‘Sometimes I would wake then, not knowing how the dream ended. Other times I would see a diver near the surface, his silhouette like an angel a mile above us, and then I noticed or knew somehow that it was myself, or some future version of myself that had come to tell me something, to save me, perhaps to tell me a secret, to assure me that all this would mean something in the end’.[1] This blog reflects on a recent memoir by poet Seán Hewitt (2022) ‘All Down Darkness Wide’ London, Jonathan Cape.

Other blogs by me on Seán Hewitt are available – see list at end (click link).

This year sometime Seán Hewitt was or will be 32. It is a young age from which to write a memoir and I suppose you approach a book of a man that age with trepidation that it might need to prove the point that there is enough to say about a life that has only reached thus far. But it is a mistake, though one I frankly admit to have made, to think like that for something like writing our life is a continual project in which we are all engaged: a process wherein memory, reflection, imagination and narrative reconstructions feed into something projected into our future life as hope, wish fulfilments and mitigated catastrophic expectations of whether it will continue, and how it might end. The end (or ends) I speak of here is (or are) not necessarily considered in these mental and somatic amalgams of sensation, emotion and thought as one event only but sometimes as multiple anticipatory forms of making something complete that feels as if it not yet finished, which might indeed be an event but equally be a sense of closure that cannot easily be fitted into a schedule.

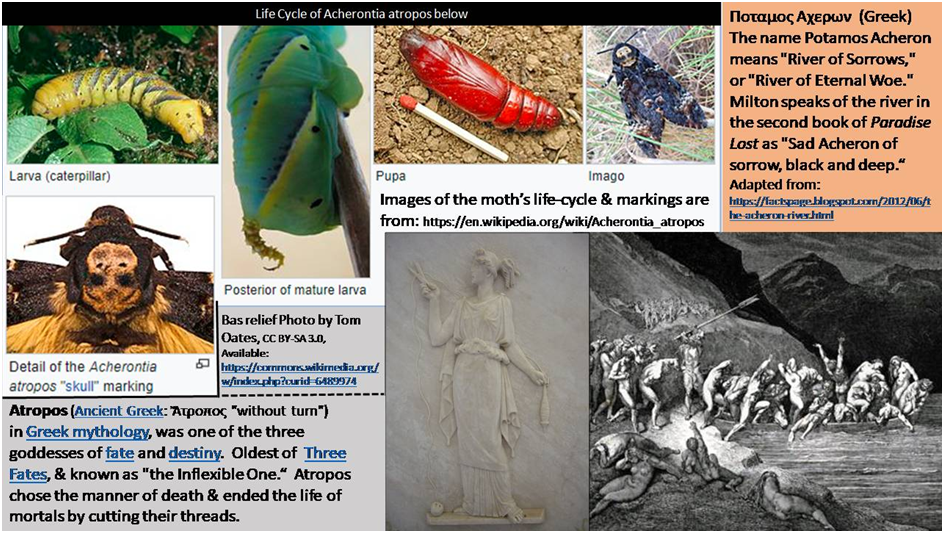

The end of this book is an example of what I have tried to describe above, which performs musical magic with a name of a caterpillar (or its imago – a term in which both beautiful meanings seem intended), feeding on nightshade, till it became time to ‘refigure itself’: Acherontia atropos, the transliterated Greek name of the African death’s-head hawkmoth. The mythological associations of its name are unfolded in Hewitt’s prose together with a source for his particular use of the mythological figure of Acheron (‘looked up’ on his Smartphone) from Virgil’s Aeneid, book 8: ‘flectere si nequeo supros, Acherontia movebo’.

