‘But when I think Oh William!, don’t I mean Oh Lucy too? / Don’t I mean Oh Everyone, Oh dear Everybody in this whole wide world, we do not know anybody, not even ourselves!’[1] This blog is about Elizabeth Strout (2021) ‘Oh William!’, New York & London, Viking, Penguin Books. Note that it CONTAINS SPOILERS: so do not read if you do not like that: BOOKER REFLECTIONS SHORTLIST 2022.

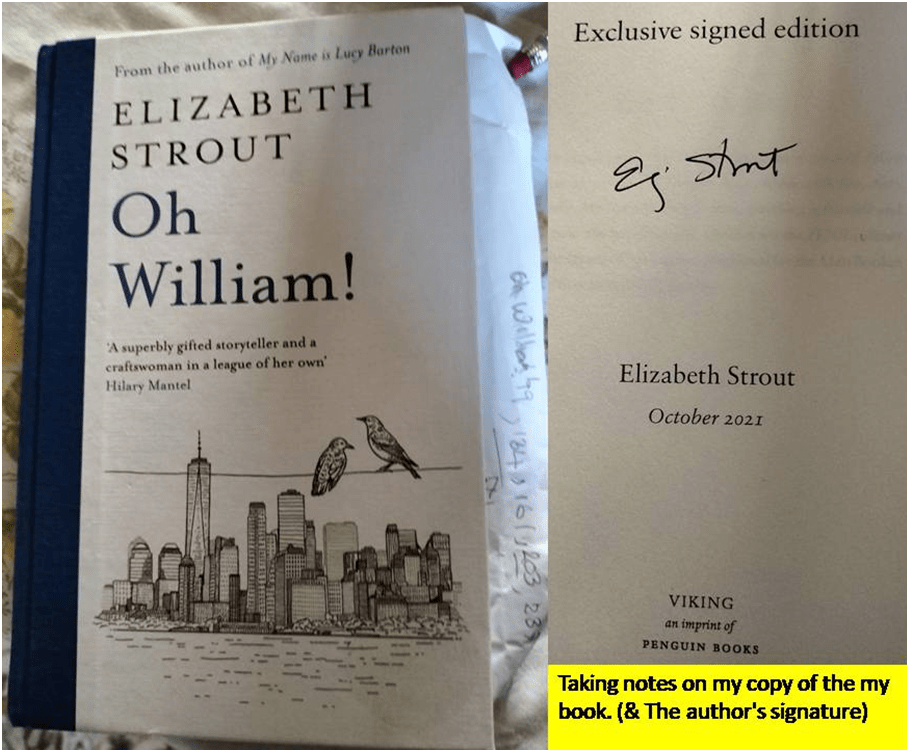

When I first heard that Elizabeth Strout’s 2021 novel Oh William! was on the Booker longlist I somewhat sighed despite a vast admiration for My Name is Lucy Barton. Even more deep was the sigh when I realised that this novel too was an extension of the fictional autobiography mode of that earlier (and other novels) in which the character, Lucy Barton, narrates, in the first person, parts of her life-story and ponders its significance. Why? Because clearly Strout is a modern master of the novel and is admired immensely by other novelists, including well revered ones. As I pondered this, I thought that maybe this is for the same reason that other great masters from the history of the novel have sometimes been less liked than admired, as if despite the tremendous artistry of their method, their content left one feeling somewhat that the worlds they represented were overly limited to apply to the imaginative and practical needs of many people at the same time as the need for something beautifully wrought so often expressed by the literary connoisseur. And sometimes I feel it is because the characters come from a limited socio-economic background and social class.

Jane Austen in December 1816, who is often criticised thus, is purported to have described her method, in a letter to her nephew, about his planned novel with ‘spirited Sketches full of Variety and Glow’, as like painting on a ‘little bit (two inches wide) of ivory on which I work with so fine a brush, as produces little effect after much labour?’.[2] As ironic as this comment must be from a master of the novel to a loved relative who is solely an amateur at her art, it mirrors the irritation of many, such as Charlotte Brontë, at the huge effects created by a ‘smallness’ of her fine techniques and settings.

