‘The time has come to be reflective’.[1] Do artists who have lived a very long and full life prefer to experience ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’ (to which Wordsworth traced the origin of poems) now it can no longer be keenly experienced in action? It would be easy to attribute an actor and novelist’s turn to poetry (as in the case of the octogenarian Paul Bailey) as illustrating precisely that turn. But these poems queer our conception of the development we call normative aging, developing that space in an old queer man’s body wherein we still feel ‘inclined to the wild unreason / that’s unbecoming in a man my age / and seeming dignity’.[2] This blog, with personal reflections of my own, discusses the significance of the poems of Paul Bailey in the volumes entitled Inheritance (2019) & Joie de Vivre (2022) both published in London by CB Editions.

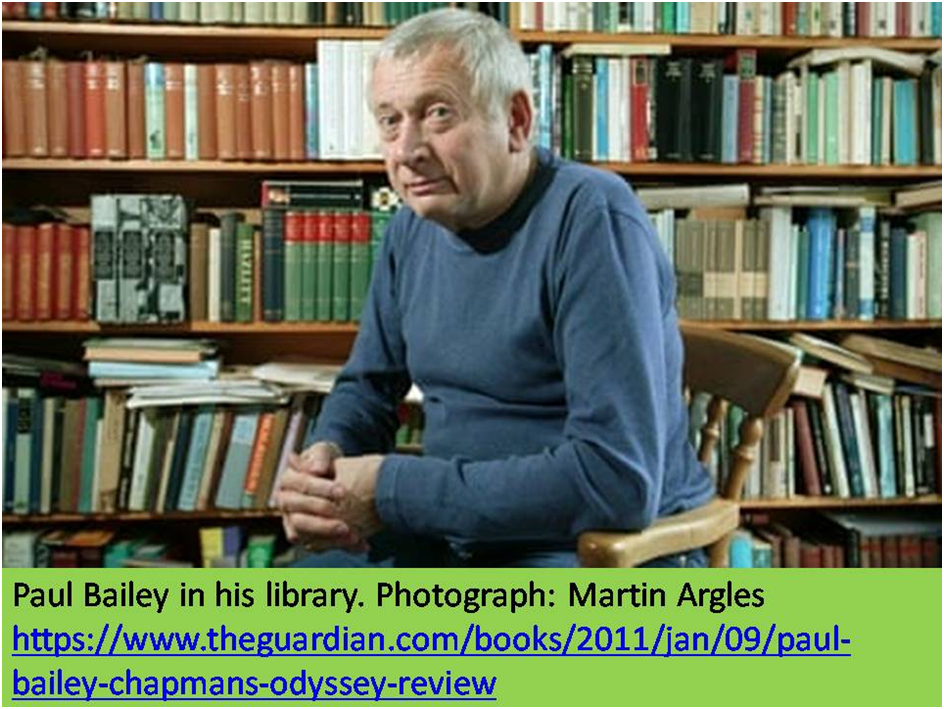

In my youth, Paul Bailey was a major literary figure and represented a metropolitan culture that was at odds to the mainstream of London literary culture and its Oxbridge educated (in the main) elites. For instance, he is capable of dismissing with contempt The Booker Prize, of which he was clearly contemptuous in this journalistic salvo In The Guardian of 2012, about the presumptuous nature of literature’s glittering prizes in the UK, which measure up ill to the USA’s Pulitzer Prize:

The Pulitzer, which honoured the ageing William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway for the grandiose and simplistic follies of their maturity, has assumed the character of a national institution. Its word goes. That word, it is a relief to record, has somehow eluded the Man Booker prize, and one must pray that it continues to do so. I remember the anguish I experienced as I turned the leaden pages of The Bone People by Keri Hulme, which won in 1985, or endured the repellent sentimentality of Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, the 2002 winner, to name but two of the stinkers the Booker judges have deemed fit to celebrate. If that’s the word, you can stuff it.[3]

It would be easy to scoff back at such generalising judgements based on the subjective measure of Bailey’s sense of being a bold voice from the working classes fighting back the pretensions of a mainstream bourgeois intelligentsia. Moreover, as Robert McCrum once said at some length Bailey’s ability to live as an artist from writing was in large part based on the renaissance of literary fiction caused by the Booker Prize’s support of ‘literary’ fiction.

