‘She had written a secret book, … a book about a young man called Julian who was in hiding, disguised as a girl called Julienne, in a similar place. … And how did the story progress, asked the Djinn,.., how did you resolve it? I could not, said Dr Perholt. It seemed silly, in writing, I could see it was silly. … the more realism I tried to insert into what was really a cry of desire – for nothing specific – the more silly my story.’[1] This blog is about Three Thousand Years of Longing, the 2022 film directed by George Miller, starring Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba. Miller wrote the screenplay with Augusta Gore, a 1994 short story. It also uses the text of that story by A.S. Byatt, “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” in A. S. Byatt (1994) “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye: Five Fairy Stories”, London, Chatto & Windus.

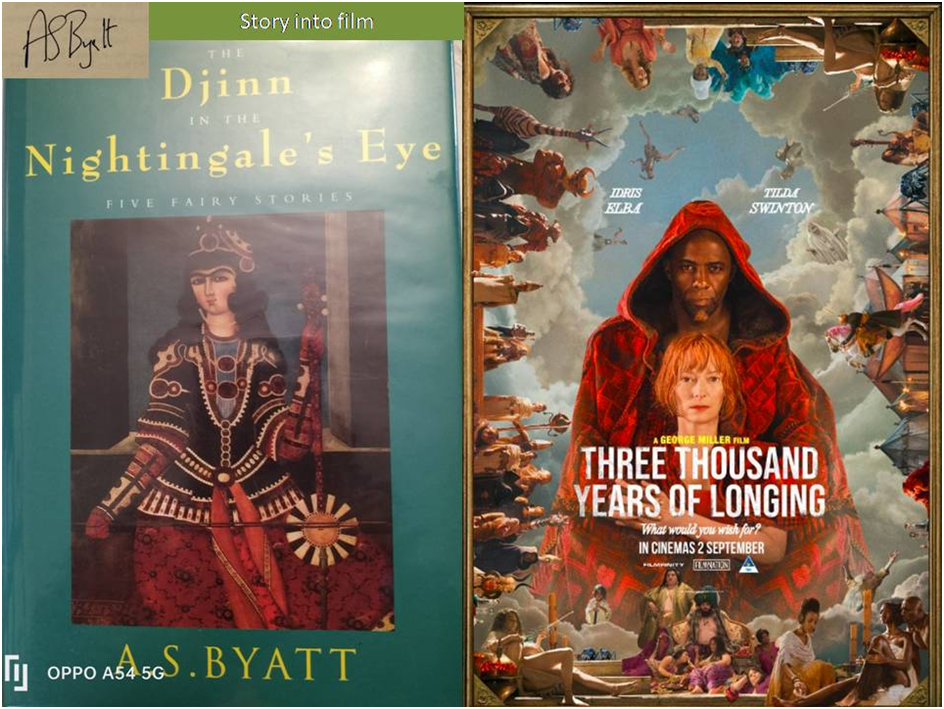

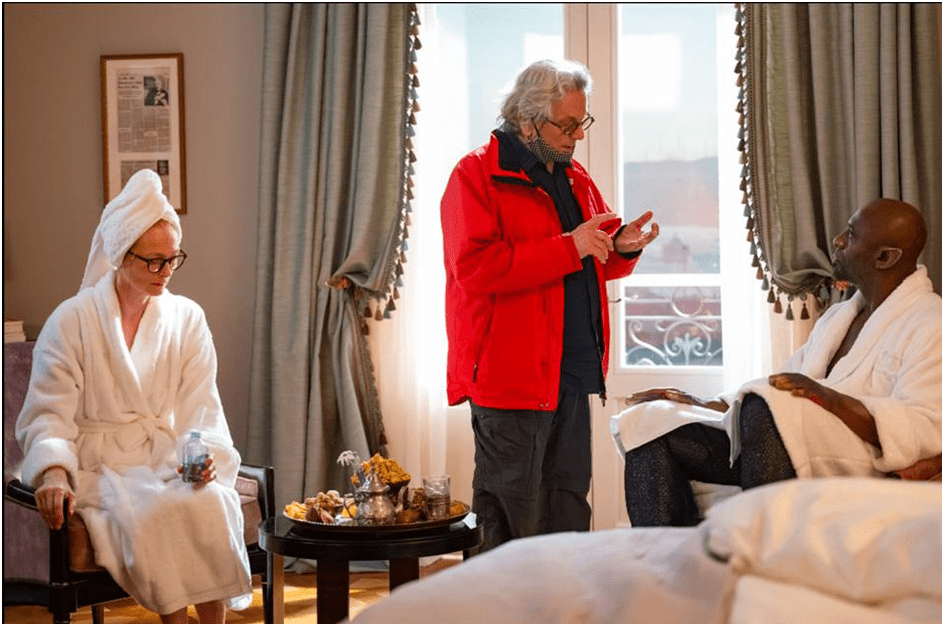

The original story, published in 1994, The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye, on which the 2022 film Three Thousand Years of Longing is based, and that film itself, focuses on the life of a narratologist: Gillian Perholt by name in the story, but Alithea Binnie in the film. Narratology, simply defined, is the academic study of stories and the rationale of their means of delivery. There is less demonstration of the narratologist’s work in the film than the story: the latter indeed includes almost all of a lecture, delivered at a conference on Stories of Women’s Lives (the focus on women’s lives is not that of the conference in the film) in Istanbul (the main setting of the key events of film and short story). It is a lecture on the ‘Clerk’s Tale’ from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, the story of ‘Patient Griselda’, in which Dr Perholt tells that story in her own way. It includes many excursions into other stories of women’s lives, including her interpretation of ‘a lull in the narrative’, which she compares to the lull in the told life of Hermione the Queen in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale with the smart generalisation that, for these fables; ‘A woman’s life runs from wedding to childbirth to nothing in a twinkling of an eye’.[2]