Strout, of course, does not confine the external geography of her novels for, as this novel makes clear, this is not just the story of a few atypical American bohemians but “a very American story”, comprising the history of a white bourgeois America. In it the USA faces up to its humble European past, and its part in an European war, the spread of the nation and of the core myths of the American dream negotiating between origins that look small in retrospect and a success that is large in expectation and (but only sometimes and that rarely) fulfilment. In such stories origins are not only mean (‘tiny’ in both size – like the homes of the poor – but in spirit) but are about coming ‘from poverty’ (indeed from ‘Nothing’) before achieving success and largesse of personality and economic status.[3] But the materials it uses are as tiny as that strip of rich ivory, filled out by a disguised and hidden mastery with language, dialogue and a kind of innovative play with narrative time. It is sometimes easy to miss the larger resonance of her novel’s themes I feel in the fineness of the novel’s technique. This novel in particular touches on a socio-economic range across parts of American white society.

Is my feeling that there may be a trade off between the artistry of these novels and their social range a sign of my own limitations as a reader? This may be the case. For reading the novels reveals much complexity. The novels deal with a very intensely concentrated and self-revealing personal psychology in dialogue with its readers. But there is also the reportage of talk from self-talk to interactions in groups from couples and families upwards to strangers met either on purpose or not so. Beyond this intense preoccupation with the socially successful bourgeois individual is an interest in how that preoccupation mediates social distinctions and differentiations as a mark of how such subjective entities are socially formed. For the characters of Oh William! are obsessed with their origins and what these origins mean in terms of their own being, especially in comparison with others. Indeed Laura Miller in her review for The Guardian claims that the book is portentously about class as well as relationships and self-making:

This is also a novel about class, an American taboo, the denial of which contributes to making Strout’s characters unknowable to each other. Lucy, who grew up in a house that was without a television or indoor plumbing, freaked out when William’s mother took the family to a resort in the Cayman Islands. “I had no idea – no idea at all – what to do: how to use the hotel key, what to wear to the pool, how to sit by the pool”.[4]

A key comparison that undergoes variation in what we know of both persons and their relationship is that between Catherine, the mother of Lucy’s first husband (the eponymous William) and Lucy. Very early on we are introduced to the fact that Catherine had a good social standing, her first husband having been a successful farmer and politician, her second (William’s biological father) a civil engineer. A lot of weight is carried by the simple sentence: ‘So Catherine was not poor’. Her home strikes Lucy as ‘surprisingly’ elegant, for one thing. This fact sparks the comparison with Lucy herself, such that we understand early that Catherine amounts to a rather important index of how Lucy measures her own social worth: it uses the ‘American class system’, despite the fact that she ‘never fully understood’ it, to hone in on Catherine and herself as an exemplum. Catherine, Lucy muses, ‘had ended up rather high on the social scale’ whilst she ‘came from the very bottom’ of that system and has ‘never really gotten over it, my beginning, the poverty, I guess is what I mean’.[5]

So deep is class registered that it strikes viscerally and sensuously – as a smell for instance. For ‘Catherine always smelled good’, whilst Lucy compulsively buys perfume to defeat the obsessive idea, analysed by her psychiatrist as a belief that she stinks. The stink is that of lower class poverty – more a psychological than an objectively defined fact, internalised from children in the playground saying to her in her early days: “Your family stinks.”[6] Her self-learning by the end of the novel spins around her revaluation of the comparison of self and Catherine. Catherine used, Lucy tells us to introduce her to her friends with the sentence: “Lucy comes from nothing”.[7] Yet what William and she learn later is that Catherine may have used this bold contrast in her own favour in order to disguise the fact, as Lois (William’s half-sister, Lois, says) that she “came from less than nothing. She came from trash”.[8]

