‘You want to ask the universe what everyone else wants to ask the universe. Why are we born, why do we die, why anything has to be. And all the universe has to say in reply is: I don’t know, arsehole, stop asking. The Afterlife is as confusing as the Before Death, the In Between is as arbitrary as the Down There. So we make up stories because we’re afraid of the dark’.[1] This blog contains my personal views of Shehan Karunatilaka’s (2022) The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, London Sort Of Books. This blog CONTAINS SPOILERS so do not read if you do not like that: BOOKER REFLECTIONS LONGLISTLIST 2022. For your info: @ShehanKaru

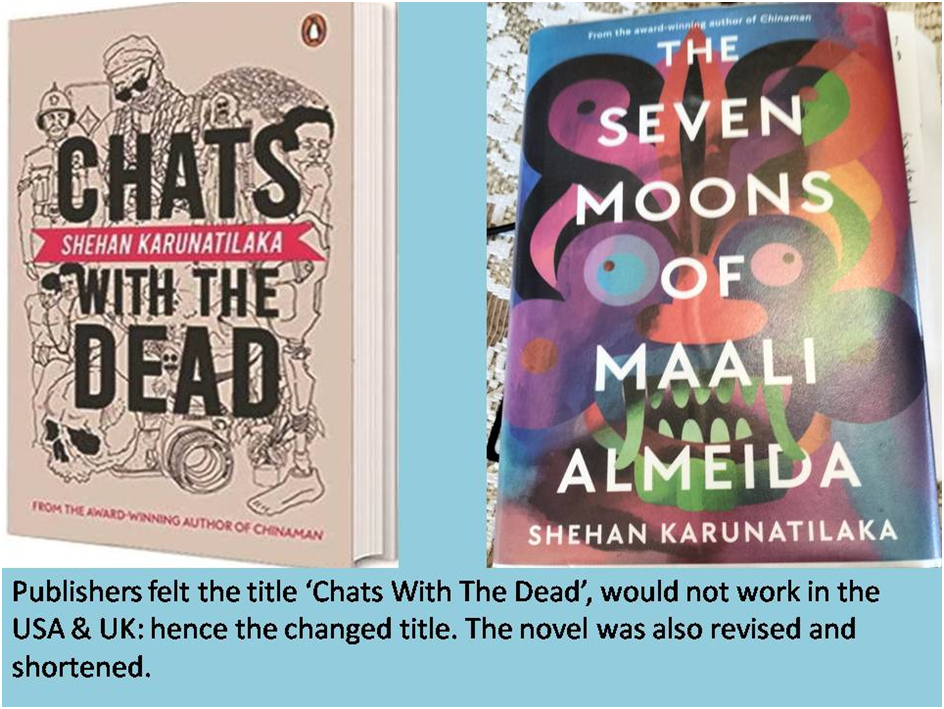

This is a novel that already has a history in the public realm in non-Western markets for books written in English under the title Chats With The Dead. It has only very recently been published with the new title The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, in the UK. The UK publication occurred fortuitously just after the announcement of that format of the novel’s inclusion in the Booker longlist. Hence, there are few UK reviews as yet, although one appeared in The Guardian online on the 9th August by Tomiwa Owolade, a freelance review writer. This review, however, with an exception I will look at later, does capture the story well including its ‘absurdities’ from a realist perspective, and uses honoured names from long and varied international traditions that have authored works unique even in their own cultures to suggests how our present novel might be categorised and placed in those traditions:

The obvious literary comparisons are with the magical realism Salman Rushdie and Gabriel García Márquez. But the novel also recalls the mordant wit and surrealism of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls or Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. The scenarios are often absurd – dead bodies bicker with each other – but executed with a humour and pathos that ground the reader. Beneath the literary flourishes is a true and terrifying reality: the carnage of Sri Lanka’s civil wars. Karunatilaka has done artistic justice to a terrible period in his country’s history.[2]