The focus on women’s lives as a primary theme is insistent in the long ‘short story’, though to my mind more peripheral, if decidedly present, in the film. ‘Patience,’ in the story of Griselda, is not only an attitude to waiting on events governed by others, usually the authority of males, but the very definition of Christian and Old Testament virtue (that shown by Job) and is beautifully conveyed in a rich summary of it by Byatt. The summary combines the grace of a simple but patriarchal religion, together with a more sophisticated and nuanced, but therefore the more oppressive, glance at the mores which equate female fertility with the hidden. This is oppressive but it is also with something that has become through time the undoubted ‘possession’ of the woman who bears it, even as suffering and subjection, and therfore far from being just a sign of subjection:

Naked, Griselda tells her husband, she came from her father, and naked she will return. But since he has taken all her old clothes she asks him for a smock to cover her nakedness, since “…. In exchange for my maidenhead which I brought with me and cannot take away, give me a smock.[3]

The serious attention to women’s lives, and the reduction of femininity to the material ‘object’ of sexual pleasure, on the one hand, and the reproduction of patriarchy on the other, is there in much more shadowy ways in George Miller’s films. Many women’s lives are implicated in Byatt’s story, which are excised from Miller’s. Byatt’s 1994 short story is more concerned with a lament for the lost energies of female active work and their lost subjective perspective in public life. About Miller’s version of the story I will write later but it is worth noting now that if in the original story there are three thousand years of longing, this duration of desire for the absent is not that of the Djinn’s triple incarcerations, as is the case in Miller indubitably, but of the women who necessitated these incarcerations – each in their own way lost in stories of romantic and sexual love, the accident of their fertility and perhaps, as importantly, loss to larger purposes in art, politics and the serious business of life. Such women have, besides a keenly observed independence bought by morality, like Griselda, nothing to trade upon but what their naked being means to the male gaze and male desire (often merely possession) and men’s active appropriating hands.

