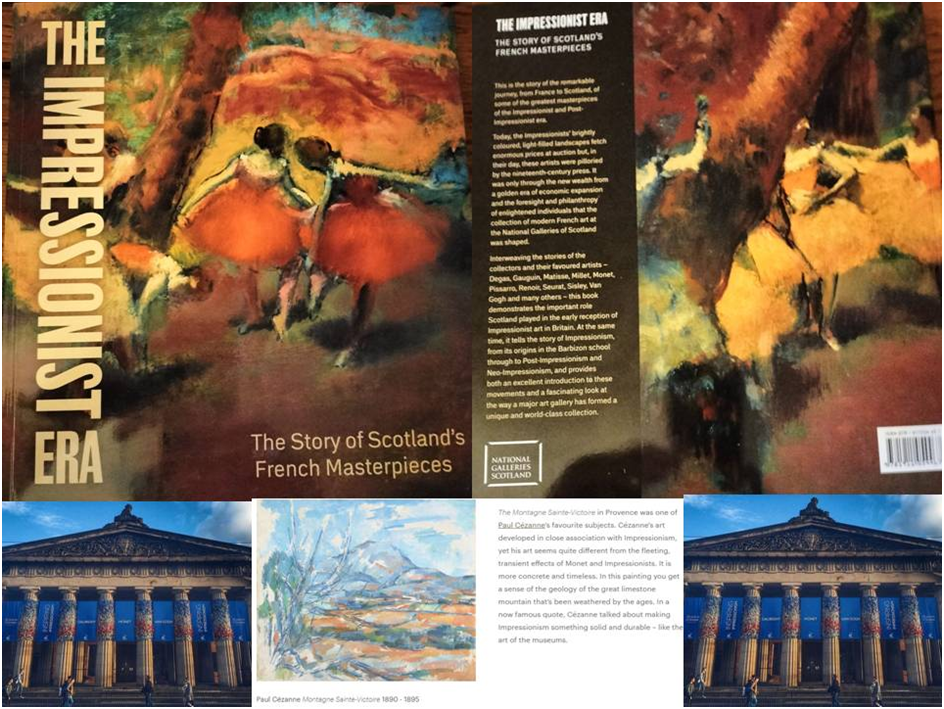

In 1893 the ‘critic R.A. M. Stevenson observed’: “I feel the real lover of pictures preserves them from dangerous encounters. … he jealously guards his pictures from improper companions and riotous debauches and untrammelled colour”.[1] This blog examines why art galleries are looking again at the tastes of the private and institutional collectors of art in order to deepen understanding the reception of art through its history. This blog reflects on an 2022 exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery seen at 2.00 p.m. on Thursday 25th August and the catalogue of the exhibition: Francis Fowle (Ed.) [2021] The Impressionist Era: The Story of Scotland’s French Masterpieces Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland.

I visited this exhibition whilst at the Festival this year with Geoff, my husband, and my best friend, Justin Curley. As national art institutions feel the increasing ferocity of an economy out of control and the loss of political governance of arts and culture ushered in by the most right wing government ever to disgrace British politics, I think we will become increasingly subject to exhibitions at every level in which galleries live on their cultural capital and, whenever possible, curate exhibitions about art they already own rather than temporarily housing art from global collections. This is the pre-eminently the case here and it explains what some may see as an incoherence in the collection or mismatch between its descriptive title and its contents. It would though be a great mistake, based on a misreading of the title of this exhibition, to visit it primarily to understand the movement in art often labelled ‘impressionist’. Granted that this title arose from accident of antagonistic critical labelling, it has still been usual to make something of a distinction between impressionist and expressionist art – the one capturing how reality is seen and ‘reproduced’, the other ignoring reality other than as a source for the expression of the subjective or, in some other way, abstract conception of what art, life and reality mean to the artist. In this exhibition both ideas are important and can be applied in ways that do damage to any belief in the ontological reality of the term ‘Impressionist painting’.

Many paintings in here are either often labelled impressionist or expressionist and some, like the Nabi school represented by Vuillard and Bonnard, fit into neither. The exhibition ends with Matisse whose example gives credence to neither category nor any other, including that of Fauvism, probably the silliest of art historical labels. One oil painting from Cézanne stands alone in significance to me (although I lean to a few such others from Van Gogh and Gauguin also). They all defy the meaningfulness of those critical labels too (the label of Post-Impressionist they often get tells us very little). At the end of the ‘period’ covered by the exhibition(and this too is vaguely defined) the contradictions between the visitor’s search for coherence in the collection and the random discovery of individual paintings with little in common with pictures near to each of them is even more pronounced. Do we search in vain for common factors between a socially feminine interior in Vuillard, a classic cubist candle-piece by Braque & the emotion of Picasso’s Blue Period? That is to say nothing of a final room of beautiful Matisse cut-outs, which feels appended to the exhibition- beautiful and interesting appendage though it be.

However, lets return now to the incredible painting by Cezanne mentioned already above and illustrated below. This painting haunted me because it utilises white space like no other painting on show here and is insufficiently described merely as being influential on followers because it uses geometric shapes and blocks and dabs of colour in its design. It is the painting which moved me most and yet I never wanted or needed to label it as Post-Impressionist or by any other term. On the other hand, we probably need those labels since they do tell us somewhat of the historical reception of the paintings in critical theory and this is at least one factor in the shaping of a collector’s view of why they believe their collection is a coherent one – for coherence is sometimes valued by some collectors as a sign of the integrity of their taste, interests or relevance to the values of their own ‘modernity’ or ‘traditionalism’ or both at the same time.

It is impossible in terms of this exhibition to diminish in this respect the importance of Roger Fry; described in the catalogue as ‘the leading British critic of the period’.[2] But the title of this exhibition demands that we see that Impressionist is merely a convenient label for a hegemonic taste in art and certain artistic methods and perceptual frameworks of the period. It gives its name in this exhibition to a period of time only – an era (a usefully vaguer term for time period), of which the pictures, their reception, purchase and later fate (in becoming the property of the Scottish nation’s Gallery) tell the ‘story’. This has enormous advantages. It strikes me that being encouraged to see Monet, for instance, as an Impressionist, really does oversimplify his art and its methodologies. In this exhibition I saw more similarity to Van Gogh (whom I notionally always felt I preferred to Monet who, in 2018, seemed less than his reputation in my opinion as recorded here) than I had thought.

What strikes here when seen in the flesh is the absoluteness of the uses of impasto, especially in the white lining of the clouds and the tips of surf waves but as well in both the sky’s and sea’s overall tonal variations (created by thickness as well as colour of the fleshy oils). These do not merely create effects of light as a visual impression but also increase the density of the painting as an object – refusing mere surface impressions and emphasising a sentient and emotional expressive whole that is as near symbolism as it is the capture of observed reality. In brief, it too does what Van Gogh and Gauguin do, if less obviously so. This is clearer if we examine photographs of details from the picture where the brushstroke’s movement is palpable – in clear swirls as well as dabs of different weight and carriage across the painting.

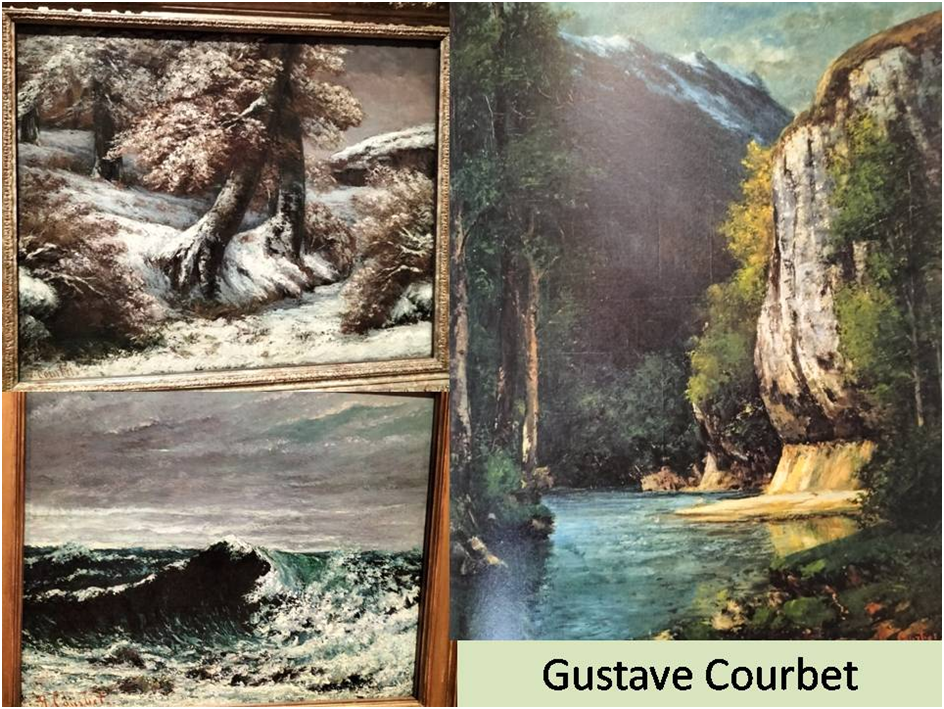

Other advantages of the vaguely defined timelines which are the sole criteria for inclusion of pieces from the collection are possible for other viewers, especially any who would be glad to see a reassessment of artists like Boudin, Sisley and Pissarro, who no doubt are greater painters than my undoubted admiration covers but which have not yet attracted me to them. Possibly I need guidance and assistance here. This exhibition will not fulfil that function for me for its interest is in describing how the taste of others built this specific national collection. But some may find revelation from the company these pictures keep as I did with the Monet and in seeing three very fine Courbet pictures.

Seeing Courbet in this company is salutary, especially in forms that were neither figurative nor able to be classified as social realism. These paintings raise expression to heights that make nonsense of a comparison to the creation of visual impressions.

For these paintings, however visually beautiful the scene conveyed, carry a sensation to my view that is almost visceral – of weight for instance – that goes beyond the visual. They call out to us to find cognitive models of themselves that modify some conventional idea – not least the revision of Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) painting.[3] I think Nature is an expressed idea here in ways it never is quite in the classic impressionists who, in my opinion, divorce perceived reality often from its ideation in cognition, if not emotion. To see them here is to be able to feel the distinctness of the artist and to make comparison of what seem substantially lighter in the world of Boudin, for instance.

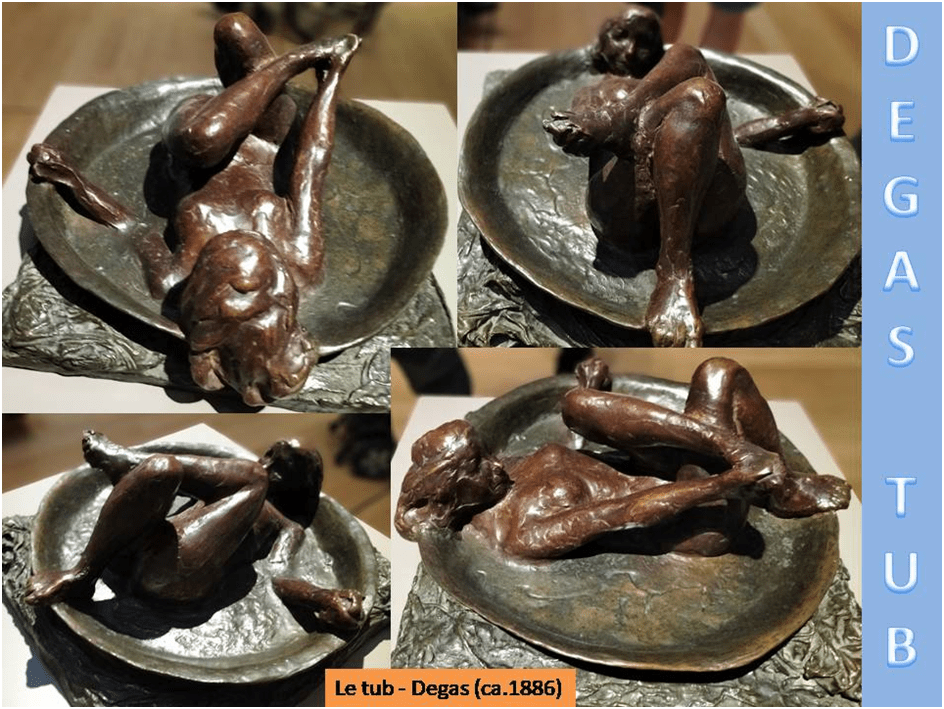

This density of approach which seeks ideas of submerged depth and the weight of the bodies of stuff is more obvious in Degas’ Le Tub (c. 1886) which involves the viewer in the search for perspectives, and plays with the boundaries of the work of art.

It is not possible to convey all the beauties and wonder of this exhibition. I think this comes precisely because the distinctions between works are so rich that they cast themselves into comparisons between works of art often seen as more like each other. I felt I saw things anew. Sometimes I discovered a new beauty that I could compare to no other picture here, such as Raoul Dufy’s The Wheatfield (1929).

This picture may superficially recall Van Gogh or the colourist freedom from impression of Gauguin (whose Brittany paintings refresh you on seeing them again with the boldness of colour choices). It may suggest Matisse in the ability to use a colour range that falls into blocks rather than within drawn lines. But it is very much itself and it is beautiful. In the language of R.M. Stevenson cited from the catalogue in my title it is one of many ‘dangerous encounters’, an ‘improper companion’ or ‘riotous debauch of untrammelled colour’. And an exhibition like this makes for many strange bedfellows and queering of our boundaries of safety with pictures and desire for either coherence, harmony or the unchallengingly recognisable in the world. You will notice many other things than I but do go. You will notice much and maybe you will also feel, if you are capable of it, untrammelled for once.

All the best,

Steve

[1] Francis Fowle (Ed.) [2021: 39] The Impressionist Era: The Story of Scotland’s French Masterpieces Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland

[2] Ibid: 41

[3] See https://www.artic.edu/artworks/24645/under-the-wave-off-kanagawa-kanagawa-oki-nami-ura-also-known-as-the-great-wave-from-the-series-thirty-six-views-of-mount-fuji-fugaku-sanjurokkei