The fact of ‘coming from trash’ is registered by an almost obsessive concern with the size of the house from which Catherine originated. For if Lucy came from ‘a very small house’ William and she find Catherine’s birth home ‘the tiniest house I think I have ever seen’.[9] But that obsession reflects in truth on her own with the negative associations of her own class origins and is not as much reductive as the class-obsessed Lois thinks it to be; stuck in her small provincial world where white trash remains white trash. At the bottom of the mystery is that this comparison is even perhaps more in awe of the fact that Catherine maintained her sense of self-worth despite all this and embraced any transformation, including that given by expensive perfumes which in later life she could buy. At university Lucy’s English professor’s wife confessed that from the first meeting with Lucy she had thought: “That girl has absolutely no sense of her self-worth”.[10] Lucy, even after realising Catherine’s origins were more like her own, will keep talking about her own ‘tiny’ house and associating her own origin with her belief in her ‘stench’; ‘as though I had a smell’ people ‘did not care for’.[11]

So why is the self-comparison with Catherine important? I would answer this question in terms of its effect on William, Catherine’s son, and its reflection on his role in the historic and continuing development in Lucy’s self-conception. For what William inherits from Catherine is an exaggerated sense of the importance of social origins in the making of persons. After the discovery of Catherine’s tiny house Lucy believes that the true reason William chose her as his wife was because Lucy was the ‘same sort of woman’ as his mother, Catherine. William insists that this was not the case and, unconscious anyway of Catherine’s earlier ‘awful poverty’, he says that, in coming to know the lowliness of Lucy’s home and parents he had ‘almost died at what [Lucy] came from’. Except that Lucy had, in some way transcended that real origin with some self-made ‘joy’ and ‘exuberance’ in life.[12] Lucy’s response to these statements is muted but I think most readers will feel that William still has not realised that he is still describing his mother, who too had used individual spirit of some kind, as well as expensive clothing and perfume, to ‘transcend’ her origins. In truth this conversation is the beginning of the most important change in the novel – where both Lucy and he realise the illusions on which William’s sense of self is based. From this conversation onwards, as realisation sinks in, ‘William began to close down’, and his outer spirit is left high and dry as everything ‘behind’ his handsome face ‘retreats’, as we ‘see him going away’.[13]

Oh William! is a novel that searches the psyche that in other ways limits its scope, a psyche that has begun to admit its own limitations. And it starts with the psyche of William. This is the reason I believe for the repeated exclamation titling the novel, ‘Oh William’.[14] This exclamation seems to gain the weight of the recognition of a particularly human frailty that is both disguised and defined by a failure to empathise with the other, illusory beliefs about one’s capacity for love and, sometimes, lies. For instance, Lucy has to educate him (somewhat hopelessly) about what is and what is not empathetic in speaking to their daughter, Chrissy, following her miscarriage.[15] This is said too in one of the most hidden of the ‘Oh William’ comments. That comment is embedded amid a sentence that performs a retrospective about how Lucy thought about William, based on his lack of any genuine interest even in a child of his current marriage with Estelle (Lucy’s successor); a retrospective that will inform her future evaluations of him too: ‘And I was thinking, Oh William, let’s make this quick, you are such a baby. Dear God, I was thinking, you are such a child’.[16] And what makes Lucy most despondent is that William is unable to face up to realities, such as about his mother’s real past as distinct from that illusory one in which he wanted to believe. Thus, when William pursues his mother’s family history, facts he does not want to know such as the existence of a half-sister, get suppressed – under lies if they are necessary and even when, to Lucy, ‘when we hung up, I realized that William was lying’.[17]

Once he finds his half-sister, Lois Bubar, he wishes ‘she never existed’, as if wishes could eradicate a person facing one with thoughts or feelings we wish not to have; as Freud insisted children and adults in dream-states also sometimes ‘believe’. And, most of all, William fears rejection and has, Lucy thinks, an almost paranoid belief that he invites such a fate to himself, perhaps forestalling his certainty that he is unlovable:

And his face, that slight bafflement that crosses it sometimes. I thought: here is one more woman – in his mind – who has rejected him. And I thought once more of the nursery school teacher who had never picked him up again after having made him feel so special. …

For people are not always as they would like to think of themselves as being, and if William is a perfect example of this, he is also a mirror of the fact that this may apply to Lucy herself. A favourite passage of mine is when Lucy recalls her conversation with William about whether people are more ‘mean’ than they like to think themselves. Here the word ‘mean’ is packed with ambiguous meaning – suggesting people are not only more selfish than they like to think but also less that they like to think of themselves – ‘mean’ in the sense of sparse or inadequate in volume or shape – and perhaps too more intentional in their actions, even ones that hurt others, than they like to think, so that at some level, they really ‘mean’ what they are doing.

… I said, “And you don’t choose to be mean, William.”

“I kind of don’t,” he answered.

And I said, “I know that!” Then I added, “I’m really mean in my head, …

William threw his hand up and said, “Lucy, everyone is mean in their head. Jesus!”

“They are?” I asked.

He half laughed, but it was a pleasant laugh. “Yes, Lucy, people are mean in their heads. Their private thoughts. Are frequently mean. I thought you knew that, you’re the writer. Jesus Christ. Lucy”.[18]

Are we all mean: smaller in significance than we think, less moral and more selfish than we admit, and perhaps more intent on rejecting others than facing rejection ourselves? I think this a key theme of the book and explains why realising William’s lack of genuine self-knowledge might also reveal that of others, even our selves. Hence the words for it cited in the title: ‘But when I think Oh William!, don’t I mean Oh Lucy too? / Don’t I mean Oh Everyone, Oh dear Everybody in this whole wide world, we do not know anybody, not even ourselves!’[19] Sheena Joughin calls these words, in her review in Literary Review, ‘tender, inclusive and oddly reassuring’, for they generalise William’s deficiencies including his blindness to them.[20]

And the generalisation is important because it is clear that Lucy learns too more about her genuine meanness even to her own daughter, a meanness that prefers not to really listen to others than the revolutions of her own issues in her head (‘I was self absorbed’); as in this incident:

And Becka burst out, “Mom! I am trying to tell you something and all you can do is talk about your editor!” And she wept then.

Oddly, that moment clarified something to me that day … It clarified to me for a moment who I really was: I was someone who did that. And I never forgot it.[21]

And it is ‘William’s observation that I was self-absorbed’ she reflects upon, though she ‘was really uncomfortable thinking about it’ and preferred to see such a trait as that of others she knows not herself, the novel stops her short and forces her to reflect herself with more honesty.[22] And there is no excuse for not reflecting on oneself, even class – for Lucy uses the fact that her tiny home had only one mirror to do just that, interestingly – as Laura Miller points out in her review.[23] What this also shows is the kinds of work the word ‘reflect’ is asked to play in this novel of cunning word-play. It is a word that takes us back to the theme of self-worth and the responsibilities that people have for owning their self-projections in interactions with others – whether inside families, in marriages or in other interactions, such (as we will see) interactions writers have with their readers. As Lucy brilliantly puts in a sentence that is also a paragraph in its own right: ‘I am not invisible no matter how deeply I feel that I am’.[24] And there is no excuse for pretending to being unseen or not in existence for our agency still acts on others, whoever we are; either significant and weighty persons or mean and poor. This is the passage I earlier referred to as pointed out by Laura Miller, where Lucy talks of her earlier poverty:

I feel invisible, is what I mean. But I mean it in the deepest way. It is very hard to explain. And I cannot explain it except to say – oh, I don’t know what to say! Truly, it is as if I do not exist, I guess is the closest thing I can say. I mean I do not exist in the world. It could be as simple as the fact that we had no mirrors in our house when i was growing up except for a very small one high above the bathroom sink. …[25]

There is something special going on here, wherein a writer shows that we cannot escape existence, visibility or meaning, however hard we try to exempt ourselves from such agency and its effect on others. Nothing offers a way to escape ourselves precisely because no one is truly ‘invisible no matter how deeply’ they ‘feel’ that they are. For this theme reflects at its deepest level on the techniques of novel-writing. It takes little reflection to see that Lucy’s apparent diffidence about herself is actually a demonstration that no writer truly is ‘invisible’, even when the disguise themselves (as Strout may be thought to disguise herself under Lucy BarTon’s differences from her).