Byatt’s women, in this story, are not all from the represented lives and tribulations of literary creations, like Griselda or Milton’s Eve, although to these kinds of representation too we must return. They also include women represented in the modern news media with other kinds of struggle than those imagined for them by patriarchal tradition. They include the lives of ‘four generations of women’ seen on the television (which medium of transmission so puzzles and troubles the Djinn); women who are, Gillian asserts, ‘beautiful people still’ (like their historic and mythic forebears including the Queen of Sheba who appears large in the Djinn’s life-story, in the film and short story). Gillian tells the Djinn of an old Ethiopian woman amongst those three generations of women seen on her TV, ‘framed in her own limbs’ by virtue of the camera operative’s skill with a lens (and appearing to speak therefore out of an ‘enclosure made by her own body’). This is one of many women trapped or enclosed in their bodies. They are trapped because women’s bodies are over-interpreted in patriarchal traditions as vessels of continuing patriarchal governance and reminders of the necessity of such continuance. Nevertheless, they are imprisoned in this vessel made of an ideological framing of the body just as securely as a Djinn can be in a ‘nightingale’s eye’ (or in transliterated Ottoman Turkish a c̗̗esm-i bülbül). This is what the old woman, thus framed, means when she says that: “It is because I am a woman, I cannot go out and do something.[4]

Women throughout the long short-story are contained by male desires and male ‘rights’ of governance over objects and persons, but most of all, of an idea of women conceived of as objects, of which the story of Griselda is merely a fictive exemplum. However, it is not the only example of stories, in which a ‘stopper’, like the one closing any filled vessel or container, is used to stop something escaping, or if all else fails, killing it with a strangling cord. Since a Djinn cannot die, containment, rather than death, is the first option that is taken, but this option has been used to end-stop women throughout history and representations thereof, though this time the enclosed energy is that of frustrated and under-used femininity. Our ‘own response’ to Griselda’s story is ‘outrage’:

… at what was taken from her, the best part of her life – at the energy stopped off. For the stories of women’s lives in fiction are the stories of stopped energies – the stories of Fanny Price, Lucy Snowe, even Gwendolen Harleth, are the stories of Griselda, and all come to that moment of strangling, willed oblivion.[5]

These women are unlike the mythical Queen of Sheba, met in the Djinn’s story of his first incarceration, who refused to ‘submit to the prison-house of marriage’ and other ‘invisible chains which bind me to the bed of a man. However, even , the current British Queen, Elizabeth II, ‘has no power. She is a representative figure’.[6] She is representative not only of a nation but of relative female powerlessness in the public realm in which things are decided and executed. The Djinn’s stories over three thousand years, after the imaginative Amazonian triumph imagined of Sheba, are stories like that of the Turkish woman, Zefir: ‘a great artist’ but one characterised by the fact that ‘no-one saw her art’: The Djinn says, ‘She told me she was eaten up with unused power’.[7] Asked to tell her own story, Gillian Perholt panics because it ‘seemed to her that she had no story, none that would interest this hot person with his searching look and his restless intelligence’ that was not merely a product of vast changes in the cultural and technological, and to some extent, social superstructures of the world of Western capitalism. Such an end-stopped story could not be understood she muses without him knowing ‘the history of the western world since Zefir has mistakenly wished him forgotten …’.[8]

