Arinze Ifeakandu describes the discovery of his amative preferences when he was ‘a little boy’ thus: ‘But it was boys who made my heart go wild. Boys were incredibly beautiful to me, not in the way that girls were—girls were beautiful in factual ways: fine girl. Boys, I wanted to hold. Soon, I began to write stories that satisfied this longing, especially as I began allowing myself freedom to be with, and think of, boys. Representing that love was my way of perhaps participating in something my heterosexual peers enjoyed without second thoughts’.[1] This blog reflects on how and why we need to realise that queer love stories can be and should be both more imaginatively conceived and grittily realised than those which confine themselves to heteronormative attachments. This is a blog on Arinze Ifeakandu’s (2022) God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson and previews an interview of him with Colm Tóibín on the 24th August 2022.

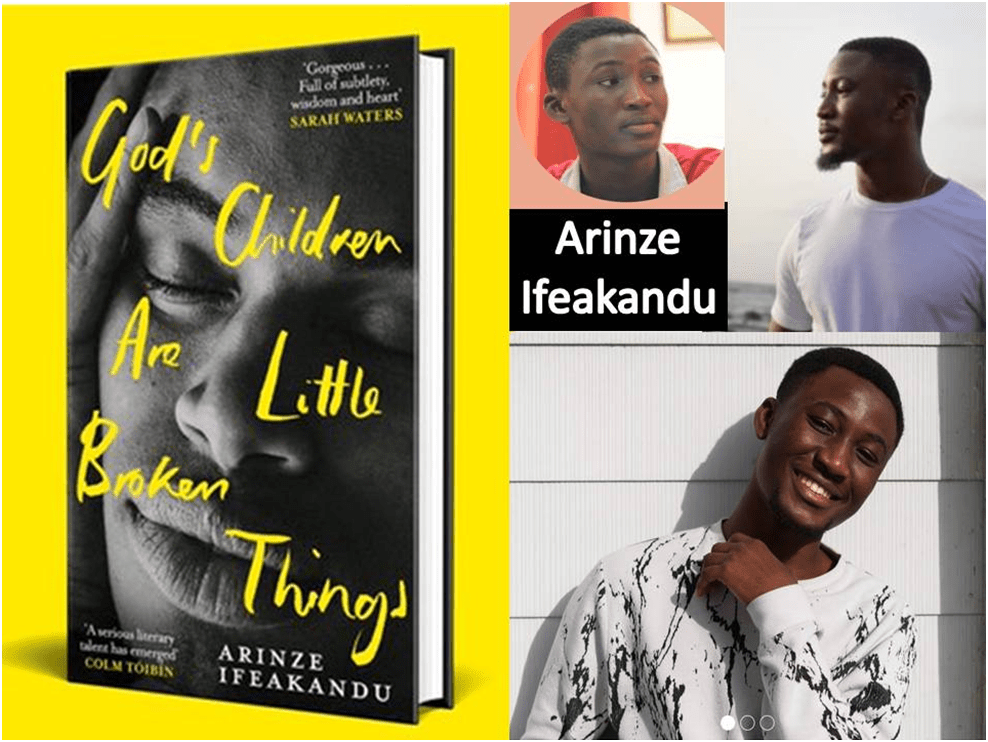

NOTE: I have already blogged on the pre-publication of one of these stories, ‘Happy Is A Doing Word’. It is available at this link or the one in the footnote.[2]

The title story of this collection, ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’ was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2017. To write here therefore of this story collection as a collection of ‘queer love stories’ might seem to appropriate it for a concept more prized in the Global North and West than the Global Southern and East. But let us not make that mistake in understanding, though Ifeakandu himself, now a citizen of the USA, insists that there is some point in creating a queer literature that recognizes that, as he says in an interview with Ucheoma Onwutuebe that: ‘Homophobia is everywhere’. And there is more than a hint in what follows that the experience of the homophobia in Nigeria has commonalities with that remaining in the USA. Thus paradoxically queer people in Nigeria found the draconian 2014 Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill had ‘sparked a widespread conversation’, whilst, having travelled to the USA hoping for ‘the best gay life …, and freedom’ because that life is ‘protected by law’, he also found ‘a lot of people were closet in Iowa, dealing with homophobia, which manifests in many ways’.[3] Much of the power of these stories, however specific each is to the life, culture, law and culture of Nigeria, address circumstances which hide and enclose queer love and queer sex in a closet, the source of a social power to ‘hide’ their pleasures and feelings, that happens across cultures. There is genuinely no single answer to the question asked of the two young boys who find pleasure in each other’s bodies; the question being: ‘Who taught them to hide’?[4]

