‘Inside, the heat of the room pushes down from the ceiling and this is a different kind of bodies on bodies: these one grind and, instead of joy, there is much wanting … We’re all wanting something, though; most of us replacing what we really want with skin, which works until you wake up and the mirror is a blur of time twisting around the throat.’[1] This blog is about a novel that ought to have been shortlisted but was not: Leila Mottley (2022) ‘Night Crawling ’, London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Publishing. Note that it CONTAINS SPOILERS: so do not read if you do not like that: BOOKER REFLECTIONS ON LONGLIST 2022.

In her ‘Author’s Note’ to the Waterstone’s first edition, Mottley refers to the actual case in 2015, which became the germ of her novel, in which several West Coast Police Departments in the USA, including the Oaklands one, ‘had participated in the sexual exploitation of a young woman and attempted to cover it up’.[2] The scent of a ‘true story’ can sell novels but, for a writer of fiction, that which is constructed as a ‘truth’ is especially complex, not least because the roles which cases already contested in courts are often grossly oversimplified. In order to fill out the conceptual roles of villain and victim, a story is told that is confined to the parameters of a crime (or incident of social injustice) as it occurs, is discovered and its effects traced and mitigated within the realms of publicly defined ethical standards. Such standards are rarely uncontested – indeed courts rule on such matters of contested victimhood, guilt and innocence. Newspapers can be particularly bad in that they turn such true stories into a chance for the public to be asked to adjudge such matters for themselves; even after a court has deliberated.

We can see in the photographs below the actual young girl involved in the Oaklands case which is at the base of Mottley’s story. It appears in the story as covered by James Hodge of The Sun in 2017 (a paper not famed for the unbiased nuance of its ethical grasp on social matters). The photographs here feature Jasmine Abuslin as she appeared in court and as she appeared in photography used on her own Facebook page. The latter was used to attract men to paying for sex with her and to pimp her on the streets for use in private parties, including police ones which were enforced returns for the ‘protection’ of street girls. Issues of innocence, guilt, victimhood or collusion with criminal child sex acts speak out from these alone, with issues of the ‘male gaze’ abundant in their construction. Inset is a picture of Brendan O’Brien, the officer who took his own life before allegations of sex with Jasmin at an age under 17 were proven. These events are reflected in the novel with terrifying detail.

We should look at The Sun headline for Hodges’ article which tells of Jasmin’s receipt of compensation from the state authorities for her suffering – in the caption above you can link to the full article. Even in the story headline Jasmin is named as a ‘hooker’, her story encapsulated as that of a ‘mega pay day’. We are very few steps here away from seeing this young girl as a criminal or at best manipulator of the legal system rather than victim of crime. The reasons for receipt of compensation (being to ‘help her heal’) are given in quotation marks not just to indicate the case made by her solicitors but to question the validity of, or even the proof for the case that the concept of someone who is marginalised and degraded socially by being named a ‘hooker’ is worthy of ‘help to heal’. The assumption appears to be that a hooker might be assumed as much as a perpetrator as victim of crime. No wonder then that headline sees her compensation as a ‘mega pay day’ for a prostitute offered crisps as payment previously.

Newspaper headlines assert then the context of contested claims which mark trials of sexual violence. Mottley in cpontrast wants this story not to be about the roles involved in crime, or at least not only that, but to also dig into ‘a world beyond the headline, and for readers to have access to this world’. The role of the main character – the fictional character Kiara replaces Jasmin – is neither victim nor agent of her own fate as Jasmin can still be assumed to be in newspaper headlines above but as someone who has her own voice, as well as responsibility and agency for herself in the story that is the novel rather than the ‘case’ that might be fought in courts: she has ‘the narrative control of a survivor’. In that sense she joins the ranks of the new hero of the postmodern novel of marginal identity:

The stories of black women, and queer and trans folks, are not often represented in the narratives of violence we see protested, written about, and amplified in most movements, but that does not erase their existence.[3]

