‘He is always feeling his way into a new role. … Every time he wakes it’s like the first morning on earth. … He is perpetually new. I know there is a lot of suffering that comes from that too. I can only imagine. But I think there is something fulfilling () for all of us in being able to make ritual use of forgetting and remembering.’[1] This blog concerns the play This Is Memorial Device based on David Keenan’s (2017) This Is Memorial Device: An Hallucinated Oral History of the Post-Punk Scene in Airdrie, Coatbridge and Environs 1978 – 86 London, Faber & Faber (Kindle ed.) seen at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on August 26th 2022 at the Wee Red Bar, Edinburgh College of Art. To @JustinCurley4.

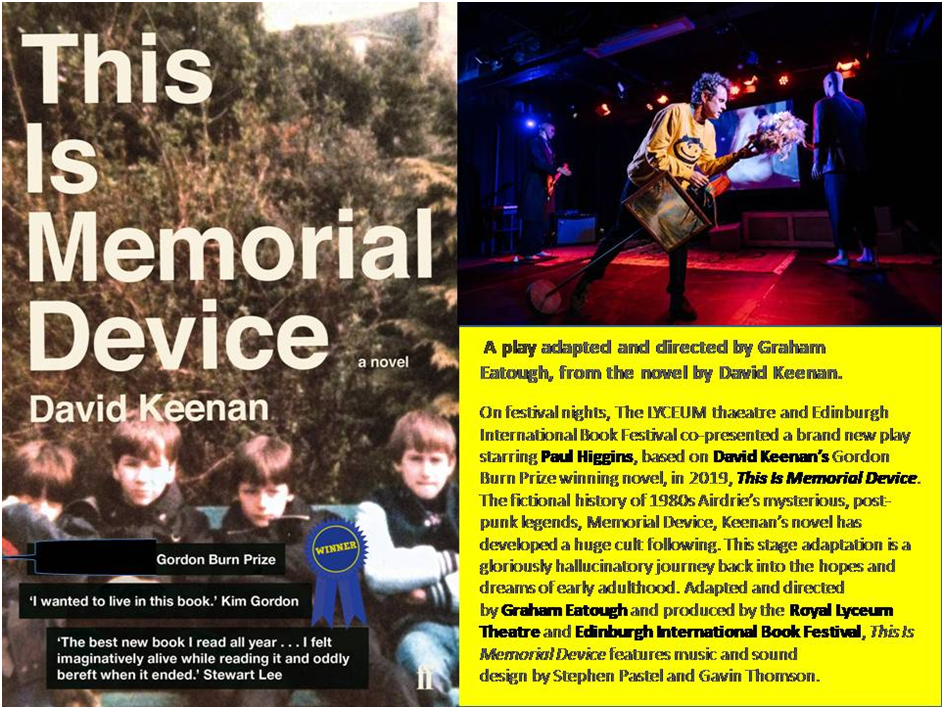

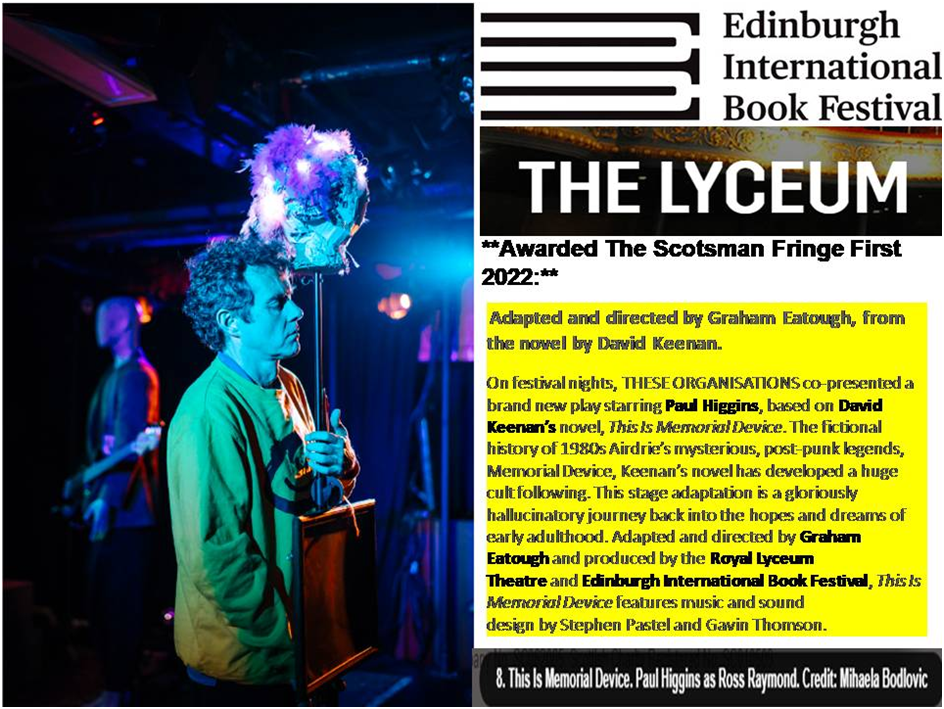

This blog is really a reflection on how art becomes itself in my own mind, even before I respond fully to it. From my own point of view, and I don’t want to generalise beyond that, there is a lot of nonsense talked about the quality of art as related only to its having an immediate effect on its viewer, unmediated by other frameworks for seeing it. This notion is itself a kind of theory of art based on the ‘art for art’s sake’ movement, but with even the requirement of that movement on educated response to issues of aesthetic form and design stripped away. In fact this blog could not be written at all if immediacy of effect were all that mattered. In a week of wonderful experiences of art of all kinds at Edinburgh, this play had no immediate positive effect on me – indeed to some extent my response, and that of my husband Geoff, rather veered to the negative. This was not art that made direct appeal on me at all – though some of its imagery and spoken and written language appealed enough to stick somewhere in my memory. The latter must be the case for my appreciation of the piece grew when my best friend Justin Curley, who saw it with us, explained not only why it might not have appealed to us and why it did to him.

