‘The rattling in my head began to fade. It would return, of course, … but I grew better at recognising it for what it was: a need to stop and admire the view’.[1] This blog reflects on why we sometimes might need the differentiated paces of the semi-graphic novel to get made. It uses an excellent example by Lizzy Stewart (2022) ‘Alison’ London, Serpent’s Tail, Profile Books.

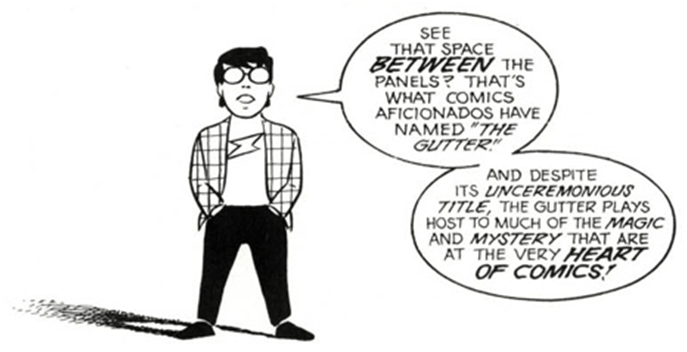

Figure 1:

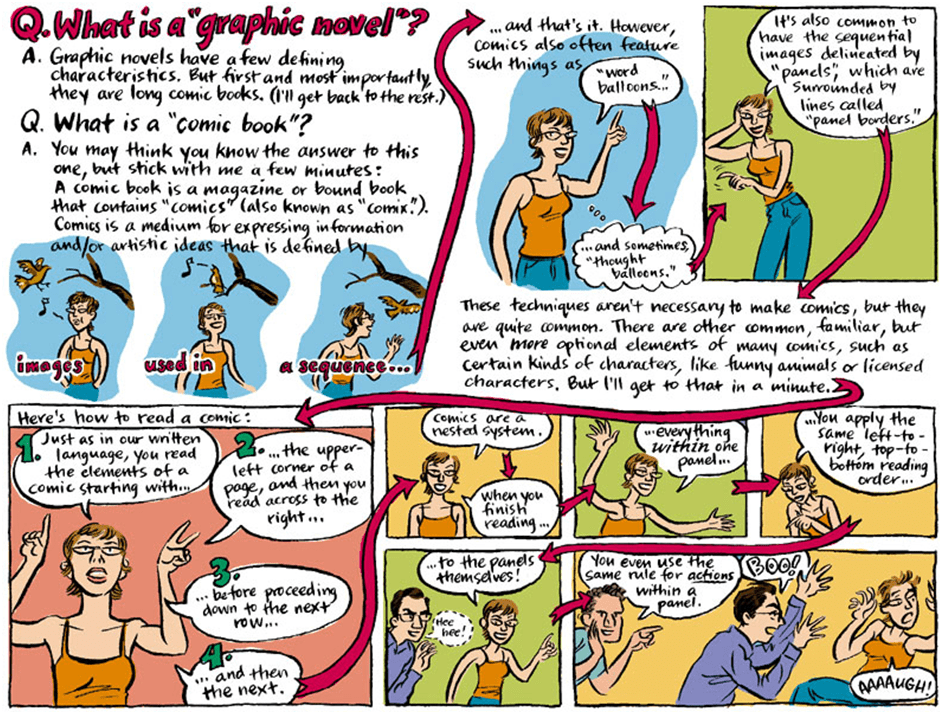

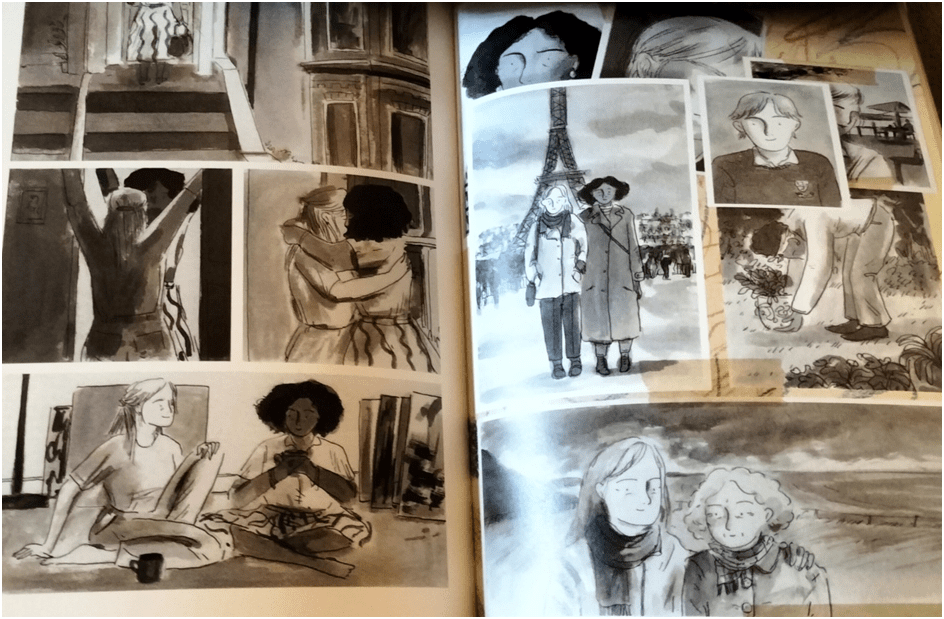

Purists of the graphic novel might dislike Lizzy Stewart’s Alison because it very often uses whole pages of text to tell its story and, at other times abandons the use of pages of panels with intervening gutters between each panel for a format in which a single illustration or panel gets hemmed in by text. Compare for instance these openings and single pages of the book, which give some idea why. Although the techniques exclusive to graphic novels appear here, there are also pages in which the text merely wraps around a panel in the manner of any word-processed