So cunningly interwoven is this theme is that it hides in plain sight. For Lucy Barton is not only a ‘novelist’, she makes her novel out of the interplay of the fictive and the true that is at the basis of all novel-writing. As a novelist she also teaches novel-writing, she tells us, including about the nature of an author’s authority, comparing it to the motivations lying behind that behaviour we call falling in love. In both cases authority amounts to ‘believing that in the presence of this person we are safe’.

When I taught writing – which I did for many years – i talked about authority. I told the students that what was most important was the authority they went to the page with.

…

This authority was why I had fallen in love with William. We crave authority. We do. No matter what anyone says, we crave that sense of authority. Of believing that in the presence of this person we are safe’.[26]

That authors are defined by authority is an obviousness but its associations are rich, for here authority is implicitly defined as a ‘presence’ that makes the receivers of its presence ‘feel safe’, as a good husband does, or an adequate parent. And feeling safe is constantly evoked in this novel in the latter terms as both William and Lucy contemplate their own parents, spouses and their own relationship to their children. By the end of the novel, Lucy contemplates the fact that William ‘has lost his authority’.[27] But author’s ought to have authority because their presence makes a reader feel safe. Yet Lucy is constantly asserting her invisibility whilst demonstrating that she is NOT invisible but merely lacks authority with some things readers trust to authors. Of course Lucy is a fictional author and actually constructed by one whose authority stands behind this novelist-cum-character-in-a-novel, Elizabeth Strout, whose reserve is as legendary as her brilliance and control of her novelist’s craft. We get to know Lucy too well whilst feeling we know her not at all. Note how Jonathan Myerson in his Guardian review puts an effect of this novel:

And without the usual kind of narrative dilemma waiting to be satisfied, the intense pleasure of Strout’s writing becomes the simple joy of learning more while – always – understanding less. “We are all mysterious, is what I mean,” says Lucy towards the close of this novel, leaving us already hungry for the next one.[28]

This is beautifully precise about the effect of the novel, whilst failing to look at the point that is so obvious in his description that Strout’s writing is not the same thing as what Lucy, her narrator-novelist says within it. For I believe that some of the ‘mystery’ and obfuscation of human learning is an effect of Lucy’s character that Strout makes ironically available to us. It is Lucy who keeps attempting not to be seen whilst paradoxically being seen the more. She talks to the reader as if they were co-present with her, showing that she is in control of what we are told as well as what we are not told, whilst making her presence problematic in terms of how she is mediating the story thorough her own pre-occupations.

Strout even makes some of the characters ‘readers’. William clearly is and more than once refers Lucy to her authority as a ‘writer’, whilst Lucy pretends ignorance of some, even, of the most obvious human psychological responses. She asks readers – almost pleads as if she had no authority – ‘Please try and understand this: / …’.[29] She plays at descriptions while draining them of the authority of knowing exactly what to say about her subject, as in this instance, where readers might reasonably ask why she needs to say what ‘she needs to say’ or otherwise – but just say it with authority :

Except I do need to say this; My husband’s name was David Abramson and he was – oh, how can I tell you what he was? He was him! We were – we really were – kind of made for each other, except that seems a terrifically trite thing to say but – Oh, I cannot say any more right now. (author’s italics)[30]

