of life depends on audiences who read theatre better – for life contains theatre as much as theatre contains life in both are seen as they are – what Ibsen would have thought to be ‘realism’.

The second theme explored by the company was the importance of the visceral body and other body senses than sight alone in the process of theatre. The fate of bodies in relationships is itself a theme. Dr Rank has ‘spinal tuberculosis’ says Nora to Mrs Linde. Yet there are unspoken things in this conversation, such as the attribution of the disease to Rank’s dissolute father. Ibsen would have known as he shows in Ghosts, that hereditary syphilis is a ‘prime sub-soil’ for tuberculosis:

That Nora too possesses such knowledge of body diversities as a result of transgressive passion, though she cannot speak it directly, is fundamental to the play. Even with Rank, she plays games with, rather than name directly, the kind of dissoluteness that characterises Rank’s father as if it were mere pleasures of the appetite more openly to public sight which were concerned (though even eating macaroons can be a secret but guilty pleasure in this play).

RANK: … My poor innocent spine must pay for the fun my father had as a gay young lieutenant.

NORA (at the table left). You mean he was too fond of asparagus and foie gras?

Bodies are visceral things. They are thrown about by their own dynamics in a tarantella (too violently sometimes for the repressed Torvald). They play visibly with the distances they allow between themselves and other bodies, sometimes putting physical barriers (like doors but sometimes items of furniture) between them. Stage directions can direct the acting of much of this. Acted theatre makes much of such proxemics, such as those in which Torvald closes in on Nora sexually (‘Looks at her for a moment, then comes closer’).[26]

However, despite the fact that at least two of the actors mention the fact (such as Michael Blair) that ‘Ibsen’s characters talk a LOT’, Jake Murray makes a key pint as early as day 4 of rehearsals that Ibsen is not in essence a ‘wordy’ dramatist, as we would all agree George Bernard Shaw is.

People often forget that Ibsen’s characters have bodies, by which I mean too often productions focus only on the head, the rational processes of people, the intellectual ideas in the text, rather than viewing the characters as flesh and blood. Ibsen wrote “I am a passionate playwright, and my plays must be done passionately”; in fact, his characters are just like us, driven by their bodily needs, their emotions and passions as they are ideas, in many cases more so. [27]

In our production the words used in the evasive discussion between Nora and Rank raises and evades notions of death, ‘the final filthy process’ of bodily disintegration, appetites sated only by sensual luxury foods and adulterous flirtation of young women with old wealthy dying men were conveyed, as they MUST by the proxemics of bodies touching and standing apart. There are too playful gestures like ‘flicking {Rank] on the ear’ with silk stockings that harmonises with double entendre that raises itself to the cusp of being indecent: ‘I shan’t show you anything else. You’re being naughty’. It is only when Rank becomes too proximate (‘leans over towards her’) that she demands space be created between their bodies (‘Let me pass, please’). [28]

Finally, the rehearsal process (as Murray suggests above) ensures that the ideas in Ibsen’s plays are also realised in networks of bodies in variable spatial relationship. For instance the potent nineteenth century theme of the hereditary in character is important in terms of issues of class and the transmission of physical characteristics, including diseased ones as in Rank’s case) and of imagination and childlike flightiness supposed to be inherited by Nora from her father (at least in Torvald’s mind). But clearly more important for us (given my starting point with a question raised by the possible influence of Medea) is the play’s relationship to its reputation as a classic feminist text (‘a cry for female emancipation’). Jake Murray says of this question, ‘so it is’:

But beyond that it also goes into all the secret, emotional places every man and woman can find themselves in times of crisis – the sense of isolation one feels when suddenly one’s calm, stable, apparently happy existence turns out to be a sham, the shock of learning that someone you loved and thought loved you doesn’t, the fear and uncertainty of facing an insecure future alone and, most of all, the sorrow and pain of ending a marriage or long term relationship even though you know it is essential.

This tries very hard to universalise the tragedy of existence in a new godless universe which Ibsen and his generation ushered in, but it misses the fact that Ibsen knew that such tragedies were usually those of classes who felt entitled to a ‘calm, stable, apparently happy existence’, which in the nineteenth and early twentieth century was the entitled bourgeois classes, ready to claim that those who failed to achieve that did this because they are in some way, like people think Krogstad to be, morally faulty. In fact, the instabilities Nora fears she learns can be survived by her old friend Christine Linde, but also the maid-cum-nanny, Anne-Marie who brought Nora up and is now doing the same for her children. As the actress who plays her (Wynne Potts) in this production says Anne-Marie is:

a woman who’s diligent at her job, trustworthy, kind, compassionate. She is committed to caring for the children +Nora + the family as a whole, partly as it’s in her nature, & also because this family/household has been her source of security all these (25+) years that she’s been in their employment. Their security is her security. I also think she carries a lot of subconscious pain about having had to give up her child, but that it’s stuffed right down: she’s not conscious of it most of the time. But it surfaces when she has that conversation with Nora on pg 55 (actually 56) – especially when she refers to having heard from her daughter twice (only twice in her life!) once being when she got married.

