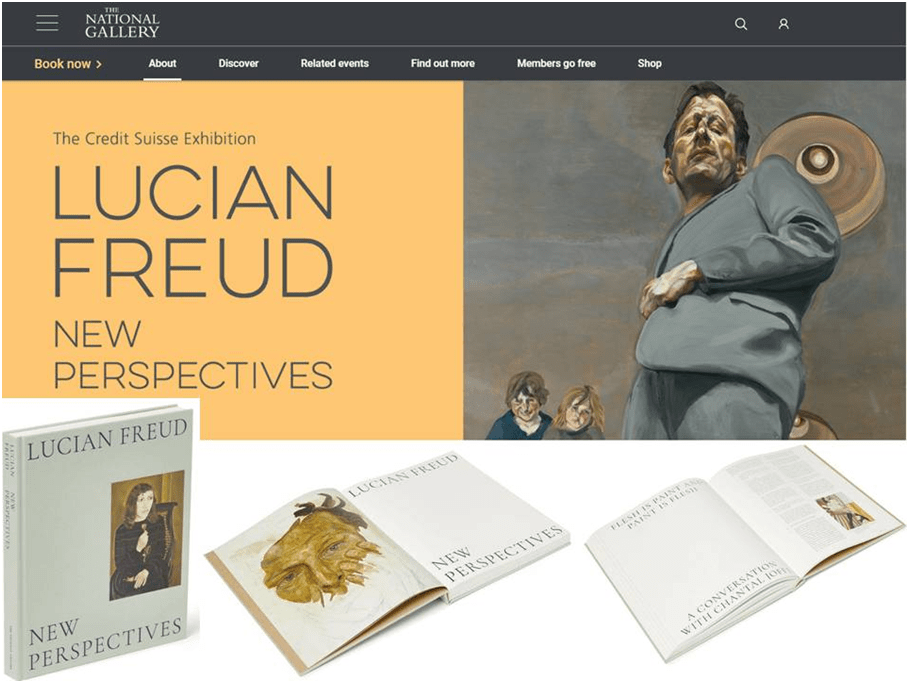

The Credit Suisse Exhibition, Lucian Freud: New Perspectives is, according to Laura Cumming in The Observer the artist ‘stripped bare: …. No emphasis on the biography, behaviour or love life; no abasement before genius, just the revelation of the paintings as works of art to celebrate the centenary of Freud’s birth. … Freud’s portraits can speak for themselves. The curator, Daniel Herrmann, even includes paintings so mediocre they are actively instructive; allowing the eye to perceive what defines the great works’.[1] This blog starts with musing upon the nature of mainstream media art reviews but is intended mainly to contain my thoughts prior to visiting the exhibition in London on 30th November 2022. It is done after reading the catalogue by Daniel F. Hermann (Ed.) named Lucian Freud: New Perspectives & published in London by National Gallery Global in association with Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

I sometimes muse about the value of art criticism for anyone other than for the person who generates it as part of their own learning plan. This is even truer in its latent forms in art history, in which assumptions and presumptions sometimes take the place of judgements about the significance of artists or movements in and between historical periods. I think I started thinking about this as a result of reading in close proximity two contrasting reviews of the recently opened Credit Suisse exhibition of Lucian Freud at the National Gallery. It is an odious thing to confine oneself to such comparisons for there could not be greater distance between the review by Laura Cumming in The Observer, cited in my title (and I will return to the generosity and qualities of that review later in this blog) and that in The Sunday Times by Waldemar Januszczak.

So great is that distance, there is almost an invitation to binary comparisons between these two reviews which might unfairly evoke other absolutist binaries like good and bad, other-centred and self-centred, and perhaps, even, female and male. The invitation must be rejected, by me at least, because I think there is as little value in such binary absolutes in this context as there is any other. A corrective for any remnant of such thinking can be found in my use later of Jonathan Jones’ review in The Guardian, who is not usually an art critic I much like. His review is quite different from the two I have just mentioned and raises no substantive issues relevant to my concerns in this blog. However, because, in this case I admire the piece and see it as a useful and appropriately generous attempt to value the critical work of other eyes than his own, it is appropriate that it set some norms of good-enough practice, at a degree of intensity much lower than Laura Cumming.