In retrospect, the turning point in British writers’ fortunes came in 1980. The Booker was televised, and the next year Salman Rushdie won with Midnight’s Children. After that, it was what the literary agent Peter Straus calls “a halcyon summer for literary fiction”. Embodied in the sardonic, transgressive figure of Martin Amis, fiction was suddenly fashionable. [4]

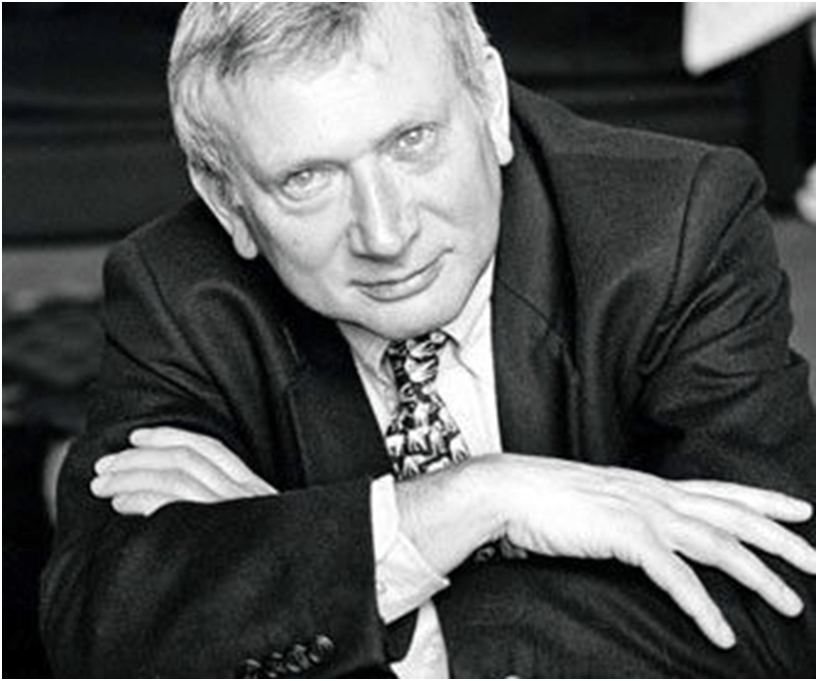

However, Bailey’s literary hero of all time was Dickens. Leo Robson in a review of a later novel by Bailey scans Bailey’s career as a novelist in these terms as one of those rare writers: ‘who strives to emulate Dickens’s mixture of comedy and pathos rather than simply being, in one broad feature or another, “Dickensian”’.[5] The identification went deeper, of course. Even in Chapman’s Odyssey, the novel reviewed by Robson, the title character is visited by “Philip Pirrip, he of the great expectations”.[6] The main character of Dickens’ Great Expectations is clearly a much refined version of Dickens experience of coming into wealth and social status after a horrifying experience of abandonment, for so it feels, he had explored in David Copperfield, and in a sense they are both deeply autobiographic. And Bailey himself clearly identified with Dickens and his literary-fictional avatar, Philip Pirrip (or Pip as he names himself in the novel), for he said so in a retrospective look at the novel in The Guardian in 2008.

… it’s the earlier, ungrateful Pip I recognise. I recognise him with shame, as Pip himself comes to do. I can still blush whenever I encounter the younger Pip, whose coldness, although temporary, is of the kind that always accompanies the overestimation of one’s own value. There was a time in my life when, like Pip, I was ashamed of my working-class origins, and embarrassed by my unlettered relatives. My then embarrassment has continued to embarrass me for decades: how restricted it was, both by class and convention, and how readily it responded to a dropped aitch or a harmless social gaffe.[7]

I have prefaced my remarks at such length to show implicitly that Bailey has always been someone who reflected on his life and did so by virtue of the reading which he felt lifted him from his ‘unlettered’ origins. Yet it still allows him those ‘spots of commonness’ to lift and take the poison out of George Eliot’s phrase about by the self-consciousness of the middle-class arriviste from the lower classes that can allow him to use phrases like ‘stuff it’ to condemn the ‘stinkers’ which pass for great novels by Booker Prize judges of the past. He combines such direct language of the street with elegant phraseology to show he can do refinement whilst achieving enough distance from it to brand it the language of a class capable of pretension. And linked to that is the clever mixture of ‘comedy and pathos’, as identified in his novels by Robson the quotation above, which comes from that deep identification with Dickens as an artist as well as indirect biographer. And that is true of the poetry too, which keeps intruding upon the commonplace of a poet’s reflections on his older age material that is rarely poeticized because socially embarrassing, earthy, common or which queers the norms of poetry, especially romantic poetry.