Let me first state a point that might seem to be obvious. I will take that risk. Survivors are people who live through and on beyond the manifestations of the hurts of oppression (legal, practical, bodily, ideational and emotional) including those offered by systems that ought to mitigate those hurts like the police and health and social care systems for, say, mental health and child protection. But they are also a necessity in a first-person narrative because the voice telling of the events of the story must literally have survived them in order to write of them in ways they, and not others, control. The aim then is to stress control over one’s life to be an agency in at least two levels of control – first over the success of the person navigating life events and encounters by making choices to the maximum of their empowerment in them, and second in telling your own story retrospectively and at the moment or both preferably as you then understand it in your own terms at the salient time and place you inhabit So that’s the obvious point. However, the existent of both kinds of control has political consequences – it ensures that the limits of personal power of those disempowered in any of the social, political, economic and cultural domains touched on in the external world of the story’s action can be addressed at the level of the narrative voice, either as expressions of what is lacking, or desired or as projections of what ought to be made to exist or to happen to redress these limitations. It widens therefore the political agency of the marginalised from victim to agent of a better future world.

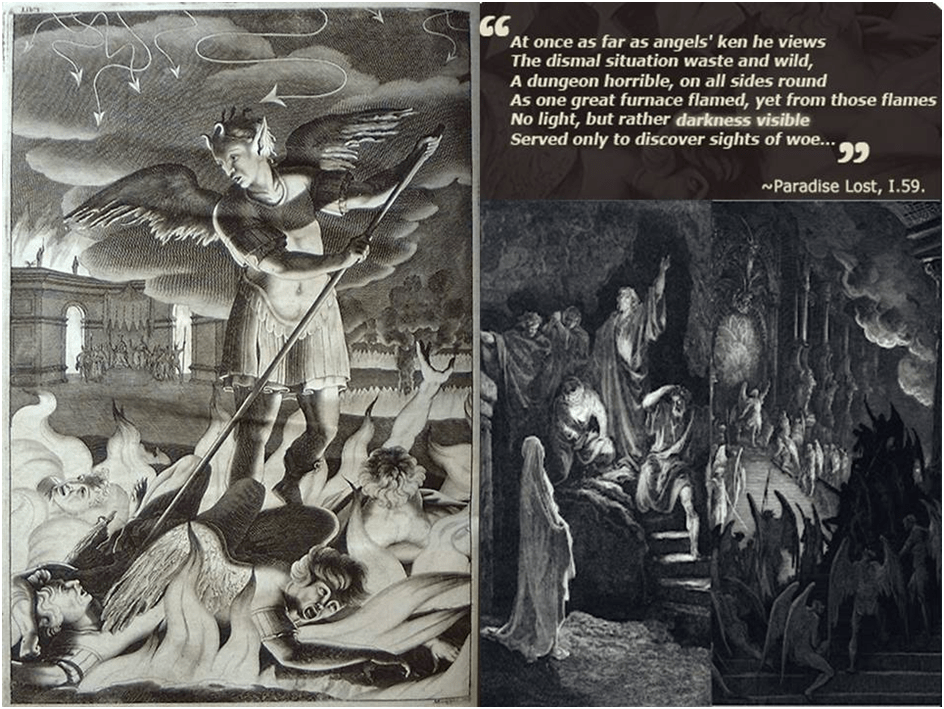

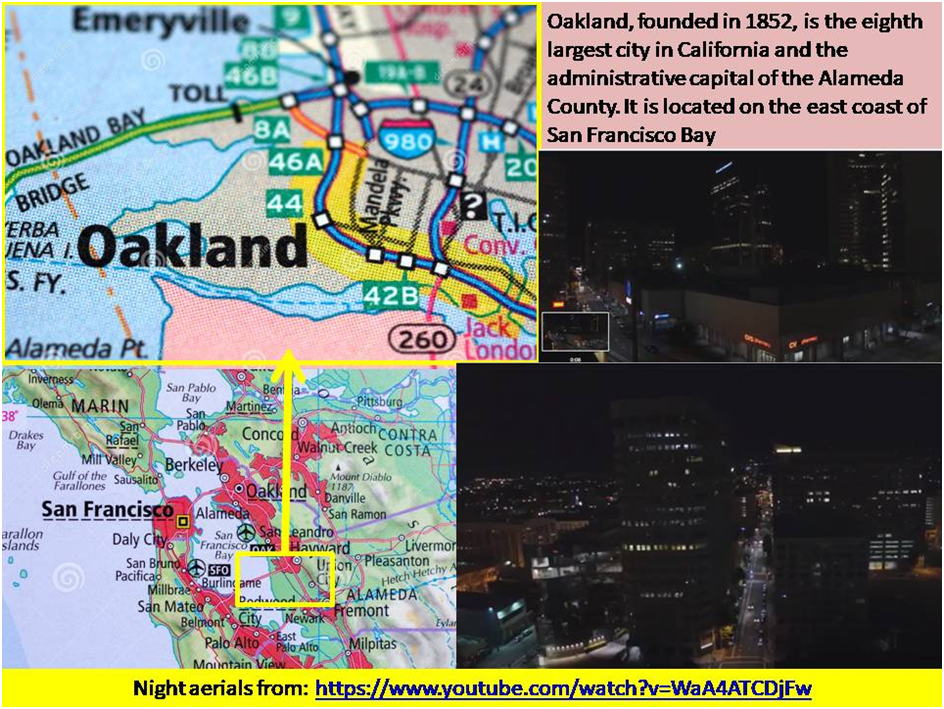

The world of the novel is Oakland, California, rather than the Hell depicted above: a very real world whose daylight appearance of broad streets opens up the satisfaction of any desire that money might buy, if you had it. In the morning however our pockets seem stuffed. But when light fades (even in the middle of the day for this is darkness visible as I’ll repetitively assert) the reality of economic poverty reveals the gaps between the bright streets. It reveals the darkness visible of the city, where one’s own body is subject to the surveillance or violence of the ‘sirens’ that call one to become as themselves in the eyes of men – even policemen. After all, a SIREN can be EITHER the call signal of a police car, which cars or their sound appear frequently in the story, OR the chimera of an unfulfilling desire passing itself off as A FATAL WOMAN).

Let’s take, for instance, this definitive passage, a passage that generates the novel’s title. Kiara is asked by her her girlfriend, Alé, to explain the current state of her life, acting as a prostitute in order to afford the rent to support her and her neighbour’s young boy-child, Trevor:

“Were you gonna tell me?” she asks, …

“I don’t know,” I tell her, and I really don’t.Telling her would Hve been like saying this is my life now, like committing to the streets. Letting the streets have you is like planning your own funeral. I wanted the streetlight brights, the money in the morning, not the back alleys. Not the sirens. But, here we are. Streets always find you in the daylight, when you least expect them to. Night crawling up to me when the sun’s out.[4]

This vision of darkness in the light has the feel of great poetry and one made from, as it were, the language of the streets. The ‘streets’ are not mainly a reference to a great demotic linguistic arena, but they are this too, but of the language of the street of the marginalised in sub-crime, the kind of crime generated by an excess of wealth and poverty simultaneously where the former feeds off the latter for profit, sex and meaning, institutionalising itself in back street sleaze, petty crime and the commodification of all value – and notably the bodies of children, the desire for freedom and the normalisation of relationships mediated through both violence and hard transactions in soft flesh. Mottley dubs it ‘the fear and danger of black womanhood and adultification of black girls’:[5] but sees it as a more general preying on the marginal by the established, effected through rising rents as much as sexual politics, by the brutal reality of the violence of power inequality in action.

The phrase, ‘Night crawling up to me when the sun’s out’, carries a rich set of means associated with that phrase in toto as well as being a great metaphor (like ‘darkness visible’) of the common of everyday life turned into an experience of horror. It’s a phrase associated with white predation on black people, for violence and sex, cars cruising for paid sex opportunities as well as the ordinary inversions in life created by night-time work and pleasure economies. It creeps on you like your skin creeps in fear and danger. This passage associates it with funerals – another kind of night crawling process – and hence with many references of using death to feel life in this novel. It opens with Kiara and Alé visiting funerals of people unknown to feed themselves from the free food, even the funeral symbolically of a dead child – dead before they fully lived, and is encapsulated in the beautiful phrase which, too, creeps on you: ‘touching death and eating lunch’.[6] In this passage, eating is a metaphor for the survivor in a world of death – the ‘closet of death’ in our earlier parable of funereal meats in the novel.[7]