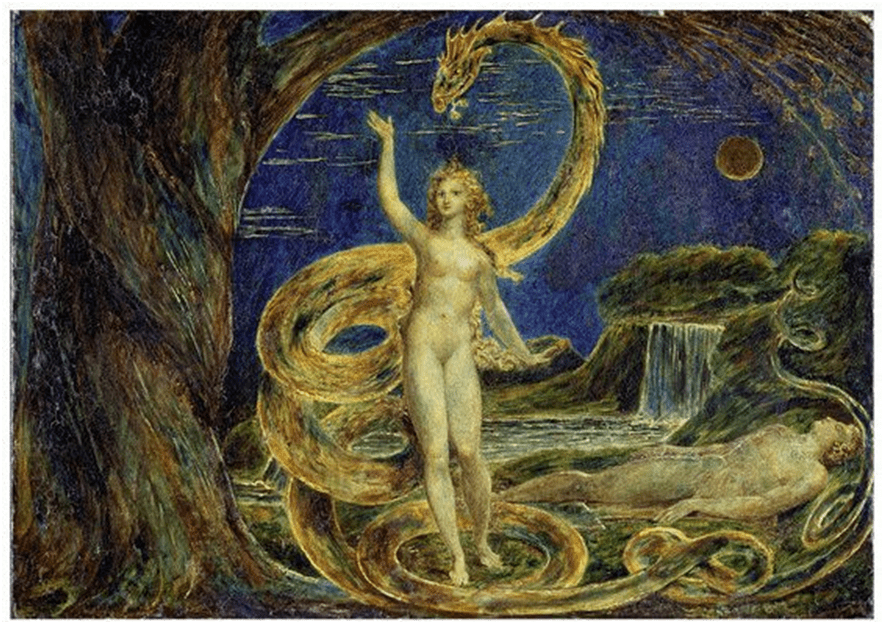

The archetype of frustrated powerless woman is the mother of all in Judaeo-Christian and Islamic traditions, Eve. In Milton’s powerful version of her story, she, punished for attempting to seek power and knowledge in her own person rather than through her husband, from whom she is imagined in that tradition to be born. It is she who is associated with the crowning phrase of the story for the illusion of power in women (‘floating redundant’), and one that will characterise women in both the aspirant and decorative roles in which they only look like they are powerful, or who represent power lying elsewhere – in men. Even the Djinn, Gillian notes is in ‘no hurry for’ Zefir ‘to escape – to exercise her new powers somewhere else’, once he has given her the beginning of a knowledge of Aristotle and Euclid and much else – making them like a perfume essence imprisoned in bottles (brilliantly symbolised in the film). The Djinn advises Zefir to stop where she is, as the wife of a rich merchant and under the Djinn’s tutelage, using knowledge as a superficial enhancement of her life, whilst he rather enjoys being a teacher who never stops teaching pupils whom are ready to be let go (and grow), knowing he ‘loved my own power to change her frowns to smiles … to enjoy her own body, without all the gestures of submission’ but at the same time ensuring her submission is real. The relationship is that too between Milton’s Adam and Eve, and on the next patriarchal level, God and Adam.

The phrase ‘floating redundant’ comes, of course from Paradise Lost Book IX and is quoted near the very beginning of the story in its original context(since the words are neologisms invented by Milton), which needs the same lengthy reproduction to capture the associations with aspirant flight in the air and swimming in fluids or flood that will be recalled later and throughout the story:

… Not with Indented wave,

Prone on the ground, as since, but on his rear,

Circular base of rising folds, that towered

Fold above fold, a surging maze! his head

Crested aloft, and carbuncle his eyes;

With burnished neck of verdant gold, erect

Amidst his circling spires, that on the grass

Floated redundant: pleasing was his shape,

And lovely;[9]

Perholt in the Byatt story plays with the etymologies of both words in the phrase ‘Floating redundant’, which are both derived from notions of watery excess but from different linguistic traditions. She claims though to add more modern meanings, such as that of being ‘superfluous to work requirements’ in the language of employers or of being past the age of conventional usefulness in the conventional roles of wife and mother that define Western womanhood: she even sees herself as ‘redundant as a woman’.[10] Even as a narratologist (for which role she was ‘no means redundant’) Perholt is something of an ironic object of reverence, unlike the sybils or even the crones she references. Doubts about the value of her life task resurface through the story continually, sometimes in the form of punishing delusions, sometimes in bathetic hyperbole – after all what ‘her life and field of power’ amount to is that of someone with ‘a store of money’:

… who flew, who slept in luxurious sheets around the world, who gazed out at the white fields under the sun by day and the brightly turning stars by night as she floated redundant.