And I think I want to dwell on how brilliantly innovative Ifeakandu is as a new queer writing phenomenon. He takes now stock themes and paradigms of the genre of gay fiction that have shaped much of the literature so far, such as ‘coming out’ stories or the notion of a discovered identity (uncovered that is from some kind of hiding of that identity underneath ones more acceptable to social and cultural norms) and shakes them up somewhat. This, to be frank, has long been needed because they are a function of propaganda rather than of human truth. This is for at least two reasons.

First, these mythical forms of real experience blind readers to the complex and nuanced that continues to be at play in the performance of being who one is. It is clearly mistaken to hang a notion of ‘a true identity’ based on only one aspect of our complex being rather than to acknowledge intersecting fragments whose coherence is often only idealised or temporary. We can be identified and identify ourselves as white, black, brown or none of these labels (for in doing so we often invoke a level of reality that is more politically descriptive than about some truth) or as differently enabled in some way, or different in class, sex/gender or other category of being commonly invoked.

Second, ‘identity’ is often used as the only aetiological factor, or at the least the underlying commonality, of all the actions or behaviours, sensations, thoughts or feelings of the person so described on which a story turns, whereas, for instance, sex between men can be, and is in some characters in Ifeakandu motivated by other things entirely, such as deprivation of other outlets or restrictions on sex with women that seem in some moral regimes greater than on sex with other men.

I detail these reasons because of a reading of title story ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’ (hereafter ‘God’s Children’) on its appearance on the shortlist for the Caine Prize in 2017 in Brittle Paper. The deputy editor of this magazine, Otosireze Obi-Young, a young writer and curator of arts too who prefers to be known as Otosireze only, has focused on many occasions on refining what we mean by the promotion of LBGTQ+ literature that sees its role not in the formation of a separate ghetto type genre of writing but as a recognition of the very real and indivisible existence of sex between men as part of a larger literature that has hidden that aspect of sexual and amative lives alone, regardless of labels for identity.

Anne-Christine d’Adesky in 2019 has spoken of Otosireze as opening up issues that are not confined to well-trodden themes and myths of past gay or queer writing. Thus she says beautifully:

Otosirieze’s own fiction began to flow, and he began writing a short story modeled on a past unrequited crush for a straight boy. Such relationships usually end badly in African fiction about gay lives—often with a murder or suicide. He shared a different story, and his subject—a gay-straight male friendship—addressed queer male affection. “We need to tell the truth about our lives, the many truths about masculinity,” he said.[5]

For some his ideas in criticism of a boundary put around LGBTQ+ fiction aren’t easy to understand clearly, though his Wikipedia entry tries to do this (see link to his name above). But the review that Otosirieze’s chosen reviewer of Ifeakandu’s story, Kelechi Njoku, does say the same things, even if its prose is not as straightforward as one might like when used by greater masters and appreciators of what finely structured sentences achieve. For instance Njoku seems rather dismissive about the possible existence of a typology or icon of queer writing in the opening of this sentence, whilst denying that the story promotes that typology in the second half: ‘Even as “God’s Children” carries one of the most recognisable tribal marks of nascent queer writing – the Tortured Homosexual – the story rolls gently to soon reveal that Lotanna isn’t so much tortured as he is watchful’. As I understand this sentence, Njoku is critiquing a possible reliance on stock characters that oversimplify how men who have sex with men are inserted in ‘queer writing’ but showing that Ifeakandu is seeing these men in much more complicated ways that tells hidden truths about deceitful appearances that sustain both heteronormativity and homonormativity as oversimplified descriptions of sexuality built on fascination with easily understood binaries rather than multiplicities of interaction in gender, loving and even sex. What he picks out of the story are descriptions of the realities of behaviour that don’t fit comfortably into typologies of what love between men might be like, particularly in its estimation of ‘gentleness’, and sexual behaviour which confute easy understanding of the relation of behaviour to both emotion and sensation, as in this describing, beautifully and comically and non-erotically (if we type these behaviours) description of ‘sexual arousal’.

