Queerly Dedicated: seeing plays about queer sexualities at Edinburgh Festival in 2022: covering a visit from 20th – 27th August 2022.

Every year we come to Edinburgh, we see as many plays about queer sexuality as the Fringe offers. The writers always have a point to drive home and the companies which commission or perform the plays often have used the process of preparation for Edinburgh as their access to learning about some aspect of how issues of sex/gender, stereotyping and identity (sometimes – I would say often – the same process is play in both of these processes) and the performance of sexual and/or romantic attraction between men. I often ponder (but not too deeply for this is a holiday) whether the plays register change in the way queer people see themselves and the place of sex and attraction to others in their lives.

So here are the plays seen:

- Mon 22 August 20.15 Let’s Try Gay at Annexe at the Space @ Symposium Hall

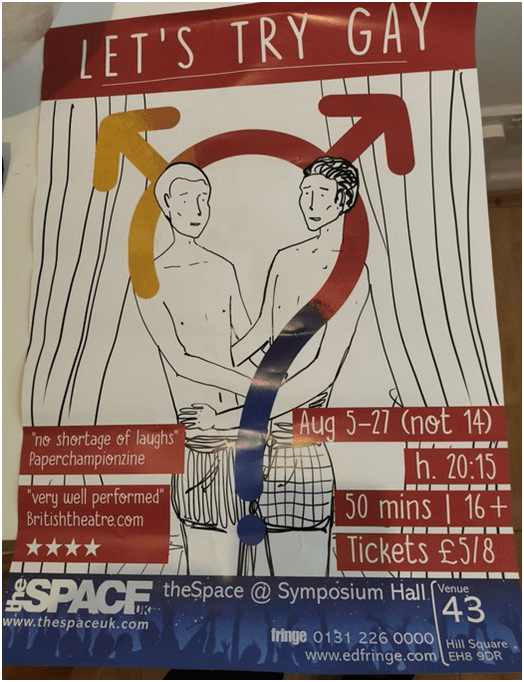

- Wed 24 August 16.30 Wilf at Traverse 1, 10 Cambridge Street.

- Wed 24 August 20.45 Gayboys at Old Lab at Summerhall Festival

- Fri 26 August 12.00 Wreckage at Red Lecture Theatre at Summerhall Festival

Let’s Try Gay

The play is set in a Paris hotel room dominated by a double-bed in which two life-long friends (both Italians) meet to complete the demands of a bet they set with two young women at a drunken party that they dare not film a ‘gay porn’ video starring themselves. The friends assert their presumed ‘obvious’ heterosexuality, raising laughs a plenty from the audience, presumably at the absurdity of the notion. We know, after all, as little about what makes heteronormative ‘obvious’ as we do of what marks queerness, since the difference between people in and between each category are more numerous than the similarities within each of the binaries.

Of course, it’s funny too because of the way the men perform their supposed simulation of the approach to having sex together – the countdowns to removing their tops and their jeans. They try the same approach to their underpants but it fails at the last number – the one after a faltering ‘two and a half’. There the men remain in respectively tight black Calvin Kleins by one and tighter blue briefs with numerous bananas printed on them for the other – ‘too many bananas’ says the first to a huge laugh from the audience. A lot of the humour was focused on the visible bulges of undivulged (in full nakedness) ‘pee-pees’ (as the lads name them as they sneak a peak of each other’s). However, the show triumphs because it is about men learning to put sex in its place by raising it from the large and capacious gutter of fear and loathing cultures of Western masculinity place it in and putting it in a place where it is respected.

For the men do, we are to believe, sleep with each other but talk about this in terms of how it fits in their network of inter-relationships, the single man (the unmarried artist) saying as the married other says he must now tell his wife that he should not promise more than he can give. It is a beautiful moment. All gay porn is forgotten as relationship predominates. Perhaps, this is because what we see before they just sleep together is not ‘gay’ porn at all but a masculine dream of potency that is not sex really but power used not only against women but men too. Perhaps constructing sex as just the aggressive penetration of one person by another also both constructs and enforces the weakness of a passive other within the sex act. The hilarious exchange (early in the play), about who ‘f…ks’ whom, is probably more important than we might think.

See the play.

Wilf

Wilf by writer, James Ley, covers the process and outcome of falling in love in rebound from an abusive queer relationship. However, it differs from other plays on that subject by the object of that love being a car, named Wilf. The lovers are pictured on the play script cover and the mix of the absurd, the uncomfortable (in, for instance, the voyeuristic examination of sex between lovers) and the parodic is well captured in the picture. Wilf is here caressed and pleasured with alcohol and mixers by Calvin, played by Michael Dylan, but the play does not stop at such moments of passive abandonment to each other and gets to the moment just before the scene blacks out where Calvin sheathes Wilf’s gear stick in a condom and …. well, the rest has to be imagined as Calvin’s back turns to us. We guess because, in a moment of hilarious guilt that Calvin feels after the event he tells us about it, and what lead him to abandon himself to Wilf.