It is a fairly damning indictment of a life not in any ‘real’ terms useful, of an enforced and leisurely drifting on the tide and waves of a life of little significance in the world. It should remind us of the sentence in the opening of the story that says (ibid: 95) that she ‘was a woman who was largely irrelevant, and therefore happy’ (my italics). In her hallucinations she becomes Lot’s wife transformed into ‘a pillar of salt’ – like an enclosed genie, ‘her voice echoed in a glass box, a sad piping like a lost grasshopper in winter’: no more than an empty female form ‘with a veiled head bowed above emptiness and long-sinewed arms, hanging loosely around emptiness …, a thing banal in its conventional awfulness’. That emptiness metamorphoses again to be ‘a windy hole’, a monstrous she-figure’s ‘belly and womb’. In short being a narratologist returns Perholt to a vision of woman unfulfilled except as a mechanism for fertility and reproduction, and gives no enduring purpose, such as that to which some men believe, they, via the social permissions granted through patriarchy, have access. That power really does men no good either is another issue in this story.

We see the floating redundancy again in the imagination of Gillian in flight across oceans in aeroplanes and in swimming in pools (all caught up in fluid waving motion) that are in fact constrained but yet give the same sense of opulence and temporary power to her as seeing the serpent does to Eve in Paradise Lost. See of all these passages echoing that Miltonic moment, one in which the watery motion of the serpent of Book IX is lent to convey Gillian’s joy in swimming in a shadowy underground pool that, however ‘satisfactory’ it may be, is also decidedly ‘small’, as women’s compensatory expenditures of energy are. They make their ‘waves’ but only ‘little’ ones:

… she extended her sad body along the green rolls of swaying liquid and felt it vanish, felt her blood and nerves become pure energy, moved forward with a ripple like a swimming serpent. Little waves of her own making lapped her chin in this secret cistern. … The nerves unknotted, the heart and lungs settled and pumped, the body was alive and joyful.

Gillian sees this Miltonic serpent too in the Djinn’s emergence from the bottle known as the nightingale’s eye, whose largess contained in a small room, is ‘curled round on himself like a snake’.[11] The Djinn’s final story moves Alithea to the point where she wishes for Djinn and herself to fall in love. Her attention soon however moves from this strange man – who nevertheless displays himself in the power of control of being ‘swelled and () diminished’. The phallic play here is more on the surface than in Milton, its source, even down to the ‘strong horripilant male smell’ associated with the real organ. When the Djinn shrinks and ‘tucks away’ the ‘mound of his private parts’ that temporarily masks him, the narrator and Gillian (for whose consciousness is here but that of a shared female perception of men much more rarely shared with men) think: ‘It was almost a form of boasting’. This is a kind of humour less present in the film too I think. That snake returns much tamed and contained (both ‘small’ in size and locked in a glass paper weight) at the very end of the story but still ‘curled on a watery surface’.[12]

The account I give above gives some idea of the complexity and nuance Byatt gives to the examination of female lives, which is one that examines not only the objective lack of power of women in an oppressive historical paradigm that we usually name patriarchal but also its subjective forms – including the supposed mitigation of being expert in feeling, caring and other forms of empathetic identification. And it would be wrong, as my dearest friend, Justin Curley, explained to me when he saw the film with me and my husband. He argued that an examination of the constriction, marginalisation and disempowerment of women’s lives is merely assumed in the film, rather than explained – in other contexts than merely the story of meeting the Djinn. He felt that it might be forgivable in 2022 to make those assumptions about an argument that is, in most respects (at least in discursive forms) won: the reality of women’s lives is better understood even if the politics of change required to make it happen still remains undelivered.

