‘… how there’s still a kindae / fuckin serious / / as fuck / splendour / / tae every minute ay aw ay this? ’[1] This blog contains my personal views of Jenni Fagan’s (2022) The Bone Library Edinburgh, Polygon.

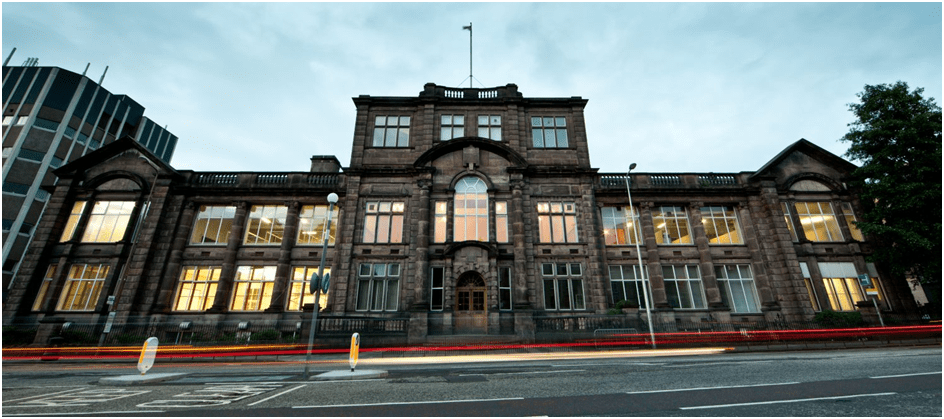

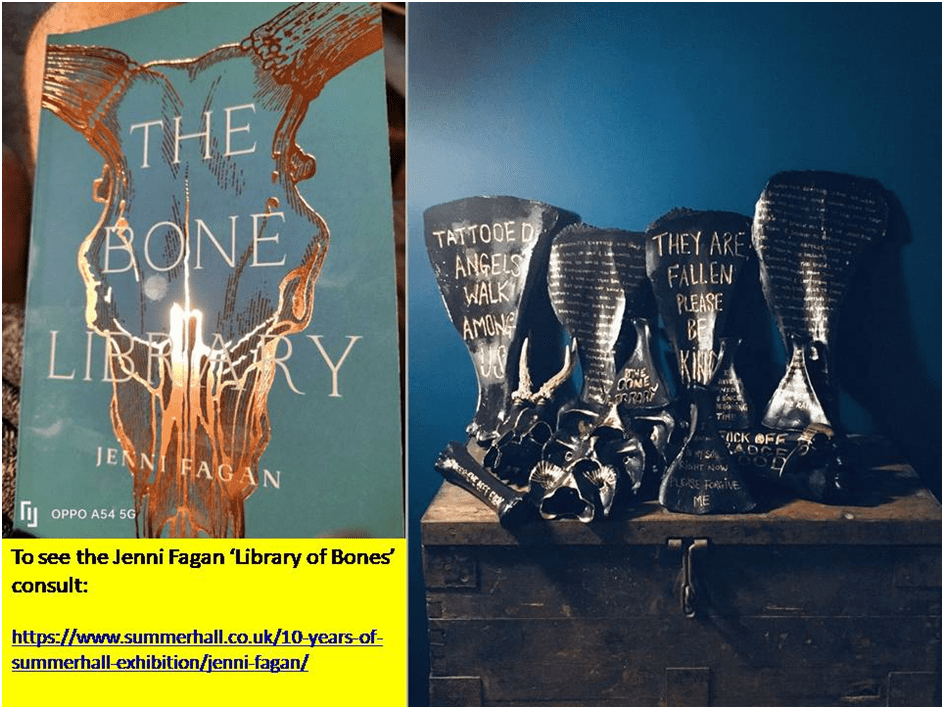

Jenni Fagan’s single works reflect on each other. This is not because she writes on the same topics in each work (nothing could be further from the truth) but because she deals with themes so fundamental that they cannot be exhausted in one articulation of that theme. Sometimes the difference of articulation is one of the medium chosen but sometimes it is because the manifestation of the theme shows that multiplicity of effect runs through basic topics like the care and support societies offer to vulnerability in the development of persons, animals and communities. In this case the title of this collection recalls the sub-title of a chapter of her last long novel, Luckenbooth (see my blog at this link). In that novel, the character, Levi, a young black man from Louisiana in 1939 tells, apparently in writing addressed only to his ‘brother’ back in the USA, of his employment in ‘the bone library’, where he ‘catalogues animal bones’. Levi is fascinated not so much by the Royal School of Veterinary Studies as an institution, which in 1935 became part of The University of Edinburgh, as in the architecture of its home in 1939 and the personae who work there with him, which he describes under the name of its founder (in 1823), William Dick (1793 – 1866) as ‘the Royal Dick veterinary building’.[2]

In 1939 The Dick Veterinary School was housed (from 1906 to 2011) at Summerhall, the beautiful building that is known now as a key venue of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Its story is told in the University’s website.

The description of the building by Levi is haunted by the college students’ daily anatomical dissection of animals – exotic or otherwise – and the proximity of the presence of decay and the excremental with transgressive learning. Even 10 Luckenbooth Close, the ‘tenement’ at the centre of the story and Levi’s home,, is connected to the underground catacombs he imagines transporting human bodies to the University Medical School for anatomical dissection. Human and animal aren’t always differentiated. Although Levi (his ‘middle name’) thinks himself a philosopher he is aware that his mother called him by his first name, ‘Wolf’: ‘I’m more of a philosopher than a wolf – more of a Ptahhotep or Plato or Aristotle’.[3] If dissection fragments bodies, Levi (the philosopher) becomes more interested in reconnecting them. M. John Harrison, in a review in The Guardian, describes his story in Fagan’s novel thus: ‘He is learning to connect them, while impulses he doesn’t understand compel him to build a mermaid skeleton’.[4]