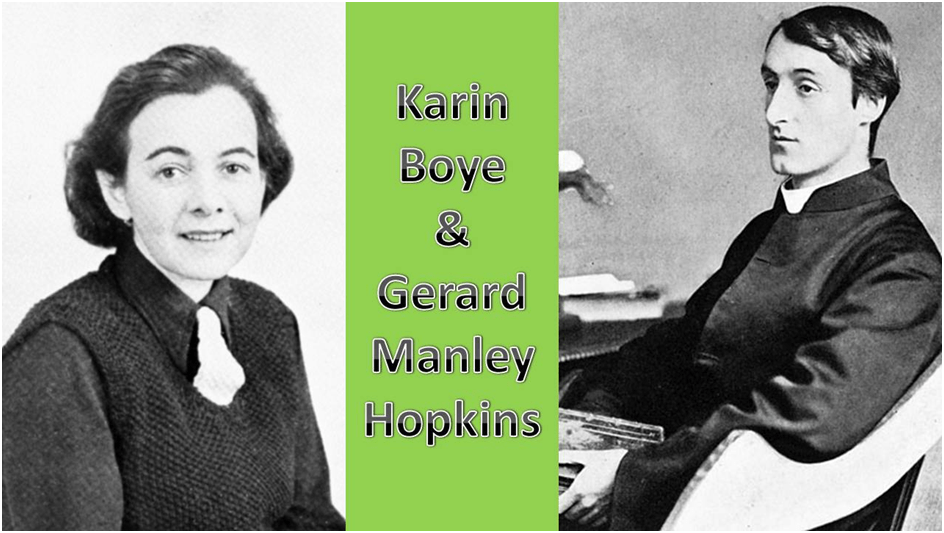

As he tussles with the meaning of that line of Latin verse (because he ‘didn’t know which version’ of the translations he searched for (again on his phone) was ‘closer’), he recalls his first real male lover, Jack, a classical PhD scholar whilst Seán was an undergraduate. Jack was not only his lover but was remembered with ‘all his dictionaries and glossaries and grammars stacked along his shelf in that room in Cambridge’. All these paths in and through alien, and in this case dead, languages are continually complicating Seán’s memories of the beginnings and the ends of his life with his lovers. With the lover in the story who matters most this book, the Swedish young man Elias, Seán translates the poetry of a lesbian Swedish poet, Karin Boye, about love and the Siren call of death (such raw subjects in their own relationship). Seán and Elias are continually confronting the boundaries of their feelings as they try to love themselves and each other; learning theses feelings are intermeshed with continual misunderstandings pertinent to communication in all spoken and written language. These misunderstandings cannot be reduced only to the fact that Seán primarily spoke English and Elias Swedish:

In simplifying my speech, I worried that I was simplifying the ways in which he could know of me, or that I was simplifying the ways in which he could know me. No doubt he was doing the same, but rather than simplifying himself in his own language, he was simplifying himself in mine. What he didn’t have a word for, or the grammar for, had to be left unsaid. Maybe part of the problem, looking back, was here, in the things we lost between each other, in our failed sentences, in the things we lost the courage to say. In easier times, there was less at stake. What did it matter if a few things were lost, when we had so much in store? But soon the space between us became dark and impassable, and in the aftermath we had lost so much of ourselves that we hadn’t the energy to try it all again.[2]

All communication requires a trust that if ‘a few things are lost’ in the gaps and impasses in the exchanges between us, it doesn’t really ‘matter’. Because in social, amative or sexual relationships, when things are ‘easier’, it is precisely because our belief in each other is never being tested experimentally by what we say to each other in language. Those times are easier because other matter fills the gaps in our communion, such as the touch of bodies or an intimacy we call ‘love’ that is ‘magnified by the fact we travelled alone together, ate every meal together and slept together every night’, as was the case for these young men when they met in South America.[3] When times are difficult there is a premium on what we might be losing as we exchange words and sentences whilst communion between ourselves is virtually impossible when the ‘space between us became dark and impassable’. That ‘space’ is variously conveyed through the novel; most beautifully in the spanning of cosmic space wherein ‘a new universe of possibilities I had never considered before reeled and span open like black holes’, a space already imagined for Seán by Gerard Manley Hopkins, but not fulfilled as for the latter by any ‘piercèd lights’, in a ‘cold, unforgiving openness, an endless depth of dark above me’.[4]

It is precisely those moments when our humanity is challenged by the pain or sorrow of one or both of us that the world and hope for its future looks most ‘dark’. It is dark not only in its mental and emotional associations but in terms of its comprehensibility, for ‘dark’ is usually a term we use to reference that which is hard to understand (suggesting what is shadowed, and obscure and with no escape into the light of clarity possible in the here and now). It is the metaphor used by St. Paul in the King James’s version of the New Testament: ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known’.[5] And this is why the cluster of dark (in all senses of the word) associations of the Acherontia atropos matter so much at the end of the novel. This moth associates with the end of life, especially ones cut too short (ended before hope has spun its expectations of better).