These circumstance would, he explained to me (of course I may have misunderstood), justify the concentration in the film on the isolation of the divorced Alithea (whose initials on her suitcase (A.B.) observed in the film, he believes to be a bow to the original author (Antonia Byatt)). For in the 2020s women’s alienation and marginalisation is less problematic since the removal of children and pregnancy from their lives removes from the equation in one way or another, he believes, men who refuse change, supported in that still by the patriarchal structures that support them. For women the answer is not a husband nor children nor vows of enduring love but mature friendships in which their tendency to mutability has to be accepted. To test this we discussed a feature shared between both film and short story and part of the narrative told to the Djinn by Alithea and Gillian respectively. That feature in the story I cite in my title and had believed it absent from the film until Justin reminded me it was not. The version in the story reads thus:

I am a naturally solitary creature, the Doctor told the djinn. She had written a secret book, … a book about a young man called Julian who was in hiding, disguised as a girl called Julienne, in a similar place. … Was she a lover of women in those days? No, said Dr Perholt, she believed she had written the story out of an emptiness, a need to imagine a boy, a man, the Other. And how did the story progress, asked the djinn, and could you find a real boy or man, how did you resolve it? I could not, said Dr Perholt. It seemed silly, in writing, I could see it was silly. I filled it with details, realistic details, his underwear, his problem with gymnastics, and the more realism I tried to insert into what was really a cry of desire – for nothing specific – the more silly my story.’[13]

Having read that out to Justin and not finding it in the Wikipedia synopsis of the plot of the film, I had forgotten that a version existed in the film too of this same sub-story. In it Alithea (Anthony Lane in The New Yorker says her name ids a distortion of the Greek word for truth: ‘a quiet joke, given the tallness of the tales that she prefers’ [14]) imagines a figure who appears in the film in a monochrome cartoon format. Gone is anything to do with desire or the genderqueer of any form, which might be in Byatt’s text, in favour of a story, as Justin put it of ‘just an imaginary friend’. A sketch of a boy in the film flashback representing Alithea’s story hugs and comforts the lonely child (played by Aylala Browne), sitting pressed to a wall and representing Alithea as a young girl. The phrase ‘just an imaginary friend’ feels precise to me, for Byatt brings to her version the same preoccupation with the emptiness that will be associated later with the roles left for adult women to inhabit, and which mat haunt even their adult lives however socially prestigious or validated by institutional education.

The film has usually reviewed in a way that highlights its limitations. The New Yorker finds that this:

… lovely and lolling work is dulled by unworldliness. Far too much attention is lavished on the never-never lands of Eastern reverie, and when we are spirited to modern realms, toward the end, implausibility reigns; no lecturer would dwell in a house as grand as Alithea’s London residence, and her elderly xenophobic neighbors are a distracting cartoon.[15]

Thus speaks, I think, someone with little grasp of the marriage of the English class system with educational opportunity and job-role opportunities or English xenophobia, though the latter is undeniably dealt with in a comic manner. That too is an Enlists trait I believe. Peter Bradshaw, in The Guardian, who does understand the oddness of English social life still finds the film a ‘garrulous yet almost static movie’ with ‘no single important storyline’.[16] Christina Newland in The i also sees a mix of ‘open-hearted fantasy’ together with the ‘perceived silliness of the story’ that ‘will not be for everyone’.[17] In my opinion, these views fail to comprehend that this work is not about narrative just because it is about a narratologist, and that it rather takes on board the same interest as Byatt has in what we could almost call philosophical dialogue, where stories play the role of analogies for states of being, as in Plato’s philosophical work perhaps, if rather more entertaining and telling more modern jokes. Indeed Miller goes somewhat further in that direction. Where Byatt has the bemused djinn lift from the television in Gillian’s Turkish hotel bedroom an homunculus representing Boris Becker (then merely a tennis player), Idris Elba’s djinn to Alithea’s shock (as played by Tilda Swinton) lifts out a homunculus of Albert Einstein. The play with ‘the swell and contraction of physical forms’ as Anthony Lane says, may have less to do with the play on the power, gender and the sexual in Byatt, as I have tried to show above, than with Miller’s interest in relativity as a necessity of filmic visual representation. As Lane also says:

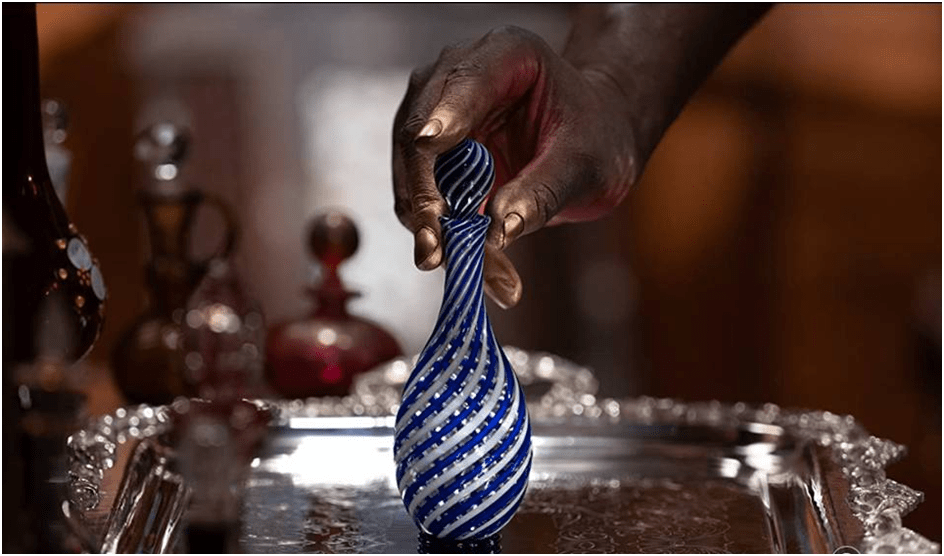

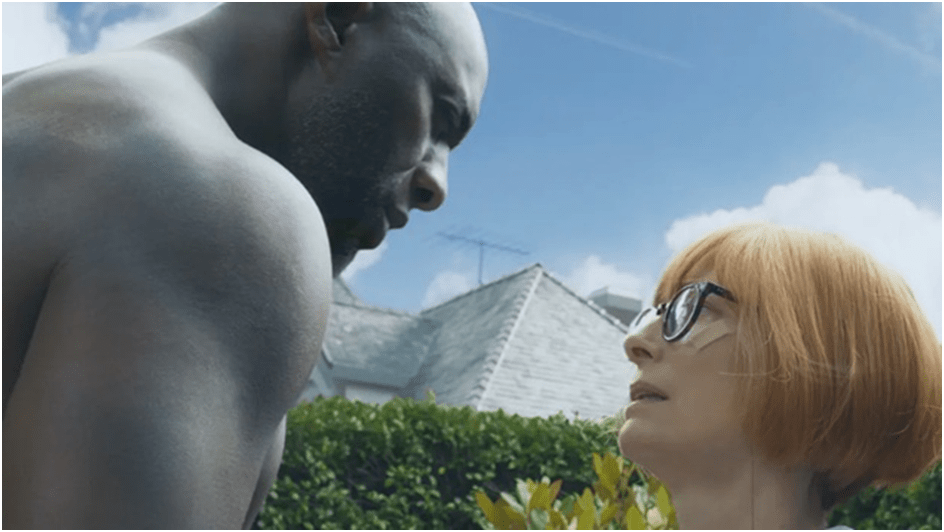

Miller has always been drawn to elasticity. The main baddie in “Mad Max: Fury Road” was a humongously toadish brute, and, as “The Witches of Eastwick” (1987) reached its climax, Jack Nicholson turned into an ogre, his gargantuan features framed in a kitchen window, and then into the merest mini-head, which popped like a bubble into nothingness. In short, we should not be taken aback by the Djinn as he erupts from his flask into Alithea’s suite. His hand alone is enough to fill a room, and my favorite (sic.) shot shows his wandering finger, as big as a canoe, brushing against the keyboard of a laptop, which, with a soft pdoing, powers up.[18]

Film and story are different art forms and we should not expect a film to replicate the effects, even of meaning, of a book, and therefore Lane is useful here in helping us to do this. However, we perhaps also should not expect genre categories to determine what is good, bad or indifferent in any film or story, for the best of both bust genre containers open and release something new. What unites the two versions is I think an interest in the imagination of what modernity does to notions of space and time, both in the availability of air travel for all (and not just supernatural or imagined beings) or the conveyance of messages in fragments of data whether in radio or audio waves or the digital. In the film Idris Elba is confused by messages in the air waves (and a receiver aerial appears in the background of one conversation in an English garden).