He stifled a giggle (you would later learn that he did that often when he was turned on, stifle a giggle, so that it sounded like a snort).[6]

Indeed this sentence is richer even than this in its context for it forms part of a scene we must decide in the process of reading the whole story whether this describes a process of seduction of Kamsi (‘so small, so fragile’) by the supposedly heterosexual jock Lotanna. It is made clear Lotanna is more powerful physically and socially and in sheer size than Kamsi, though he may claim that he would not use that power aggressively. The whole passage uses language that emphasises the dangers and strategies involved in the sexual process when such power inequalities exist. Lotanna thinks of how Kamsi ‘had given himself up so easily’ almost as if in a conquest. He had Kamsi’s ‘hands pinned down’ and urges relaxation as a forerunner to anal penetration of the young man. On hearing the latter’s “No”, he for ‘a while … towered over him’. For, if Njoku is correct that Lotanna is ‘watchful’ not ‘tortured’, it is in part because we recognise that even homophobes have a point when men use power over those less powerful than themselves whatever their sex/gender, and whatever the reality of your readiness to be gentle or caring or believe yourself so. For Kamsi’s story is one of not only male ‘heterosexual’ oppression as a man who liked men, and feels that he is ‘gay’, but of the fact that these oppressors also use their hidden liking for sex with cute men to ‘beat the gay out of me, he said. But that I was so cute they’ll have a little fun raping it out of me’.[7]

The notion of identity liberation which emerged out of the gay activism of the 1970s, necessary as it may have been historically, has always had a difficult relationship with the acceptance of details and complexities (practical, imaginative and ethical) which it has too often seen as an aspect of pornography, and thus continued to hide or marginalise in its second-class and second-rate literature. This was not so earlier in queer history, especially in the USA, as I have tried to show, for instance, in blogs on Glenway Westcott and Charles Henri Ford’s and Parker Tyler’s The Young and Evil . Ifeakandu is specific in showing us that it is the learning the sexual process by young boys which is at the core of what gets hurt by being hidden and associated with something dirty or unpleasant.

I have tried to explore this in my blog on ‘Happy is a Doing Word’ because that, like so many other stories deals with the way boys might learn about the mechanics of mutual acts that cause pleasure and which remain necessary to ‘hide’. The discovery of gay identity sometimes is only another strategy in encouraging this secret arena of human action, since it omits the fact that sexual pleasure is not a function of identity but of bodies and their specific allowance of being pleasured or not by an imperious socialised mind. For instance, the character of Somadina is interesting in that story because he is not and never will be happy to call himself gay and that this maintains and increases his desire for a hidden continuation of sex with men, whilst Binyelum grows up gay but not therefore more able to develop the relationships he has with men beyond a path to a certain identity and its label is endemic in Ifeakandu. Similarly in ‘Alo̗bam’, Ralu ‘liked girls and he liked boys, but it manifested as a general curiosity, roving and aimless, without fire’. His ‘aimless’ confusion continues into his misdirection of libidinal desire, romance and friendship. He grows to desire Makuo only when he comes to know him as a friend but first has orgasmic sex, the method unclear, with Makuo’s brother, Obum. The key phrase in all this is ’unsure what to do to make that happen’:

Obum’s lips parted in a sweet, low chuckle, Yeah, he muttered, fuck yeah. They clung to each other. Ralu said, Your turn to come, unsure what to do to make that happen, but Obum shook his head, Just hold me, he said, that is all I want.[8]

In all of these stories complexities of learning sexual process and preferences within it, for pleasure in active stimulation of different domains of the body and the link of that to ambivalence about certain aspects of sexual interaction, matter a great deal. A key one is anal sex, which is problematic in many stories. For instance it is crucial in ‘God’s Children’ because it is only at this point that Lotanna learns of Kamsi’s childhood rape by heterosexual and homophobic men by that act. In ‘What The Singers Say About Love’ the narrator learns to accept anal sex because his lover, Kayode, teaches him a means of being consensually comfortable (‘Are you ready, babe’) about an act otherwise associated to aggression and mutual self-hatred (‘the boys who dumped their anguish in my body’).[9] An even better example is the dialogue in ‘Good Intentions’ between Doc, a university lecturer, and a student. Doc is being investigated by a tribunal of his peers for having sex with male students following more than one complaint. Doc sees those peers as themselves people who show ‘the heartlessness of powerful men’ (for he knows they use more power over their female students in exchange for heterosexual encounters): however, we are continually querying whether this phrase does not in fact describe Doc too.

