According to Caitlin Haskell, writing in the catalogue for the Tate Modern EY Cézanne exhibition in 2022, the Refusés (artists such as Cézanne, Manet and Pissarro) ‘interrogated and laid open fundamental aspects of picture-making – colour, facture, finish, resolution, subject matter, cropping, compositional structure, … – to a degree that painting itself became a critical pursuit simultaneous with its creative and aesthetic ends’.[1] This blog contains my thoughts prior to visiting the exhibition in London on 29th November 2022 and after perusing the catalogue by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (Eds.) named Cézanne & published in London by Tate Modern & in Chicago by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Caitlin Haskell’s essay prefatory to the catalogue for this exhibition makes a case for seeing Cézanne and fellow-travellers in a different way. Those fellow-travellers are not or rarely named in the usual way for art history as as Impressionists in the catalogue and it feels nearer to the truth as they may have saw it about themselves to adopt the term Refusés, from the name of the Salon de Refusés, where they showed their work in defiance of the Salon which had rejected them. As innovators in painting the principle of their modernity is seen not just as a positive programme for the art of the future but also a purposive rejection, or ‘refusal’ of the critical tenets of the past over a range of issues which defined French art in the period. As Haskell says, this fact ensured that the ‘“making a painting” became a questioning and analytical activity to such an unprecedented extent that it changed key aspects of creating and consuming art’.[2]

If the Salon, which, since its institution by Louis XIV, had stood for the values of the great French art of the past insisted on ‘smoothness’ and ‘finish’, then these painters insisted on making incompletion part of the project of painting in a number of ways: in the deliberate show (or at the least visible signs) of the painting’s process of being made such as visible brush-strokes, layered impasto or patches of untouched surface. As a result of this characteristic, a brush-stroke often had multiple significations in a Cézanne painting. Caitlin points out that Cézanne’s ‘treatment of the brushstroke as a discrete, constituent mark’ was merely one of the many ways in which ‘multiple elements in a painting by Cézanne signified multiply, and they did so across frames of reference’ (such as the demand for ‘finish’) ‘that earlier styles of painting had elided into a single entity’.[3]

It is probably clear by now that this exhibition is a cognitively led one that demands that we see the painter again and ANEW but not in cognitive terms alone. However, it also relies on evidence from Cézanne’s biography (particularly the circular journeys between Paris and Provence) and the reported views of his contemporaries too, especially Camille Pissarro (who knew him best). I rather like this aspect of the catalogue since the aim is also to rescue how we see the art of the period (and not just Cézanne) from the purely art historical trap that has grown up around them. It does the latter in two ways: first by prioritising the fact that the analysis of art, using both objective imaging technology as a major tool in one essay precedes analysis of the evidence from letters and other documents; second, by emphasising the range of the immediate responses to art that require analysis, particularly those of haptic and proprioceptive sensation beyond the merely visual; and, third, by interspersing the catalogue with subjective ‘takes’ on particular pieces by artists working in the current moment and giving them as much attention as to ‘art critics and / or historians’ or Cézanne’s contemporaries. In relation to the latter however, excellent use is made of both their failures to understand Cézanne and their sheer wonder at his achievement and their difficulty in fully comprehending it in relation to their own ideologies and methodologies.