Waldemar Januszczak’s review in The Sunday Times frames discussion of the exhibition around one rather acid rhetorical question and statements about the otiose ‘huff and puff’ of curatorship in the case of this exhibition [2]. Januszczak writes:

…, what is [this exhibition] doing at the National Gallery, occupying the same old master rooms occupied most recently by Raphael and before that by Titian? Freud (1922 – 2011) was a sizzling contemporary presence, no arguments there, but does he deserve such a grand promotion to the ranks of Raphael and Titian?’[3]

Second, he critiques the ‘arrangement of the show itself’, finding it without chronological or other significant coherence. Finally, he questions the value of curation (and perhaps particularly the curation here): ‘Forget the curators. Follow the artist’. This attitude segues into a dislike for the assumption that curators do, or even can, provide ‘new perspectives’ (part of the title of this show – and perhaps others) which avoids the too overtly biographical and the weight of past genius in art. It is the biographical context which must be asserted, the critic continues, since, according to him, the most intense of Freud’s work is that in the self-portraits and that: ‘This fierce appetite for self-portraiture needs surely to be understood in biographical and psychological terms – sorry, curators’.[4]

Nothing can be clearer here than that the critic feels he has been failed and that this feeling equates with letting down any other art-lover with an eye for the painting of past masters and a veneration that equals the baroque grandiosity of the architecturally huge rooms showcasing the exhibition. Such an eye, Januszczak seems to suggest, will not confuse the ‘huff and puff’ that the current National Gallery curator feels is needed to make a ‘sizzling’ modern painter look as globally and historically significant as are Raphael and Titian. He goes to add that curation like that in this show also manages ‘to be awkward’ in at least two ways.

First, they select paintings that are not meaningful in the way the rationale of theor own curation wants them to be such as the portrait of Andrew Parker Bowles (whom Januszczak names as only – riffing on Freud’s non-biographical title for the painting – ‘a middle-aged brigadier in his unbuttoned uniform’). Laura Cumming also finds room to disagree with the curatorial interpretation of this painting as an exemplum primarily of paradoxically clothed fleshiness but in MUCH more interesting ways. Second, they fail to select paintings (‘five or six’ Januszczak says) ‘that would have made it a more complete story’.

At this point I wondered which ‘story’ the curators are being said to miss for many stories are told about the context of the paintings except perhaps that consonant with the chronology of Freud’s life and influences but mostly of wives, female sexual partners and children. Most of us feel this story has been told many times and is anyway sufficiently covered by an appendix to the catalogue entitled ‘Chronology’. I will look later at rather different genres of ‘story’ which this show liberates to enhance (in my view totally correctly) the significance of this artist. However, before moving away from Januszczak, I wonder whether his view of the curators of this show is coloured by the tawdry appearance of his earlier views of Lucian Freud as recorded in Gregory Salter’s catalogue essay? It must have been galling to be reminded by Salter of his presumption that Freud’s interest in abundantly fleshy women and queer men was merely in the interests of capturing the ‘freakish’ in the manner, Januszczak argues, of Velasquez’s paintings of court ‘dwarfs’.

We wince at the unnecessary social insensitivity and arrogance of the exclusive language here but it was not unusual in 1988 to write of people who differed from the norm using the term ‘freak’ quite uncritically.[5] Even Freud’s interest in the flesh of Sue Tilley was, Salter goes on to say, characterised as part of Freud’s interest in ‘low’ subjects of public scorn, although his tone is pitying: Tilley was, Januszczak said in 1994, ‘a shapeless emblem of an age of unkindness’ and shows Freud ‘at his most Sunday Sportish’. [6] Needles to say pity for people thought of as ‘freaks’ is not a great advance on scorn for it is our perception and naming of that perception that is at fault. I do not think Freud is operating at the level of The Sunday Sport at all here. [7] Neither, to my surprise, does Jonathan Jones in The Guardian who speaks of Freud’s Tilley figure thus: ’Sue Tilley, whose magnificent, mottled flesh fills your brain as you contemplate her in one of the last grand canvases here, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet’. [8] I agree but would have chosen a better adjective than ‘mottled’.