Carol Rumens is one of the few to mention his poems in the press, but she is an award-winning poet herself.[8] She chose a poem from Joie de Vivre, entitled Nocturnal, as her Poem of the Week in the Guardian for Monday 11 April 2022 in the week of the publication of Bailey’s second volume of ‘late’ poems. She too emphasises ‘comedy and pathos’ linking it to the exploration of queer experience, which she would perhaps prefer to call ‘gay’ experience:

“Now I am gloomily gay, or gaily gloomy, / and philosophical,” his speaker concludes in Raised by Hand. There are smiles, painful and otherwise, hearty laughs and remembered plaisir d’amour in the assorted poems, translations and deliciously subversive prose anecdotes of Joie de Vivre. While being “gloomily gay” suggests a possibly dolorous note to the gayness (in both old and modern senses of the word) dolour couldn’t be farther from the Bailey style. Nonetheless, the gently sunlit landscape has its shadows.

What Rumens does not consider here is that the line she plays upon here comes from a poem whose very title takes us back to Bailey’s identification with Pip in Great Expectations, since Raised by Hand is a phrase used by Pip’s sister to describe her care of Pip when he is orphaned. Some people speculate about the meaning of the phrase but, despite the reasonableness of that speculation (relevantly too in relation to the fear of punishment), the association with class (given the play on the word ‘hand’ to indicate the manual labourer in Hard Times, is unmistakable in the context of Dickens’ treatment of Pip. In the poem the phrase ‘raised by hand’ has a more direct application to adolescent masturbation (the poem locates the acts referred to by Paul as happening at the age of 12 or 13 – ‘Seventy years have passed’) and its outcomes.

There was always gloominess afterwards

when guilt informed my stiffening handkerchief

that I’d been bad, and worse than bad,

to let my less-than-natural feelings

take such possession of me.[9]

One of the joys of this poem, to a queer reader like myself, is the play with the grammatical and lexical status of the word ‘gay’, particularly as a category noun tied to identification of persons, in much richer ways than Rumens indicates who merely points to the ‘modern’ and older meanings of the term (a simplification anyway of the twists and turns of interactions between its usage in particular situated contexts and its etymology). It is possible, though colloquial (equivalent to Little Britain’s ‘only gay in the village’), to say ‘I am a gay’ rather than ‘I am gay’ (where the word in the latter is descriptive rather than nominal) it is almost unknown to indicate one is ‘a gloom’, as in: ‘I was a gloom before I was a gay’. I have never heard the word gloom as a noun personally but it sets the right context for understanding how and why the term ‘gay’, though strategically useful for a portion of our history and activism, is not a useful identifier in the long duration of our history of a category of identity. And hence my preference for the term ‘queer’.

In his first volume of poems, Inheritance, Bailey had attributed and complicated his personal gaiety, frivolous nature (in a poem named ‘Gaiety’) to being ‘sustained by sorrow’, combining his comedy with pathos from the very beginning of his life and particularly from his near-death as a child: being a ‘funny little so-and-so’ according to his acerbic mother, the nearest we get to the double-edge in the adjective ‘queer’ being this double-edge on ‘funny’, suggesting at the same time both mirth and alienating strangeness.[10] The first line of Raised by Hand making the same connections between moods but tying those associated opposites now not to near-death experience but to his sexual experience by hand and handkerchief and the link, via, guilt, to the fragments of his personality: ‘gloomily gay, or gaily gloomy, / and philosophical’. It is not enough to gloss this in relation to the rest of the poems in Joie de Vivre merely to a succession of ‘smiles, painful and otherwise, hearty laughs and remembered plaisir d’amour’ for it is the queer intermixture of interacting modes of being and moods in feeling that the poem get at not linear successions of the same – the way negatives ‘informed’ the positives and vice-versa.