This imbalance is even more poignant when it is clear that the student lover wishes to have anal sex with Doc.

The rug scratched your naked back now. You rolled onto your side, facing him. “Are you asking to fuck me?”

“Maybe,” he said. He smiled shyly, looking briefly away. “I promise I’ll be gentle. Soon, you might even be begging for it.”

…

“I cannot see myself getting fucked,” you said, standing up. “I can’t.” You were surprised by how angry you sounded.

“We’re only talking, Doc,” he said, sitting up. “Why are you getting angry”.

“Please, let’s free this talk,” you said, hoping it would dispel the tension. Under different circumstances, he would have laughed and asked if it didn’t feel good, speaking like a true Nigerian.

“Why do we have to free the matter?” he asked. “this is the first time I’m bringing it up, you don’t have to agree, but you cannot shut the conversation down. I stopped making pro-gay posts on Facebook because of you. You said they put you in a precarious situation and I agreed, even though I don’t quite agree. I quit volunteering at the NGO because there were ‘too many fem and open gays working there.’ What have you given up for me?”[10]

This is brilliant dramatic dialogue in which conflict hangs around power discrepancies and the equalities demanded, but never quite giveable; of the relatively powerful giving up powers in demonstration of love. Doc feels he can try by using the ‘code’ of a lower register of language than is his wont (‘speaking like a true Nigerian’) but his bluff is called. Anywhere where the student might have power – as an open gay man associated with others or on social media (relatively lowly positions of power though they are, have to abandoned to preserve Doc’s own institutionalised power and status. Even independent thought has to be given up by agreeing where you ‘don’t quite’. To take a role thought of as dominant sexually (because heteronormatively male – the fucker not the fucked) will be resisted too for similar but less socially public reasons. Perhaps what the lad misses here is the effect on Doc and asking him to imagine himself ‘begging for it’ and Doc’s recognition that such subjection, as he may see it, is possible for him imaginatively even if it strikes his ego as humiliating. Nothing, ironically, is less ‘free’ (in a different usage of the word – in the passage it is meant to mean ‘let the subject go or be dropped’) than this passage for it is sex bound not to the mutual learning of the pleasure of bodies but of the enforcement of social regulations which make us differ from each other in terms of fixed power relationships.

In ‘The Dreamer’s Litany’ married small shopkeeper Auwal feels he has access to ‘a wonderful feeling of power’ over a man ‘who smelled and looked like money’, and aptly named Chief, lowers hid head and wraps ‘his lips around Auwal’s dick’.[11] Yet Chief seen in his moments of real power as highly successful retail entrepreneur no longer looks ‘the small, almost pathetic man who knelt on a dirty floor’ also rules the sexual menu, saying when Auwal attempts further intimacy after seeing such power, and because ‘it was what lovers did’: “I don’t like to kiss’. So much about the power that pre-structures this relationship is felt to hang on this. Chief offers his neck not his lips and Auwal feels that this ‘is not the sort of surrender I long for’, for it is no surrender at all but a way of the Chief maintaining superiority of power. [12] If you read carefully, you will notice that Auwal’s final humiliation and belittlement hangs around this question of the domains that men allow each other to explore within any relationship. Finding the young Chima in Chief’s flat later asks Chief: “You kiss him?”

Chief looked up, arched an eyebrow, “What?”

“Did. You. Kiss. Him? Auwal, angry, had slipped into Hausa, English too unreal for his surge of feelings.

“Of course!” Chief looked exasperated.[13]

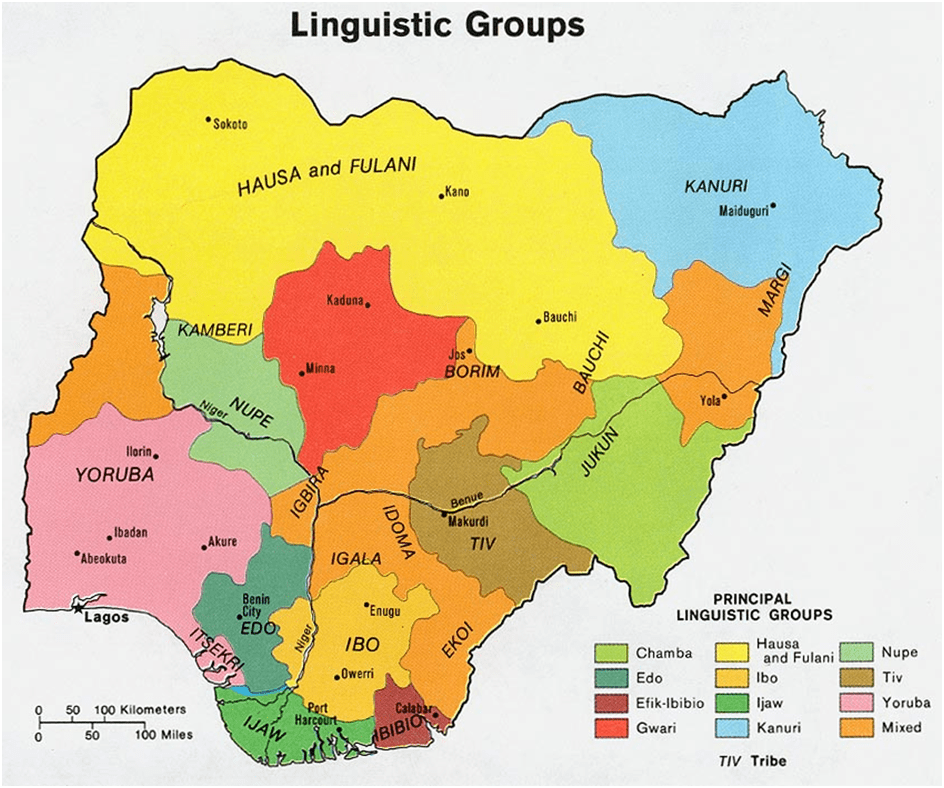

It is not merely that Chima is a very young man but that he exudes the status (one that marks people who do not speak in Hausa or have unruly feelings but restrain them into English) that enables him to seem an equal to Chief. Languages are of course slippery markers of meaning that can change according to context and this is important here as we see. But we see it massively too in all the stories. The use once of language as tribal identification is now in modern Africa also a means of distinguishing class but Ifeakandu is clear that its exact meaning is a matter of context as he told Vivian Eng for the PEN interview.

Language is an aspect of characterization, I think. We code-switch in order to feel safe or to communicate more effectively or to flex, or intimidate. Like the clothes we wear, our speech reveals, sometimes, our class. I used language in that way to show clearly the—sometimes—shifting dynamics between characters. Igbo, for example, is sometimes used for endearment, but at other times, it alienates, rebukes. Everything depends on context.

The final revelation that Auwal is not kissing material because he is associated with something rougher, tribal and lowly in class (even animal) comes when Chief shows he likes the way Auwal fucks him and the availability of his lower body but denigrates him as a person: ‘“You sweet, all your people sweet, but –/…. / And then he rolled off the bed, straightened himself with a haughty dignity, looked Auwal in the eyes, and said, “You are a fool.” And then, “Ewu Hausa.”’[14] The social humiliation is complete and is organised around how the different codes of sex and romance are conducted comparatively within and between classes seen as superior or inferior within a pre-determined hierarchy.

These differences in the conduct of pleasure, satisfaction and love often play between prescribed power differences that interact complexly and not in simple binaries. Thus for instance power difference are found in age differences but the direction in which powerlessness runs varies according to factors like class, income, gender and a lot of other issues which touch upon power, including the entitlement to exert governance over others. In ‘What The Singers Say About Love’ it is clear that heteronormativity has always, if silently, allowed men to claim the hegemonic power of heterosexual men (varying around other factors of course) by being precise about what constituted the domains in which their participation was gay – by not kissing for instance or ‘sucking dick’ themselves though like ‘terribly cute Basil who had a girlfriend and said he wasn’t gay but loved getting his dick sucked by me but would never suck dick himself because, hey, he wasn’t gay’.[15]