In this book, the analogue for such lives in Seán’s life-experience are not only the obvious ones of the suicide of Jack, Karin Boye and the attempted one of Elias. These are hard to understand turns of fate that sometimes terminate the flow of these beautiful queer persons down the river Acheron (of pain and sorrow). But Atropos also cuts narrative threads by burying lives under its river of the life-denying (LBGTQ+ people in particular) whether suicide is completed (as with Jack) or not (by Elias) or by lives ended merely because not lived in any way that can be called ‘living’. These ideas of lives lost resonate and interact. The thread Atropos cuts for Elias is of his narrative interest to the reader and that, and its personal living future-directed emotional significance, to Seán – it is the last of the partings between them that, as with others, is really about Seán losing ‘a newly discovered part of myself behind’ (a phrase used of the more trivial parting between them at the end of their stay in South America where they met).[6] It is the apparent metaphorical temporary or permanent ‘loss’ of one of the possibilities of becoming this or that kind of man that Seán might have been fated to be.

Thus at the end of the novel, Seán faces not a lost lover facing him across the space of time but a lost self, the child he once was, secure in his home but hiding from the rest of the world any desire of a romantic attachment that might be meaningful to him. Since being a child, he tells us, he had observed Atropos observing him – counting out the thread of his life but unsure it had any meaning because what would make his life romantically complete was hidden from him and others. The play in this paragraph with the word ‘hide’ takes many and beautiful forms (which recur throughout the novel) in which the complex desires of the young Seán for safety and security rather than fulfilment in the body of another outside his biological family motivate the hiding of his sexuality. Hiding becomes for the young queer child an ‘end’ in itself:

… I had felt the inflexible Fate watching. I had seen the end of the thread, held between her fingers. I didn’t know how long the thread was, but I had thought perhaps ten more years, or fifteen, was the best I could hope for. I say ‘hope’, because even though I was mimicking, even though I was hidden, and the hiding was crippling that fragile part of myself I knew to be true, I was also safe in my hiding. In my hiding, I was loved.[7]

This is a dark passage in every which way. It convolutes because words do not and cannot mean exactly what they might be thought to mean – words here such as ‘hope’, for instance, which the writer himself puts in quotation marks. The word is actually used of a hopeless child giving in to the wish he might have had for a long fulfilled sexual and amative life in return for present safety. It is the young gay child’s perception too, filtered through adult words and body-language, of the fate of so many gay young men heretofore – their slide into obscure mental instability or obscured shadowed lives out of the public gaze ‘caused’ by their need to hide forever the self they ‘knew to be true’ and, for some (too many), the choice of suicide before public shame. Indeed a beauty easy to miss in the novel is that the final paragraph of the novel is a musical riff on the theme of peeling an orange. For the first mention of this was that of Hassan at Cambridge, who had been part of the sexual triad with Seán and Jack.

As a boy, Hassan tells Seán, he was punished for ‘the effeminacy he showed in childhood’ by being made by his grandfather to eat the ‘bitter skin’ (‘husk and rind’) of oranges whose flesh was reserved for, once exposed, the grandfather alone. Once freed to Cambridge, Hasan whenever ‘he ate oranges’ would ‘keep the rind and burn it in the fireplace in his college room’.[8] And with this self-same ‘ritual’ Seán ends the novel, in despite of Atropos and Acheron, but he tells of the action with a subtly beautiful difference: ‘I unpeeled the orange in my hands, ribboning its thick hide into my palm. I … leant forward and threw the rinds of the fruit one by one in the fire’.[9]

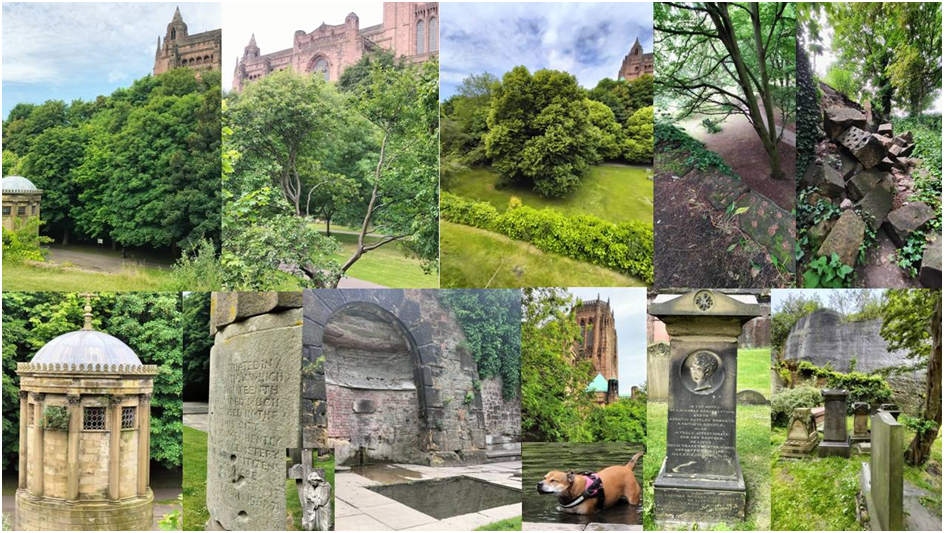

In the final parable of the orange–peeling, an author visually makes his own threads out of the surface of a once living thing – in that verbal invention ‘ribboning’. Ribboning is a verbal invention which turns inflexible Atropos unwinding her thread anew into an icon now in radical drag (at least in my eyes). But significantly, before being named as ‘rinds’, the skin of the orange is named a ‘thick hide’. The cognitive effect is subtle for what hides the orange is the bitter covering up of one’s fruit – hence being made to eat it is an apt punishment for an effeminate boy, a grandfather might be imagined to think. Now Seán is control and burns to naught those strands of lies hiding a truer self in its ribboned threads of false stories and narratives. It recalls the author’s account of his own growing up: ‘I tried to hide myself, not to give myself away’.[10] The shades of the hidden makes themselves known through partial revelations throughout the memoir, like the ghosts which also frequent the narrative. The most moving group of ghosts is of those which have died of AIDs in its first vicious onslaught, when HIV infection was untreatable. Feeling he may have become infected from sexual contact in the ancient quarry-cum-cemetery-cum-park of St. James in Liverpool, he imagines HIV coursing his blood:

My mind whirred and whirred madly over statistics and history, ancestry, all those men lining the corridors of wards, all those bleeping machines and frail, stick-thin corpses. Though I did not know them, their ghosts haunt me. …: I arrived into a world of ghosts, and owed a part of myself to them.[11]

Ghosts are a way of hiding but also of reasserting what is hidden, as we will see later but they darken life for most. As Elias falls into the darkest of depressions wherein he ‘slept for longer’ or ‘was sometimes harder to rouse’ so does the whole city of Gothenburg curling itself into foetal position for the cold Swedish winter: ‘The city itself had fallen into something like a blackout, as though everyone were in hiding. Everything slept for longer’.[12] But the use of hiding as a means of understanding the effect of societal disapproval of the sexually queer is where we find the submerged metaphor more, as occasioned by bodies (that ought to protect the individual like the organs of Church and State) becoming oppressors threatening to extirpate what will not change into its own ideal image or, at least, hide what raises its distaste. At the age of twenty Hewitt faced the reaction against equal marriage rights wherein the ‘old institutions I had hidden behind seemed to blaze in a final fury’.[13]

I don’t sense an essential indication of a ‘truer self’ revealed here under what ‘hides’ it however. What the end of the novel is about is eradicating the sense that the self needs to have a fixed or ‘end-state’ form at all. For selves are truly only ever emergent: ‘there is no ‘formed’, only forming; ongoing unfolding’, or indeed unpeeling what is inauthentic and hides self in the expectation of something juicier to be revealed.[14] It is this process of continual emergence which is the secret of this memoir and its wise embrace of life that includes, indeed in the full sense contains (holds back in one sense), deaths, ends that are beginnings, losses that are also, in the long duration, gains. It is a very Catholic Christian theme, even if a secular version, just as Seán Hewitt becomes a secular Gerard Manley Hopkins.

The foreshortening of the projected end of stories also plays a huge part in a brief memoir whose own ending becomes a kind of hymn to the classical Gods’ handmaiden of endings who has been in some sense exposed for her inflexibility and rigidity, like the Catholic Church over both equal marriage rights and the incarceration of what remains beautiful in Father Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poems, if not his sermons or the young priest who has cold sex with Seán after Elias has finally gone. Seán feels and grieves for the ending of his life under the protection of the Church (whether he was a believer or not): ‘crying for myself too – the world I was leaving behind, the safety of it, the sealed hypocritical life I was living and I couldn’t live any more. I was saying goodbye to the self I had prayed for, …’.[15] Ends are found even in the wild loving of which men are sometimes capable, that is ‘less restrained, less self-conscious, under the surface of their masculinity’: it takes place in a setting South American locals in Mocoa, Putamayo call ‘Fin del Mundo’ or ‘The End of the World’.[16]

We are used to ends that are beginnings and losses that are gains in poetry since T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets but they are embedded in myth too, Christian or otherwise; myths like those of metamorphoses of life and resurrection of bodies. It is in this mythical context that we should see the interest in the book in ‘the legacy of Hewitt’s Catholic upbringing’ which Michael Donkor wrongly claims is merely one of the book’s ‘quieter interests’.[17] The space in which those myths become owned by Seán is St. James Park Liverpool. I visited this park myself this year for the first time – and recorded that visit as part of a summary blog for which click here. The park was once a quarry for the stone to build the grandeur of slave-trade wealthy Liverpool, became a grand cemetery with fine descending runways for carriages and now is a public park in the shadow of the Anglican Cathedral holding ghosts of its past memories. These form part of a fantastic structure of natural and made terraces, features such as a spring well, statuary and a mausoleum, once including a statue to young Huskisson, the minister brought to his end by a train in the days of their early beginning.

It becomes in section I of the memoir a symbol of persons we see later in which the river of Acheron is already suggested and the poet gives up his body, for possession sexually or as a vehicle for the resumed life of the lost, forgotten, and the dead; including those lives prematurely ended. It is a moment where he becomes literally the Host of the body, the blood and the Holy Ghost, or Paraclete, which will appear again through the analogies between poet Hopkins’s love of both men AND, in the same sacred moment, Christ’s body: [18]

… Jack, Elias, all the others who had entered the darkness and had struggled to leave it. I cannot speak for the unheard sounds of those in the graves below. But for the man I met – for all of them – for that endlessly linking river, with all its nodes and tributaries, I can offer whatever of it my body still holds. In my mind, on my lips, in my heart. I stood in the darkness, under the long shadow of the cathedral, and lifted my thumb up to my forehead, my mouth, my chest, and left a bright stain of blood on each.[19]

This park appears on the first page of the memoir. And it, and the windowless Oratory standing above its entrance, becomes the very symbol of what is hidden (including the poverty of the great and rich city of Liverpool). The locked state of the Oratory provides a symbol of how, when ‘cast-iron locks’ are bolted fast, ‘it is easy for those who do not live with them to pretend that ghosts do not exist at all’. And thus whole populations (the poor and marginal and, I think, the gay men who haunt it at night) of Liverpool are locked up in honour of the riches of a bourgeoisie fat on slavery and now wage slavery.[20] It is the perfect image of how what seems lost has been ‘forgotten’ but which may seek to resurrect itself into life – something new from something old, something remembered from the forgotten, something gained from what is lost and something beginning we thought had seen its final end. It is amazing how I must seek for symbolic rhetoric to describe this facet of the memoir and, to be honest I was suspicious of Hewitt’s weighty rhetorical prose when I started the book: for instance this last sentence of his first paragraph reminded me not a little of the faux legendary of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (see it on my collage below).

Years ago, as the great homes of the city were pulled down stone by stone, the monuments of the proud families (monuments of terracotta and marble and bronze) were hoisted here and locked away, and so the wealth of the city – wrenched from far-off lands and furnished from blood – was hidden, and so forgotten.[21]

It’s that last phrase of Hewitt’s paragraph that seems to me so like Tolkien or did do so at first reading. But I forget perhaps that Hewitt is the first to identify his own stylistic lyricism and ‘poetic’ style and even to render it a joke, for instance the joke about the Swedish name for flipflops (Klippklacker).[22] Alternatively, in an earlier passage his lyrical pastoral effusion descriptive of sitting with Jack on a tree branch gets coarsened by language strictly ‘vulgar’ and inserted into comically paced narrative and dialogue that undercuts it; ‘he looked at me, half-joking: “Do you want to suck my dick?” / I pushed him in the arm and told him to fuck off …’.[23]

However, the turn to symbolism, and a certain weight in the prose that comes with that, is a strength in a story basically about ‘coming out’ for it allows Seán to embed his experience in these grand Wagnerian musical motifs that sing of the experience of flowing rivers, immersion in water and rebirth from it, even the Acheron of pain and sorrow. That is the river we contact in St. James, in the passage I have already quoted, but here it is again: ‘But for the man I met – for all of them – for that endlessly linking river, with all its nodes and tributaries, I can offer whatever of it my body still holds’. How else can endless meetings inspired by cruising St. James, and other Liverpool parks, or networking on Grindr, be turned into a symbol of baptismal renewal – the birth of a queer soul that had buried itself in order to ‘hide’. And significant meetings take part in real water (as at ‘The End of the World’ waterfall as I have already shown). Hopkins himself even sees his love of the bodies of many men, idealised as it might be, in a line that could have evoked Gloria Gaynor’s It’s Raining Men. As Seán naively, and surely tongue in cheek says, as he cites The Lantern Out of Doors, and eventually wondering if it referred to ‘men like him and like me … everything was hidden, kept down’:[24]

I … read it, wondering what it was I remembered, what Hopkins was trying to tell me. “Men go by me,” he wrote,

Whom either beauty bright

In mould or mind or what not else makes rare:

They rain against our much-thick and marsh air

Rich beams, till death and distance buys them quite.[25]

There are lakes and rivers aplenty in the memoir; ones in Sweden, for instance, such as the Säveån.[26] There are different versions of running water that is ‘an unearthly green’ that are confronted at Lourdes.[27] There is water in the poem Nocturnal by John Donne or in the tragic suicidal poetry of Karin Boye: including the word ‘“överflödad”, over-flooded’.[28] Metaphorically we have: ‘Time. Like a river, flowed quietly past us, never bearing us with it’.[29] Yet the most beautiful passages evoke scenes underwater, as parallel scenes speak of an Underworld, classical or infernal. The first unheeded warning of Elias’s later confrontation with the world of madness and sadness is with an underwater world when he tells Seán of one evening after drinks of how he felt and what he remembers of his swim near the waterfall:

… he told me how he could hear voices of the boys underwater, distorted, and the sounds of the moisture dripping from the palm fronds on to the surface, … He hear the voices inside the water, and the bubbling crashes of the stream and the grinding of the stones, and, lost in the echoes, briefly forgot himself. It was like being in a different world, he said, like being submerged in another dimension.[30]

This ghostly water in which disembodied voices distort one’s sense of the world cannot be given a meaning but they evoke so much about how the relation of self and the thing we recognise as a ‘real’ world has been disturbed, were something lost from our lives has not yet become recognisable as something gained or newly beginning but as a drowning, like baptism by full immersion, without a new life afterward. Likewise we are underwater in the citation in my title:

Sometimes I would wake then, not knowing how the dream ended. Other times I would see a diver near the surface, his silhouette like an angel a mile above us, and then I noticed or knew somehow that it was myself, or some future version of myself that had come to tell me something, to save me, perhaps to tell me a secret, to assure me that all this would mean something in the end.[31]

Again it is about selves, but about selves in communion, the old and new and has redemptive overtones – of the appearance of the Paraclete in the form of an angel or the Holy Ghost (or even a heron later) who will ‘save me’, that carries Pentecostal messages, unearthing things hidden from a secret other world and saying that things do not end until they come with meaning. They promise a completion that is also a goal in the hermeneutics of our self-understanding and understanding of others – a world where pain and sorrow in the river Acheron ‘mean something in the end’. And we should not forget that blood also is conceived of as a river and a ‘network’.[32]

Metaphors breed other metaphors. The blood, with its rhythmic pulse, is also a music we often fail to listen to or see, except in blood donation clinics where we might see a visualised metrical (in brief an iambic) poetry ‘the scarlet pouches of blood moving in iambs, the motion of their hearts externalised and made visible’. And music metaphors also come with warnings of a music repressed, in quoting Keats Ode on a Grecian Urn, for instance: ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter’.[33] Music echoes like the river metaphors do in this passage of counterpointed rhythms. It illustrates Jack’s silent progress to unheard sorrow and suicide and it is the music of queer men condemned to living hidden rather than face ‘tacit disdain’:[34]

With a haunting completion, those notes had played out, their minor undercurrent picked up, and played into prominence. I knew that music now. Its strain seemed to run through the lives of so many of the men I knew – a sort of counterpoint, shimmering in the background, rising and falling from the melody.[35]

The use of the term ‘completion’ (used professionally of ‘successful’ suicide’) rings hollowly here in a novel of different kinds of ending. In a church in Sweden during the dark night of their lack of communion, Elias and Seán hear music as ‘a symbol of hope, even if it were not the real thing’ but that might ‘masquerade long enough to matter’.[36]

Other metaphors matter too. I noticed binaries of closeted imprisonment and freedom, of light and dark, of the supernatural – particularly the myth of the doppelgänger – and of a spirit-driven weather. But the beauty of this memoir for me is not its style – as if this could be divorced from its meaningful goals in a work of art – but its valorisation of queer people as both communicating family (which not all biological families are as the memoir shows) and as a community. Here, for instance, is the wonderful discovery that an apparent dead-end outside the window of the young mens’ student flat is in fact the path to a ‘gay sauna’ trod by people of all social strata and type: ‘I would wave back and smile at them. An unlikely sort of kinship, between the quiet student and the drag queens and the twinks, but it was my first real sense of community’.[37]

This is a wonderful memoir. It is an innovative and necessary address to coming out stories that challenges the complacency of all images that are required to be a hundred per cent positive and to tell narratives in which cheerfulness is enforced rather than true well being and joy found. Read it. Although I read it only after completing my review thus far I found a similar understanding (and rejoiced in that) in Kate Kellaway’s review in The Observer. She says brilliantly:

It is about coming out in the widest sense – and that includes the outing of depression. It is about the disinterring, too, of the fears of his younger self. And while it adheres to faith of a kind, the stability of belief is not always available to Hewitt, a former Catholic – any more than it was to Hopkins.[38]

All the best

Steve

Other blogs by me on Seán Hewitt are available – (click appropriate link): On Lantern (2019); A reading of the poem 2. ‘Callery Pear’; 3. On Tongues of Fire (2020)

[1] Seán Hewitt (2022: 155) ‘All Down Darkness Wide’ London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Ibid: 157

[3] Ibid: 65

[4] Citing Hopkins, ibid: 91

[5] St Paul in I Corinthians chapter 13, verse 12.

[6] Ibid: 65

[7] Ibid: 228. ‘Inflexible’ is appropriate for Atropos for her name means ‘without turn’.

[8] Ibid: 45

[9] Ibid: 229

[10] Ibid: 119. My italics.

[11] Ibid: 9

[12] Ibid: 77

[13] Ibid: 129

[14] Ibid: 229

[15] Ibid: 128f.

[16] Ibid: 58, 57 respectively

[17]Michael Donkor (2022) ‘Enduring love’ in The Guardian (Saturday Supplement 23/07/22) page 62.

[18] See ibid: 213f.

[19] Ibid: 16

[20] Ibid: 4

[21] Ibid: 3

[22] Ibid: 63

[23] Ibid: 27

[24] Ibid; 31

[25] Hopkins cited ibid: 30

[26] Ibid: 162

[27] Ibid: 120

[28] Ibid: 206 & 160 respectively

[29] Ibid: 139

[30] Ibid: 59

[31] Seán Hewitt (2022: 155) ‘All Down Darkness Wide’ London, Jonathan Cape

[32] Ibid: 10

[33] Cited ibid: 16

[34] Ibid: 129

[35] Ibid: 46

[36] Ibid: 207

[37] Ibid: 70

[38] Kate Kellaway (2022) ‘Review’ (Sunday 10 July 22) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jul/10/all-down-darkness-wide-by-sean-hewitt-review-a-remarkable-memoir-of-love-and-sorrow-in-sweden

3 thoughts on “‘Sometimes I would wake then, not knowing how the dream ended. Other times I would see a diver near the surface, his silhouette like an angel a mile above us, and then I noticed or knew somehow that it was myself, or some future version of myself that had come to tell me something, to save me, perhaps to tell me a secret, to assure me that all this would mean something in the end’. This blog reflects on a recent memoir by poet Seán Hewitt (2022) ‘All Down Darkness Wide’”