And however Gothic is the imagination of Levi with regard to the silence and secrets that the structure of many rooms in complex architectures facilitates, his relation to the purpose of the Summerhall College is in his function as part of the scientific process that lies behind the study of anatomy in the college. It’s a process that starts with the dissection of a range of ‘subjects’, exotic or otherwise: ‘a zebra, two cows, one bull, a gazelle, and a bear – …’. That is I think because it is the same process by which Wordsworth imagined the threat of science to the imagination of what we see in nature, but perhaps too in super-nature, that starts by the visceral elimination of life from that which we observe and report in life-sciences.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.[5]

The products of dissection are then boxed, ‘filed’ and sorted ‘numerically by size and species’ by Levi. In effect Levi that it might be dissected, categorised and the knowledge stored in an alien, and essentially unliving (rather than just dead since it pretends to life) system.[6] To the idea of files that dissect we will return in this blog, in relation to main themes about life-science, and especially life-science and the contribution of boxing and filing to the marginalisation of some lives, especially those of the ‘ootlin’. However, my first concern is to look at the overlap between the story of the Dick Bone Library in Luckenbooth, as mentioned above, and in The Bone Library volume, particularly in the central long narrative poem, Mary Dick and the shorter The Bone Library.[7] For even the writer is fragmented on arrival at the library:

I was in bits

When I arrived here!

I was in so many parts[8]

The longer narrative poem takes on a story and the name of a person already pointed to by Levi in Luckenbooth. Levi’s story is strange in that it speaks of the Dicks, boss and sister as contemporaries though they lived and performed those roles some hundred years before Levi’s story.

Mary Dick is the boss’s sister. She’s the one who really keeps this place running, nobody wants to disappoint her and if anyone is disgraced it’s her office they have to go to and nobody wants to do that – she’s quite a woman, I like her a lot. Mary founded a scheme to treat the animals of poor people free of charge and it makes me glad to see animals go out mended.[9]

The poem Mary Dick is equally ghostly. It is a poetic autobiography of Mary but told after her own death by a consciousness surviving that event, her role in preserving the memory of her brother William and dedication to education and the cause of the poor and marginalised. In the poem she attributes the idea of treating the animals of the poor to William. The awe with which she was treated by students as a moral guardian, disciplinarian and model of female behaviour is also mentioned. The poem dwells on Mary’s ‘ardent / Liberal’ politics and support for a Free Church, if Calvinism can ever to be thought free, and wider suffrage. The stress for Mary though is on ‘learning’ and the possession of knowledge, with only a dream concern with actual ‘practice’ in and on the world. In brief, the object that she pursues is never one in her own possession or used for her own gain but one that is the preserve of a series of men. Indeed part of her role is to ‘tae preserve ma brother’s / extraordinary legacy’.