This is a play of slapstick where the slaps and the sticky are often a little too visualised – such that we gross out in the excess of it all while relishing its bathetic humour. For before and after Wilf, Calvin tries out multiple sexual encounters or fantasies about love for hard men, with varying success (even in his fantasies except where buckets of ejaculate are literally poured over him symbolically) but with much humour, not least because all these multiple men are played by the same person: Neil John Gibson. Meanwhile Calvin is psychoanalysed by Thelma, played by Irene Allan – an expert in Fritz Perls’ ‘empty chair technique but who has left psychotherapy because she too oft goes too far in acting out her patients’ fantasies.

Much of the play is about the objectification of sexual and amative fantasy in which objects replace the inconvenient aggressions and assertions of human significant others. That these objects often have the same aggressions and selfish assertions projected onto them by dependent lovers is highly significant. It is a play of the significance of Schnitzler’s La Ronde in a by now thoroughly queer and postmodernist context. This is not the only play that at Edinburgh that explores the role of objectification in fantasies of the desired other. In fact I find it significant of what I think is a maturing of queer art away from over-positive images and towards a more mature understanding of the range of values implied in queer love – neither wholly positive or negative as binary thinking constantly would otherwise have it.

Calvin has to learn to love Frank but it takes time to work through the intoxications of fast pace, multitudinous variety and careless excess (none of which Frank claims for himself) before Calvin matures from fantasies represented those buckets of ejaculate poured upon him on more than one occasion. Its purpose speaks through near satirical humour and the play lives through the pace and variety it rejects at its end. As a result, it is a morally rich comedy that is genuinely funny. Played by exceptional actors, this is a play to see and it should (I hope) tour. And it’s so wonderfully self-referring that it keeps the avenues between art and life very truly open. At the end, Calvin says:

Maybe me and Frank kind of start seeing each other:

Maybe we come up with an idea for a show.

Maybe I wasn’t serious, but Frank is.

Maybe we call it Wilf.

Maybe I’m in it.

Maybe I play myself.[1]

Gayboys

Gayboys is a play that is quite unlike our normative expectations of a play. First its only words come from the lyrics of some of the music played to accompany the action – words which sometimes the actors voice-mime to, and which, together with the timbre and feel of the music get translated into British Sign Language by an on-stage signer dressed in exactly the same costume as the two main actors (whom we see above in the show poster).

It plays out through choreography to music, sound and light effects, with the use of a basic set, including a white screen to the rear of the stage that can be utilised as a place to which the actors exit the gaze of the audience and enter again into it. There is for part of the duration a white box in front of the screen which can enact various roles including a plinth for statuesque poses or energetic disco-dances as provided for the more gregarious at some gay clubs for men (as well as being an object metamorphosed in performance into other things). Likewise other objects are utilised to show the means by which gay ‘love’ and sex is absorbed into consumer culture and increasingly available for commodification and fetishisation. This is, as we can intuit from what I say above, also a theme of Wilf, and this play too aims to show the maturity of insight of modern queer culture into the fetish that is a ‘gayboy’, one of the many stereotypes of identity that oversimplify the non-normative in sex and love.

As the description in the publicity pictured above shows the boys offer themselves to the viewer’s gaze upon this play in similar ways as used to be analysed in images of women in commercial and popular culture (by John Berger in the classic text Ways of Seeing for instance). We are asked to see WHAT is exactly being consumed in such visible embodiments of behaviour, thought and feeling. For we are what we consume surely and introject it uncritically if we do not reflect upon it. And in this play we are constantly invited to reflect on what we see, hear and take in in other ways. Only in doing this will queer sex mature into the world as something not at the beck and call of the cash nexus of commodity capitalism. How they achieve these meanings I am too ignorant of the basics of the arts used to analyse but I believe they do.

See the piece. It is funny, haunting and an ethical breakthrough in the self-critique (a loving one, as the best self-critique is) of queer culture.

Wreckage

This play is probably the least radical of the plays we saw but not the less important. It charts a relationship between two men, Sam and Noel (and the mother of Noel), and another man, Christian, who enters the story after Noel’s tragic death in a brutal car accident in which Noel and the car’s wreck enter the Cam at Cambridge to take on a fluid and ghostly existence. That is because they both become projections and internalisations of another kind of wreckage – that of love-in-memory. Part ghost, part projection of Sam’s conflicting moods Noel (the actor also plays Christian), Noel in the main part of the play has many personalities that seem to be, in part, the many ways in which Sam tries to make sense of the process of loss, change, memory and forgetting.

As a result this play too enters the ranks of plays that have matured our experience of gay love at the level of the ethics of relationships. It is beautiful and will make you cry and make you hopeful. The hope isn’t an empty enforced cheerfulness and this play is brutal in asking the audience to experience the durations of change in psychological and artistically represented serial time and its circulations in the body as the ebb and flow of remembered desire. We feel the pain of waiting, expectation, frustration and even of the tedium of empty time, momentarily for the latter at the least. It is a funny play with a brilliant way of showing intrapersonal conflict as if it were interpersonal conflict – which is, I believe, the the main problem of relationships anyway in real life, queer or otherwise. Its psychological grasp stops sort of really exploring wherein the personal is also deeply political – in issues of queer and interracial conflict, all of which were open for exploration, but this is a beautiful and deeply moving play.

It was a fine ending to seeing a series of queer plays where maturity of response was more important than over-simple affirmations of ‘identity’. We are grown up now. See the evidence if you can.

All the best

Steve

[1] James Ley (2022: 73) Wilf London, Methuen Drama