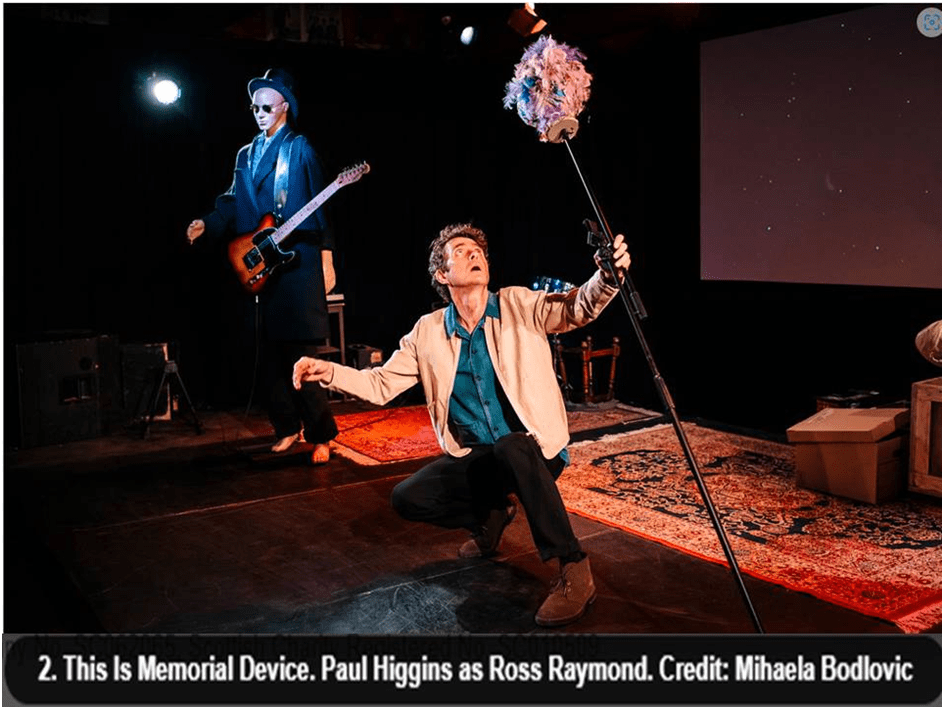

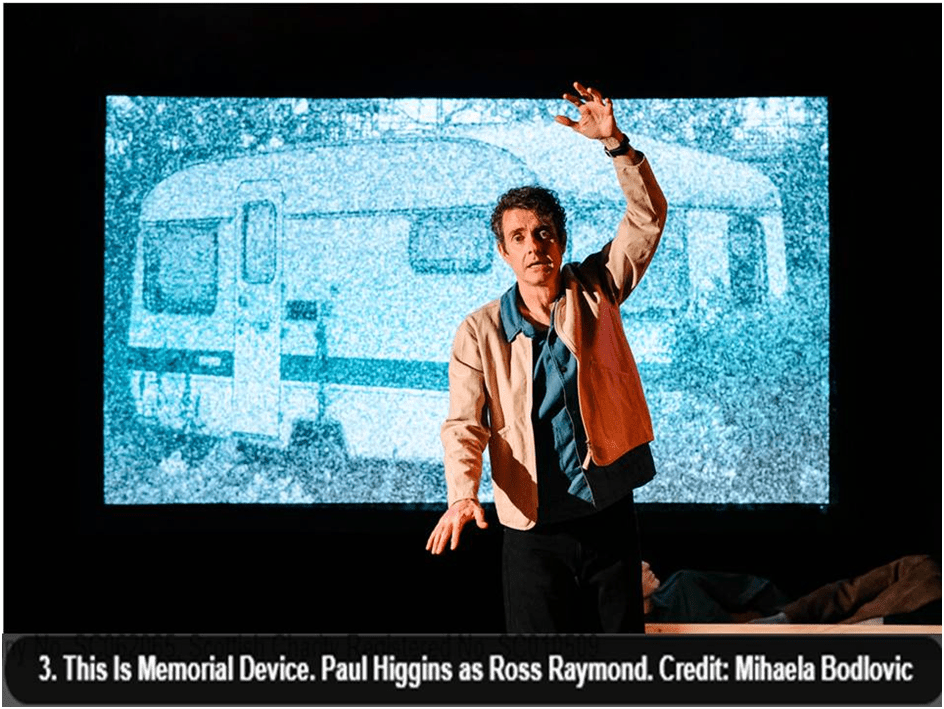

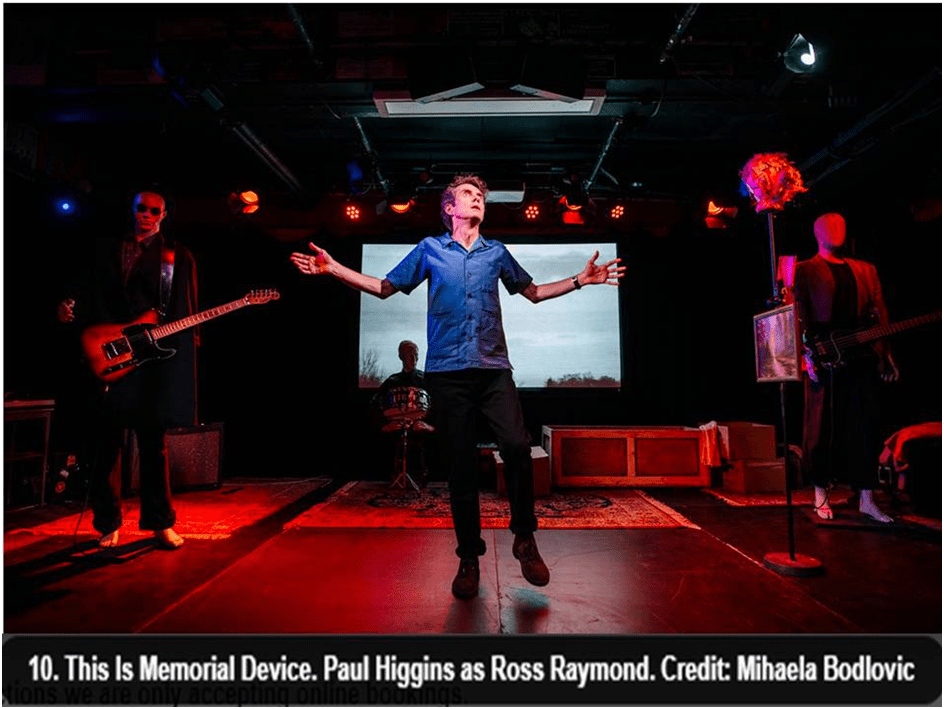

His case for the play, gently spoken but committed, was clearly immediate. He hugged the actor Paul Higgins after the event and that is certainly evidence of immediacy of stirred enthusiasm for what was communicated by Higgins and his interaction with audience, setting, music, audio-filmed ‘interviews’ with some other characters There was also interaction with film of events such as the fall of a tower of flats played (both in real time but on first seeing, in slow motion), photographic slides of written material or visual scenery, and, in main, with objects. The latter included variegated dummies built up from fragments in a large box representing the group Memorial Device, a landscape painting whose effect was spoken of as synonymous, if equally overwrought, and estranged from the normative, as a response, musical instruments and other odds and sods.