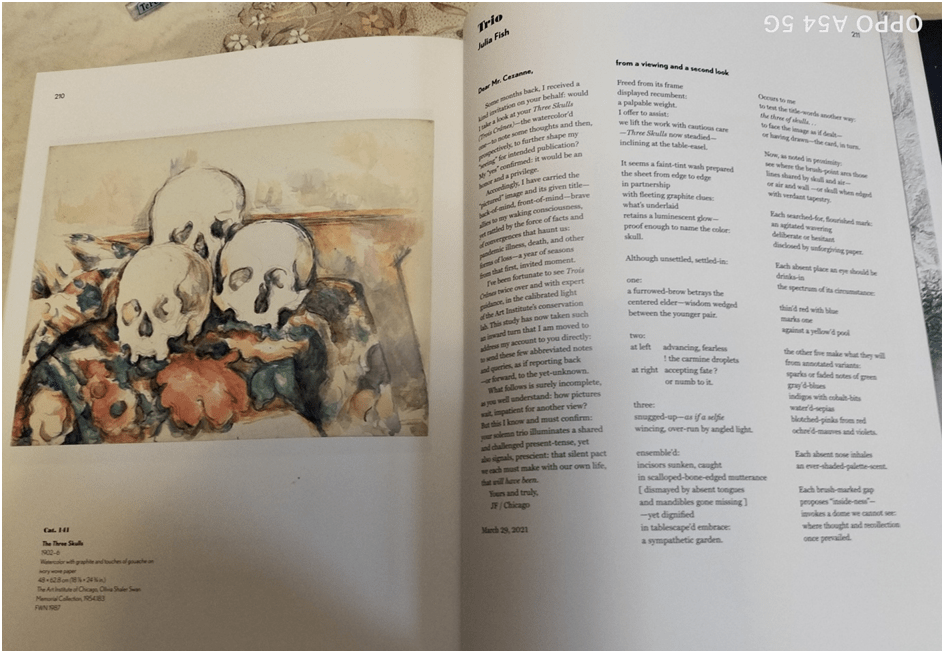

Of the artists currently working their take is allowed expression that defies the demand for immediate transparency, which mirrors in my view, Cézanne himself, so that Julia Fish responds in verse with rich perception:

Each absent place an eye should be

Drinks-in

The spectrum of circumstance:

…

Each absent nose inhales

An ever-shaded-palette-scent.[4]

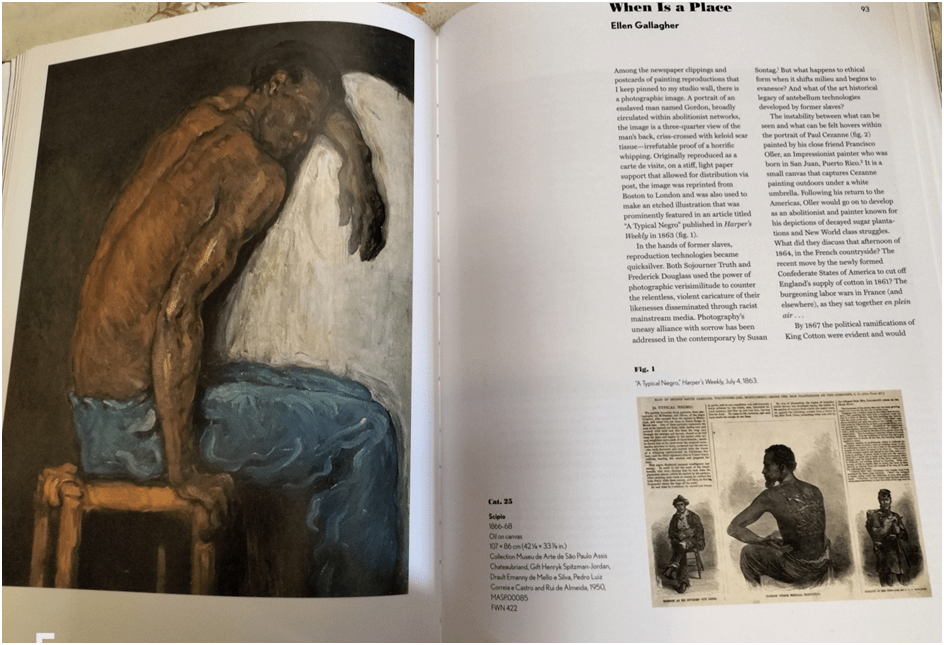

Lubaina Himid,in a frankly subjective manner, recreates a narrative from Cézanne’s early and strange homage to Manet Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. In this painting, she sees ‘meaning’ and event as both an immanence and as freshly present: ‘The paint seems to be still wet and the scene feels as if it could be altered’.[5] In complete contrast Ellen Gallagher, who has subverted everyday racist tropes in her art, returns to recreate a piece of history suppressed from the norm of art history to show how Cézanne made immediate what was not only the mediation of racist thinking and stereotypy in the popular imagery of his own time. It is seen as an achievement of art less well expressed at any time but felt, wherein we find in the incarnation in paint of Scipio as a response to images such has that of ‘A Typical Negro’: ‘ The liquid plain of painting hinged to a corporeal past that is not past. It is no wonder Claude Monet kept this canvas and never let it go’.[6]