Every part of this lacks authority of statement which rarely uses forms like ‘kind of’ as a qualifier or insists on meaning through insistence or italics. She keeps reminding us of earlier books and repeating things from them or refusing to do so. Yet she sometimes neglects the fact that her readers have belief that they access her thoughts by reading here. For instance I have already cited the moment where she cites Catherine telling her friends that ‘Lucy comes from nothing’.[31] A wonderful effect in the novel is that when Lucy eventually meets William’s half-sister, Lois, that lady knows (or assumes she does) Lucy already because she is one of her readers. When Lucy meets her, Lois cites that moment, because as Lucy told us in that earlier moment, ‘I wrote about that in a previous book’.[32]Later in the novel, Lois quotes Catherine saying that Lucy came ‘from nothing’ precisely quoting that earlier book. Lucy lacks ‘authority’ most when she says to Lois:

…”How – how do you know that/ About my mother-in-law, that she would say that to people?”

Lois said simply, “You wrote it.”

“I wrote it?” I said.

“In your book – your memoir.” Lois pointed her finger to a bookshelf that was over to my right. Then she got up from her chair and walked over and brought out my memoir – it was a hardback – and as I watched her do this I saw that she had all my books lined up there; I was amazed.[33]

Here the author has forgotten she is an author and that anybody can read her and claim to understand her by her authority. It is a moment of pure transparency about one’s own brilliance as a novelist on Strout’s part. But it also places Lucy in a moment of self-learning yet again, for if anything this is a novel about how we use each other either to learn or refuse to learn, to grow and grow up – or the reverse of each.

It is a lot to write upon a strip of ivory (two inches wide). Should it win the Booker? Well it deserves it. I still feel though that Strout’s reward should be in lasting acclaim and of that she already has much as well as prizes. And it will last as long as reading is made available and not just through universities.

All the best

Steve

[1]Elizabeth Strout (2021: 237) Oh William!, New York & London, Viking, Penguin Books

[2] See https://general-southerner.blogspot.com/2010/02/little-bittwo-inches-wideof-ivory-on.html

[3] See ibid: 199. For words like ‘tiny’ and ‘small’ to describe origins and the link to ‘Nothing’ see ibid: 177f., 196, 211, & 222, for instance.

[4] Laura Miller (2021) ‘Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout review – the return of Lucy Barton’ in The Guardian [Wed 20 Oct 2021 07.30 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/20/oh-william-by-elizabeth-strout-review-the-return-of-lucy-barton

[5] Strout op.cit: 40

[6] Ibid: 44f.

[7] Ibid: 40

[8] Ibid: 178

[9] Ibid: 196

[10] Ibid: 218

[11] Ibid: 222

[12] Ibid; 197f.

[13] Ibid: 199

[14] For repetitions I noted see ibid: 99, 134, 161, 203 & 237.

[15] Ibid: 43f.

[16] Ibid: 49

[17] Ibid: 61

[18] Ibid: 155f.

[19] ibid: 237

[20] Sheena Joughin (2021) ‘Remembrance of Husbands Past’ In Literary Review (Wednesday 17th August, 2022) Available in: https://literaryreview.co.uk/remembrance-of-husbands-past

[21] Strout op.cit: 151

[22] Ibid: 161

[23] Laura Miller, op.cit.

[24] Strout op.cit: 149

[25] Ibid: 62f.

[26] Ibid: 132

[27] Ibid: 233

[28] Jonathan Myerson (2021) ‘Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout review – Lucy Barton’s return brings intense pleasures’ in The Observer (Sun 24 Oct 2021 09.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/24/oh-william-by-elizabeth-strout-review-lucy-bartons-return-brings-intense-pleasures

[29] Strout op.cit: 62

[30] Ibid: 33

[31] Ibid: 40

[32] Ibid: 40

[33] Ibid: 177f.

One thought on “‘But when I think Oh William!, don’t I mean Oh Lucy too? / Don’t I mean Oh Everyone, Oh dear Everybody in this whole wide world, we do not know anybody, not even ourselves!’ This blog is about Elizabeth Strout (2021) ‘Oh William!’: BOOKER SHORTLIST REVIEW.”