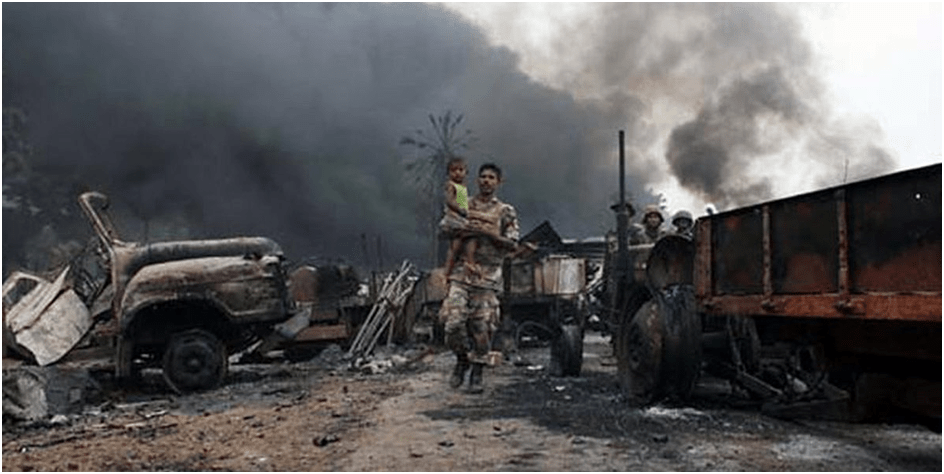

The point of such comparisons are necessarily limited and appear only tentative even in this review. However, in each case the queering of the norms of ‘realist’ (or any singular genre or literary mode) enables each novelist to take on large socio-cultural political themes appropriate to a particular time and place. Hence it is possible that the names are not invoked merely as exempla of the kind of ‘literary flourishes’ found in this novel. For each of the novelists attempt to come to terms with the politics of a nation (often more than one nation) so bathed in tragedy that its recourse to literary expression must be in grotesque black comedy that ‘magic realism’ as a name barely acknowledges.

There are a range of literary effects achieved in Karunatilaka’s new book, that range from the philosophical pastiche, as in the citation from it in my blog’s title, to the surreal, the fantastical and the morbid stuff of horror comics. Roshan Ali, another commentator, finds in it (correctly I think, especially with regard to the pace of its denouement) the tension of a popular ‘whodunnit’, wherein the main character ‘solves his own murder’.[3] Everyone acknowledge the skilful and urbane wit of the prose and most the fact that some sections, such as the transportations of the varied ghosts and ghouls across real time and space on the roof of a tuk-tuk, that are deeply comic (sometimes urbane and sometimes purely farcical as in a Laurel and Hardy sketch).

However, Gazala Anver, the deputy editor of one Sri Lankan online review publications, roarmedia, insists that some of this horror, with its reference to common Sri Lankan folklore and mythology, can limit the novel’s interests to its ‘local’ Sri Lankan context . This stress on the ‘local’ though seems somewhat stretched to me since the folklore and mythology addressed often has resonance across South East Asia, such as that of the Mahakali, for instance, which is traditionally associated in Tantric and other sources with time and death. This association explains why, in this novel, she performs this function only in the timed duration (seven moons) allowed for ghosts to inhabit the ‘In-Between’ with its direct and physical partial-connection to their lost lives before their whole lives are absorbed into the Light of timeless oblivion. It explains too her vast hunger and the heads of the eaten ghosts who speak so wittily, sometimes (but always in a riddling way) from within her ever expanding flesh.

For Anver though these associations are not her point. She sees these features as just another part of the novel’s immersion in Sri Lankan ‘localism’; indeed she identifies his method in both of his current novels as hyperlocal. In the section from her review below she expands the term ‘hyperlocal’. Whilst there are frequent attempts to save the book from being seen as of somewhat limited international literary significance because of this trait, she does not quite succeed in my opinion. However, decide for yourself:

The mythology is familiarly Sri Lankan but it does not feel contrived, touristy or orientalist: rather, Karunatilaka thoroughly workshops this world to the point where it feels lived in, even real. … / … there is no attempt to mark out “local” words and make them more palatable for a global audience, nor does the book attempt to tame and cage the strange beast that is Sri Lankan English. / Its hyperlocality works two ways; on one hand, there is a tendency to lean on stock Sri Lankanisms, which can get exceedingly annoying after a while. There are only so many references to Sri Lankanisms such as elephants and King Buvenekabahu III before the similes and analogies get tiresome and feel a tad overwrought. On the other hand, the book reads like a map that requires a certain intimacy with all things Sri Lankan to be fully appreciated and understood. Anyone standing outside may get lost in the hair-raising tuk tuk ride (and this is my attempt at a ‘Sri Lankan’ analogy) that the book is. There is little to no reductive attempt at explaining life in Mother Lanka, nor an attempt at boiling this life down into a concentrated syrup of orientalist clichés.[4]

But both of the South East Asian reviews I cite in this blog see something in the novel missed in the Guardian reviewer’s take: it’s beauty as a complex and nuanced story of entangled and multiple human love relationships. Anver perhaps attempts to see the new interest in human love story as somewhat distinct from its other themes and as an advance in the writer’s literary significance away from the ‘hyperlocal’ and obviously political :

There is much you can say about sexuality, politics, and war but I would like to argue that neither are the crutch (sic.) for at the core are personal relationships, which is where Karunatilaka’s strength and evolution as a writer show’.[5]

Owolade misses all of this, even in telling the story. However, I prefer that blindness to this tenderness in the novel, which I love too, to the attempt by Anver to depoliticise the theme of romantic, sexual and comradely love that spreads across gender, sex, politics, race and cultures in this incredible novel of queer loving. Anver focuses her appreciation of the novel’s ability to render tenderness in developments in human sexuality through the characters of Jaki and DD. Jaki is a woman who masks Maali Almeida’s (hereafter Maali) sexual preference for relationships of differing intensities with multiple men by pretending to be his female partner. DD (Dilan Dharmendran in full but usually referred to by those initials except by his norm-preserving father) is a young man who fails to see his father’s corruption as a politician but who is led to radical, leftist sexual and other politics by the end of the novel, and to a relationship with a man outside the ‘closet’. I feel personally that the emphasis on the normative (hetero- and homonormative) to describe the two characters here as part of ‘an unexpected and heart-rending story of love in all its iterations and complexity’ is reductive. It misses the point that some of the nuance and some of the perplexity of loving in the novel s the result of the pursuit of that which the normative finds queer – women who commit to gay men and to women (or both), men whose questioning sexuality runs through their development and, most important, those who must have multiple variegated sexual relationships and the lies that involves and that is, perhaps, essential to them as persons AND their coming out. It also misses the rich reference also to queer historical concepts – notably the meaning of the ‘closet’ (but more on that later). This is what I refer to understand in Roshan Ali’s liking for the strength of the novel’s ‘social realism’.[6]

Anver chooses not to include in her consideration of love Maali himself and his self-professed and oft explored identity, which should be, the second-person narrator says on the man’s’ ‘business card’ (if he had one which he doesn’t): ‘Photographer. Gambler. Slut’.[7] The pursuit of multiplicity in relationships is central to Maali Almeida, despite the tender revelations of his genuinely deep love (of different kinds) to Jaki and DD. But full commitment (in the sense of monogamous loyalty) to either is not seen as a goal, even if DD and Maali were to ‘go to San Francisco and make money and love and let this shit country burn to the ground’.[8] The ‘shit country’ is Sri Lanka and Maali resists DD with irony here not because he does not love him but because his love is not seen as exclusive of multiple other partners, including Jaki and the lost soldiers and civilians, Tamils and Sinhalese, he confronts in the bunkers of hopeless war fronts and whose corpses he photographs. Indeed his final retrospective exhibition lumps together in one show all these aspects of his multiple loving, even those which revolt DD – such as the old (to whom the young wrongly pay little attention the narrator says at one point)[9] and the ‘ugly’. Amongst the photographs of corpses in the public exhibition, and loving ‘Perfect Ten’ ones of DD, are, to Maali’s momentary horror, a boy laughingly called Lord Byron ‘with long hair and oily face’, who ‘was picked up while jacking on a bus and snapped with shirt off in a public toilet’. Boys with a ‘certain look in their faces’ (a look which a more restrained and cultured DD never lets Maali see even when they have sex): that of a ‘wild-eyed, dishevelled post-coital comedown’.[11]

For a queer perspective cannot rescue romantic love ideologies from their contradictions. Norms in paradigms of love in truth are merely things which cover up the ‘abnormal’ and hidden and silenced realities (in both politics and sex). This is what Anver fails to see. There is no great novelist in development here if we only see it manifest in DD and Jaki finding non-closeted but norm-ridden relationships as its end. This is a great novel, in my opinion, because it attempts to question what we call ‘high’ and ‘low’, ‘beautiful’ and ‘ugly’ categories in art. It insists that such binaries of judgement are as false to reality as more famous ones, such as those of sex/gender. The non-binary In-Between in this novel is the place that Maali will learn is where he will ‘need to be’.[12] It is a novel about rescuing lost voices from the various means of the suppression, even the transgender ghost. They are asked:

“Why haven’t you gone into The Light?”

“I’ve been In Between all my life,’ said the she who was a he. “Maybe this is where I belong.”[13]

Refusing to be a ‘worthless soul’ as Dr Ranee calls them from her ambiguous position on the portal to The Light, is to recognise the beauty and right to exist of those condemned as ugly, sick or bestial by conventional norms. Maali in the In-Between finds that animal – human binaries are questioned as much as any other. Maali too will learn that it is the In-Between where he, at least, must stay, even whilst Jaki and DD find other homonormative possibilities of relationship. This is because his very soul commits to the right to political expression of the disempowered, of which animals are the most disempoered. The narrator summarises the situation thus following a conversation between Maali and a polecat:

There are good reasons humans can’t converse with animals, except after death. Because animals wouldn’t stop complaining. And that would make them harder to slaughter. The same may be said of dissidents and insurgents and separatists and photographers of war. The less they are heard, the easier they are forgotten.[14]

Whether such a subtle exploration and exposition of the queer and ‘In-Between’ may make a Booker winner is not clear but something in me hopes it does. However, it will need better readers than the reviews I have seen. For these are too keen to find its faults as a novel to see what is actually there in the novel. This novel deals with realities that even some LGBTQIA+ commentators find it difficult to discuss when in pursuit of the myth of positive images alone. In this novel, references to AIDS appears as a sign of a suppressed subject that touches on the negatives of a silenced queer life. AIDS is thing that the politician Stanley Dharmendran’s uses to define his fears for his gay son, DD, and is a subject even Maali disposes of quickly in order to have sex with DD, using a condom (which DD in his naivety fears signals having AIDS).[15] Another topic suppressed but necessary to the consideration of real queer lives in an oppressive society is suicide – those of queer people and others who refuse. or are perceived as resistant to, norms. Considering Sri Lanka’ ‘prolific suicide rate’ amongst ghostly persons who had completed suicides, and play at for fun now in the In-Between, Maali discerns: ‘the jilted lovers, the bankrupt farmers, the refugees of botched revolutions, the casualties of rape, the students who failed the grade, and more than a few closeted homos’.[16]

This last quotation is one of the many references to the ‘closet’ in this novel. My favourite instance is in a very great sentence I noticed early in the novel and which made me think, for the first time, that this novel was intent on exploring the many ways in which secrets and a lack of openness had agency in driving misery and enforcing it. That, after all, is the tragedy of non-human animals: their lives are not heard as voices as we have seen above. At this point in the novel, momentarily Maali cannot move for ‘invisible walls barricade you and all winds have ceased’. He feels ‘encased in padded glass, held by arms he cannot see’. It is like the Hell of Coleridge’s The Ancient Mariner. Here appears a sample of the tragi-comic lightness of this novel of which no queer person would miss the significance:

You were never claustrophobic despite all that time spent in bunkers and narrow beds and lifelong closets. But, like any reasonable person, you’d like the option of running away, especially when there is plenty to run from.[17]

The option of running away has many versions of which suicide may seem but is not one, though it is often the only ‘option’ apparent in distress and pain. DD wants to run away to San Francisco but, in the end, staying in the oppressions of Sri Lanka may be the author’s choice, for where do we find true openness and an ‘Honest Politician’, except for that there was one such ‘mythical creature’ in Sri Lanka once: ‘Don Wijeratne Joseph Michael Bandara who ‘worked for the downtrodden and the forgotten, argued for Tamil workers, Muslim traders, Burgher drivers and Chetty chefs’.[18] The woes of Sri Lanka we found are moreover upheld by Dishonest Politicians in countries to which Sri Lankans flee, politicians like Margaret Thatcher.[19]

However, ‘homophobic abuse’ also comes from other members of the In-Between unless one voices resistance.[20] The issue is not having an identity as a gay man or lesbian but accepting the truths of sex and power and working with them, articulating your marginalised positions as much as possible, even by transgressive photographs, to avoid the disappearance that happens to things with ‘big tongues, thick hides and small brains’ when ‘faced with bullies’: that state of being in reality a set of behaviours ‘hundreds of thousands of years old and plodding to extinction’.