Justin was not alone in his enthusiasm. The audience roared approval and, before the audience left, Nick Barley (director of the International Book Festival) awarded Paul the certificate for the production’s success as a Fringe first in drama for 2022. It looks, doesn’t it, as if Geoff and I were missing something. How appreciated then was Justin’s gentle care for the explication of our different responses; because such explanations are far too often treated in ways that belittle one or other of the responses when they have diverged. He explained how the play spoke to him as a child of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, when, under the onslaught on civilized and communal values that was Thatcherism, the supposedly communal and national institutions and belief systems we believed in prior to this time had been reduced to facades. Musical heroes took the form of a substitute belief system and institution in the blanks created in public and private life, perhaps even the large black hole left by an emotionally and intellectually credible religion.

That ‘black hole’ of disbelief in divinely or enlightened scientific humanist ordained orders was created as a tangible nothingness to complement being, almost in parody of Heidegger and Sartre. That this ‘black hole’ has increased in size since the attempts to row back from it, even those of New Labour with its enforced accounting for Thatcherite values, is undeniable. It is the whole of governance and the ghostly simulacra of values in our current world now; where after the rule of a clown we face the absolute emptiness of an unsupportable right-wing rhetoric spouting puppet that is Liz Truss. Neither Geoff nor I were young enough in that period, he explained: our response to the political blank was not formative, said Justin in equally convincing manner. For his generation, growing up under the pressure of those blanks (as represented by the dramatis personae of this play) music acted as an ethereal ‘filler’. For some music was supplemented and embodied in groups of young people like themselves, the cult-like belief in music independent of institution – the indie band.

Dark places, empty spaces, and even black holes, certainly get realised in the play – although quotation here is from the source-book. One narrator makes the story focus on coming to terms with ‘the idea of dark places’, which, as a child, they were advised to ‘exorcise’ from their life. However, ‘when the time came I was forced to come face to face with my own madness. / Dopplegangers stalking my mind dressed as storm troopers’.[2] One witness of Memorial Device as a group describes his experience of them performing, as it absorbs and transcends a phase of cutting his own skin as a means of expressive self-harm: ‘I saw them play and my jaw was on the floor. I felt like I had been dating a five-foot high black hole’.[3] The black holes, which appear at least twice in the play and novel, owe less to their explanation in theoretical physics as to the notion of an all absorbing mysterious entity, which, in its absent presence is very hard to understand and often performs the role of making the paradoxical manifest. For instance, It is not clear what it would mean to ‘date’ a five-foot high black hole; but that it is an experience that defies clear comprehension is, at the very least, comprehensible. It is used earlier in the play and novel of Richard Curtis, the drummer in Memorial Device:

Back then Richard Curtis seemed like the dullest of the lot, it’s fair to say, maybe the most seemingly ordinary, is what I’m trying to say, in other words to an onlooker or a mere acquaintance or an audience member he may have come across as a square peg in a black hole, which wasn’t exactly true but which in a way made him the most eccentric of the lot,…[4]

Richard stretches credibility in every way: a ‘square peg in a round hole’ is a misfit but in a black hole, it is merely matter to be absorbed into lightless space. Trying to describe Richard necessitates that commitment to every descriptive word suggested in this prose is queried at the point of being used; phrases such as ‘seemingly’, ‘may have come across as’, ‘wasn’t exactly’, and ‘in a way’, for instance. And, as this monologue section on Richard continues, it becomes evident that the impossibility of defining him lies in the fact that the feelings, thoughts and sensations of his observers at this point also lack light in which to see themselves and their interior drivers. Strangely, I remember that my ears pricked up at this point in the play where the narrating actor sees Richard as eliciting queer sexual drives that he refuses to acknowledge or validate – in comprehensible time-space where such drives might be normatively assumed to be experienced:

There were times on the way home, and this is the only time it has happened to me in my life, I’m not gay, I’m not bisexual, I like women, as a rule, that I wanted to suck Richard’s cock, I can’t believe I’m saying this, and one night I came close to asking him – even though I wasn’t particularly attracted to him, he wasn’t my idea of handsome – outside of the flats on the main street, where I pictured pushing him up against the wall and going down on him in the light of the bin sheds. Do I regret not sucking his cock then and there? Ask me in another ten years.[5]

A prose style that deliberately obfuscates the reality of the expressions of events or feelings experienced in knowable space-time more than this passage does is hard to imagine. Its use of qualifiers, denials and contradictions of those denials (for this one and ‘only time’ feeling about a man hardly fits with reflections on what makes ‘my idea of handsome’) is almost symbolised by the dark light associated with ‘bin sheds’, for the very idea of such a ‘light’ is as obscured as the light swallowed up by a black hole in space-time.

These references support Justin’s notion that this play deals with the absence of belief systems and institutions which can be trusted as a means to organise life. What followed was his explanation that, for young people maturing in the period, veneration of musicians and ‘bands’ filled that gap. This almost matches Mark Fisher’s assertion about the play in his review in The Guardian that the play:

… captures the nerdish enthusiasm of a time in life when everything – books, poetry, songs, art – has a life-or-death intensity. “I’ve never been able to enjoy a paperback without wanting to commit myself to it forever,” says Raymond, not making a grandiose claim, just a statement of fact.[6]

Except I think Justin more clearly showed to me that this is not a psychological fact reproduced in the development of every young person through all periods and history and all cultures (as Fisher seems to suggest above) but one much more focused in the period of the play in the UK (1978 – 86). Moreover, Fisher’s words lack any degree of empathy (unlike the words of the play and novel themselves) as he describes the indie fan as characteristically a ‘nerd’ or, to use words he uses elsewhere in the review, a young man with a ‘boyish sense of wonder’ or ‘puppyish openness’. It is a truism to me that we ignore the spirit of the solutions to common problems of human existence proposed by the young at a cost to a society as a whole. What fills the holes and dark spaces of self-exploration maybe madness, and mysterious doubles or doppelgängers, but that effect of fullness is wider than Fisher suggests and includes things which remain the only solutions used by adults, immature and mature alike. These solutions are given names like the arts (and not music alone), sexual or personal relationships and religions or cults. In what follows I will try to illustrate those topics from the play’s text and / or source-novel.

As this list says, it is not only music of course, that represents accessible art for the young. The narrator, Ross Raymond, invests incredible belief in landscape painting. One of his paintings appears in the play hung around a pole, a phallic symbol at other times, ornamented with an electrically lighted head. This totem represents, in the first instance, the insane Memorial Device band leader, Lucas. Raymond in the source novel says that for him landscape painting became a way, like music, to ‘capture the same feeling of a portal. The feeling of stepping into a painting and seeing a painting’.[7] It was, for him, an infinitively recessive kind of painting – a way into itself. This is handled in the play using a ‘prop’ painting – one that you will see in some of the illustrative photographs (number 10 belowfor instance). The religious take on art here turns a black hole into an access point to the infinite and the ineffably meaningful, like God or the World of Ideal Forms in Plato. But in the end, painting is just a source of meaning to fill vacancy an assertion the ‘this shit actually means something to me’ in Raymond’s words.[8] In Lucas’s formulation the whole of surplus of meaning that life in itself lacks is bound in his music:

Music is always more than life, he wrote. His thoughts had been turned round. It’s life’s duty to live up to music, he wrote. When is life the equal of music, except in memory, in dreams?[9]

Sex, especially sex focused on male genitals, takes a similar form and the words cock, penis and dick are privileged in the source books, index, or ‘Navigational Aid’ (Appendix D in Kindle edition). In the source book but inevitably missing in quite this fullness in the play (as far as I can remember) is the story of how fan Paprika Jones transcended a ‘reality’ which, in which she had been:

brought up to believe that every indulgence was punishment, that every time I listened to my heart I would be beaten down … as if all that reality desired was your complete debasement and obedience and that a confession of guilt obviated the necessity of breaking you forever.[10]

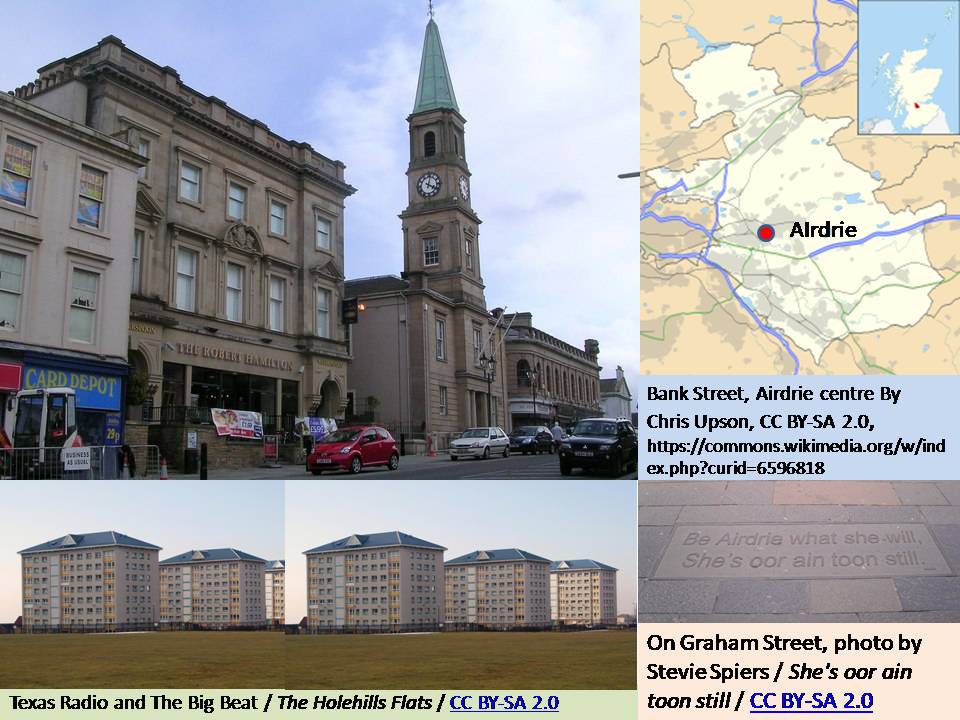

The description here of reality poses it as a debased institutional religion, the answer to which she goes on to say is a series, potentially endless, of variegated ‘cock’, for ‘it takes a lot of cocks to hammer it into your head’. Those cocks played the role of rhythm and counterpoint in her life, heard first in soundtracks from Velvet Underground, which made more sense than ‘death in life of a suburban marriage’. The cocks she then takes in – filling, as it were, her black hole with the music of the artistic men to which they belonged. This embodied music, unlike visual art, fashion and books which were less open and available, was there for all in the ‘local scene’ of Airdrie that was ‘an international scene in microcosm’.

Within that scene she finds ‘sex’ (with musicians) ‘never let me down’. She describes the range of penises that sex with musicians involved – a range of size or type (even dildos handled by women) up to an experience (with ‘Rodney, the Rod’) of an ‘immaculate cock’.[11] The term ‘immaculate’ with its range from cleanliness to religious spotlessness pretending to the absence of sex itself in divine conception shows the constant interplay between religion and other sources of sought transcendence of ‘dark spaces’. For me this piece adds to the effects of the play elsewhere of queer sex (pretend or real) where, for instance guitarist Patty does not care if his behaviour can be read as that of a ‘three-speed’ (a ‘three-speed gear, a queer’ that is).[12] Sex between male pop group members and their fans, which Raymond sees embedded in drummer Richard Curtis, but more of that later, transforms the semantics of sex, as I hope I can show, though this part I import into Justin’s more objective reading of the play’s effect.

Cultish religions are constantly evoked in both music and sex in the source novel and the play. Music is tied to the experience of a mix of emotions associated with humanity’s complex relation to religious ideals – guilt for instance and its transcendence – paradoxically sometimes simultaneously as many religions suggest possible: ‘songs that were written out of guilt alone, songs that were meant to salvage guilty feelings or salve guilty feelings, one or the other, …’.[13] Songs elevate lust to love, and nothingness (qua Heidegger and Sartre) to something, even if it turns out that ‘something’ is merely looking at ‘ordinariness’ somewhat differently, queerly or madly.

…, just crazy stuff that made no sense and that’s when it struck me. He’s singing about nothing. Fuck me. He’s writing a song about nothing. It’s the only thing that songs haven’t been written about. D’you get me? And it was like a love song. It was like he was singing a song to something that was lacking in love that even the mention of its name would bring it back to life and we would all notice it and fall in love with it like a prom queen or a movie star. Oh god every bit of nonsense was like a poem to nothing from the depths of his heart to the depths of his heart. (my italics)[14]

That elision of the name of god with prom queens and movie stare tells us a lot and we will hear it a lot in the play, even if only as exclamations so common to modern culture, where God’s name is so often invoked in relation to things God might seen as merely passing fads. Relationships, music (standing for art in general) and religion are confounded and related to the very ordinary experience of all in the period of time evoked. So often this ordinariness is a dream of people (but often just men in bands) freely injecting into each other free of guilt induced by false religion (in the spirit of these songs of love) and trying, as was Justin’s main point to put the spiritual back into a life made entirely material by Thatcherism. Claire Lune (obviously a bow to Chopin) talking about the rumours of musician Remy’s being ‘a poofter … dismissed from college for dalliances with young boys’, says beautifully:

I’m into things meaning things, if that’s what you’re getting at ____ Symbolism goes way beyond that _____ he said: way beyond the long blank _______. … my boys were never less than charming or seductive … ___ my boys were so free and so self-assured and so free so guilt-free _____ That was a big thing with me ____ guilt ____ all my life ____ … ____ I need a shot of them or something ____ an inoculation ____ an inoculation against spirit-devouring life as practised in the west coast of Scotland _____[15]

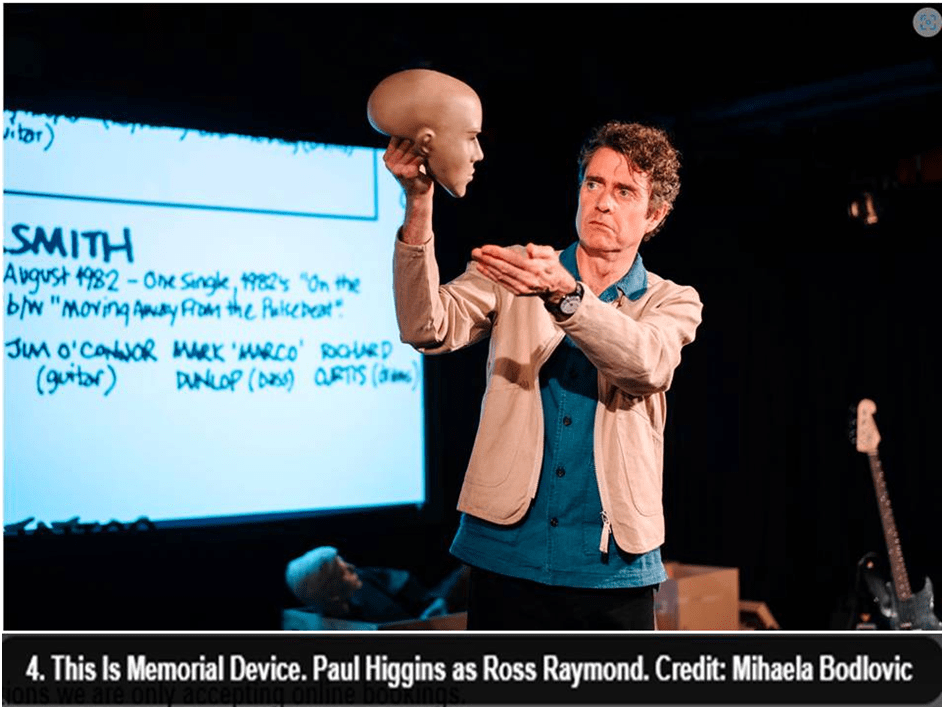

In Scottish terms lifeless materialism with an edge of even more lifeless Protestant religion is synonymous with the ‘west coast of Scotland’ which, like Thatcherism and perhaps its neoliberal Adam-Smith derived false ‘heart’. Photograph 4 above shows Higgins miming such-like reflections almost as if he were Hamlet with the skull of Yorick. The series of ‘black holes’, ‘dark places’ and other ‘blanks’ are synonymous I would say, and perhaps Justin would too, with the spirit-devouring life of Thatcherism. I think this is why the play and source book keep on emphasising the local (Airdrie in short) as the locus of new meaning that touches on the international. This may be because national politics in the period represented in the play – which meant then politics of the Union with England – was so sorely tainted by renascent neoliberal selfishness (especially – I and Justin would say – in England). Throughout the musical works dealt with in the play strain to find meaning in bog-standard ordinary life, that which is special and extraordinary because it is transcendently ordinary. That, by the way, is how Raymond explains his attraction to Richard and the desire to take him into himself. Richard is attractive because ‘his ordinariness was attractive’. He offered a ‘portal’ (as landscape paintings did) from ‘my own inherited feelings of ordinariness’ to a new realisation that neither he nor Richard ‘were ordinary’ at all: ‘Which in a way is the whole point of the story’ (my italics).[16]

How does all the above translate into different art forms. In the source novel it requires a re-thinking of narrative form, one that tends to the displacement of conventional time and space while taking place in the most ordinary of settings. It leads, for instance, to recognition that story-telling can often be too assertively neat. When Lucas writes ‘there was no significance’ in the day itself he picked to discourse about it or order. It can be sampled ‘at random’ and is ‘indecipherable anyway’. That is perhaps because:

We invent endings really, which is what it says to me. There is no resolution, no fixed beginning, no neatly tied-up end. People have tried to read into it so much, but it was just a moment passing.[17]

The rejection of teleology here (theories, that is, concerned with ‘ends’ whether as completions or purposes – like the will of God) is a rejection of conventional and institutional religion, even in artistic symbolism and an embrace of the mundane ordinary moment in time and space as the paradoxical basis of the extraordinary. The nearest Raymond gets to discussing this ‘philosophically’ is below. The passage recalls the rebellion of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost and again invokes the concept of a portal to the infinite (the religious momentum in life):

What if the very idea of the will of God exists as some kind of tissue tiger?[18] … What if you refuse it altogether? What if this insult, this seeing through of a ruse, this act of rebellion (whatever you want to call it) affords you access to the next level, … and finally you are able to live your life as written (in history and in time over again), but this time outside of mind, without judgement and beyond understanding. … back then, when we were young, once, forever, it seemed like a genuine possibility.[19]

That Justin noticed the specificity of this, whilst me and Geoff didn’t, shows how specific this art is to a period I think. I am convinced anyway! Of course in this piece I also sail off on my own boat on the queer issues (don’t blame Justin!). Its significance for storytelling in both source book and the play’s monologue sections is that story must be compounded from memories of the past, projective wishes as well as the present:

… Lucas is always performing, in a way. Because of his condition. He is always feeling his way into a new role. Every minute of the day. … Every time he wakes it’s like the first morning on earth. … He is perpetually new. I know there is a lot of suffering that comes from that too. I can only imagine. But I think there is something fulfilling for Lucas for all of us in being able to make ritual use of forgetting and remembering.[20]

Performance of stories is not necessarily a conventional ordering of events in a linear way, reproduction of scripted roles, nor is it looking for conventional beginnings and ends. It is intensely stressful form of recreation – both play and renewal. To translate the theatrical metaphors from written narrative form to an actual performance clearly the wonderful Graham Eatough had to think carefully about the ‘here and now’ he represented as locally. Of course video and photographs can recreate Airdrie in part, but better still Eatough utilised the venue as brilliantly discussed by Hugh Simpson:

Adapter-director Graham Eatough has created a stage version that is at once intimate and expansive, true to the source while having its own definite identity.

The setting of the Art College’s Wee Red Bar, host to countless gigs by up-and-comers, never-weres and did-they-really-existers, is perfect. Paul Higgins brilliantly plays Ross Raymond, chronicler of Memorial Device, inviting us all into his reminiscences.

There is no fourth wall here, with Higgins in touching distance and regarding us as fellow acolytes of the band, here to remember them.[21]

The here-and-now is the moment of watching, as Higgins brought the present audience into the action by clever use of the aisle and encompassing gestures performed within it as below.

I do hope this piece tours because it deserves the kind of audience Justin represented. I failed to respond, a bit like the imagined original audiences of the group in its early days in which ‘no one was paying them the slightest attention’, but because for those in the know like Raymond, and it seems Justin but not me, ‘it was compulsive’, whilst the band ‘seemed completely unaware of the lack of the response’ for those who did not understand, at least immediately.[22] As Simpson concludes his review, this show is ‘mostly it’s for anyone who believes that art can inspire, unite and transcend.

See it if you. Ask Justin Curley for help if you need to. As I did. Lol.

All the best

Steve

[1] David Keenan (2017:21) This Is Memorial Device: A Hallucinated Oral History of the Post-Punk Scene in Airdrie, Coatbridge and Environs 1978 – 86 London, Faber & Faber (Kindle ed.)

[2] David Keenan (2017:251) This Is Memorial Device: A Hallucinated Oral History of the Post-Punk Scene in Airdrie, Coatbridge and Environs 1978 – 86 London, Faber & Faber (Kindle ed.)

[3] ibid:192

[4] Ibid: 35

[5] Ibid: 38

[6] Mark Fisher (2022) ‘This Is Memorial Device review – memories of fictional indie heroes burn brightly’ in The Guardian online (Wed 17 Aug 2022 20.00 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/aug/17/this-is-memorial-device-review-wee-red-bar-edinburgh

[7] Keenan op.cit: 42f.

[8] Ibid: 44

[9] Ibid: 145

[10] Ibid: 245

[11] Ibid: 246 – 249.

[12] Ibid: 190

[13] Ibid 104f.

[14] Ibid: 105f.

[15] Ibid: 215f (my omissions … but author’s italics and underscores).

[16] Ibid: 39

[17] Ibid: 111

[18] I take it that this phrase is a clever variation on ‘paper tiger’ (defined in ‘paper tiger’: meaning and origin – word histories) but clearly indicating even flimsier paper material.

[19] Keenan op. cit: 66

[20] ibid:21

[21] Hugh Simpson (2022) ‘The Lyceum’s extraordinary run of success at this year’s festivals continues with This Is Memorial Device, their collaboration with the Book Festival’ in All Edinburgh Theatre (online). Available at: https://www.alledinburghtheatre.com/this-is-memorial-device-edinburgh-international-book-festival-lyceum-review-2022/

[22] Ibid: 21