Another characteristic of these stories however is their deep desire to see sex and love between men in a context wherein women too have varying roles, such as wives (‘The Dreamer’s Litany ‘), mothers (‘Mother’s Love’) and sisters (‘Where the Heart Sleeps’).There is great beauty and truth in the handling of this strand in many stories, where no there is no attempt to stereotype female responses, except where the woman has introjected a stereotype for herself. The learning done by Chikelu’s elderly mother in ‘Mother’s Love’ extends to her understanding that she failed to return her son’s love for her out of fear of contradicting an ideal in how she wanted to see herself and leaves open the chance that she acts to redeem her earlier actions based on feeling ‘so conflicted in her love of him’.[16] There is too much to say for me to do it justice, and besides I would prefer to hear women first say what their response might be before confirming that to me it all rings beautifully true and does not fail women as persons.

In a sense, I think the quotation from an interview in my title shows that Ifeakandu equates his queer experience and his desire, even from early youth with acts of cognitive, emotional and sensuous creation and as substitutes for what is merely given to people comfortably identifying as heterosexual in a heteronormative environment:

But it was boys who made my heart go wild. Boys were incredibly beautiful to me, not in the way that girls were—girls were beautiful in factual ways: fine girl. Boys, I wanted to hold. Soon, I began to write stories that satisfied this longing, especially as I began allowing myself freedom to be with, and think of, boys. Representing that love was my way of perhaps participating in something my heterosexual peers enjoyed without second thoughts.[17]

Sex becomes something experienced for Ifeakandu in the recreation (play and creativity) of writing and feeling the separate if sometimes semi-conjoined domains of love and sex between men. As a result we feel it speak quite grittily of each separated pleasure or satisfaction and the distance each is from something whole. It is gritty in its realism because not primarily motivated by an ideology like that of romantic love inherited from old traditions in writing but it is also wildly transgressive – breaking down boundaries that are often erected to protect such things from sight, hearing or touch, even in desire. And I think there is in this collection of stories the sense of a world that only makes sense because it contains men who love and / or have sex with men as part of its weave – a surprisingly large part I suppose for some.

It’s a huge world in these stories despite the different locales across Nigeria, but there is also a unity and comprehensibility and wholeness to that world, though we see it only in fragments ranging from the public to the most interior and private space. One reason for this is the omnipresence of the seasonal Harmattan wind, and season, which has some effect on all of the characters in each story. One beautiful example is Auwal’s memory of first falling in love with Idris, a lower class man like himself, whose love he loses whilst pursuing the Chief in ‘The Dreamer’s Litany’, whose body he first tasted as an accident of Harmattan:

A cold Friday after prayers, it was harmattan season, the wind rude and nefarious. If Auwal had not complained about the weather, Idris perhaps would not have driven his father’s car to Sabon Gari to buy a bottle of Rémy Martin, which they drank in the car, passing the bottle, the windows rolled up and the speakers blaring the song of the season. They sang together, No one be like you, their heads getting lighter and lighter, their faces drawing closer and closer. … At the motor park, the car’s lights turned off, the two of them nestled together in the back seat, Auwal thought for the first time, listening to Idris sleep, that he was in love.

There is imaginative building here that turns memory into ongoing desire and builds it out of recognisable material and physical bricks of local places and temporal recurrences of the local geography like seasons and weather. In the book the same places recur as people travel between them, with their full meaning like the commercial and deracinated Sabon Gari. And names too recur for minor characters between stories – such as Dave for instance, at the margin of many stories and always sexually available to other men. There is no reason these are the same people. The names are common enough but their repetition has a familiarising effect across the stories. But these are marginal effects. They need to be because the world has to seem the same in order the more to emphasise the differences in the kinds of persons, relationships and networks encountered in each story.

And there I want to leave this book but I will revisit it, for in part this blog is a preview of seeing Ifeakandu at Edinburgh Book Festival interviewed by Colm Tóibín. I am awaiting this with great expectations for these writers span generations in responsible queer writing and I can trust the elder writer to ask the right kind of questions of the younger, and invite such from his audience. I will refer back after the event. Meanwhile if you can’t get to Edinburgh (still tickets left) then read the book anyway. It is a treasure in any kind of writing – in queer literature it constitutes a turning point.