Later on, as the Djinn sickens near the end of the film, his being fragments into bits that float redundantly in the air of Alithea’s cellar and home. This takes up a wonderful passage in the novel but renders it visible and an element of the film’s denouement. The djinn is pondering about television and how it works to enclose ‘very beautiful’ men. His speech recalls Caliban’s famous monologue in The Tempest:

The atmosphere here is full of presences I do not understand – it is all bustling and crowded with – I cannot find a word for it in my language or your own, that is, your second tongue, – electric emanations of living beings, (…), like motes in the invisible air – something terrible has been done to my space – to exterior space since my incarceration – I have trouble in holding this exterior body together, for all the currents of power are so picked at and intruded upon …[19]

This is writing of a high order and maybe George Miller’s film work dealing with Elba’s sickening djinn is also of a high if very different order, with more varied meaning. What is clear is that we miss the point of myth and fable if we see it as dated, for perhaps scientific thought can only be imagined through similar myths. How, for instance, can we conceptualise the meaning of how ‘men and women hurtled through the air on metal wings’: for this is part of a passage that opens Byatt’s story is used too in the opening of Miller’s film, alongside TV images which ought to be equivalent to the meaning of the words but aren’t – in this case of a huge Boeing aeroplane flying in the air.

All the best

Steve

[1]A. S. Byatt (1994: 232f.) ‘The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye’in The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye: Five Fairy Stories London, Chatto & Windus, 93 – 277.

[2] A. S. Byatt (1994: 114) ‘The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye’in The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye: Five Fairy Stories London, Chatto & Windus, 93 – 277.

[3] Ibid: 115. The first sentence cited is a variation of Job Ch 1, verse 21. See https://biblehub.com/job/1-21.htm Her substitution of ‘my father’ for Job’s ‘mother’s womb’ probably emphasises the variation of the meanings of patriarchy for women and is a characteristic Byatt subtlety.

[4]For c̗̗esm-i bülbül see Ibid; 183. The term is also used in film in the scene set in the Istanbul souk where the bottle thus named is bought

[5] Ibid: 121

[6] Ibid: 208

[7] Ibid; 224

[8] Ibid: 231

[9] Milton Paradise Lost Book IX lines 496ff. (see http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Milton/pl9.html) as cited Byatt op.cit: 99f.

[10] Ibid: 101 – 103

[11] Ibid: 192

[12] Ibid; 275

[13]ibid: 232f.

[14] Anthony Lane (2022) “Three Thousand Years of Longing” and the Perils of Unworldliness” in The New Yorker (online) (August 9 2022) available in: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/09/05/three-thousand-years-of-longing-and-the-perils-of-unworldliness

[15] Ibid.

[16] Peter Bradshaw (2022: 12) ‘Gentle genie has a lot of bottle’ in The Guardian (Friday 2 September 2022).

[17] Christina Newland (2022: 43) ‘Fantastic marvel of storytelling brio’ in The i (Friday 2 September 2022).

[18] Anthony Lane op.cit.

[19] A.S. Byatt op.cit: 196f.

One thought on “‘She had written a secret book, … a book about a young man called Julian who was in hiding, disguised as a girl called Julienne, in a similar place. … And how did the story progress, asked the Djinn,.., how did you resolve it? I could not, said Dr Perholt. It seemed silly, in writing, I could see it was silly. … the more realism I tried to insert into what was really a cry of desire – for nothing specific – the more silly my story.’ This blog is about ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’, the 2022 film. It also uses the text of the original story by A.S. Byatt (1994) “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye””