BOOKER REFLECTIONS LONGLIST 2022: ‘…, it seemed as if her anatomical nightmares had begun to bleed into the days’.[1] This blog contains my personal views of Maddie Mortimer’s (2022) Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies, London, Picador. This blog CONTAINS SPOILERS so do not read if you do not like that.

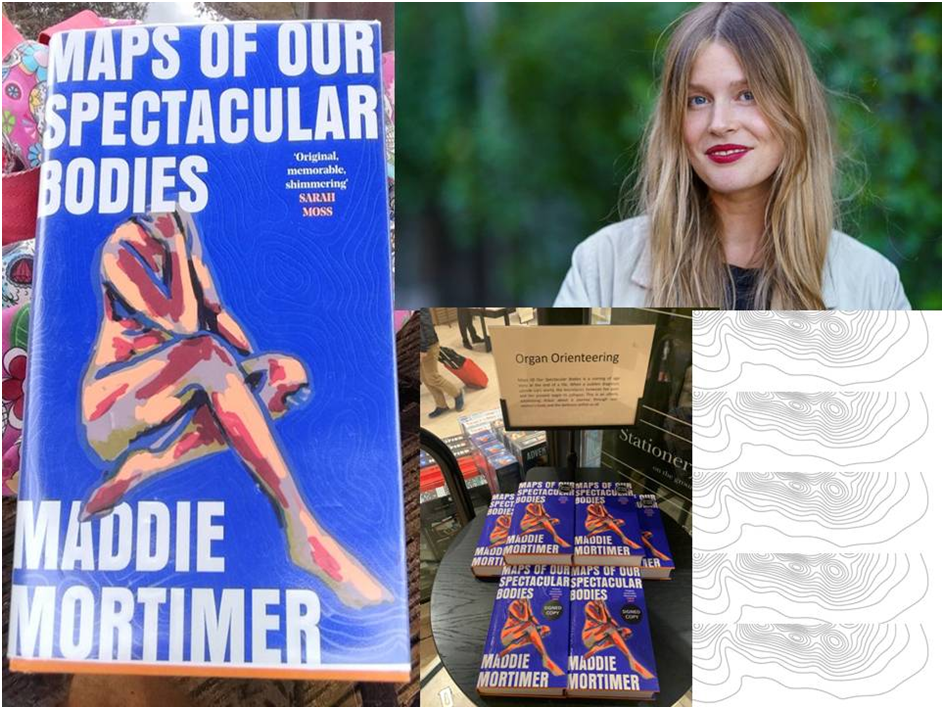

Figure 1:

This book took me by storm It’s a storm of the kind described in the book by writing that imagines what it is, not just what it feels but what it mean to one who experiences it, to have an epileptic seizure resulting from a brain tumour. It is imagined such that which what is outside and inside the brain, mind, body, perception of community or whatever noun, noun-phrase or set of nouns you want to wrangle with is terribly mixed up with each other, even around the use of the verb ‘seizes’ to evoke what in two pages will be translated as: You had a bad seizure. The ambulance came’.[2]

And then the world seizes; the fields and Mr Birch’s tree and the outline of the boxy vicarage and the church turret are all flung upside-down in the back of her sockets, the electrics mad, nerves flaying.[3]

As a verb ‘seizes’ is always transitive, describing the action of a subject on an object, person or persons, hence the first phrase above begs the question of ‘what’ or ‘whom’ is being seized. We can assume all the nouns that follow the semi-colon in this sentence are that which is ‘seized’ by the world, but the logic of the sentence, and indeed the objects taken as a picture of a landscape in a remembered world suggest the verb is straining to be intransitive . If so it suggests ‘the world’ may not only seize things but be seized by itself (thus becoming a verbal equivalent of the medical term ‘seizure’ (a noun) conveying a meaning like ‘the world had a seizure’. And what is seized are the details of the ‘parish’, vicarage and surrounding landscape in which Lia is born and in which Matthew and Lia have the sexual union leading to the conception of Iris. Iris will only learn of her biological father’s real identity at her mother’s death. All the elements that are shaken up and violently displaced in this picture recur through the novel: Farmer Birch and his tree and fields where the couple court and have sex, the ‘boxy’ vicarage where the seduction and final conception act occurs – all now become the frayed stuff of neurological vision – an inside-outside world.[4]

Whilst all these effects apply I think; their importance is that phenomena proper to bodies and their internal states become applied to the external world, even though that world may still be an internal image captured by the retinal nerves. What is ‘outside the body therefore plays against what is deep ‘in the back of her sockets’ of the body. These things must have been actively seized however in order to be ‘flung upside-down’. That phrase ‘flung upside-down’ could describe a violent effect on reality or an illusion, although strictly speaking such inversions occur even in the normal process perception at the eye and in the eye, only to be corrected by the top-down nerves activity of the visual cortex, at the posterior of the brain. As Sanida Gogic puts it, in helpfully simple terms:

When we look at the world around us, we must remember that the veil of human perception means things are not always what they seem. When you glance at an object, the image received actually appears inverted on the retina. Our eyes in fact see everything upside down, but incredibly, our brain compensates by default, allowing us to perceive the world right-side up.

The brain’s ability to be misled in this regard presents an eerie insight into the potential for manipulation of human experience. In a series of experiments, volunteers wore lenses to turn the world upside down. This reversal caused the brain of the subjects to stop compensating for the retinal inversion in order to see upright. When the lenses were removed, the participants saw upside down for a time.[5]

Figure 2:

That the description uses the normative process, as perceptual neuropsychology understands it, and yet renders it something outside the norm (as abnormal or pathological) is typical of this book’s insistence that the transitions and transgressions that occur between outer and inner are at the very centre of its effects. This is the case whatever category we examine of things that can be conceived to have an internal and an external existence and yet be treated as the same phenomenon. And everything potentially can be conceived as both an outside and inside: brains, minds, bodies, attachment groups from couples upwards, families, local communities and so on in ever increasing circle in which the line between what is outside and inside can be drawn.

Where, for instance, do we feel safe or secure in a world subjected to ‘mad electrics’ and ‘flaying nerves’? For electrical transmission and nerves operate to create the norms of human systems but if we see them as tuned to madness and violent acts like ‘flaying’ (we almost don’t notice because we hear frayed nerves’ at first, which aren’t nerves conceived of as being skinned alive), or electrical transmissions acting in ways beyond reason, if that is what we understand by ‘mad’. The turning of the norm into a scenario from a Gothic horror-story happens through the lives and deaths in this novel, even when the deaths are metaphorical of other kinds of endings than those in which bodies die.

I think this passage, though far from the richest in the book, is typical in its play with ‘facts’ from neuroscience and their translation into metaphors for an insight into the passage between the world as it is represented internally and its relation to the world presumed to exist outside and independent of that representation. One section of the book is correctly then, as I have suggested, called ‘Translation’ because it treats of the story underlying the strange representations of experience in the section preceding it, named ‘The Great Escape’, and translates them into the stuff of normative experience. When words translate experiences from the inside, as it were, and allow experience even outside the norm to escape or emerge out into that world, they constantly utilise all the resources not only of denotation but also connotation to capture that strangeness to conventional or normative thinking.

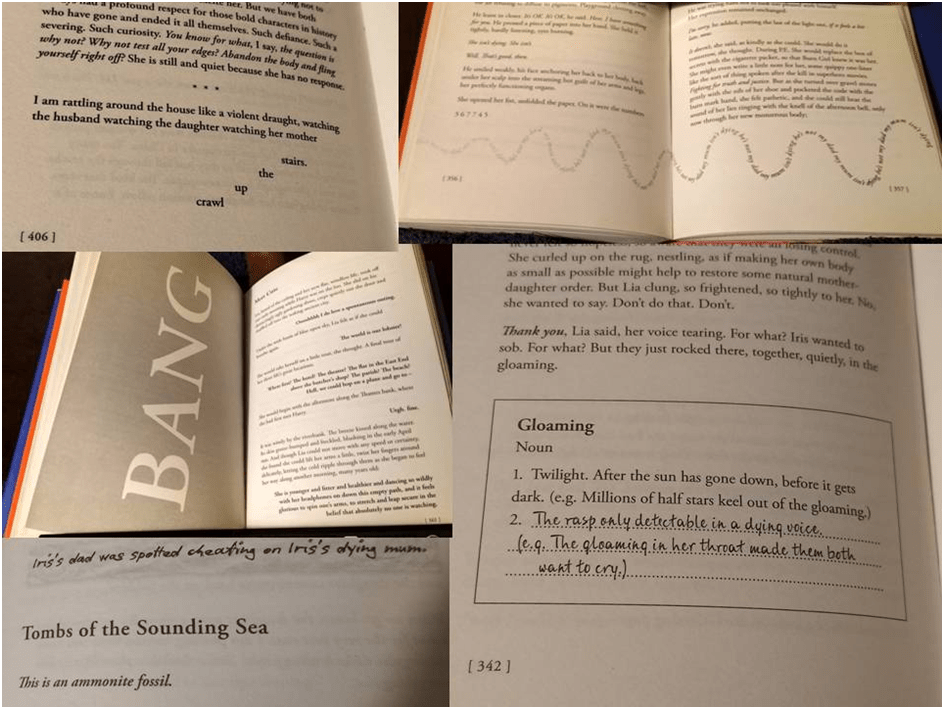

Figure 3:

Lia is an artist of visual colours and tones that play upon each other and interact. But she is also an artist whose relation to language is based not on the denotative meaning of words alone but their verbal resonances and associations (of their sound and look as well as their rich potentialities of usage in different contexts). Hence words extend their meaning into what they ‘sound’ like when articulated or voiced. We feel each part of some words as well as their combination in the normative appearance of the whole word. Words also change their meaning of themselves as a whole or their particles by variations of font type and size, order and sequence and the background on which they are printed or with which they are framed. It is almost impossible therefore to reproduce some of these in a quotation or citation. To get the feel of that we need to see as well as sound and articulate in Mortimer’s words (whether we do that in silent imagination or aloud) is to see how parts of word sounds or icons as well as of their whole form work upon us. To get the point, here are some examples, just to get the look of some effects. I will I hope deal with some of these in passing later in more detail.

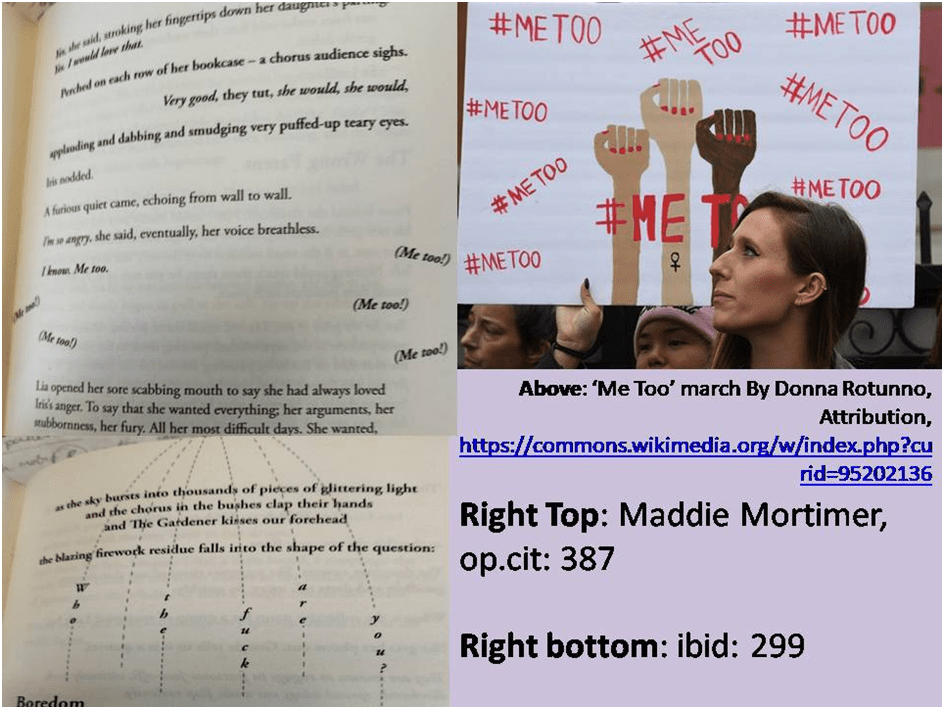

Figure 4:

Caleb Klaces in The Guardian review of the book attempted to describe these visual effects thus, collating them with the effects of visual imagery, where the visualisation is entirely that of the reader attempting to understand a metaphor:

Mortimer’s writing is endlessly inventive. It includes different fonts, stanzas, visual arrangements, lists and playful definitions, without settling on a particular approach. Images are often pleasing and convoluted, as when Iris considers growing up as a process of moving across from the world of her mother to the world of school in a “terrible act of osmosis”.[6]

There is a danger here in not thinking clearly about the relationship of words to their visualisation, for we need to consider the agency of different parts of the creative process of reading, writing and publishing design in that process. Let’s stick here with the writer and their relationship with the publishing design process including typesetting but much more. We have to think, for instance, about conventions of page ordering, including the convention of having margins (or ‘gutters’) to a page that are not usually allowed to bear printed ink on them, such that they only ‘frame’ the text. The publisher’s gutters are invaded many times with an effect on how the page looks and on the consequent meaning found in such transgressions of convention (the notion of ‘transgression’ itself being a first step in meaning).The strongest examples can be seen below, including one, using the phrase ‘Me too’, with sly reference to contemporary uses of the word to indicate women standing up against male sexual tyranny in patriarchy.

Figure 5:

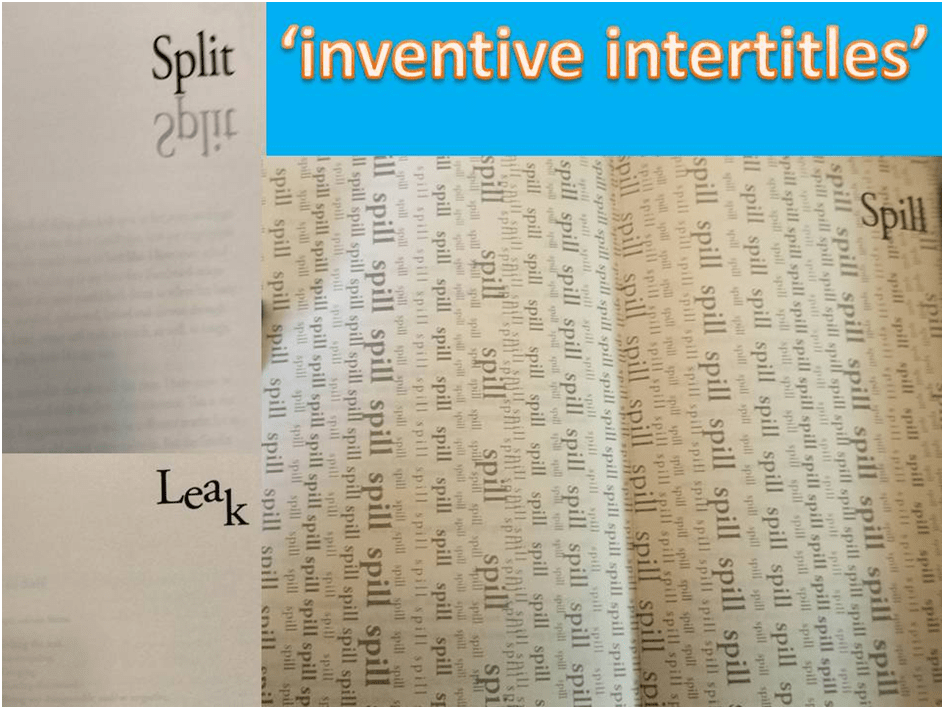

There are many examples in the book. Another example that is easy to see (but not as transgressive in my view as in Figure 5) is the wavy curve of repeated words articulating the rhythmic and wave-like spread of Iris’s words in the top right illustration in the Figure 4 collage above. This page follows the disclosure of secrets about Iris’ family origins and the disruptions of that occurs as a result in the childrens’ norms for the meaning of family units. Greying a full page in order to leave visible – by virtue of blank space – the visual shape of the word BANG is also used in the Figure 4 collage (at the centre of the column of illustrations on the left). The strange alter-ego of a narrative voice which runs throughout the novel (always found in a ‘signature bold type’) claims that some of the effects are merely it showing off: For if this BANG page creates the mental effect of an explosion, it also ‘allow(s)’ that authorial voice ‘the option of some inventive intertitles’ (using a word, ‘intertitles’, usually used of film narration and editing but not therefore out of place here). This narrative voice, by the way, Klaces describes well, using the novelist’s first words in the novel, as an ‘“I, itch of ink, think of thing”, an impish, verbose and mysterious narrator that appears to be neither human nor nonhuman’.

Such a creative narrator must be a publisher’s nightmare – the writer who thinks ink on a page must extend its creative potential as an artistic medium, as much as Tom Leonard does as a poet. It is as if, this narrator is a joyous Bacchic disruptor of publisher’s conventions. It disrupts just as a death by cancer of a significant individual does social groups (from ‘sociological’ dyads (like mothers and their single daughters) to larger groups such as local communities). Sometimes printing innovations merely extend the use of textual and ink background to further extend mimetic effects – to show, for instance what the paper notes in Burn Girl’s box of secrets look like once uncrumpled (bottom left in Figure 4 above), where there is also innovative play with font variations used for conventional chapter intertitles, and use of italics to indicate unvoiced words. Sometimes conventions are exposed to show how inventive reading minds have an almost innate foreknowledge of how concrete poetry differs visually and as a reading experience from poems using conventional visual shapes based on a regular metrical line. Here is an example from above a little larger:[7]

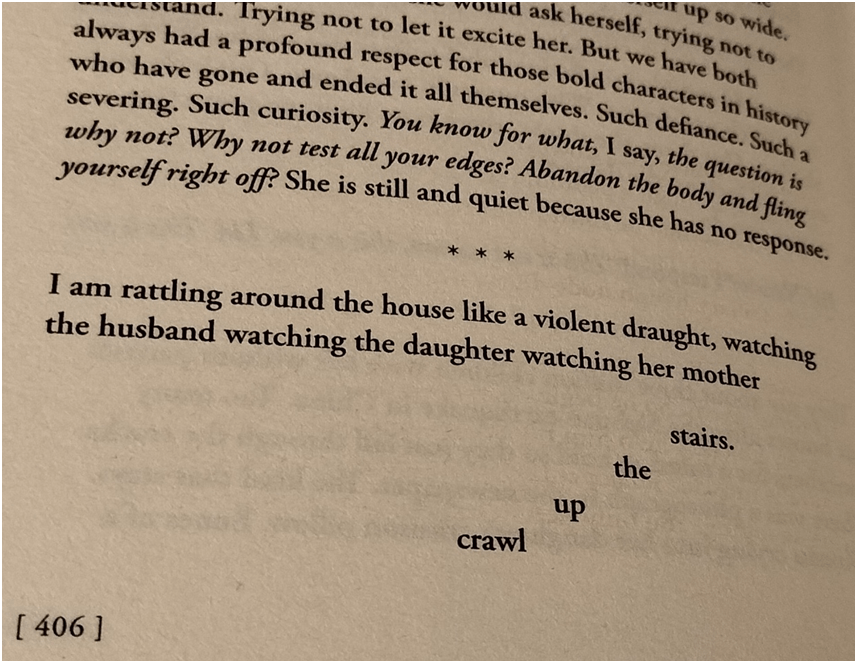

This is the voice of the alter-ego narrator, which speaks of Lia and other characters as if they were a part of themselves as a collective ‘We’. It speaks of the transgressive excitement of suicide. It does it with some play with its own look as text – in the reference to ‘respect for those bold characters’ (printed, as it is in bold typeface ‘characters’ (another name for the appearance of letters in a word). As Klaces says in the citation above, this is this narrator’s ‘signature bold type’. But the effect I want to notice is the play with printer’s conventions at the bottom of the page. It is the convention in Western writing and printing systems to read from left to right and from top to bottom on any page and between pages. This is the exact reverse of many Oriental languages.

In the example above, we change rapidly – I think all readers would do so – from top to bottom reading of the text in order to capture the concrete visualisation of ‘crawling up stairs’ in terms of the look and pace of movement up an arduous stairway, which still however preserves the left to right movement of the eye across the text. I sense the switching of codes happening as I read but it felt entirely nurtured, as if the meaning of the look of the text suddenly called on me to read more flexibly. This is typical of this book – for it both demonstrates and exposes conventions in basic literacy. I think we know Mortimer intends this effect because a concrete poem about going downstairs mirrors this one (reversed in shape as in a mirror of course) earlier but which uses ALSO the habituated left to right, BUT NOW of course ALSO top to bottom reading expectations of its reader.[8] Both ‘poems’ use the reader’s own basic – perhaps innate – structures of grammar and word order (I feel a reflection on Chomsky coming here but I will resist) to show invention carries readers with it rather than imposing on them, even if it subverts some expectations on the way. And we know that because we register these two ‘poems’ with different effects on our need to revise our reading type as we progress.

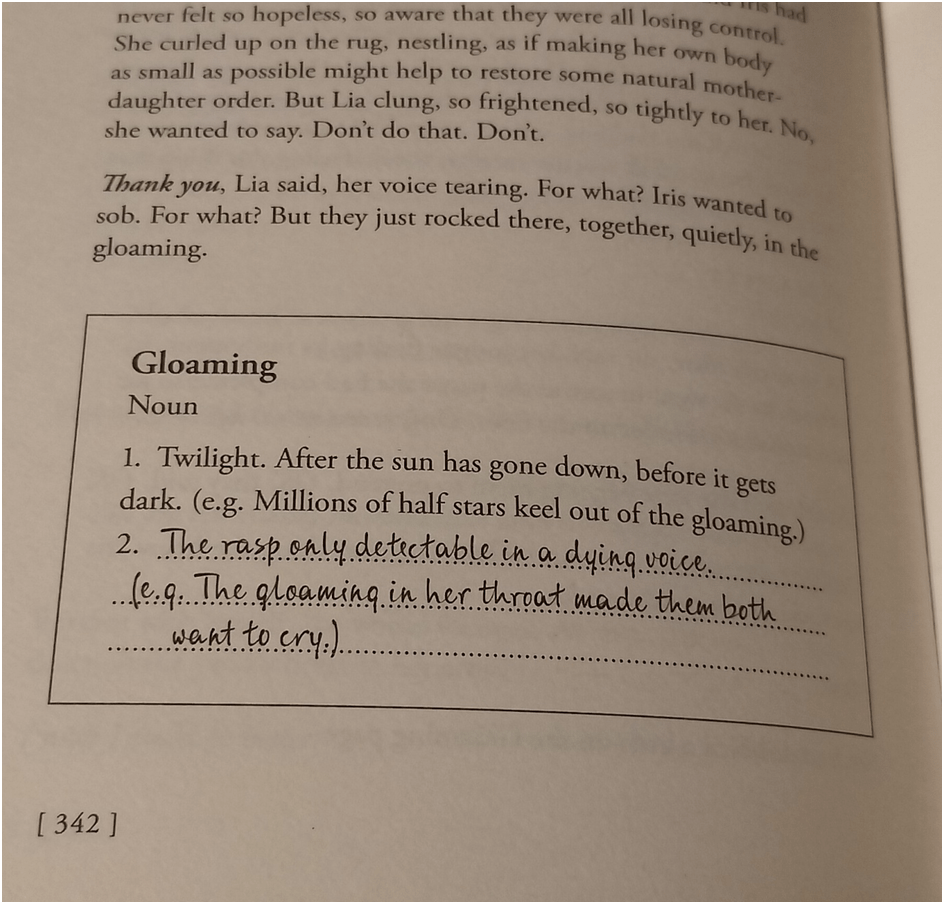

More important is the fact that these points about language grammars and lexis (especially the latter) are central to the story and its characters for Lia is a writer and illustrator whose obsessions with lexis are translated into an occupation as a writer and illustrator of innovative educational books. The book she is working on through this story, but will never herself complete, is quoted from sometimes. In doing so even its printed format (in which each word of interest is both ‘defined’ and printed in a box) is reproduced. The book is called The Children’s Guide to Lexical Spectacles. Iris will commit to complete the writing of this book, in lieu of her mother, on the latter’s death and in honour of her. Her ability to do so is based on the ‘many years of bedtime word-talks’ enjoyed by them in interactions essentially about learning creative connotative thinking.[9] We see these ‘definition boxes’ throughout the book as they are being revised by Lia or Iris (how would we know for the exact location in time of the state of this writing is not made transparent) with written definitions that start with the denotative. These ‘definitions’ are followed by less typical and connotative (and sometimes personal) interpretations of the word written in as if in pen (but in fact, of course, in an invented character script made to look like human writing). From the start we are told these definition grids would contain a typed ‘lexical entry’ but be followed by : a blank space/ / to fill in one’s own definition’.[10] As the story develops, we realise that some of these ‘pen’ additions might have come not from Lia but from her daughter, Iris.

A brilliant example of how this builds on the novel comes from the example I gave above and will repeat here:

It matters who may have written the definition given here as number 2. For if it is either or both Lia and her daughter Iris, it dramatises the circumstances of their relationship as Lia dies most painfully but also most beautifully in the acceptance of discomfort and pain; deepening the connotations of this word elsewhere in the narrative. Yet we had already learned from the young Lia’s adventures in ‘pigment-science and etymology’ that the word for colour ‘Yellow’ (a code sometimes for daughter Iris) derives from proto-Indo-European root ‘”Ghel”’,”to shine”’ and from which many other words including ‘Gloaming’ stem.[11] The word ‘gloaming’ appears as you will see in the text above: ‘But they just rocked there, together, quietly in the gloaming’. Is the rasp in Lia’s dying voice intended here, or is it flashed back retrospectively in our onward reading where the word recurs?[12] Only a reader willing to actually read as richly as Lia writes can say so. How lasting are those connotations and how, if at all, do they spread through the novel’s use of a word like this? GLOAMING one of the intertitles of the section in which this citation appears, which tells of Lia having ‘dribbled a little on the Gloaming page’ and speaks of her hopelessness, as her publishers release her from her contract for the book: ‘She croaked it like the detail of a bad dream’, as if her voice contained its rasp in speaking. The word returns later, in the voice of the alter-ego in bold type and in the free verse characteristic of the voice, near the very end of the novel: ‘Nothing but the gloaming in my throat / These little rattle-breaths, retiring up the stairs for the night’.[13]

Plays on words are poignant elsewhere in the novel, as in many other good novelists, and are used brilliantly. The cruelty of Lia’s friend Connie, possibly unconscious to its speaker, is made clear by a drama that takes place in the consciousness of Lia hearing the same word, ‘wasted’, with different denotation – the second one in urban ‘slang’ meaning drunk – but similar (for the reader) connotation.

Outside, somebody was vomiting by the butcher’s shop bins. Lia could hear the half-howls of delighted voices saying things like, …, but Connie wasn’t listening.

I just think you’re wasted if you’re not drawing or painting or making something. Anything. She said, …

I’ve never seen her this wasted, a voice leaked up from the street below, a kind of brutal disgust, disguised in her tone.[14]

Whose ‘disguised’ disgust is registered here as a connotation of a speech that might claim not to denote disgust? Is it the person by the bins speaking of her drunken friend, or is it Connie of her friend, Lia, whom, in Connie’s eyes, has given up work on significant artworks, or is it Lia about herself? We cannot know. The import is that the method of the book is to show how flexible is the interpretation of words and the range of meanings possible in tonal variations in voice or heard by the ear – especially the ear interpreting a literally, if not metaphorically, toneless print.

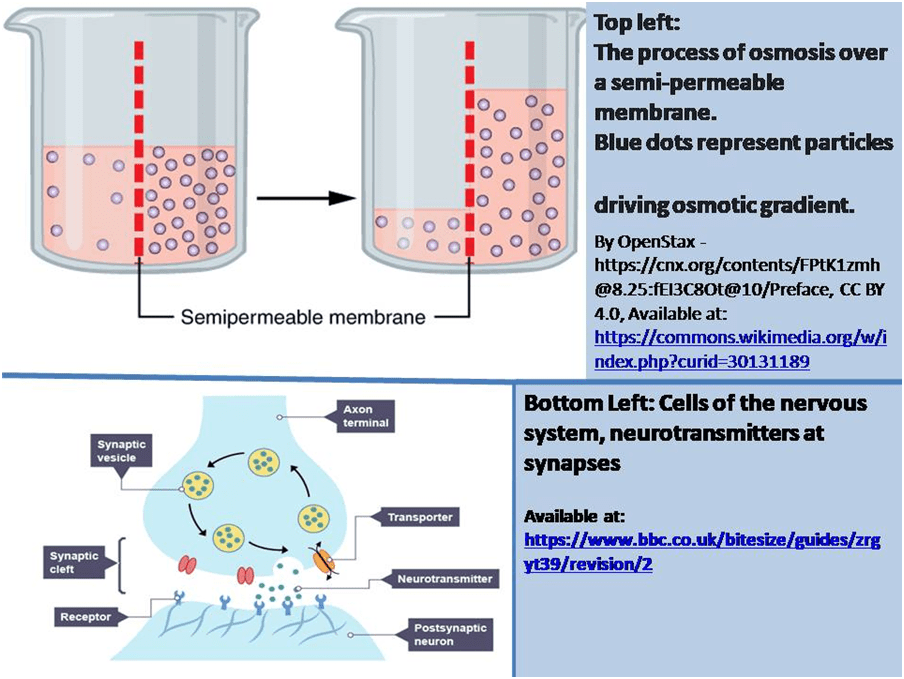

But really important in this innocent passage otherwise is the place of the word ‘leak’ – as Lia registers voices that had ‘leaked up from the street below’. Leakage is possibly one of the greatest metaphors for how this novel must be read and / or heard. For meaning leaks between different domains – from settings with otherwise insignificant characters to those containing major players and themes of interaction as here, or between persons interacting, or between a person and their self-representations in words about their visceral bodies. There is leakage between bodies, and between separate domains in families and between different communities. And what goes on interpersonally and between groups also happens intra-personally. Inside bodies these leakages happen between representations of different agencies whether thoughts, feelings, pathologies, pathologised and healthy visceral organs, chemotherapies or ‘natural’ chemicals like hormones and neurotransmitters whose purpose is to communicate but which often leak in to all kinds of side-effect. Indeed the whole theory of synaptic transmission and other cellular interactions across membranes is based on notions of leakage in and out of those membranes that form connections at synapses. It is not only body sub-systems that might leak into each other however: Lia remembers ‘that terrible Auden poem’ about the incidence of cancer amongst childless women and retired men:

…

It’s as if there had to be some outlet

For their foiled creative fire.

The thought was too dark to dwell on’.[15]

Leaking has many near-synonyms in the novel, although they often connote a very different pace and urgency of emission though a containing membrane or otherwise sealed restraining lip. Leak, Spill and Split are all used as ‘inventive intertitles’ (see above), often with illustrative calligraphic effects.

Variously these describe the transmission through a semi-porous membrane, like that of a cell (such as those at a synapse in a nerve cell) through which material may ‘escape’ a membrane container. They show how matter is ‘let out’, or in the case of cancer cells in the body ‘let in’ by these transactions. All of these near synonymous phrases are used in the novel, some of which I will show. Thus the voice of the cancer itself, which some argue is part of the identity of the alter-ego narrator, argues that with the visceral brain: ‘There is always a way in, / a latch left open’.[16] Elsewhere it rejoices in getting in, secreting it’s victory in a footnote through ‘a break / a shatter / a squeeze / a leak /’. ‘ … /And just like that,1’: the footnote to this superscript reads: (‘1 I’m in’).[17]

Other near-synonyms are nouns that have been verbs such as trickle, dribble, bleed, ooze, blot, stain, spill, split, flood. Yet another is the term from physical science, osmosis. For instance in a section called ‘Scripture’ we are told that a membrane is a container (whether it appears around a biological cell or body), a skin tissue of kinds, or as the ‘itch of ink’ narrator interprets ‘a bit of Job (10: 8 – 11’ which Lia inscribes on her own skin):

Did you not pour me out like milk and curdle me like cheese?

It’s a mystery. The way sheets of knitted skin are the only things keeping us all in.[18]

The metaphor (‘a terrible act of osmosis’) is applied to the development of child to adult in Iris which the young girl thought might be a simple ‘process of / moving across from one to another’ but which is also sometimes, as Lia explains, sometimes a ritual scarring like a self-inflicted cigarette burn in the skin. She burns herself to win acceptance from the most adult-seeming of her school friends, the person who hereafter to be ‘Burn Girl’.

Of other near synonyms here are examples which tell of things being let out from porous containing membranes (whether blood inside or outside the body or ink (the life-blood) of an ‘ink-thing’ storyteller). Thus, Lia, imagines the smell of chemotherapy for cancer as a smell escaping the containing skin. In some examples, such as the first, the idea of the letting out of ‘dribble’ is linked directly to leakage. Here are 5 examples:

- ‘Dribble had started to leak from the corner of Anne’s lip, beginning a glistening journey down the hard line of her chin’.[19] ‘Time distilled in / the nib of a dribbling / syringe, …’.[20]

- ‘By the Thames bank, watching the shards of an unseen message blow quietly into the water, ink bleeding out from its wounds’.[21]

- As Matthew’s sperm cells travel to effect Iris’ conception within Lia, though ‘most don’t make it through’, he lies with her again and she ‘felt a little residue of his wet heat ooze from her’.[22]

- ‘Lia woke up next to a large black hole. The ink from the ballpoint had leaked slowly through the night into her sheets’.[23]

- ‘Daughter pretends not to notice. Instead, she tells us about her night spent stuck inside our body. The lightless basement of our liver. The banister bile ducts and empty pink corridors. … Only I was soaked in yellow, she says, and the colour spread into everything I touched; it climbed up all the walls, it got into all of your veins, it stained and stained –‘.[24]

This is why I choose the (for me) very brief citation for my title here: namely. ‘‘…, it seemed as if her anatomical nightmares had begun to bleed into the days’. [25] A bleed is the commonest kind of leakage in the novel and one that occurs inside and outside bodies where containing surfaces fail, or an unknown function of an orifice in the body (the vagina here) becomes un-secreted for young girls heretofore kept ignorant of menstruation. Lia’s story, for instance, tells of her discovery of her first sight, at the lake on a picnic with school friends of ‘red blood making it’s quick way down the inside of her thigh’ and her association of this with the ‘ceremonial unclean’.[26] It is a powerful moment.

After a ‘Long Night’ of sickness Lia feels ‘the first leak of sun after / a year of lightless winter’.[27] Secrets leak; trying to listen through what is obscured by her father’s dementia to hear revelations of his past life, Lia still has to ‘decipher the leak of a secret’.[28] A central story in the book concerning Iris tells of the slow, managed release (like leaks to the press), of secrets contained in a box and regulated by the malicious Burn Girl. Sometimes unexciting male lovers leak sperm rather than deliver it purposively and forcefully. Indeed this provides the writer with one of the funniest descriptions of oral sex delivered by a woman to a man I have ever read (note: that may be because I have not read any, but it’s funny, nevertheless): ‘/ it took the boy ten minutes to come. It dribbled into the back of Lia’s mouth without force or urgency and tasted like salty lemons, coins, chlorine’.[29] And finally good husbands, sleeping alone whilst their wife dies in hospital, uncharacteristically get drunk on vodka to blot out the strange leakage from the bedroom walls of ‘the memories of all their peaceful nights’ that ‘perspired out from pulsing walls’. The drinking session itself is described as: ‘Leak of ethanol stinging down his chin before dropping to the floor’. [30] Leaks are also spills, a word that also describes in this novel the consequences of both a house fire and, from the beginning and more than once, ‘volcanic hatchings’, such as Vesuvius in 79 AD.[31]

Cells too leak in some descriptions of the destructive pathogenesis of cancer or the ambivalent action of chemotherapy. But they leak in constructively creative interactive effects inside and between cells in the conception of a child. This is painful in that one such leakage is in the meanings to Lia, and to Iris, between the meaning of having a child or developing mutating and travelling cancerous growths through leaky body systems, often described as the leakage of colours into each other and the process of dyeing materials, such as ‘shit’ by beetroot and the characteristic ‘cold chemo stench’ that is ‘sweating’ through too porous sickly skin.[32]

There is far too much to say of this superb novel but it would be a worthy debut winner of the Booker and would cause innovation in literature and writing about illness for it is serious about the liminal experiences involved and the transgression required to write truthfully about it. Most of all it shows that we can’t describe without understanding the complexity of language beyond denotation because ‘even words are made up of little internal transgressions’, that make it plain to us that normative thinking about illness is not good enough or rich enough or covers enough perspectives of the meaning of sickness and death. Representation is about cutting through lies that we use to defend us from truth before deeper truths might be discovered. In the section on the liminal called ‘Threshold’, the writer says it thus: ‘even language disobeys itself, because most living things carry the instructions for their own undoing everywhere they go’. [33]

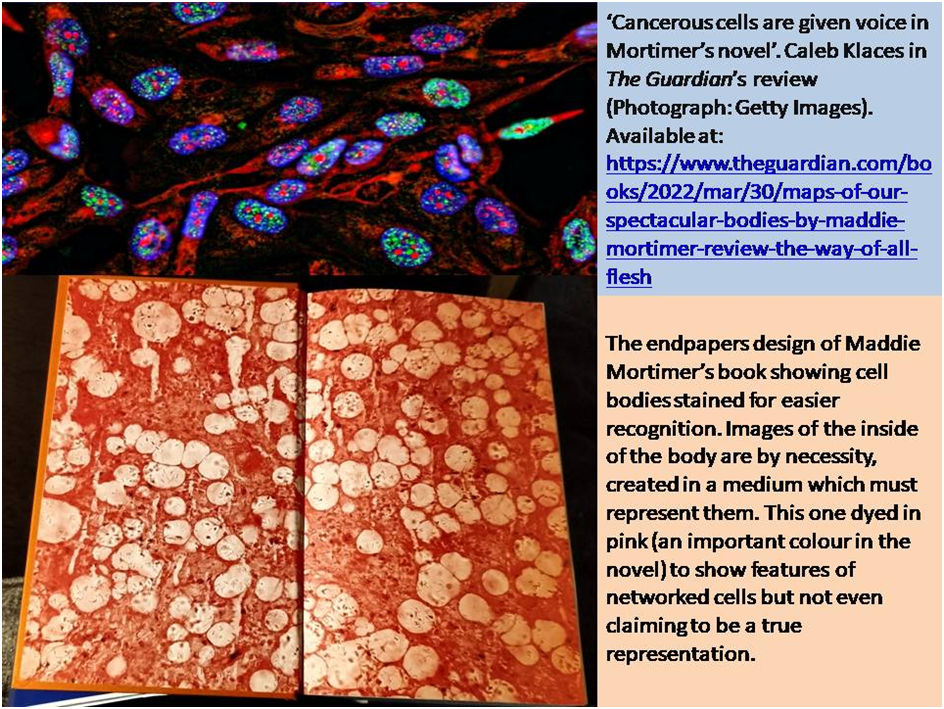

There are easy ways of showing this is so without further work on the painful material of this novel and the sources that the author has hinted come from materials metamorphosed from parts of her own life experience. Even visual representations in medical and anatomical representations may pretend to show realities but are in fact governed by agreed conventions of colour coding (or even ones to create the effect of the internal drama of the process – say of the occupation of space that should be held by healthy cells by ones that are ‘cancerous’) that bears no relation to what the depicted anatomical and micro-anatomical features actually look like, as in the following example ( I gained something then from my OpenLearn course on Medical Imaging).

Please read this novel. At the moment I see it as a Booker winner and would doubt any shortlist that does not contain it. I will report back from seeing the author speak at the Edinburgh Book Festival.

All the best

Steve

ADDENDUM: Edinburgh International Book Festival: Maddie Mortimer, Tanya Shadrick & Catherine Simpson: Our Bodies, Ourselves, Fri 26 Aug 10:15 – 11:15, Northside Theatre, Edinburgh College of Art.

This event was a fitting setting for the novelist and the novel; but not because of the superficial similarity of the subject: the story of women living with a cancer diagnosis and the experience of being under treatment for it. It was wonderful as an example of the honesty to their own vision of each of the three writers. Moreover, the way they and their skilled interviewer modelled fruitful and entertaining conversation on a difficult topic which takes as its main burden the dangers of positive psychology paradigms and the social practice of enforced cheerfulness. Yet here was true learning about how we accommodate talk to include the negative events in lives and to learn how to listen to the experience by those people experiencing those events. There was much to learn about the differences of method of each writer and the attitude those comparative methods took to first-person revelations by writers. That this was a central issue in Mortimer’s novel helped the others to show why they felt the first-person was still necessary to their writing. It was a beautiful event.

[1]Maddie Mortimer’s (2022: 345) Maps Of Our Spectacular Bodies London, Picador

[2] Ibid: 401

[3] Ibid: 399

[4] For recurrence see for instance ibid: 18, 117, 126

[5] Sanida Gogic (2020) ‘Optical Inversion’ in Al-Rasub Available at: https://alrasub.com

[6] Caleb Klaces (2022) ‘the way of all flesh’ in The Guardian [online] (Wed 30 Mar 2022 11.00 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/mar/30/maps-of-our-spectacular-bodies-by-maddie-mortimer-review-the-way-of-all-flesh

[7] That Mortimer is aware and intends to invoke concrete poetry is clear. On ibid: page 230 there is a poem whose words outline a peace dove, Facing it,(page231) is a poem that seems an neuro-scientific version of the same message (of the redemption of time) in a similar stanza form as George Herbert’s Easter Wings, the archetypal model of a concrete poem, though not so called in seventeenth century England.

[8] See ibid: 59

[9] Ibid: 31

[10] Ibid: 32

[11] Ibid: 24f.

[12] Maddie Mortimer op.cit: 342

[13] Ibid: 428

[14] Ibid: 327

[15] Ibid: 135

[16] Ibid: 173

[17] Ibid: 233

[18] Ibid: 96. For Job Chapter 10, see https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Job%2010&version=NIV

[19] Ibid: 39

[20] Ibid: 428

[21] Ibid: 342

[22] Ibid: 378

[23] Ibid: 16

[24] Ibid: 275

[25]ibid: 345

[26] Ibid: 108f.

[27] Ibid: 193

[28] Ibid: 351

[29] Ibid: 192

[30] Ibid: 389

[31] Ibid: 85

[32] Ibid: 218

[33] Ibid: 383

One thought on “‘…, it seemed as if her anatomical nightmares had begun to bleed into the days’.[1] This blog contains my personal views of Maddie Mortimer’s (2022) ‘Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies’, BOOKER Reflections LONGLIST 2022.”