The point is that Anne-Marie has faced every tragedy that Nora will face and has not buckled because she has no perceived entitlement to safety and security being working class (as Mrs Linde nearly becomes) on her husband’s death. The majority of women have never been caged mammals or ‘songbirds’ (as Nora becomes to Helmer) but have not even had the security that is like imprisonment to complain about, and, of course, Anne-Marie does not complain. I’ll finish with her speech to Nora, from which Nora silently learns. However, the surprise seems to be that this is the first time Nora has ever shown interest in Anne-Marie’s past (when, that is, it touches on her own future).

NURSE: Well, children get used to anything in time.

NORA: Do you think so? Do you think they would forget their mother if she went away from them – for ever? … Tell me, Anne-Marie – I’ve often wondered. How could you give your children away – to strangers?

NURSE: But I had to when I came to nurse my little miss Nora.

NORA: Do you mean you wanted to?

NURSE: When I had the chance of a good job? A poor girl what’s got into trouble can’t afford to pick and choose. …

This feels to me the brilliance of insight that allowed Ibsen to become, in England, the vanguard of an intersectional socialism, where class and gender (at the least) were necessary to account for understanding intelligently (even emotionally intelligently) the nature of oppression.

And yes, in the end Justin is right. Medea does not deal with understanding the oppression of women in this way but only in one suitable to a more brutal time and place, where visceral bodily reality and violence is openly referred to. Well, it helps to talk. That’s my excuse. LOL.

All my love

Steve

[1] Jake Murray and others (2022: Playing Torvald 6/9/2022) in ‘A Doll’s House – various blogs’, Elysium Theatre Company Blog. Available at: https://elysiumtc.co.uk/2022/06/14/elysium-theatre-company-2022-update/

[2] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990: Act 1, p.23] The Doll’s House in Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) Plays : Two (A Doll’s House, An Enemy of the People, Hedda Gabler) published in London by Methuen Drama, 23 – 104

[3] Ibid: Act 1, p.50

[4] Playing Torvald 6/9/2022) in Jake Murray and others (2022 op.cit).

[5] Ibid: Act 1, p.43

[6] Ibid: Act 1, p. 50

[7] Brons, Lajos (2015) ‘Othering, An Analysis’ in Transcience, a Journal of Global Studies (2015/01/01, vol. 6) 69 – 90.

[8] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990 op.cit.]: Act 3, p. 98

[9] ibid: Act 2, p. 77

[10] Ibid: Act 2, pp.76f.

[11] Ibid: Act 1, p.51.

[12] Ibid: Act 2, p.57

[13] Ibid: Act 2, p.77

[14] Ibid: Act 2, p.60f.

[15] Ibid: Act 2, p.58

[16] Ibid: Act 1, p.45.

[17] ibid Act 3, p. 103.

[18] Ibid: Act 3, p. 104

[19] Jake Murray and others (2022: Playing Torvald 6/9/2022) in ‘A Doll’s House – various blogs’, Elysium Theatre Company Blog. Available at: https://elysiumtc.co.uk/2022/06/14/elysium-theatre-company-2022-update/

[20] Jake Murray and others (2022: Playing Krogstad 12/9/2022 & Playing Christine 7/9.2022 respectively) in ibid.

[21] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990 op.cit.]: Act 2, pp. 73 – 75 involves complex double-play with the meaning of doors as access to secrets and deceit, even simple and ‘innocent’ ones, like trying on a dress.

[22] ibid: Act 1, p. 50

[23] Jake Murray and others (2022: A Tribute to Michael Meyer 27/8/2022) in Jake Murray et al. op.cit.

[24] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990 op.cit.]: Act 3, pp. 94

[25] Jake Murray and others (2022: Rehearsal Process: Summing Up 25/9/2022) in Jake Murray et al. op.cit.

[26] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990 op.cit.]: Act 3, p. 87

[27] Jake Murray and others (2022: Playing Dr. Rank 8/9/2022) in Jake Murray et al. op.cit.

[28] Henrik Ibsen (trans Michael Meyer) [1990 op.cit.]: Act 2, pp. 64 – 68.

5 thoughts on “‘The biggest task of the show is the actress playing Nora’s (sic.). … A more selfish actress would make the whole play about herself, but not Hannah [Ellis Ryan]. For her it’s very much an ensemble. Michael Meyer, the translator, always used to say that actors who want to grandstand, who aren’t willing to play relationships, always fail with Ibsen, because what fascinated him was the complexity of relationships’. This blog discusses the production of Henrik Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’ (Michael Meyer translation) by Elysium Theatre Company played on 14th October at Bishop Auckland Town Hall. References to text (not in all precise respects like the production adapted one) from Henrik Ibsen (translated Michael Meyer) [1990: 23 – 104] ‘Plays: Two’.”