I think Bailey uses the term ‘informed’ in this rich way in this poem, guilt plays the part of the seminal fluid (and vice versa) which stiffens his handkerchief into a more hardened form from within. It’s a severe form of reflection on the genesis of one’s personae which invites all kinds of ambiguity, including those of class and status. The latter perhaps emerge in the ‘crazily wonder-struck’ phenomenon of a working-class boy (that fact being revealed by the naming of his ‘small back bedroom / overlooking the railway’) giving himself (and surely we cannot imagine the gift being accepted other than in fantasy) to the physical prowess and social status of the great film-star, Marlon Brando.

The poems seem to indicate that Joie de Vivre is more than a phrase but a statement that gets shaped, ‘informed’ as it were, by the sorrow and the philosophical that unite in Bailey’s reflections. Rumens discover this mix in ‘the narrative tone’ of the poem Nocturnal itself, which ‘evokes the unnamed protagonist, the man “who really did prefer oblivion” yet “saw the funny side of almost everything”.[11] This man is identified as a lost but unnamed lover of Bailey’s but he is also another avatar of the poet himself, taking his common identity as everyman from the ‘rejection of the laborious virtue of positive thinking’ that Rumens argues was the way W.H. Auden too ‘interpreted the ancient Greek perspective on existence: “Not to be born is the best for man”’ (the link is given by Rumens).[12] The subject, of course of the poem is precisely ‘a man who wished he hadn’t been born’. This is all very darkly mournful, as suits a setting at night of course, but it is also accepting not only of sorrow but of multiple queer love-matches, even those tinged with sadness, (and the fact that they are multiple is implied, and not necessarily with the same man, by ‘those’ in what follows) completed:

on one of those perfect mornings

that always follow

a night of rapture.[13]

The queer acceptance is also part of the pathos in the tone of comic self-mocking implied by the warm appreciation of ‘understatement’, to use the word in the poem itself. This tone is not confined to those who die using ‘understatement’ since the ‘quizzically humorous voice’ also plays through the quite dramatic suicide (and the narrator’s ambivalent response to it) of the lover Paolo recorded in the poem preceding Nocturnal named Paolo’s Leap.[14] The memory of old loves in which memory, guilt and desire mix in very queer ways is not new to poetry. It is the staple of Thomas Hardy’s beautiful and finest work and which shows at its best, appropriately, in the poem commemorating the ‘delicate gold necklace’ bought for him by his long-time partner named The Bestowal.[15] However, to stir into this mixture a kind of fun that sometimes turns pathos into bathos is special to Bailey and related to the complex way in which the poet performs gaiety (as emotional ambivalence sometimes linked to the social oppression of being born gay in 1937.

Let’s take the title poem of the collection: Joie de Vivre.[16] The phrase has an interesting history that touches even on the influential existential psychologists like Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. The latter defined ‘self-actualization’ (perhaps the greatest good for an existentialist in term of it: ‘”the quiet joy in being one’s self…a spontaneous relaxed enjoyment, a primitive joie de vivre“’.[17] Yet self is not so easy to actualize for Bailey as he ages without taking into account the machinery and apparatus that sustain the processes of his living such as a pacemaker (‘a battery that keeps me ticking’) and daily medication (‘at least twenty pills a day’). Indeed the play on the common idiom ‘keep me ticking’ referring to the everyday phrase for being sustained in life also makes him into a wristwatch registering time, just as does the metre of a verse line literally measure time and pace in a poem: ‘measured sorrow and delight’. And we should not forget that Bailey is, despite the everyday idioms, an allusive poet. This is his ‘April’ poem and like other classic formulations April is a time for feeling life surge, just as Chaucer does in the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales.

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye,

So priketh hem Natúre in hir corages,

…[18]

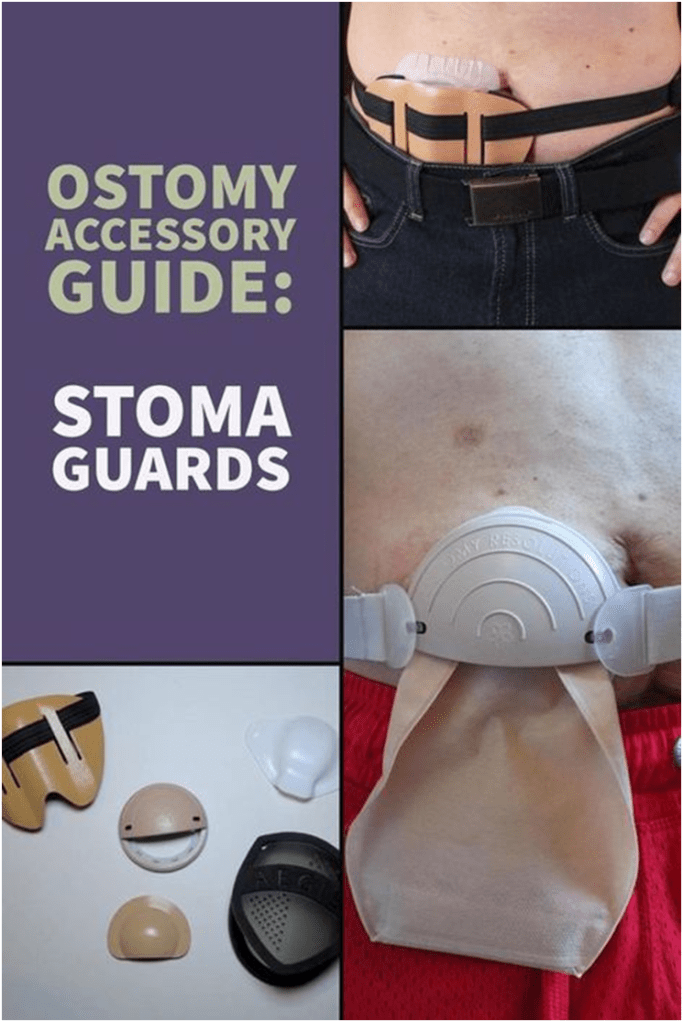

Joie de vivre is therefore an English as well as a French (or psychodynamic) trope. A perfect one to bind self-actualization to the part played in it by bodily sensation of the flow of ‘licóur’, sweet breath and youthful energy. But despite seeing the ‘hyacinths and tulips in the garden’, what Bailey’s aging narrator feels on April Fools’ Day 2020 is that his ‘body’s not what it was’ and the only ‘licóur’ flowing is between itself and an external object substituting for his life functions whose sound might be measured (as poetry is measured by metre), one named after the hole that pierces the body to allow the exit of excremental waste (actually a stoma bag since the stoma is only the name of the hole in the body that necessitates the bag). In fact, this abbreviation in everyday language whereby a part represents the whole called metonymy is one of the linguistic tricks that the poet utilises and exploits here – confusing the cusp of body (the stoma) and the artificial body accessory (the stoma bag).

I listen to the waste making its way

into the stoma that I’ve had to wear

for ten confusing months

and almost marvel at the sound it’s making.

The stoma bag being worn at a body stoma.

Such music is a ‘marvel’ (perhaps as much as the symptoms of youthful spring heard in Chaucer’s verse). This is somewhat a deeper point than it might appear, because the transformation of joie de vivre into the stuff of ‘waste’ was, as Bailey knew – which I will go to show). We might like to think that this poetry is the reflective fruit of an artist singing in his latter-day poetry, forever, Last Poems like Yeats as well as Later Lyrics by Hardy.

That is because old age and the potential to the music of wasted lives in older age has been Bailey’s subject even since he was a young man and artist. His first novel (in 1967 when Bailey was 30), At The Jerusalem, is described on the publisher’s first edition dust jacket flyleaf as a ‘compassionate and minute observation of loneliness and displacement among the old’. And it’s theme of loneliness and displacement is expressed by the sense of a life gone to waste. The terms which define ‘waste’ in relation to a life without joy are very much those used to scare men from being or living as queer, here are the character, Thelma’s late reflections of life at ‘The Jerusalem’, an older person’s home made from a converted workhouse:

She’d faced pettiness every single day. She’d tried to accustom herself to a loveless existence. … That house had brought her down. She’d gone into it with some opinion of herself. She left it a thing, waste to be disposed of; … (my italics)[19]

I am not saying that the subject of this novel is a mere allegory of the oppression faced by queer men and women but that there was a reason why a relatively young queer man, torn between joy and despair in life, turned to older person’s as a constant subject matter for all of his novels in some large or smaller part, for indeed he did this. Partly, it is the sense that the accusation (or even self-perception) of living a wasted life was often the lot of him and other men, even up to my youth in the 1960s. I remember well (for it is the first of his novels I read whilst a student) his novel Old Soldiers appearing to some acclaim in 1980, which traced in part the feeling of a loveless life of a widower after the death of his wife. It was applauded though because of the word-picture of an older queer (bisexual) male poet, called characteristically Julian: ‘the misfit in corduroy’, whom the gentrifying new neighbours in Islington (I remember the process of transformation well) ‘warned their attractive children not to speak’.[20] Interesting the elder poet is informative about the one Bailey himself was to come over forty years later> he is responding not only to his own feeling about a belated wasted life in old age but to the older age of poetry itself, where common images of joy are displace by ‘The Waste Land’ by T.S. Eliot (of whom Julian says: “Not for nothing … is his name an anagram of ‘toilets’”).[21] It appears that excremental waste was tied to the modern condition too and to poetry in ways that might directly precede (cognitively at the least) the music of waste passing through a stoma. This is because our poetry is belated and the poet no longer ‘a connoisseur of language – his every word is a note in music’. Julian goes on to say from his pedestal at Hyde Park Corner:

Today’s poets, if one could call them such, had forsaken the Parnassian slopes – where sweet rivulets sparkle yet midst verdant pastures – for the coarse clay of the modern world. The Grecian urn had been replaced by the teapot and the beer bottle, neither of which vessels had the fearful symmetry to inspire a true disciple of Apollo to thoughts of immortality. Muck, filth, slime: these were the properties of contemporary verse. …, the sense of Wonder, of the wide world being Wondrous and Wonderful, that sense was missing.[22]

And thus the fate of ‘the joy of living’ in modern art: turned to ‘waste’ material on which to reflect: no longer the spring celebrated by Chaucer’s vibrantly sexualised crew (even the Pardoner who is clearly aligned with queer sexuality and false religion (each being a metaphor for the other he claims in Chaucer and some contemporaries) in Richard Firth Green’s essay on the Harvard University Chaucer website) has become T. S. Eliot’s (‘toilets’) The Waste Land (the title not being irrelevant – life has become excremental waste not unlike in Alexander Pope’s The Dunciad, in another literary age of excremental vision):

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.[23]

For me this long excursion deepens the reason why Bailey’s title poem is an April poem – one wherein the ‘note of music’ is the flow of ‘waste’ too. Hence the mix of pathos and comedy turning to bathos, for Bailey said he expected to die at the age of 30 (when he in fact published his first novel):

But, what the fuck, I’m here –

sustained by medicine and metal –

and writing the poetry

I knew I’d write, but didn’t,

Before I evaporated

At the age of thirty,

…[24]

Many of the poems explore the origin of feeling himself to have a life wasted from the start, such as his mother’s lack of overt attachment, fear of ‘destitution’ and his own early bad health and near-death.[25] The Staff of Life is a prose-poem detailing seeing a ‘drunk’ pick up and eat food otherwise wasted: ‘a rain-soaked bread roll’.[26] The prose-poem To Sadie is based on a specialist form of waste (‘poudrette … a manure made of night-soil mixed with charcoal’) turned to something useful and celebrates literary agency.[27] The latter contains my whole argument about the volume. Some of the poems both regret and celebrate ‘wasted’ opportunities to make love to a man he adored because instead he: ‘… sent him a prudish scowl. / I wish I hadn’t. For years and years and years / I wished I hadn’t’.[28] Equally there are poems of joy at having followed the prompt to joie de vivre, such as ‘the death-defying adventure’ with Giacomo in a Venice winter, or a ferryman in Istanbul.[29]

There is a brilliant allegory in another poem of how the feeling of being belated becomes a sustaining reflection that blesses the memories of the past and the uncertain past, which I cite in my title. What matters about this beautiful poem is that it uses the course of a gathering for evening drinks to show that nothing has been or need to be wasted in its coarse passage, just as in life, for recurrence of the past is a present given and makes an uncertain future sustainable.

The time has come to be reflective,

to talk of the past, such as it is,

and the future, perhaps,

of which we’re uncertain.[30]

At its funniest and most bathetic it is represented in the ‘unbecoming’ resurrection that is the return of penile erection to an old queer man’s body who had missed this joy in living during his cancer treatment:

But then, once the treatment was over,

The old Adam returned

Slowly, determinedly,

With his promises of bliss

And I feel imprisoned once more

inclined to the wild unreason

that’s unbecoming in a man my age

and seeming dignity’.[31]

In much the same way he celebrates not only the divine poems of clerical Metaphysical poet, Thomas Traherne, discovered because his poems were confused with Henry Vaughan, whose most well remembered poem wherein ‘he saw eternity the other night’ but which is here cited as if by Traherne, but for his final evacuation of the earth – his last ‘dump’ in the toilet wherein he ‘suddenly found himself / like other mortals’.[32] In other words, you can’t keep the ingrained earthy democracy of a working-class lad turned to reflection by queerness (even in the experience of death) down from mouthing his determination to ‘cut through the crap’, like that mouthed by supposedly straight men when they try out gay sex in is great poem in Inheritance, named Ancestral Voices.

… it was funny, they said, the

Things you did when the drink got the better

of you. …

Ancestral Voices lines 19ff. in Inheritance p. 28f.

Let’s honour him a truth-teller for that’s what queerness is, and it is all the better when it stands out bourgeois conventions it otherwise has to honour too. Innit!

All my love

Steve

[1] Paul Bailey (2022) from Gathering line 11, p.50 in Paul Bailey Joie de Vivre London, CB Editions.

[2] Corporeal line 14ff, p. 62 in ibid.

[3] Paul Bailey (2012) ‘I Prefer humble prizes’ in The Guardian (online) [Fri 13 Jul 2012 22.55 BST]

[4] Robert McCrum(2010) ‘Last year was sheer hell for the novelist Paul Bailey. Better times may be here’ In The Observer (online) Sun 7 Mar 2010 00.05 GMT. Available at:https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/mar/07/google-writers-ebooks-publishing

[5]Leo Robson (2011) ‘Review of Chapman’s Odyssey’ in The Guardian (online) [Sun 9 Jan 2011 00.05 GMT]

[6] Cited ibid.

[7] Paul Bailey (2008) ‘Black ingratitude’ – an article on Dickens’ Great Expectations, in The Guardian (online) available In: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/mar/08/featuresreviews.guardianreview32

[8] Carol Rumens (2022) ‘Poem of the week: Nocturnal by Paul Bailey’ in The Guardian Online (Mon 11 Apr 2022 10.00 BST Last modified on Mon 11 Apr 2022 10.02 BST)

[9] Raised by hand line 14ff, p. 24 in Paul Bailey 2022 op.cit.

[10] Paul Bailey (2019) from Gaiety, p.5 in Paul Bailey Inheritance, London, CB Editions.

[11] Carol Rumens op.cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Nocturnal line 9ff, p. 45 in Paul Bailey 2022 op.cit.

[14] Paolo’s Leap line 17, p. 44 in ibid.

[15] Bestowal line 3, p. 27 in ibid.

[16] Joie de Vivre p.3 in ibid.

[17] Rogers, Carl R (1961). On becoming a person: a therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, MA, USA: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 87–88 Cited in Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joie_de_vivre

[18] Find at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43926/the-canterbury-tales-general-prologue

[19] Paul Bailey (1967: 165) At The Jerusalem London, Jonathan Cape.

[20] Paul Bailey (1980: 56f.) Old Soldiers London, Jonathan Cape

[21] Ibid: 64

[22] Ibid: 63f.

[23] For text see: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47311/the-waste-land

[24] Rejuvenation line 10ff, p. 9 in Paul Bailey 2022 op.cit.

[25] See Provision line 8, p. 19 in ibid.

[26] The Staff of Life line 1, p.21 in ibid.

[27] To Sadie line 2-4, p.55ff. in ibid.

[28] Tar Brush line 15ff. p. 25 in ibid.

[29] In Winter & Transport, pp. 32f. & 34f. in ibid.

[30] Gathering line 11ff. P. 50 in ibid.

[31] Corporeal line 10ff, p. 62 in ibid.

[32] Heavenwards p. 74 in ibid. I do not know why the Vaughan is evoked here as if by Traherne.