In choosing a better word could it have been surpassed by Chantal Joffe, interviewed in the catalogue by the editor? She says:

Freud is extraordinary on sleepers and people’s interiority. I don’t get harshness, I get the beauty of the human body. The flesh itself is very beautiful, and it’s paint. Flesh is paint and paint is flesh.[9]

Surely, despite Januszczak’s insistence otherwise, the ‘new perspectives’ in this show are precisely those of new and fresh voices that see beauty and sensitivity, as Joffe does as a practising artist herself, where others see freakishness or worse in the human flesh. So even if it is true, and I think it is, that none of the insistence that Freud ‘treated paint like flesh and flesh like paint … adds up to a new perspective’, the freeing of the eye of the gallery visitor from curator hints does facilitate the emergence of ‘new perspectives’, even if only of those of each gallery viewer. In fact, Laura Cumming shows us that Hermann does the opposite of what he is accused of by Januszczak. Thus says Cumming:

Lucian Freud stripped bare: …. No emphasis on the biography, behaviour or love life; no abasement before genius, just the revelation of the paintings as works of art to celebrate the centenary of Freud’s birth.

This is tonic; a liberation from the grand master hush. It is also surprisingly unusual. Without the usual wall texts, occasionally no more than elevated gossip and without the exalted claims for his vision of humanity, Freud’s portraits can speak for themselves. The curator, Daniel Herrmann, even includes paintings so mediocre they are actively instructive, allowing the eye to perceive what defines the great works.[10]

Art criticism like this astounds because it represents accurately the necessity of curatorship and the contest of values within that practice. While others quibble at someone else’s selection from a vast oeuvre where resources are necessarily far from ideal, Cumming sees the good in choosing sometimes mediocre paintings or ones with less finish for technical reasons. She does that I believe because she thinks such curatorial choices allow gallery visitors to themselves query the ontological questions which bedevil the definition of art as a practice. See, for instance this perception of Freud’s early work and the omnipresence in it of a curtailed but necessary narrative wonder and its later metamorphosis into something much queerer:

In Hotel Bedroom, Freud is a wary black ghost behind the bed in which Caroline Blackwood lies swollen-eyed and up to her chin in sheets. He looks at us, she stares at the ceiling. The same misery, one infers, is repeated in the window opposite.

But these narratives came to a halt, replaced with the inexplicable, tangential or mysterious. Sweep your eyes round the enormous second gallery here and the bodies seem to have fallen like meteorites to earth. Figures lie splayed, toppled, dropped, almost always tilted or horizontal. In Evening in the Studio, a vast woman has been tipped naked to the ground for no obvious reason while a clothed model sits primly sewing behind. Narrative is implied, then sidestepped.

I find Cumming’s characterisation of this contrast flawless. Her prose is not only strikingly modern (the comparison with Swiss watches in what follows for instance) but a way of grittily conveying the flesh-as-paint analogy in ways anyone could understand and be moved by:

Oil paint gradually takes over as the life force of the portrait. It appears in loose, calorific swathes, or like blood emitting from a wound. It is soft and feathery as the fur in a Titian, thick as scar tissue or slick as swatches of expensive foundation. There are passages so astoundingly decoupled from description you stare into the canvas just to witness their journey, or watch blue turn to green to dying yellow like a bruise.

And she takes the visceral nature of this into arenas not even postulated by this show’s curators but generously allowed by them because they hold back on overly biographical interest in chronology:

… the paint gets increasingly granular and encrusted, sometimes so aggressively nubbled you wonder why Freud wanted his precious substance to appear so revolting. / Perhaps the coarseness came to equate with candour.

Here we get Freud’s ‘dark side’ without any arch suggestions about the common lowness of his underlying sexual tastes as hinted at by past commentary. Furthermore, even when Cumming takes issue with curatorial perceptions – which really only appear in the catalogue – it is to emphasise an aspect that one of their number hints at in a piece (quite brilliant in its selection of basic tropes of the paintings) by Paloma Alarcό: ‘Stains, Drapery and Rags: A Meta-Artistic Reflection’.[11]

Speaking of The Brigadier portrait, the curatorial interpretation of which as the best fleshly ‘naked’ portrait in the final room of the exhibition Januszczak is so scathing, she says in a much more measured and collegiate manner:

I am not sure about Andrew Parker Bowles either, red-faced and blowsy in his brigadier’s stripes. There are passages of upholstery – the seams of a duvet, a Chesterfield’s disgorged stuffing – that hold Freud’s attention almost more than the bodies thrown down among them.