As Mary discovers, when a talented woman supports, sustains and maintains the memory of male knowledge and makes use thereof, she, at the same time, excludes herself from its practise in the world, though she pursues its values, transmits them to others (to male others at least) and makes its memory endure and its value felt: ‘take what he hud learnt / put it intae practise / and even more important – / pass his knowledge on’, whilst equally sustaining her own rightful exclusion as a woman from that knowledge.

I studied an observed

In no small way

Alongside

Those men

Fir aw those years

I hud knowledge

but I could

not practice,

however I mentored

thousands so

at least they –

could …

I hope it’s clear that I find this narrative poem extraordinary because it takes as its subject the relationship between women and their relationship of longing and exclusion to knowledge and practice in the world. Mary’s role is constrained by her gender and this story emphasises that with the same ‘quiet – certainty’ that she herself claims to have in her assertion that ‘a life kept busy’ such as her own ‘is a life lived well’. A woman like Mary Dick bears the sign and burden of knowledge and professional training that is held only in trust for the men it empowers and for passage back to them. She, as we have seen, preserves her brother’s ‘legacy’ by holding his knowledge and power in her head, passing it on to younger men so that they practice from it and gain they more of the real power and wealth of which she has no personal hope of using and from which she will profit.

She tells her story as the story of one who supports and motivates the story of male endeavour. When she hears of Alex Gray going to vet college, ‘I telt ma clever brother / it wiz time he did the same’. As William begins ‘the exceptional / practise of healing disease’ , she ‘wiz at William tae learn / as much as he could / tae teach me, …’. But to know and not to act in ways that applied her knowledge makes Mary Dick a kind of silenced and invisible hero, whose self-assertion exists to convince only her of her worth: ‘I can say that I did aw / that an mair, / with a quiet – certainty’. The tone convinces us not only that is she knows with certainty (however modified that certainty be by pause preceding it) but only at the cost of being ‘quiet’ about her achievements in the public realm. What is clear is such a life is won by preserving her unmarried and chaste state by ‘keeping her first floor ‘bedroom’ window ‘firmly – shut’. This is a thoroughly assured poem because of the certainty that ids needed in women of their own worth but of the oppression that makes them silent about their own achievement in contrast to those of men. And under that silence is a sense that knowledge is of value only when used to heal and support the marginalised and equally silent:

I still kept up ma knowledge

of the issues

of the day,

especially

those that affected

the poor

or those in pain.

It is a beautiful poem I’d say which performs before our eyes the repression not only of women’s knowledge acquisition and sharing but of hope which might lead on to a future beyond its silent, controlled reserve. In this sense it reminds me of Hex (see my blog at this link) and its definition of a witch as ‘just women with power and skills and an innate knowledge’.[10] This theme is however a reflection too of a concern with the effect of male knowledge and its practices in a social world that professes to care and support its inhabitants. In a world of male-defined evidence-based practice, the concern has been not with the subjective feelings of those who attempt to life but with a defined notion of objectivity. This is why Levi turns to the construction from dissected bones of a new kind of supernatural life in his mermaid. The theme is best represented with the concern with a kind of knowledge that can be symbolised in and validate by the experiment, as used in the natural and social sciences, especially in social psychology.

This theme was first apparent in The Panopticon whose narrator and subject, Anais Hendricks sees herself as ‘AN experiment’ or as in an experiment that sets and controls the parameters of her life and varies the events to which she is subjected.[11] She is oft the ‘subject’ of the kind of experiment whose behaviours are observed, noted and compared as a means of measuring the effect of a series of independent on them, as if they were the dependent variable of the experiment and recording its measurement and other data in ‘reports’ that are then ‘filed’. However, perhaps this way of writing out her life is the only source of significance her life contains:

I wonder if the experiment have a little gadge typing it all up – everything that happens to me. Maybe they’re faxing back reports, every sixty seconds.

Anais Hendricks’s eyes looked to the left – 11.06 a.m.

Anais Hendricks inhaled – 11.07 a.m.

Anais Hendricks took a long shit – 11.13 a.m.

Anais Hendricks is bored – 11.17 a.m.

What if there is no experiment? What if my life was so worthless that it was of absolutely no importance to anyone?[12]

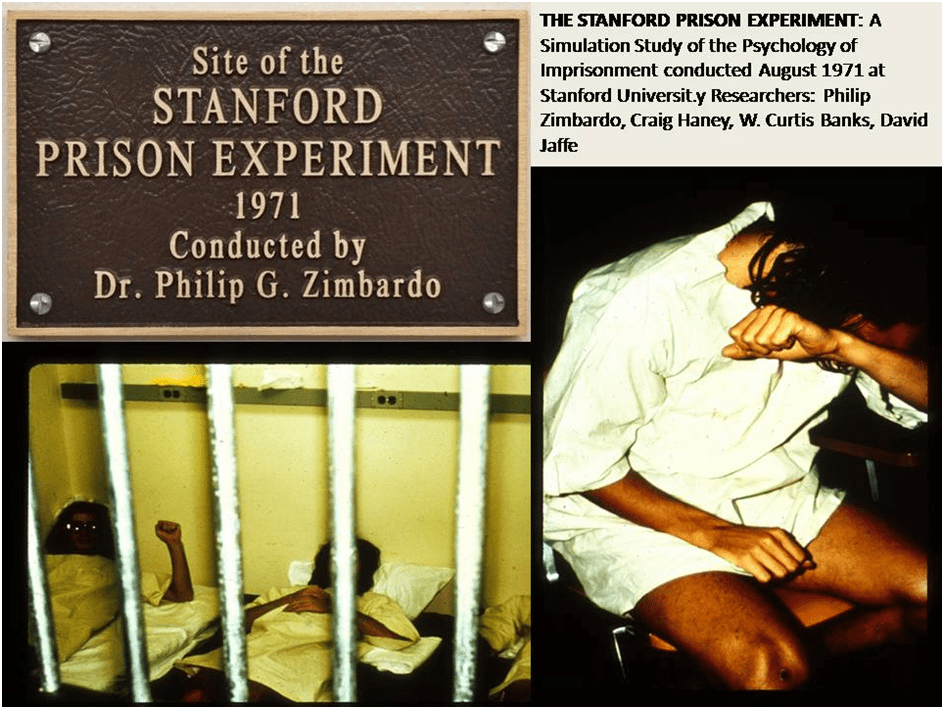

This concern with the external dynamics of the experiment runs throughout Fagan’s work. At this point I see lecturers in foundation psychology hammering on my door to explain with a superior air, for this is how I saw it done in the Open University, that these are not the basic features of an experimental method rather of an observational one, but they look very like the practices of the social psychological experimentation of which a clever young woman like Anais would have been aware – such as the work of Philip Zimbardo in 1971 known as the Stamford Prison experiment (and his mentor Stanley Milgram) which uses observation (participant and otherwise), records and recording in ways that Anais feels subject to. Such experiments strained the boundary too between fictional and real roles in being themselves on ‘simulation’ of real situations whilst self-consciously being enactments, examining the systems which shaped identification for the experimental subject. To simulate soon become an access to the ‘real’ situation and these are precisely the parameters between which Anais’ consciousness of self floats, although she, with her contemporary inmates of the Panopticon children’s facility, simulates the possibility of an unconstrained life rather than the opposite.

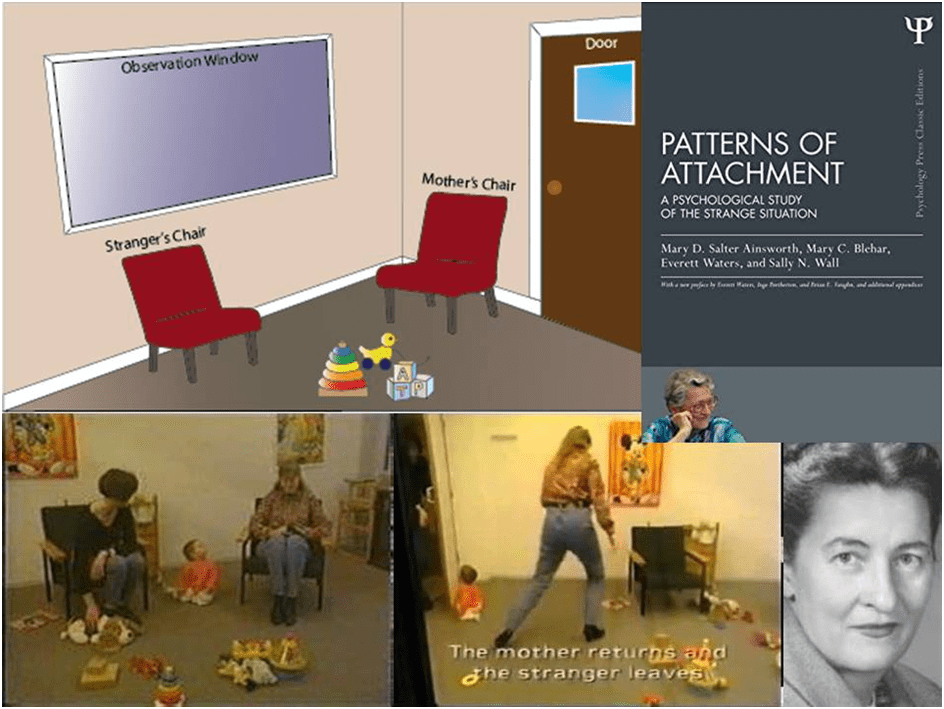

Even more significant are the experiments involving simulation via which Mary Ainsworth and others experimentally simulated the conditions addressed by attachment theory – reproducing and explicating the bonds between a child and its main caregiver – first proposed by John Bowlby. The notion that bonding was a variable dependent on the variation of several independent factors, whose outcomes could be observed in simulation, is as near as we get to the kind of experimental subject that Anais feels herself to be. The name of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation ‘experiment’ tells it all. It simulates the effect of estrangement from a primary love object by varying, under standard conditions the presence, absence and co-presence of that primary caregiver, inevitably nearly always a woman and mother at the time of its common use and replication in academic research and therapeutic assessment, and a ‘stranger’ to whom the child has no preformed attachment.

Yet the manipulation of a child’s environment in order to study varying levels of comfort and distress is clearly disturbing if the child’s powerlessness in the strange situation is considered. However, my experience of teaching these ‘experiments’ over many years is that do not raise the levels of distress felt by learners in considering some of the animal variants of the ‘strange situation’ and especially the radical ones of Harry Harlow, with new-born or infant rhesus chimps.

This experiment forms the subject of a poem in this volume (Monkey Love Experiment on pages 71-72), which narrates the story of Harlow’s experimental procedure and constantly translates issues of ‘objective’ (as they like to call it) scientific curiosity and the ‘academic gaze’ into the responses of someone more self-interested who can be said to be ‘smugger than Satan’ when experimental hypotheses are proven. Harlow refuses to intervene into the distress he observes as an outcome of the experimental manipulations he also performs, refuses to imagine the experimental subject’s mental operations and is a ‘cruel fuck’, an example of the ‘depth of man’s idiocy’. These judgements based on performative compassion (and an equally performative hating of the absence of that emotion in powerful men) have not been favoured in poetry since the time of T.S. Eliot and F.R. Leavis but here they are demanded precisely as a means of measuring one’s distance from the search for the ‘objective correlative’ of an emotion in the manner of an art that distances itself from direct expressions of abstracted feeling. But purposively to the latter this poem tends, addressed as it is to ‘Monkey 105’:

Every day I would have carried you pouch-to-pouch, gig-to-gig,

I’d have let you sleep on me,

Your tiny hands wouldn’t even have to hold on.

I’d not have let you go.[13]

This might seem to be a rhetorical flow of subjective emotion, outstripping any concrete communication, but is not. It strains in fact to define ‘attachment bonds’, the very core of the ‘experiments’ from which it springs, in terms of an imagery of love-in-action, which holds it subject in the very communication of what holding is, a conveyance in safety of the vulnerable by the caring. The pouch feels to me to capture the kangaroos’ means of holding its offspring – often invoked in the animal analogies of attachment, the ‘gig-to-gig’ the story of a mother exposed to public exhibition carrying her child with her between events. None of it is very clearly conveyed. It cannot be for it is the thought of a loving caregiver who holds on to her child whatever the circumstances and regardless of self-definition as mother or some such alternative caring agency.[14] For Harlow was wrong about the focus on motherly responsibility for the infant ‘didn’t even know what a mother was … far less that she had a right to it’ in Fagan’s words. The little hands that do not have to ‘hold on’ by their own agency recall the rhesus infants clinging to the terry cloth mother in Harlow’s experiments as seen above.

In brief, I believe the aim of this poem is to expose the emptiness of emotional content of a supposedly objective and scientific study of love and caring between the enabled and the powerless – the child or animal or child-animal. It is tempting to see this antagonism to the ‘evidence-based’ science of caring as autobiographical and there are commonalities across the works and a memoir soon to be released by Fagan based on the cold social work files of her history of being-‘cared-for’ in institutions but that would be reductive. These ‘files’ are addressed in a brief poignant lyric On The Files (page 9) – for these files mark an absence of possible attachment telling that ‘nobody knows ‘ where I lived / for the first three months / of my life’ (three months is the critical period for attachment formation in Bowlby’s original thoughts on attachment).[15] For Fagan, I believe, will painfully expose herself in this story, as another story which tells of the loss of love in the science supposed to define both it and the welfare of those made vulnerable by the circumstances of their environment including environmental relationships. More of it is told in poems like The Truth is Old and It Wants to Go Home about un-fostering foster mothers (page 13). And anyway even if true creativity cannot be contained or held in ‘science’ alone, it is what science needs to serve for science is more than men think it is: for ‘science in no way negates / a true witch’.[16]

I begin to make sense of this poem by seeing its object in the comparison of caregivers – between the ‘cruel fuck’ that is Harry Harlow, intentionally or otherwise for he believes his role to be prescribed by institutionalised ‘academic science’ to the accidents that made Mary Dick a carer despite the patriarchal institution her loving served. That reflection is what makes Fagan’s very personal attack on seeing the discoveries and labels used in biological science as if they were definitive of the relationship she made, and continues to make with her son. They aren’t. She uses scientific terminology in ‘I’m Not a Fossil, you Are a Curio’ (ibid pages 1-3) to deny that the language of genetic inheritance contains or determines either the relationship or its outcome – may favourite piece being the side swipe at ‘gender-critical feminism’ and the patriarchy it paradoxically allies to itself here (as I – possibly perversely – take it to be):

My dear sweet toxic male gene,

What’s your fucking issue with humanity

I raise one of yours and he is fuck all

Like so very many of you,

…[17]

The poems continue to define unlikely love of the vulnerable (and sometimes unlovable), such as that to a slug in The Nineteen Thirties House (page 4-6). And we have to remember that one of the unlikely to receive love and care, even from ourselves IS OURSELVES. Yet:

Well – I won’t revoke

My expectations

Of being cherished

Just as I am.

Just like this.

Sin-fucking-cerely.[18]

I know but cannot refind (yet) that a ‘cloth-mother’ is mentioned in another poem (I will revise this if found again) linking the giving and receiving love to the Harlow experiment. Artists too are sometimes the unloved and are symbolised in those experimenters in the new Summerhall building and to them we are exhorted to ‘please be fucking kind’.[19]

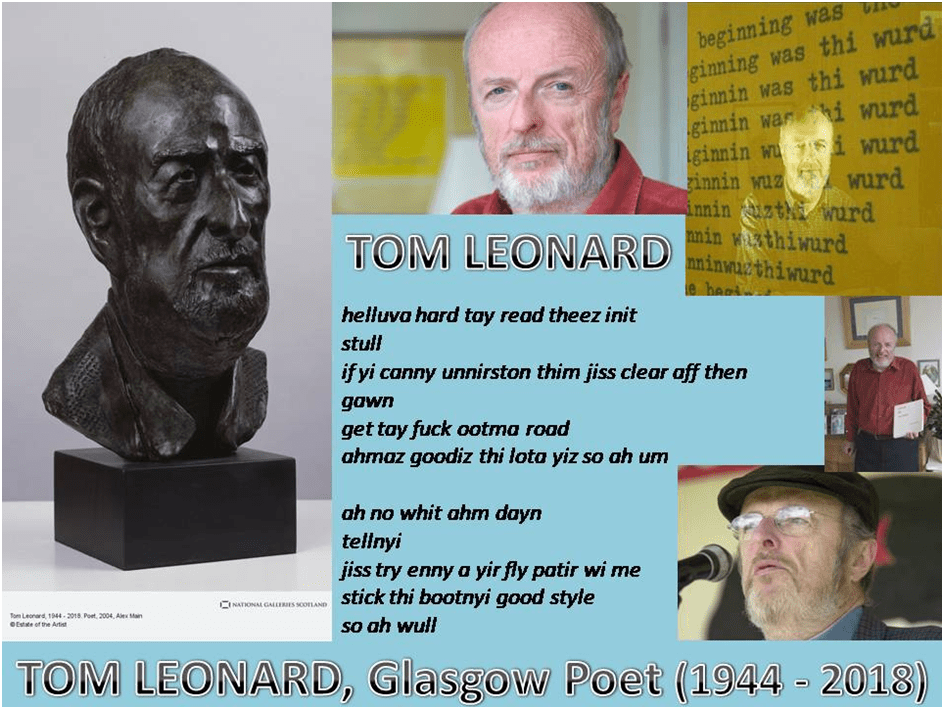

There are so many beauties and wonders in this new book. I will end then by just referring to the favourite that I use in my title Fir Tom Leonard (pages 27 – 31). I do this because this is a poem on the cusp of others I do not write about (such as those dispersed amongst the collection about art and artists, including that appropriately surreal production called Who Did Duchamp [pages 36 – 43]) and which cannot be press-ganged into the constrictions of my readings of Jenni Fagan’s poems thus far. They are ALL more than they say they are and, in being thus, play games with ideas of the ontology of loving states which are as complicatedly fake as Penrose stairs.[20] Tom Leonard, the Glasgow poet, died in December 2018 and is the addressee of a poem about the very ‘beauties and wonders’ that might go unnoticed without poets to notice and love their oddly contradictory natures somewhere between beauty and the ugliness of social injustice. The beauties of the work about which Tom is asked ‘d’ye ever hink’ are barren, like ‘the desert in Egypt’ that is one of her examples but lighted by something remaining of the beauty a poet would observe in them would they be looking, such as prostitutes: ‘wummin plying their wares / when they used tae just be girls too …’.[21]

There is something wonderfully true in this poem I believe about the fact that the fate of potential to beauty, in humans as in art, is not a thing merely that gets lost in itself or in its deeper significance in history and personal development, like the colours of fish that are hard to see and which too see with difficulty and the fate of ‘death wish / comets’ that are ‘racing each other into oblivion’ in ‘dark matter’ that ‘fucks us like eighty to one’.[22] This poem travels vast distances in time-space, From Spain, France, to Egypt, inside small spaces from basements into ‘jars’ and an ‘old tea tin’, vast underwater terrain in the sea and then into ‘space’ itself. Yet there is beauty even in ‘wee bars’ where ‘two people drunk an holdin ontae each other / like everyhin is in their arms at that minute’. This is the potentially sordid awoken into potentialities of hope and love about everything. Such wonder lies in the life and death of elephants, or in the taste of salt on a loved one’s skin. And finally that hope lies in everything we ‘owe’ to the new-born. These must learn, as we have done ‘tae no trust the agents ay this earth’ but at the same time realise, as Leonard’s and Fagan’s poems make available:

… still a kindae

fuckin serious

as fuck

splendour

tae every minute ay aw ay this? ’[23]

What Jenni Fagan has learned from Tom may well be that associated with her own art created in the Bone library in Workshop, Day One (ibid: 20f). Fagan carved her poems onto unwanted bones from the Bone library – materials wanted the more by her because they were unwanted and dubbed inferior:

I was informed

they were inferior bones

which only made me

want them more.[24]

Things lost to death are transformed by Fagan’s art, even though ‘the reek of burning marrow / kept the workshop guys far away’ and took away their appetite and breath, into something beautiful that burns even in the cold snow of the Summerhall courtyard.[25] These bones were found in boxes, ‘neatly labelled / numbered in the attic’.[26] Were they the ones filed by Wolf Levi: that character in Luckenbooth, cited earlier in this blog? The imagination of great artists spans time and space and in time-space what looks ugly, like the products of patriarchal capitalism, might have the potentiality of its useful beauty and truth revived and ‘bow to nobody, be free’.[27]

Jenni Fagan is a great poet. Read this volume and be addressed as I was: ‘Come on queer thing!’[28]

All the best

Steve

For other blogs by me on Jenni Fagan’s work as artist and teacher see:

[1]Jenni Fagan (2022:31) ‘Fir Tom Leonard’ in The Bone Library Edinburgh, Polygon, 27 – 31.

[2]Jenni Fagan (2021: 32) Luckenbooth Richmond, London, William Heinemann/Penguin Random House.

[3] Ibid: 34

[4] M. John Harrison (2021) ‘Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan review – brilliantly strange’ in The Guardian online (Fri 15 Jan 2021 07.30 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jan/15/luckenbooth-by-jenni-fagan-review-brilliantly-strange

[5] William Wordsworth (1798) ‘The Tables Turned’ Available in: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45557/the-tables-turned

[6] Jenni Fagan 2021 op.cit: 33

[7] Jenni Fagan 2022 op.cit: 10-12, 52-72 respectively.

[8] The Bone Library (lines 21ff, page 10) in ibid: 10-12.

[9] Jenni Fagan 2021 op.cit: 34

[10] Jenni Fagan (2022: 80) Hex Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd

[11] Jenni Fagan (2012: 1) The Panopticon London, William Heinemann

[12] Ibid: 233

[13] Page 72 Monkey Love Experiment in Fagan op.cit: 71-72

[14] Behind the language of holding here I sense the contests around Winnicot’s definition of ‘holding’ and Bion’s of ‘containing’ as part of their contribution to a wider attachment theory.

[15] Page 9 On The Files in Fagan op.cit: 9

[16] Page 24 9A in ibid: 23f.

[17] Page 1 I’m Not a Fossil, you Are a Curio in ibid: 1-3.

[18] Page 97 The Expectations of Others in ibid: 97

[19] Page 16 Summerhall Almanac in ibid: 14 – 16.

[20] Page 84 Penrose Stairs in ibid: 82 – 84.

[21] Page 27 Fir Tom Leonard in ibid: 27 – 31.

[22] Ibid: 29

[23]Jenni Fagan (2022:31) ‘Fir Tom Leonard’ in ibid: 27 – 31

[24] Jenni Fagan (2022:21) ‘Workshop, Day One’ in ibid: 20f.

[25] Ibid: 21

[26] Ibid: 20

[27] Jenni Fagan (2022: 3) ‘I’m Not a Fossil, You Are a Curio in ibid: 1-3.

[28] Page 38 Who Did Duchamp? in ibid: 36 – 43.

6 thoughts on “‘… how there’s still a kindae / fuckin serious / / as fuck / splendour / / tae every minute ay aw ay this? ’This blog contains my personal views of Jenni Fagan’s (2022) The Bone Library Edinburgh, Polygon.”