document using graphic illustrations of its content. This may be why Stewart herself sometimes refers to it as ‘an illustrated novel’. Of course, before discussion it helps to have some vocabulary that isn’t necessarily needed for novels in typed text alone. The word ‘gutter’ for instance can be useful. There are beautiful graphic accounts of this terminology available on a website designed for that purpose: named simply Getting Graphic: Using Graphic Novels in the Language Arts Classroom. It is available from this link and the one above. Here is, for instance, its explanation of the term ‘gutter’, as used specifically with comic magazines or graphic novels, which are sometimes interchangeable terms – although ‘comic’ may not refer to something humorous.

Figure 2:

And, one better still is this graphic consisting of panels of various kinds, balloons for text that is supposed to voiced (or thought) of various kinds with gutters. It illustrates the conventional Western reading sequence of these novels / comics also.

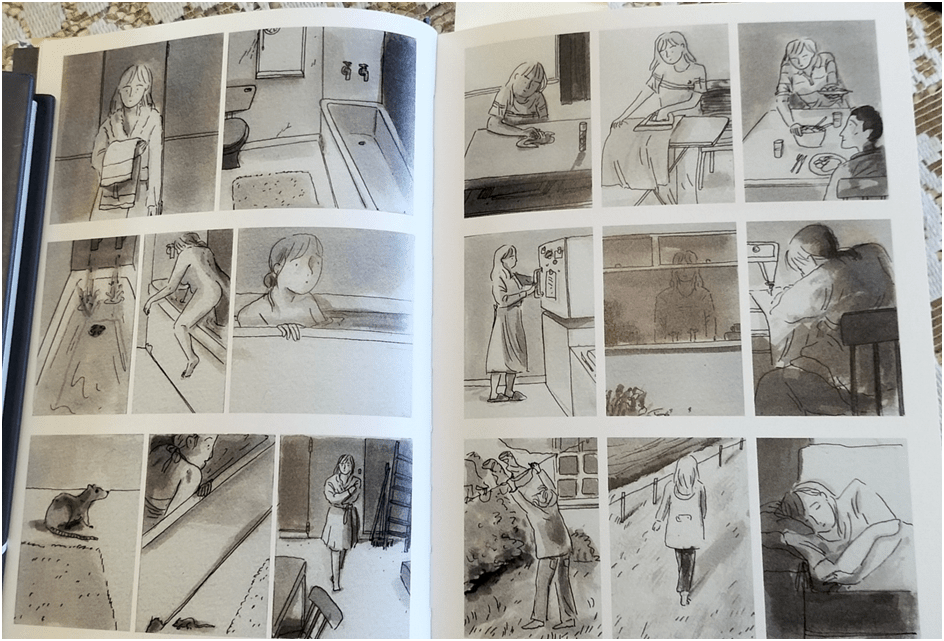

Figure 3:

In Alison the effects on the whole are, in the main, at first simple ones. However, even these emphasise the effects that varying from that simplicity has in the storytelling. And sometimes an apparent simple layout itself has variations that create effects of on a reader’s pace or concentration on an action. See, for instance, how we feel the self-consciousness of Alison, the central character in the first page of this opening than the second. Though the panels are sequenced regularly, the panel size varies on the first page such that we linger over those moments in which time expands for Alison as a result of her relative lack of business and the hypervigilance that explains why she notices the mouse (rat?) on the bathroom floor that appears to find access through the wall of the bath. The second line of the first page like the third has three panels but they are irregular in size, with the larger one reserved for her actually being in the bath, alert to noise and the presence of another life in a supposedly private space. How different from the second page where the monotony of her domestic work day folds into a sequence of regular and routine tasks, where the gaze of another on her – very clearly evoked on the first page though but a mouse it intrudes as does the viewer on Alison’s naked state. The central panel on the second page because it emphasises the relative opacity of the window to her kitchen suddenly brings our role of voyeur into focus again but now merely because of its central position on the page than pacing differences caused by spatial differentiations of panels.

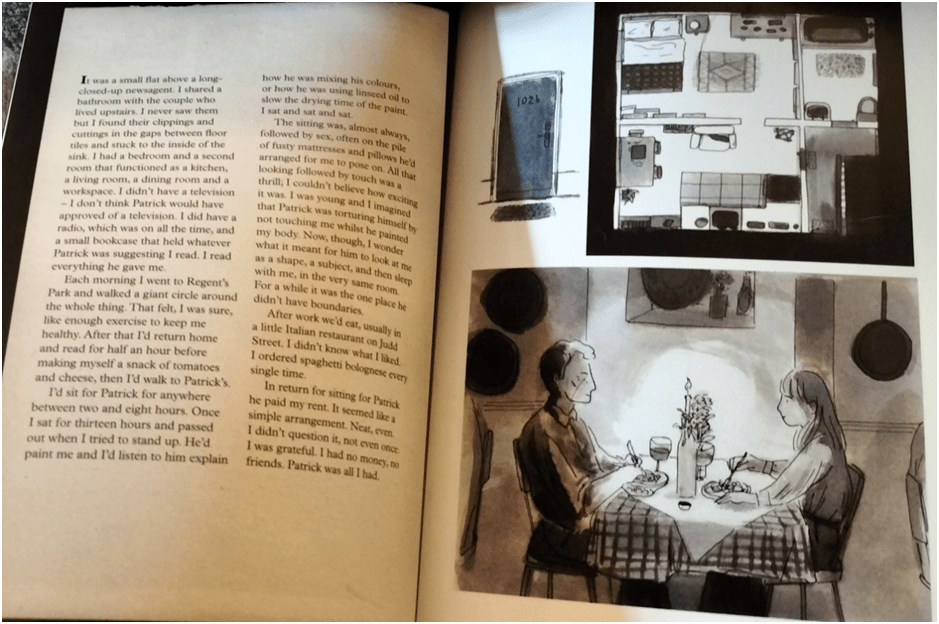

Figure 4:

We may be hard to convince that an effect of perceived soundlessness is created here just because there are no speech, sound or thought bubbles. I think that is because we lose the somatic sensations of mouthing elicited by words, especially when visually portrayed mouths are its source. We might intuit thought in Alison but what we notice most is that there is no space given to either talk or thought in this opening (Pages 6-7), so that we feel the preternatural quiet of her day. It conveys a busy solitude to compare with the static solitude of the full page picture that follows it (p. 8) with a single line: ‘But I was bored and I was lonely’ seen on the outside left of the collage below (Figure 5). Once the pace is changed, Alison is left alone with only space around her being filled with the meaning revealed in text. The view of the hills and beach, so beautifully drawn and captured, is not beautiful for her but merely empty. I will however return to the analysis of this page later in the blog.