It is not a liberationist philosophy this but of finding one’s ‘negatives’ (the pun runs through a plot where everyone is looking for Maali’s ‘negatives’ (photographic or otherwise)) and finding them both meaningful and beautiful because open to change once exposed to light. In this novel political movements, institutional or otherwise, aren’t keen on exposing truths in photographs except for self-interest. One rather amusing parable of this is in the discussions of the penis (named ‘eggplants’ in the parable to hide their reality and emphasise the humour) mixed with discussion of Maali’s photographs by DD and Maali:

DD called it the ugliest thing in the universe and you told him there was plenty of ugly in the world and this wouldn’t even make the top ten. The box under the bed contained five envelopes and each of the contained its own share of ugly. … /

DD said he’d only seen three eggplants in his life: your, his father’s and his own.

“Such a privileged existence,” you said. “… Most look like chicken necks, some like mushrooms, a few like baby’s fists’.

“You’ve seen plenty, no?” asked DD, a question more loaded than the armoured car manned by children that carried you once in Kilinochchi.

“A few,” you said. “They were all beautiful.”

“I bet you’d kiss anything,” said DD. “Anything that moves. Anything that won’t”.

…

“We all like eggplant, what’s the issue?”

“I only like yours.”

…

You tell him the pecker is proof that man has no free will. …

“We do not control what sends blood to our pricks. …[21]

This smutty conversation ( I do not say this in distaste) is harmonious with the philosophical discussions of ‘free will’ and the attempt to find meaning in the world by controlling it through erasure of that which makes us human – that to which we rarely admit. The novel’s politics is anti-institutional, even when the institutions are like those of the opposed racially purposed armies of the then Sri Lanka like the Tigers, each of which claims to be liberating or freeing something by its own will. The issue is being able to see that what is and not ugly, to a limited point of view, is no excuse for its social exclusion. Of course this a confusing and contradictory ‘theory’, if theory it is; any more than Maali’s ‘grand theories of the penis’ are theories.[22] It will not provide us with a blue print for our philosophy, ethics, literature or politics but it will stop us from speaking over those we fail to credit with value: things we call beauty, purity (of race for instance) or sexual mores.

This is a wonderful novel. Will that be noticed?

All the best

Steve

[1]Shehan Karunatilaka (2022: 196f.) The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, London Sort Of Books

[2] Tomiwa Owolade (2022)’ life after death in Sri Lanka’ in The Guardian (Online) [Tue 9 Aug 2022 10.00 BST]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/aug/09/the-seven-moons-of-maali-almeida-by-shehan-karunatilaka-review-life-after-death-in-sri-lanka

[3] Roshan Ali (2020) ‘Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka returns with a crackling whodunit a decade after his debut’ in Indian Express (online) [February 23, 2020 9:03:23 am] available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/shehan-karunatilaka-chats-with-the-dead-dark-places-6281945/

[4] Gazala Anver (2020) ‘The Hyperlocal Beast: Shehan Karunatilaka’s Chats With The Dead’ in roarmedia (online). (20 Oct 2020) Available at: https://roar.media/english/life/literature/hyperlocal-beast-shehan-karunatilaka-chats-with-dead

[5] Ibid.

[6] Roshan Ali op. cit.

[7] Shehan Karunatilaka (2022) op.cit: 1

[8] Ibid: 234

[9] Ibid; 305

[10] Ibid: 302

[11] Ibid: 306

[12] Ibid: 368f.

[13] Ibid: 285

[14] Ibid: 342

[15] Ibid: 376

[16] Ibid: 286 My italics

[17] Ibid: 140

[18] Ibid: 148

[19] Ibid: 188

[20] Ibid: 243

[21] Ibid; 30f.

[22] Ibid: 31

One thought on “BOOKER SHORTLIST ‘You want to ask the universe what everyone else wants to ask the universe. Why are we born, why do we die, why anything has to be. And all the universe has to say in reply is: I don’t know, arsehole, stop asking. … So we make up stories because we’re afraid of the dark’. This blog contains my personal views of Shehan Karunatilaka’s (2022) ‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ @ShehanKaru info.”