It would spoil too much to be more specific about the metamorphoses involved in our knowledge of Kiara’s mother through the novel’s inner and outer journeys who travels from being a mythic child-murder-figure, a kind of Medea, to redeemer and whose authority preaches against marginalisation as if it were a redemption and an act of transubstantiation – one symbolised by simultaneous survival through eating and evacuating in the name of her daughter:

Cars race by behind her, leave us in the aftermath of their wind, and Mama’s hand is warm.

“Silence starves us, chile. Feed yourself”.[8]

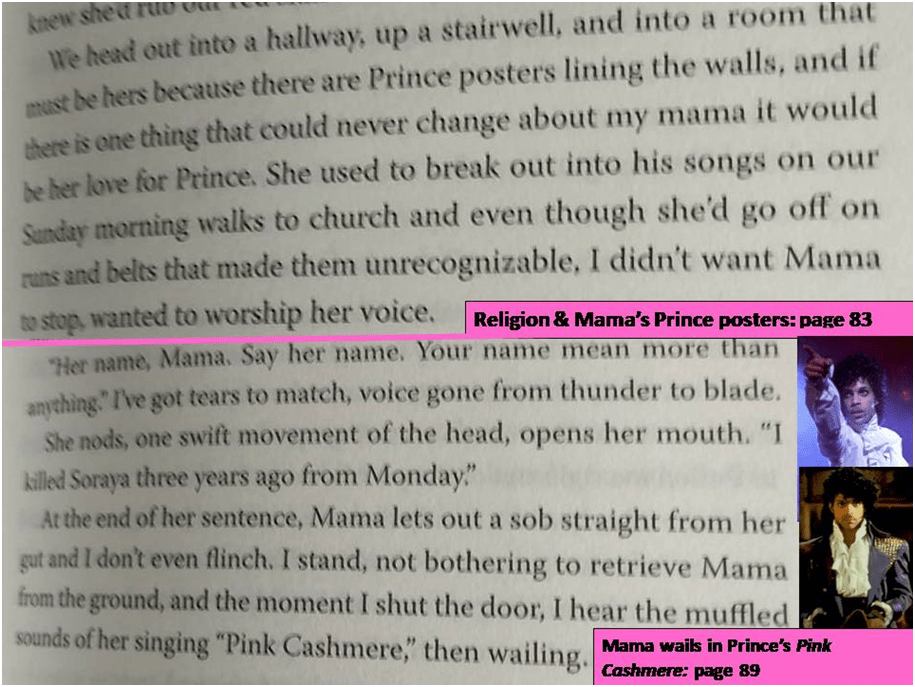

In honour of my best friend, Justin Curley, I have to admit too that we know that Mama will be eventually redeemed because of her love of the singer-songwriter, Prince. At the point I refer to Kiara imagines Mama may be ‘a shape-shifter’ for she ‘don’t look nothing like like’ the woman she knew before, though she is at the moment dressed in Prince memorabilia@ ‘slipping her hands under the sleeves of her old Purple Rain sweatshirt’.[9] But as a luxury and in praise of Justin, let’s look at some of the other passages from the novel in evidence:

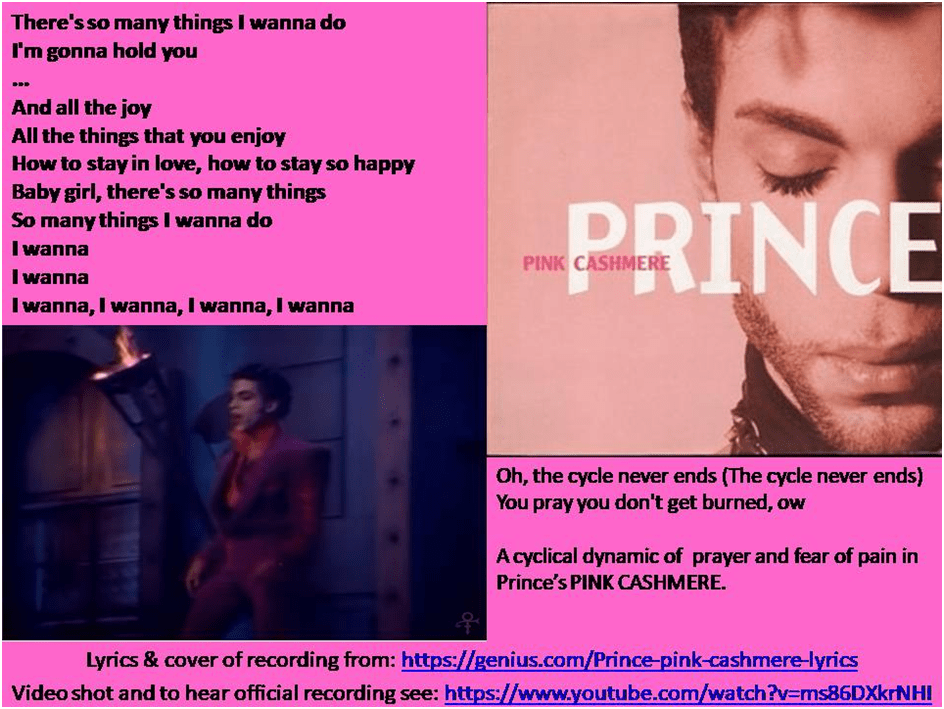

Mama in her prison halfway-house maintains a set of unchanging values that don’t look on the surface to be those of a conventional religion, though no true Prince fan would accept this description I think. The memory Kiara has of Mama is set in religious context – it concerns songs she sang on the way to a ‘church’ on a Sunday; songs transformed by such personalised feature (which Kiara calls ‘rums and belts’) that her voice and the songs are estranged. It is no accident that Kiara wants to ‘worship’ Mamma’s authentic voice.[10] Even as Mama breaks into a ‘confession’, that is more of general sin and culpability we will later learn than individual crime, about her daughter’s, Soraya’s, fate at her hands, Mama sacralises her sorrow thorough a rendition of Pink Cashmere, through which the sorrow of the world wails, as if it were that of Eve herself. The song itself is a song of unlimited wanting that puts even a new love in a cycle of endless and sometimes unspecified (‘Oh, the cycle never ends (The cycle never ends)’) ‘wanting’ or wanting to do for which a pink cashmere coat is a mere and unsatisfactory symbol.

There’s so many things I wanna do

I’m gonna hold you

…And all the joy

All the things that you enjoy

How to stay in love, how to stay so happy

Baby girl, there’s so many things

So many things I wanna do

I wanna

I wanna

I wanna, I wanna, I wanna, I wanna[11]

However, whether or not, I am correct about the role of Prince in Mama’s life of spiritual metamorphosis in the novel, the concern with the complex nature of desire, wanting and the absence of a felt answer to human need is clearly underneath this novel, despite its post-modernity. For instance the section of the novel describing one of the sex parties in the novel is instructive and hence I used it in my title for this blog:

Inside, the heat of the room pushes down from the ceiling and this is a different kind of bodies on bodies: these one grind and, instead of joy, there is much wanting … We’re all wanting something, though; most of us replacing what we really want with skin, which works until you wake up and the mirror is a blur of time twisting around the throat.[12]

As a picture of debauched sex in process, it is less than an attempt to appeal to the possible pleasures of that activity. Its feel is of oppression – of the literal weight of the descending ceiling and the absence of pleasure in the plethora of felt ‘wanting’ (like the ‘wannas’, above, in Pink Cashmere). What we want is ‘skin’ but what does that surface and container mean to us. It is, in this novel, and in life, sometimes a bearer of colour markers that differentiate people in terms of social and economic power and access to services in racist societies, but it is also the receptor of touching and feeling, sensations that segue into emotion, and of some import in this novel. In a key motion, for instance, Kiara’s hands are touched by Alé, a lover who also ‘reads’ the skin of palms, in examination of the cuts Kiara inflicts on herself to register the pain of unwanted and premature sexualisation or ‘adultification’:

All the lines in my palm d Alé used to read are cut; some of them bleeding, some of the scabbing, some of them too deep to decide how to heal. I’ve been clawing at them, after I finished gnawing on my nails.[13]

This painful self-harming parody of the effects of being made the object of desire (or one’s skin at the least being made so) is also a self-consumption, self-eating, which Alé attempts to turn into an act of mutual social love at a chosen family table. Here the two girls and their chosen son, Trevor, for it is eating that brings them together in communion. For though they “never in the same place at the same time”, that doesn’t apply “when eating”.[14]

Social problem formulations in the English nineteenth century have often focused on supposedly Darwinian paradigms in which the poor realise the strength of the adage ‘Eat or be eaten’ (discussed in an excellent online article by Matthew Barad), or in Dickens’ terms, in Our Mutual Friend, ‘scrunch or be scrunched’. The paradigm has been reinvested into theories of ‘moral capitalism’ (an oxymoron if there ever was one) by neoliberals and social Darwinists as Barad shows, and it makes an appearance I believe in Night Crawling, for this is a novel where those who cannot eat, get consumed by others, or by some sense of consuming fate, or (as we have seen) themselves. The party at which Kiara’s fate is decided, shows sexual wanting (‘ravening wanting’) for the youth of black girl prostitutes by rich, old and powerful as a complex of the swallowed, swallowing and regurgitated: ‘The eyes are a ravenous wanting now, like the night has swallowed them and spit out only desire’.[15] It is only late in the novel that we learn that the beautiful, but now aging Camila has had her desire to merely ‘live in her body however she damned well pleased, twist her hips, and strut around in neon’, as a self-assured transsexual woman. Camila’s joy in being externally the woman she feels she is inside is consumed by male fantasies that do not feed her as she is but as these men want her to be, meanwhile eating out financially on the earnings of her body:

“My speciality was answering to ‘Man Looking to Dominate Young Tranny’. All them fuckers was nasty, but I was young and I was happy someone wanted to fuck me and pay for my rent at the same time. Ended up getting all the shit I wanted from that money, got my face done, paid for hormones. Eventually got hired as an escort at a real agency, but they took a good cut of my money and I wasn’t even getting any good gigs”.[16]

Exploited or scrunched. Thinly fed so that she survives but mostly at the cost of being eaten away by the agency of the desire of exploiters – literally ‘eaten’ alive and trapped in that role, providing fresh meat for male desire from a pool of children.

The dominant metaphor for being consumed is drowning, or being swallowed by a sea or ocean of water. It is not just because of the common enough metaphor of economic provision as a means to ‘keep us afloat’.[17] Surviving such swallowing is learning how to swim underwater with joy – and this parable of learning to swim accompanies metaphors through the novel too and applied to Kiara’s drowned sister, Soraya, Trevor – swimming in the ‘shit pool’ created by and for his mother, Dee (Dee’s ex-boyfriend throw bags of collected dog faeces into their communal flats’ swimming pool). Trevor teaches Kiara to swim, although Kiara panics at first, she learns to ‘feel like she’s flying’ before she ‘dives back under’.[18]

The novel ends with Kiara, now having learned to swim by Trevor, diving into the ‘shit pool’ with Trevor: ‘Trevor and I finding our laughter just like Dee somewhere in the beyond, … letting the water swallow us’.[19] This final sensation of being swallowed is a kind of acceptance of survival and saving joy. The novel had opened with Trevor swimming alone in that pool where Kiara says that the ‘idea of drowning doesn’t bother me. Though, since we’re made of water anyway. It’s a kind of like your body overflowing itself’.[20] Yet the first sex she has with an adult man shows that drowning in your own body, under the hands of oppressive elder white men, contains fear – as the red cherry drink they ply her with feels as if, with his penis, is ‘still filling me up, still drowning me in it’.[21] These metaphors and parable-like stories are those of a poet with language using new resources from neglected communities and their cultures. Crawling is a swimming motion too and we learn to swim in the language of this novel because of the excellence of this poetry and its music, as it combines stages of life from birth, childhood to the life of unsatisfied ‘live ghosts’ from which Kiara is reborn. The poetry is not immediate in yielding meaning because we have to grow from how it perceives the eternal repetitions beneath modernity. Take this example, which hints at a watery sinking too, of her street journey with her mother:

I think this is the closest thing to being a live ghost. Disappearing into the roadside trash and trees that somehow figure out how to grow in California’s eternal drought. Existing as the most salient and invisible thing on the road, both sinking into the dark and so terribly misplaced.[22]

Hence, I do not want to end this blog by suggesting that this novel answers all the questions it raises – even the more clearly mundane politics of the issues black women with white feminism for its denial of the reality of racism directed at black men. Here is a feminist novel which refuses to relinquish care and support for men against racism amongst its demands. Male children still need female love, even siblings. As Kiara says to Dee (the mother of Trevor) of her own Mama:

I need an answer, need Mama to patch together the pieces of these lives we’ve made for ourselves, give me a reason that would make her feel like mine again, like someone I might know. I need her to tell me mamas can change, that there is hope for Trevor, for Marcus, for me.[23]

I wonder how white feminism reads this strong placement of continuing responsibility on the black mother for men as well as daughters? I wonder if I have truly got it. What is clear that female roles like ‘holding’ that were once stressed by men hated inside white feminism, like D.W. Winnicott, are valorised here in Kiara’s responsibilities for her brother and to mitigate Dee’s bad mothering for Trevor. If white social workers persuade the young Kiara that: ‘This apartment doesn’t know how to hold a child like Trevor. I don’t know how to hold a child like Trevor’, it is she who, when Trevor collapses – physically and psychologically beaten and ‘back in the fetal position’ – learns to lift him up ‘like you carry a small child to bed after they fall asleep on the bus’.[24] Kit Fan in a review in The Guardian has said wisely in ways that are more with meanings that are followed through by them or could be by me. I want to cite her words though:

When asked how to write in a world dominated by a white culture, Toni Morrison once responded: “By trying to alter language, simply to free it up, not to repress or confine it … Tease it. Blast its racist straitjacket.” At a time when structural imbalances of capital, health, gender and race deepen divides, the young American Leila Mottley’s debut novel is a searing testament to the liberated spirit and explosive ingenuity of such storytelling.[25]

Do read this wonderful novel. Why, oh why, was it not Booker shortlisted? It’s a sin.

All the best

Steve

[1]Leila Motley (2022: 121f.) ‘Night Crawling ’, London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Publishing

[2] Ibid; 271

[3] Ibid: 272

[4] Ibid: 105

[5] Ibid: 272

[6] Ibid: 14

[7] Ibid: 15

[8] Ibid: 239

[9] Ibid: 232

[10] Ibid: 83

[11] Lyrics from: https://genius.com/Prince-pink-cashmere-lyrics

[12] Mottley op.cit: 121f.

[13] Ibid: 159

[14] Ibid: 160

[15] Ibid: 129

[16] Ibid: 230f.

[17] Ibid: 64

[18] Ibid; 138

[19] Ibid: 269

[20] Ibid: 1

[21] ibId: 41

[22] Ibid: 237f.

[23] Ibid:233

[24] Ibid respectiveyl: 226 & 246

[25] Kit Fan (2022) ‘Nightcrawling by Leila Mottley review – a dazzling debut’ in The Guardian (Thu 2 Jun 2022 11.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jun/02/nightcrawling-by-leila-mottley-review-a-dazzling-debut

One thought on “‘Inside, the heat of the room pushes down from the ceiling and this is a different kind of bodies on bodies: these one grind and, instead of joy, there is much wanting … We’re all wanting something, though; most of us replacing what we really want with skin, which works until you wake up and the mirror is a blur of time twisting around the throat.’ This blog is about a novel that ought to have been shortlisted but was not: Leila Mottley (2022) ‘Night Crawling.’ BOOKER REFLECTIONS ON LONGLIST 2022.”