All the best

Steve

ADDENDUM following interview with Colm Tóibín:

This event felt very special despite the fact Ifeakandu spoke from USA via Zoom. Perhaps this is so because Tóibín and he are both consummate writers, interested in their craft and the minutiae of the technique of writing, down to the semantic issues involved in the choices of words and syntactic structure of sentences, as well as the larger issues of the design of storytelling frameworks. Tóibín told the audience that the fact that he was excited to talk to this debut author was not only because of the innovatory practices and mastery of storytelling paradigms both at the micro and macro levels in his technique. He felt too that this was a significant moment in the development of storytelling originating in Africa – and that this is indeed was why he had been invited to do this task by Damon Galgut. The third reason however was the fascination with how the queer love-story could be told and how this example solved problems in ways Tóibín was only just discovering – in his latest novel based on Thomas Mann’s life-story, The Magician, about which I have already blogged (see this link).

The exploration of technique by Tóibín was in detail. About how a short story writer deals with sharing the past history of his characters and the effects of conventional practices of introducing such histories as a matter of convention that may or may not work to enhance the effects of the story. The conversation was at a high level and educated us about the act of writing and the act of realizing the deep structures buried in queer love stories – structures at the level of social power and enacted by variations between different ‘languages’ in Nigeria and within the the use of the English language. Many stories were visited in this way to illustrate the superb handling of power differences and the wonder of this new writer.

This was a tremendous occasion. I loved it.

[1] Arinze Ifeakandu in an interview with Viviane Eng in Vivian Eng (2022) ‘The PEN Ten: An interview with Arinze Ifeakandu (June 16, 2022) Available online at: https://pen.org/the-pen-ten-an-interview-with-arinze-ifeakandu/

[2] Steve Bamlett blog is available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/06/12/who-taught-them-to-hide-they-never-wondered-they-were-only-curious-fingers-in-the-dark-you-like-it-somadina-said-not-in-a-voice-that-he-would-use-with-the-girls-and-women-years-away-he/

[3]Ifeakandu in an Interview by Ucheoma Onwutuebe(2022) in ‘Words Without Borders’ (online) available at: https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2022-06/an-interview-with-arinze-ifeakandu/

[4] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 27) ‘Happy Is a Doing Word’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 25 – 44.

[5] Anne-Christine d’Adesky (2019) ‘On a Progressive Platform for New African Literature’ in Literary Hub (online) Available at: https://lithub.com/on-a-progressive-platform-for-new-african-literature/

[6] Cited in Kelechi Njoku (2017) Review of Arinze Ifeakandu’s “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things” in Brittle Paper [March 19, 2017] (online). Available at: https://brittlepaper.com/2017/05/portrait-gods-gorgeous-children-review-arinze-ifeakandus-caine-prize-story-kelechi-njoku/. The sentence appears in Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 72) ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 67 – 87.

[7] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 83) ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’ op.cit.

[8] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 107) ‘Alo̗bam’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 89 – 112.

[9] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 137) ‘What The Singers Say About Love’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 131 – 168.

[10] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 118) ‘Good Intentions’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 113 – 130

[11] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 4) ‘The Dreamer’s Litany’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1 – 24

[12] Ibid: 10f.

[13] Ibid: 23

[14] Ibid: 24

[15] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 136) ‘What The Singers Say About Love’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 131 – 168

[16] Arinze Ifeakandu (2022: 203) ‘Mother’s Love’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 179 – 203

[17] Arinze Ifeakandu in an interview with Viviane Eng in Vivian Eng (2022) ‘The PEN Ten: An interview with Arinze Ifeakandu (June 16, 2022) Available online at: https://pen.org/the-pen-ten-an-interview-with-arinze-ifeakandu/

One thought on “Arinze Ifeakandu describes the discovery of his amative preferences when he was ‘a little boy’ thus: ‘But it was boys who made my heart go wild. Boys were incredibly beautiful to me, not in the way that girls were—… Boys, I wanted to hold. Soon, I began to write stories that satisfied this longing, especially as I began allowing myself freedom to be with, and think of, boys. Representing that love was my way of perhaps participating in something my heterosexual peers enjoyed without second thoughts’. This blog reflects on Arinze Ifeakandu’s (2022) ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’ and previews an interview of him with Colm Tóibín on the 24th August 2022.”