This is a good time to say, ’so much then of the values art criticism’. What Cumming highlights so much for me in the end is that the ‘new perspectives’ for this show are not ones imposed by the curators, against which straw men Januszczak rails because they differ from his own, but those they liberate from viewers. That is what she means presumably by saying that in this kind of ‘stripped bare’ curation: ‘Freud’s portraits can speak for themselves’.[12] And thus for the essays overall, by critics, activists and painters in the catalogue, there is no over-riding ideological orthodoxy. As I have already suggested, in the past a selective biographically focused story has been the raison d’être of most exhibitions concerning this artist. Recently this selectivity has grudgingly expanded to an interest into the very actively suppressed (by Freud himself) queer episodes of his life resurrected from the gossip of Francis Bacon or hints about a long stay with Stephen Spender. Rather more hidden areas – such as Freud’s putative early three-way sexual relationship with John Minton and Adrian Ryan (see my blog on this at this link) have even emerged in one minor exhibition.

In fact, the current exhibition appears to be going to allows viewers, such as I will be, to see the evidence for Gregory Salter’s seeing in Freud’s work stories that highlight the queer and marginal rather than the heteronormative and bourgeois traditional meanings often associated with him, without foisting this former view on us as yet another orthodoxy. These views are in an excellent essay in the catalogue on the resonant ‘space around the figure’ in Freud’s work and life. Salter insists that, beyond the figures of artist and his models, more tangential and ‘othered’ stories can be told of Freud’s cultural and modern psychosocial-sexual significance than that of endless tawdry bedding and begetting, about which one, rightly, has to tut in the interests of the innocent and relatively innocent, especially the children. Salter also shows how contemporary social images of HIV and AIDS and working-class lives under Thatcherism interacted with Freud’s monumental pictures of a fleshy ‘Benefits Supervisor’ or Leigh Bowery or of gay male couples in ‘pretended relationships’, in the phrase taken from Thatcher’s Section 28 of the Local Government Bill. [13] There is no argument about what Freud ‘intended’ by these intriguingly off-centre images but their strangeness (in posture and relative positioning of the figures, since one is merely a head protruding from under a bed) shows the consequences of seeing gay male relationships as a kind of posturing in the ideology of ‘pretended family relationships’ in the 1990s that also disallowed the clear representation of males in domestic and bedroom scenes:

It strikes me at this point that I may have been over-severe on Januszczak’s critical blindness to modern forms of open curation above. However, I feel less concerned about severity in pointing out the elitism implied in his view that the art of Freud is of less, rather than different, value to that of Raphael and Titian. Here Jonathan Jones gets the painter’s intention (a stated one) correct. He argues that such associations allow us to see Freud in a different, and international (if restrictedly Occidental), context:

Seeing Freud in this museum of European painting takes him out of a boringly British context. It frees his early work from parochial comparisons with prosaic homegrown artists of the 1940s and 50s and instead makes you see his affinity with Holbein, Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder. … / Five decades later, he was trying to paint like Titian. You can compare his nudes with Titian’s two masterpieces Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto, in the main collection, which he campaigned to buy for the nation. Titian’s two opulent displays of flesh pose bodies in complex interrelated groups – and Freud does the same thing in his epic 1993 painting And the Bridegroom.[14]

And this matters not only as a corrective to the use of Titian to diminish the relative value of Freud by Januszczak but also because Freud uses the extent of his viewers’ knowledge of classic pieces to insist on the blend of manipulative artifice that combines with the visceral in order to engineer what we consider as ‘real’ in everyday life, whether in a landscape or a studio portrait. Indeed, the actual level of intention to work with the example of ‘Old Masters’ is attested to in Nicholas Penny’s short essay in the catalogue before us.[15] Of more interest to me is the way Paloma Alarcό, in an essay I have already mentioned traces the studio setting in Freud to the example of Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio to argue that Freud used such spaces as ‘somewhere he could impose his own rules on reality and push things to extremes’.[16] I have preferred to express this interest as, in effect, as stated above, ‘the blend of manipulative artifice that combines with the visceral in order to engineer what we consider as ‘real’ in everyday life’. This can create highly creative respects where the painterly, the domestic and the visceral come together in a studio art that disturbs every locale suggested by the painting, as in Painter and Model of 1986-7. We could also discuss in similar ways Freud’s use of Watteau.