We know that she is oblivious to the external beauty of the view here because Alison’s thought emerges in text that links her lonely moments on the cliff to the dull lack of communication in the wordless picture that follows on the next page that is necessarily surrounded by text explanatory of the silence. We are only told about this but also shown in the graphic panel on page 9. In that picture Andrew is just about to speak, but is not yet speaking for he tentatively gestures for Alison’s attention. The text tells of the unvoiced thought of the pair, which silence Andrew breaks with his suggestion of a hobby

Figure 5:

Compare a similar technique in terms of the pacing of the viewer’s reading of pictures to that of the pages covering Alison’s domestic day with the page on the right above. It displays a moment of human interaction, which at this point looks merely conventional, though it will be life-changing for Alison. Its conventional nature explains the regularly sequenced and sized panels . However, the contrasting significant drama involved (for this is the start of an affair) is conveyed by shifts of point of view and focus that is made busy with voiced sound and the suspicious look at the librarian at their creation of a non-conventional privacy in which public flirting is occurring. No doubt too the librarian feels condemned as part of the ‘this dreary little place’ (and what could be more dreary than stamping books whilst one’s ‘customers’ deliberately exclude you from the conversation) within which Alison attracts a strange man’s interest.

In the rest of the novel the pace of change in Alison’s life leads to many variations between the amount of text, the relative number and relative size changes of panels on each page and between and across single openings. The use of letters and postcards ensure the amount of geographical space involved too continually enlarges with the potentials of her life and art. Sometimes the effects change the relation of plain text pages with the use of technique from the graphic novel applied to those pages. Here in Figure 6 is a subtle effect that my photograph may not sufficiently capture, but which I explain below:

Figure 6:

The text on page 32 is placed on an off-colour page that reproduces one torn from a pad – even down to the sticky remnants on its top. It is a picture then of text and is framed as a panel in black margins (poorly reproduced in my photograph), giving the reader a sense of it being a found note contemporary to the action rather than part of a retrospective narrative, which it also is. These effects of movement between the time of which we are told and the time to which this is a flashback are very subtle. Moreover the black frame of the page panel makes this imaged text rhyme visually with a black framed panel facing it which is a ground plan of the ‘small flat’ into which Alison has been moved by Patrick.

In Figure 6, the black frame in each case hints to the reader of the imprisoned constriction we know that Alison will eventually feel in this flat dominated by Patrick’s view of women, art and life as a commodity manufactured by him for his own self-image. Alison lives there, it seems, as his ‘mistress’ (or at least so it seems to us, though his ‘wife’ is not a woman but his very selfish conception of his role as the Artist). It seems too that Patrick’s oily narcissistic readings of his relationships feed off his belief that women can be persuaded to live in romantic dreams nourished by him from a substantial income in art that sells. The dream is belied by the ‘clippings and cuttings’ (from the body parts of upstairs neighbours) ‘in the ‘gaps between floor tiles’ in the flat’s shared bathroom. Of course, this is also a nuanced narration of the relationship and Patrick is more than the simple Lothario he seems. Stewart’s picture of their meals together in an Italian restaurant above show a shared glow between them (not just made by candles), in which both of them believe, at least at the moment and outside the grim door (pictured above of flat-cum-prison-cell 1026).

This page also begins to show the features of a diary of mementoes from the story – a technique that contrasts the contemporary nature aped by the record of past events that are, in fact, being recalled. This too has a narrative subtlety for it conveys the excitement of the time of collection (especially later tickets saved from visited events in Paris and elsewhere) while making us aware that kept mementoes sometimes change their meaning with new interpretations of those events emerging with time and the processes of change within persons and between them in their relationships. Look, for instance, at the beautiful opening below.

Figure 7:

Although page 132 is a relatively straightforward graphic novel narration, if with significant pane size variations such as the drama of the meeting between Alison and her lover and artistic colleague (whatever the relationship they are. unlike that relationship with Patrick, equals) Tessa Effiong, a sculptor. Facing it is a series of frames aping photographs, together with signs of the Sellotape that sticks them onto a paper backing. The backing itself is a yellow sheet bearing coloured pastel shadings and doodles that shows it as once the drawing paper on which an illustrative artist practiced her colour combinations. The photographs clearly come from different parts of the story but show her father (in the garden), her mother (presumably after their new understanding has been established because they look comfortable with each other), Andrew, her beloved nephew and Tessa and Alison arm in arm in Paris. The latter overlays separate pictures of each woman, showing without telling the change of their relationship into mature love. Nothing could show that Alison’s life has become enriched and nuanced with almost everyone who matters in her life, though Patrick is now history and Patrick will soon die.

We should consider too how the narrative begins to employ colour, in some panels to demonstrate the new energy of Alison’s vision as a person and artist. The latter melds with the project as it must seem to Lizzy Stewart, as a vehicle for her finest art, and to the reader’s need to see, feel and sense life in pictures in a much richer way. Some of the fine ones are viewable in Figure 1 above. The acme of this trend is the beautiful showcase illustration of Alison, in her colourful and tasteful 60s, sitting in front of a white gallery wall showing a retrospective of her pictures (although somewhat eccentrically hung, if this is meant to show a true contemporary gallery). I cannot bring myself to reproduce this, because it alone is worth the cost of the book. It is meant to represent a show called ‘Work Space’ and it appears as a full opening of pages 166- 167, though the pages aren’t numbered per se.

That Alison’s work life matches with her newly enriched home life is seen in a beautiful opening in Figure 8 below, which shows Alison’s life opening out in contemporary letters (written for her by Stewart and bearing coloured thumb marks to indicate her new life as an artist), the key to her own new flat, a programme for a Beginners exhibition with Tessa and others and her identity-card from her new job as an art teacher:

Figure 8:

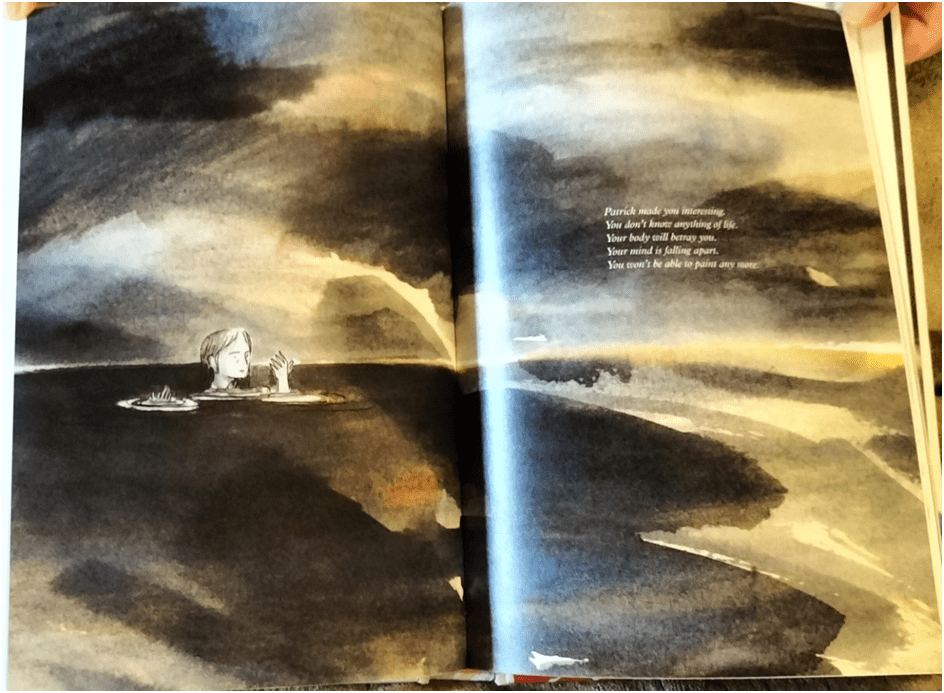

But there are even more important effects created within the narrative. In order to justify that statement I want to look at a case in which an imaginary scene is used to convey the internal landscapes of Alison’s unpleasant and frightening moods and fears during the period of her psychological depression. It is a full colour opening with no margins or publishers’ conventions such as pagination numbers and conveys to me the infinite extent of space that depression appears to open out to threaten its victim. Depression is I suppose is what colours the opening with such darkness, though it is not the sole mood indicator. It illustrates Alison’s most negative, but now hegemonic, thoughts about herself and her future as printed white text over a dark cloudy patch of the screen.

Patrick made you interesting.

You don’t know anything of life.

Your body will betray you.

Your mind is falling apart

You won’t be able to paint any more.

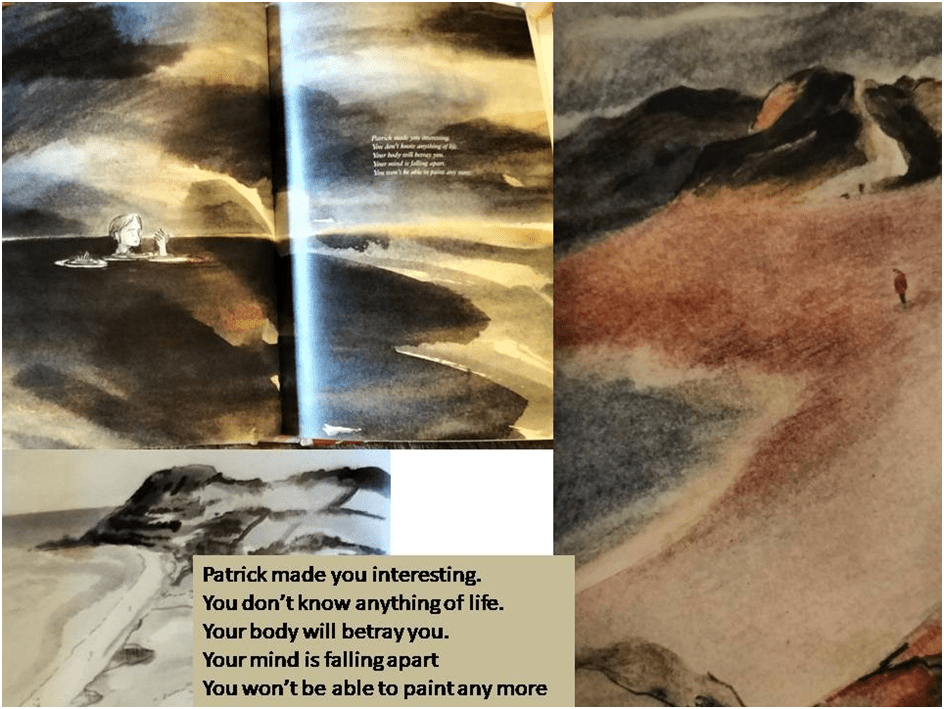

We can see it in Figure 9. But, before doing so, it’s worth considering whether this is simple mood painting, for the dark is flecked with underlying blue. Though made of colour inks as book illustrations must be it seems also to ape the layering and scraping off method of ‘painterly’ oils (the method say of Frank Auerbach though objects are not as abstracted).

Figure 9:

Moreover, as a narrative element, this picture runs much deeper to Alison’s psyche than the thin and deliberately cartoon-like caricature of her within it represents. For this is rich painterly Alison seeing the stranded thin-drawn-figure obsessed Alison of the past. In my mind we are invited to slow our pace completely and just gaze at the beauty of this opening (much dimmed in my photograph) for a considerable duration of time. If we do memory and imagination will play tricks i opening out glimmers of something beyond imperious depression.

In my view, one of the reasons for this is that the landscape behind the darkness of weather-like atmosphere is recognisably the same, with the same structure of mountains and beach, as that we saw when we saw her ‘bored’ and ‘lonely’ on page 8 of Figure 5, which I reproduce again in Figure 10. Look at them together in Figure 10 below, which also contains a colour recurrence of the same beach already seen in Figure 1.

Figure 10:

My admiration for this book is built in a very large part from this beautiful recurrence but not from that alone for the whole is much more masterly than it will seem to others. For one effect of the full panel on page 8 I did not mention at all above is the fact that it is a beautiful drawing, of Alison’s home coastal landscape in Bridport, Dorset. We are persuaded by text speaking of her boredom and loneliness when we first confront it that this landscape illustrates merely the lonely boring space of Alison’s lacklustre conventional marriage with school-chum Andrew. But, if we love pictures, we also see something in the view in which to linger, slow down our reading pace and explore, that is conveyed subtly in shades of grey and hatching passages which capture nearby grass, distant vistas shaded by high clouds and distance, cliffs, sturdy rock and fields melting into distance. As a reader I lingered here, when I looked again began to see Alison (contrary to the text) admiring the view rather than being squashed by it. She is admiring the view rather than being it. Of course, Alison might not see this on page 8 is because it is a view to which she is habituated.

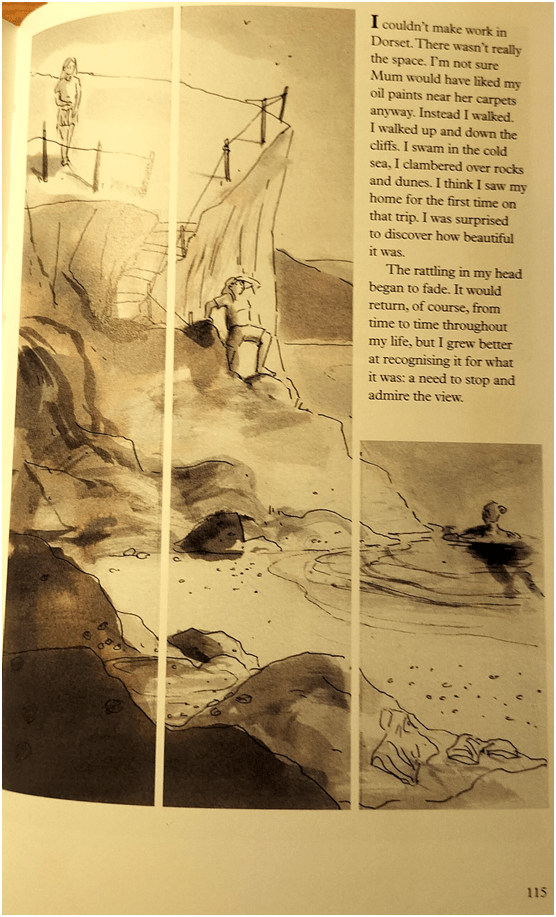

The beauty of the scene though begins to be demonstrated much more fully on page 27, where the beach and hills are seen in colour. Of course there is a red-coated lonely figure on it, which may be Alison, bidding farewell to a scene in which she has only just begun to notice its beauty in a rich and lively way. The reader, however, is inclined to linger on that page absorbing it and contrasting it with the text opposite, framed in the richest deepest black telling of the duration of the marriage break-up but not referencing this scene. By the time we see the scene again (as in Figure 9) it is covered over in gloom, though blue skies (bright blue paint it seems layered over by black and grey paint) underlies the gloom. The recurrence of the picture indicates the scene to which Alison must and will return – mending her and her parents’ relationships to her and each other, being with her father too before his oncoming death. And when she goes back (and here’s Stewart’s brilliant narrative technique), exploring that coast over three frames on page 115 (figure 11) and swimming in (rather than being lost in as on pages 108-9) the water of the beach rather than feeling drowned by it as in page 108 (figure 9), she says (as cited in my title): ‘The rattling in my head began to fade. It would return, of course, … but I grew better at recognising it for what it was: a need to stop and admire the view’.[2]

Figure 11:

The rattling is a symptom of her anxious depression but also signals a life not sorted out or which has run adrift, but it is also the pace of reading some people think proper to graphic novels. What the illustrator and artist, Lizzie and Alison, here tells you (for I think at this point they are one and the same) is that we all need sometimes to lose the business of our lives – play down the endless motion through its sequences and ‘admire the view’. A reader who will truly enjoy the art in graphic novels will DO just that. Go back to those splendid openings in the book and just ‘admire the view’, particularly that one, which I do not reproduce in its final opening of the Work Space exhibition.

Have a read. Do that especially if you do not know if you like graphic novel. For more blogs on the principle of graphic novels try these using links:

On Anne Carson’s The Trojan Women.

On a modern USA version of Dante’s Inferno

All the best

[1] Lizzy Stewart (2022: 115) Alison London, Profile Books

[2] Ibid: 115