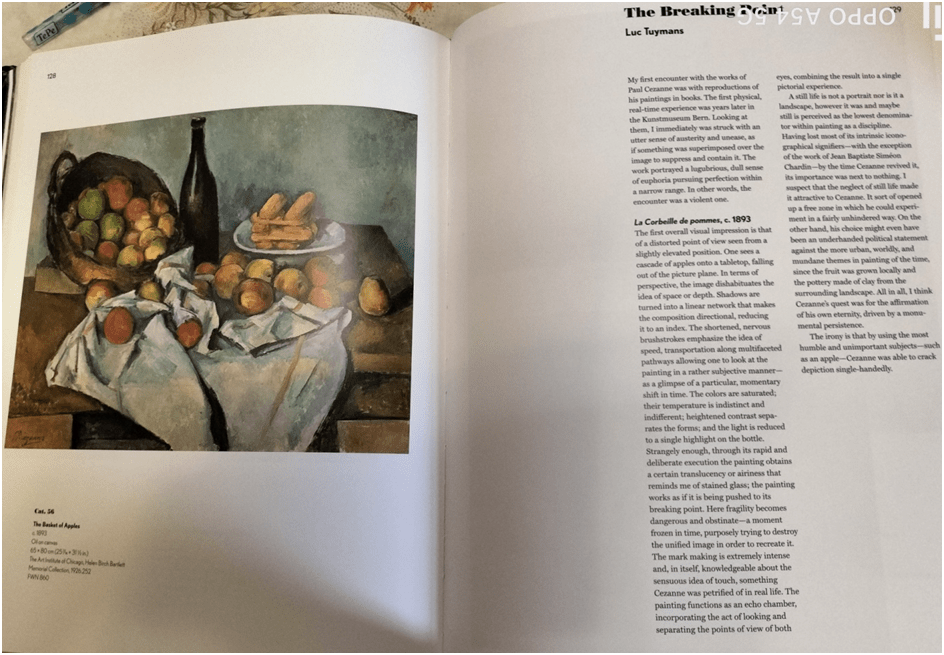

Each artist queries the way in which Cézanne’s paintings address contemporaneous issues that belong to both his and their time in history and sometimes show that those issues are in fact ones that are true of the continuum of time between both periods of history. There are too many artist-based critiques to point to all; however, my limited choice of examples is not therefore a critical decision made by me but rather one based on showing the variety of commentary, each of which betrays peculiarities of interest or point of view of the modern artist commenting on Cézanne’s method or way of seeing the world. The most ‘objective’-seeming commentary is by Luc Tuymans. However this piece still makes bold leaps that read beliefs about Cézanne from the painting, which are then used to comment on the painting itself as an object. It is a fairly circular form of thinking that bears in it certain beliefs about the subjective nature of art itself: ‘The mark making is extremely intense and, in itself, knowledgeable about the sensuous idea of touch, something Cézanne was petrified of in real life’.[7]

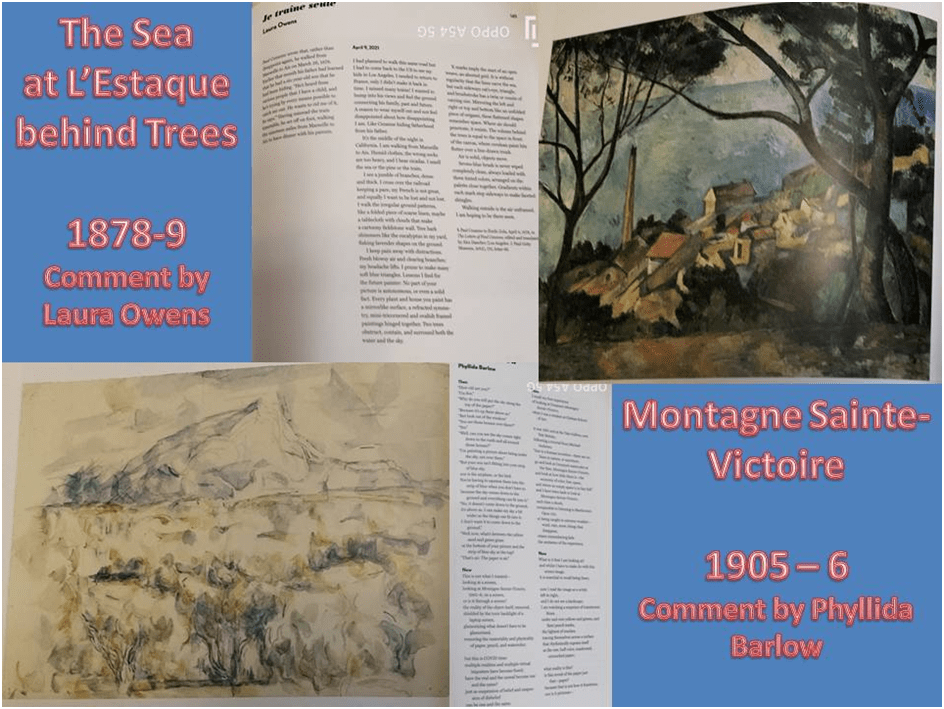

Laura Owens addresses Cézanne in speaking of The Sea at L’Estaque behind Trees directly saying, ‘Lessons I find for the future painter: No part of your picture is autonomous, or even a solid fact’. Driving this kind of commentary forward allows her to show strange contradictions between her perception of the painting and conventional thinking as she imagines herself walking the ‘same road’ as Cézanne:

Air is solid, objects move.

…

Walking outside is the air unframed.[8]

Phyllida Barlow has always expressed herself in multiple media. Her comments in a long verse poem addresses the use of blank space made from the paper exposed between marks of paint in a Cézanne watercolour of Montagne Saint-Victoire. She argues that this says a lot about what any medium of art can, and what it cannot, say – whether in words or marks on paper:

the exposed paper refuses definitions and rebukes language

but embraces the ambiguities of anticipation and namelessness:

I might ask, “what is there?”

but there is no reply.[9]

The critical address of this exhibition and the essays in the catalogue has no unifying intention. The aim of all the essays is I think to show us that Cézanne organized the chaos of multiple ways of looking at art and its relation to both the art of the past and the art it makes possible in the future: ‘the way he transcribed his experience of looking at the world for others to share’.[10] The idea of sharing experience then that cannot be easily communicated in a manner that is direct and not, in its essence, ambivalent and unambiguous is central to this critical review. It explains why ‘refusal’ is such an important concept for Cézanne, just as Caitlin Haskell argues (as we have already seen). This terminology of refusal covers not only his constant experience of being refused by people and institutions that thought themselves to be authorities but also his insistence that he used his art to ‘refuse’ to collude with the idea of ‘tradition’ in these institutions, even the newly formed ones of his own circle, or the directions in which they wanted to take the art of the future. This is why Gloria Groom sees him as challenging Manet, ‘the unsurpassed painter of modern life’ as much as he did the Salon in order to avoid ‘being reduced to an Impressionist pleinairiste’ and to ensure that, even though others may use his way of seeing and painting in the future, they would ‘fail to capture precisely how he achieved his particular way of seeing, of perceiving’.[11] Caitlin Haskell’s essay is so rich I will not further simplify or reduce it here but this one essay alone has helped me to look forward to this exhibition as if it were of an artist I have never seen, rather than one that has intrigued me many times – whether in paintings seen in the flesh or in books.

In all honesty the perceptions of Kimberly Muir and colleagues are clearly central but demand looking at again when I have seen the original pictures. These collaborative authors utilise modern imaging techniques as part of their evidence for an argument with similarities to the others writing in the catalogue. It is an impressive essay that uses imaging in ways that differ from its role in the armoury of the ideas in the connoisseurial tradition. This essay analyses imaging from different techniques in order to show the complex morphology of the finished paintings and some of the hidden signs of their facture. These signs, both hidden and in plain sight, nevertheless still ‘draw the viewer’s attention to the process of painting (my italics)’.[12]

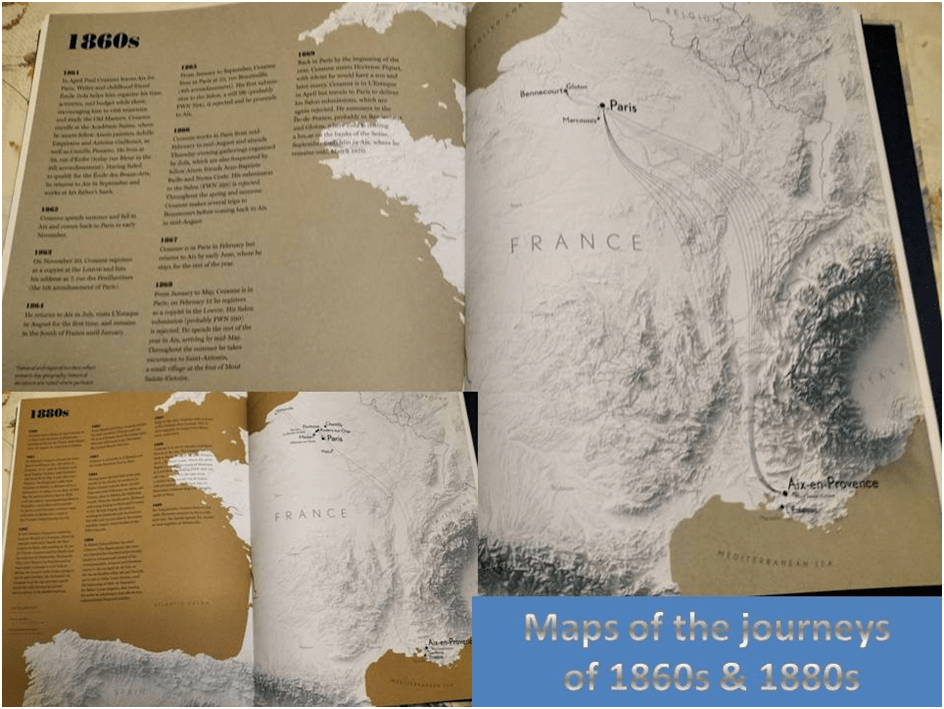

The final longer essay by Natalia Sidlina in the volume is a fascinating exploration of how the tension between a cultural capital such as Paris and a cultural region with autonomous features like Provence helped to define the way forward for a painter looking to redefine painting itself.[13] His constant shuttlings between capital and province are illustrated in pages of maps produced by Kathryn Kremnitzer charting his journeys, especially his repeated retour au pays to refresh the vision which neither the region nor the capital truly appreciated during his lifetime.[14]

Of course I write these preliminary blogs to look forward to seeing the exhibition, which for me and my friend Justin Curley will be on the 29th November 2022. This catalogue however has, like no other I have consulted, made this more than an exciting and challenging prospect because in honouring many perspectives on Cézanne, it honours mine and Justin’s in anticipation of them. It will mean that our conversations at and beyond the exhibition will be rich for we will have to consult not just the ideas but the sensations and feelings that make the experience of great art a tremendous gift for each of us, but those that grow from the conversation itself. The pictures I am looking to look at anew are many, partly because I have loved them only from the evidence of reproductions. What will my experience be? What will Justin’s experience be? What will be our experience of sharing those experiences with the help from imaginings of them in the catalogue? What parts of Cézanne will we now know and how? I will write that up later either as an addendum or new blog.

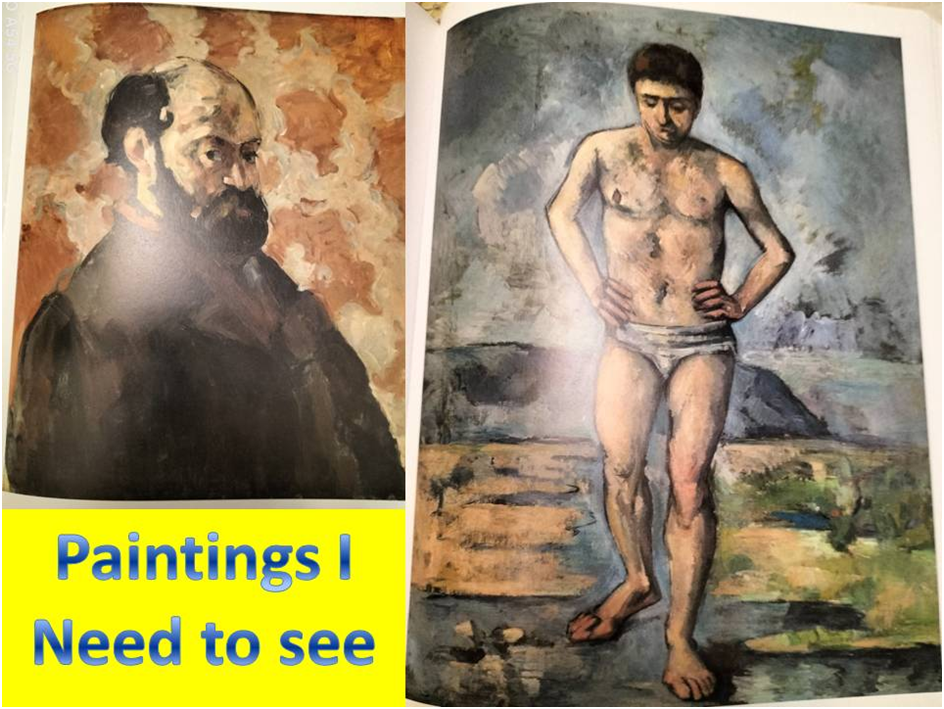

Amongst the many paintings I will look forwards to personally are, amongst many others, The Bather (a male nude I admire above many others by many painters) and this tremendous self-portrait which shakes the boundaries between how we disclose and enclose complex selves.

So I will be back on this subject.

All the best

Steve

[1] Caitlin Haskell (2022: 35) ‘Cézanne’s Refusal’ in Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (Eds.) Cézanne London, Tate Modern & Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 35 – 45.

[2] Ibid: 35

[3] Ibid: 38

[4] Julia Fish (2022: 211) ‘Trio’ (on Cézanne’s The Three Skulls) in Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (Eds.) op.cit., 210f.

[5] Lubaina Himid (2022: 77) ‘The Breakfast Picnic’ (on Cézanne’s Luncheon on the Grass) in ibid: 76f.

[6] Ellen Gallagher (2022: 94) When Is A Place’ (on Cézanne’s Scipio) in ibid: 92 – 94.

[7] Luc Tuymans (2022: 129) ‘The Breaking Point’ (on Cézanne’s The Basket of Apples) in ibid: 128f.

[8] Laura Owens (2022: 149) ‘Je traîne seule’ (on Cézanne’s The Sea at Estaque behind Treees) in ibid: 148f.

[9] Phyllida Barlow (2022: 196) ‘Then and Now’ (on Cézanne’s Montagne Sainte-Victoire) in ibid: 194 – 196.

[10] Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (2022: 18)’Organized Chaos: Looking at Cézanne’ in ibid: 17 – 21.

[11] Gloria Groom (2022: 26 & 31 respectively) ‘“At Once Unknown and Famous”: Cézanne in Paris’ in ibid: 23 – 31

[12] Kimberley Muir, Kristi Dahm, Giovanni Verri, Maria Kokkori, & Clara Granzotto (2022: 57) ‘“A Harmony Parallel to Nature”: Color, Form, and Space in Cézanne’s Watercolors and Oil Paintings’ in ibid: 47 – 57

[13] Natalia Sidlina (2022) ‘Cézanne’s Slow Homecoming’ in ibid: 61 – 67

[14] Kathryn Kremnitzer (2022: 218f. & 214f. respectively in picture) ‘Mapping Cézanne’ in ibid: 217 – 223.

10 thoughts on “According to Caitlin Haskell, the ‘Refusés’ (artists such as Cézanne, Manet and Pissarro) ‘interrogated and laid open fundamental aspects of picture-making – colour, facture, finish, resolution, subject matter, cropping, compositional structure, … – to a degree that painting itself became a critical pursuit simultaneous with its creative and aesthetic ends’. This blog contains my thoughts prior to visiting the exhibition in London after perusing the catalogue by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell & Natalia Sidlina (Eds.) named ‘Cézanne’.”