And the play between art and reality is not, in my view, just an art historical game but one that has a purposes for all of us, raising ethical questions about the ontology of life and death, denying the claim too often made of these qualities being opposed binaries and bringing us back to the fantastical in the very realities Freud lived through. Whether or not Freud makes moral comment by identifying one of his Sue Tilley portraits as Benefits Supervisor Resting (1994) in that the mean and abundant are compared but with great nuance in a reference to a job role on the cusp of the maintenance of class differentiations, there are ethical questions raised (if never resolved) about life and living, resting and working in this fact. I found, with even more surprise than I have as yet expressed, that Jonathan Jones has already expressed this potentiality in his review, identifying in Freud’s work:

… an ethic of art. Indeed it is a morality of life. And it surely has something to do with the fact that Freud lived when he and his brothers might so easily – as he told his biographer William Feaver – have “ended up in gas ovens”. Freud paints life in the face of death. In his 1968 painting Buttercups, a jug stands in a sink, stuffed with flowers. I’ve always wondered why Freud’s portrayal of plants always seem so sad. Looking at this, it’s suddenly clear. He pays such meticulous attention to each little yellow buttercup: this isn’t a painting of flowers in general, not even buttercups. It’s about these single specific buttercups – and they’re dying.[17]

As for what will face my best friend, Justin, and me when we visit the actual exhibition this winter, I could only repeat (but won’t) what I said at the end of my blog on the Cézanne exhibition we are seeing on the day before and will write back and say what transpired after the event. I can’t wait, actually.

All the best

Steve

Blogs mainly about Freud

Blogs that include Freud

[1] Laura Cumming (2020) ‘Gates and Portals – review’ in The Observer (online) [Sun 2 Oct 2022 13.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/oct/02/lucian-freud-new-perspectives-national-gallery-london-review-marina-abramovic-gates-and-portals-modern-art-oxford

[2] It’s a line of investigation I noticed in Jonathan Jones’ Review of The Tate Modern EY Rodin exhibition (see link for my blog).

[3] Waldemar Januszczak (2022: 13f.) ‘Paintings that sizzle’ in The Sunday Times (magazine) [2 October 2022].

[4] ibid

[5] Gregory Salter (2022: 173) “The Space Around the Figure” in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed.) Lucian Freud: New Perspectives London, National Gallery Global with Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 172 – 179.

[6] Januszczak (1994) in The Sunday Times cited ibid: 178.

[7] Salter calls this publication one ‘firmly at the lowest rung of the tabloid newspaper ladder’ (ibid: 178).

[8] Jonathan Jones (2022) ‘Lucian Freud review – the Queen, Leigh Bowery and the artist’s ex-wives stand brutally revealed’ in The Guardian (online) [Wed 28 Sep 2022 00.01 BST ] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/28/lucian-freud-new-perspectives-review-national-gallery-london

[9] Chantal Joffe in Daniel F. Hermann (2022: 183) ‘“Flesh is paint and paint is flesh”: A Conversation with Chantal Joffe’ in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed) op.cit. 181 – 184.

[10] Laura Cumming op.cit.

[11] Paloma Alarcό (2022) ‘Stains, Drapery and Rags: A Meta-Artistic Reflection’ in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed) op.cit. 153 – 156.

[12] Cummings op. cit.

[13] Gregory Salter

[14] Jonathan Jones op.cit.

[15] Nicholas Penny (2022) ‘Prowling Among the Old Masters: Recollections of Freud’ in Daniel F. Hermann (Ed) op.cit. 148 – 151.

[16] Paloma Alarcό op.cit: 153

[17] Jonathan Jones, op.cit.

2 thoughts on “The Credit Suisse Exhibition ‘Lucian Freud: New Perspectives’ is, according to Laura Cumming ‘the artist ‘stripped bare: …. Freud’s portraits can speak for themselves’. This blog starts by musing upon the nature of mainstream media art reviews but is intended mainly to contain my thoughts prior to visiting the exhibition. It is done after reading the catalogue by Daniel F. Hermann (Ed.) named ‘Lucian Freud: New Perspectives’”