In a Foreword to a book relating to an exhibition based on David Hockney’s stimulus to the academic world to revise its boundaries, in the history of art at least, Alan Bookbinder and Luke Syson say that the ‘project demonstrates that the phenomena of seeing and experiencing are germane to both science and art’. They go on to claim it represents ‘easing’ between these academic disciplinary borders that will, by ‘cross-pollination of ideas and innovation () help us all look differently at the world we inhabit’.[1] This blog reflects on a much needed attempt to examine seriously and with respect the ‘Hockney thesis’ in the 2022 book of the exhibition edited by Martin Gayford, Martin Kemp and Jane Munro ‘Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction ’ London, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge and The Heong Gallery with Paul Holberton Publishing.

This book makes modest claims to be the beginning of a process in academic study and, more importantly, the way we interpret the world when we ‘look at’ it. I leave aside my quibble that the problem remains that we need not just only to interpret ‘the world in various ways’ but that ‘to change it’ as Marx insisted. The world changes however only when sufficient people see through the dynamics exerted by ideologies aimed at representing (often, in truth, misrepresenting) the underlying realities of its operations of inclusion and exclusion. And hence we ought to admire an attempt to redress the awful crass response of the history of art academic and institutional establishment, Martin Kemp and Luke Syson excepted, to address as the ‘Hockney thesis’.

In order to examine ‘the Hockney thesis’, Hockney’s Eye marshals together essays from different academic disciplines – in art, science (including the neuroscience of perception), technology and the study of the respective cross-cutting histories of art and science. It looks to develop seed lurking in the fertile soil of that thesis. Whether these attempts cohere into something substantive is another issue and it is important to remember that the editors forswear proposing any radical change or even conclusion on the thesis. They argue rather that they:

… are not taking sides in the noisy historical debate, but gathering together visual experiences addressed by the ‘Hockney thesis’, exploring how they enrich our own looking, just as they have nourished Hockney’s own vibrant practice. Visitors and readers can reach their own conclusions.[2]

Nothing could be less ambitious than this statement. The editors are neither attempting to ‘interpret’ the world nor show how such interpretation occurs. They are rather standing at a distance from the world (an ‘objective’ distance they might argue) and seeking enrichment of each our individual understandings of one artist’s individual practice: the language of ‘enrichment’, ‘nourishment’ and ‘vibrancy’ forswears any notion that the world differs from what the authorities of the status quo tell us it is. Rather the goal is something aesthetic that is considered parallel to the way the world operates, rather than something urgent that really matters for us to understand and act upon. Percipience and intelligence need to guide actions as well as words in the end if things are to change. This said, we can examine what I feel the book does within those limitations.

Before doing so, it is worth examining the self-definition of the book’s scope and contrasting it to what I see as the radical manner in which Hockney attacked the institutional status-quo. That attack may have been primarily on the ‘art world’ as he termed it but, by implication and directly, it attacked ideologies too, such as that which implies that truth statements can be delivered ONLY from one ‘correct’, authoritative and ‘fixed’ standpoint (‘ex cathedra’ as it were). Hockney’s take on art assumes interaction and contest between multiple viewpoints on art. One reason for this is that he considers visual art to be a cultural phenomenon that varies between and across cultures, temporally and geographically. In a record of various conversations with Hockney collected and edited by Martin Gayford, Hockney critiques one of the most authoritative of art historical textbooks, Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art (though Gombrich was a scholar he otherwise admires and who had supported the artist).

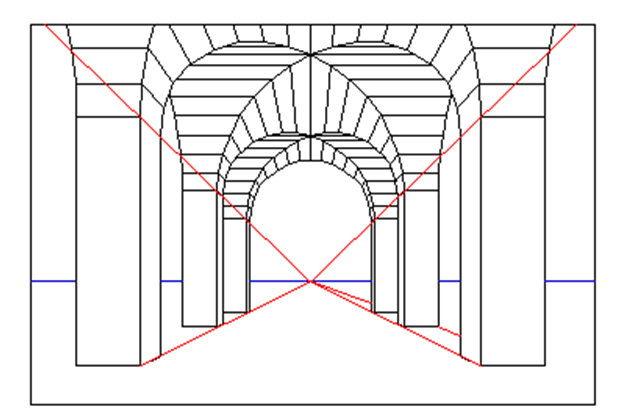

It’s clear that Hockney admires The Story of Art (he says he read it many times) but it was a prime authority for an assumption he seriously questioned and began to dislike. This is its assumption that the parameters of the solution of the problem how art depicts ‘reality’ had, once and for all, been set in art’s progress through history; in the art of Renaissance Europe. Hockney queries I’d argue whether ‘reality’ can be captured at all let alone once and for all; for ‘how we look at the world’ is continually problematic for a world in change. Hockney believes such questions are solved only within the limits set by the situations defined by particular spaces in particular times in cultural history: ‘it’s precisely how we look at the world that’s the problem’. The corollary of this is that the definition of an fixed viewpoint as the privileged point of view of what art shows to us whether as represented by the optical device of the camera or the abstracted representations of perspective in theoretical geometry is itself nought but a temporary solution to the issue. Thus, he argues, the practices of architect, Brunelleschi and books on perspective starting with the Alberti onwards, have corrupted (his word) ‘how most people see the world’ when translated to two dimensional art, a way he once ‘participated in’ himself.

From the 1970s onwards Hockney claims he was ‘thinking about what is wrong with’ this construction of how and what we see when we think we are seeing ‘reality’ as represented by the graphic above.[3] In another conversation he says the application in an inappropriate way of the laws of optics is of major significance in Occidental thought. It prompted in him an investigation into the multiple and moving foci of Oriental ways of seeing: saying ‘perhaps the big mistakes of the West were the introductions of the external vanishing point and the internal combustion engine’. The mistake with the former, he elaborates within the conversation, was that it created a false position (I would say an ideologically defined one) from which to view two-dimensional art; one which makes the viewer appear as external to the work of the cultural object, rather than integral to its making and meaning:

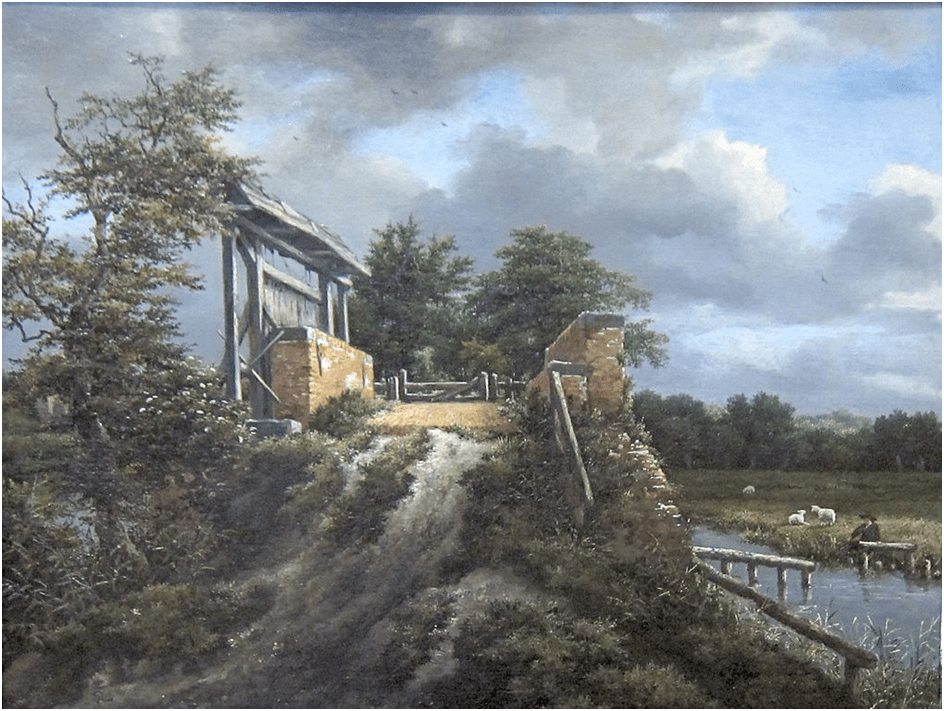

DH: It pushes you away. When I went to the Jacob van Ruisdael exhibition at the Royal Academy some years ago, I thought, “My God, you’re not in the landscape at all, It’s all over there.”

MG: You mean the viewer is automatically outside a picture constructed with single-point perspective? It’s made from a fixed point, and so similarly you, the spectator, are fixed?

GH: Very, very fixed.

MG: So there’s no such thing as ‘correct’ perspective.

DH: No, there isn’t. Of course there isn’t.[4]

In a letter to Richard Morphet (which the letter-writer dubbed a ‘sermonette’) Hockney characterised the effect of the kind of art history and ‘the art world now’ that valorised the principles of single-point perspective as the only portal to ‘reality’ as a kind of ‘intellectual corruption’ that had ‘spread everywhere’. The effects of that ‘corruption’ were facets are seen in the obsession of European Art ‘with its cameras, holes, windows and the illusion of depth that destroying lateral looking of the surface causes time to freeze’. I take this tight statemen to refer to two problems:

- That the part of the world we look at (through art’s ‘window’) is perceived as a whole and seen as a whole in one finite moment (however prolonged in reality), and;

- That our eye is immobile and fixed like the concept of a single viewpoint. It does not progress during a passage of time) laterally across the picture and thus reduces any chance of the picture being seen as dynamic or as including a narrative.

This is an effect cubism set itself to challenge Hockney argues (in this he is in agreement with Gombrich who saw the Hockney who joined up multiple photographs into one frame as a cubist). That challenge however was suppressed by the vast influence of the photograph’s claim to represent the equivalent of visual reality; nature dominated by an external viewpoint that immobilises it.

…; we believe we almost see that way, but it is really taking away the effect of memory on vision. It fires shapes and we believe they are fixed when we see them yet they can only be fixed, if time is fixed.[5]

And neither time nor history, nor our perspective on the ‘reality’ they unfold, is in truth fixed. Looked at from this perspective Hockney’s project in changing the way art is made, viewed , used, and talked about is I believe truly radical and has tentacles in the construction of political reality, And we will search in vain to see this reflected in a significant way by essays that test the ’Hockney thesis’ in Hockney’s Eye. We should first note the term used to translate Hockney’s project over many years into an intellectual proposition: a ‘thesis’ which can be stated in a way that reduces it to its supposed essence. This is the manner of science. It allows evidence for and against that thesis (and sometimes its antithesis) to be marshalled). The thesis is stated thus:

… that optical devices were used comprehensively by artists from the Renaissance onwards … . He is in effect saying that we (and art historians in particular) have missed the procedure that lay behind half a millennium of naturalism in art. In this scheme photography was not so much a new invention in the 1830s as a natural continuation of earlier instrumental imitation.[6]

Put like that the ‘Hockney thesis’ remains radical only for those who feel they are under critical attack for having ‘missed the point’ of that discipline (‘the history of art’) of which they profess to be expert (at least in as far as it relates to the bigger picture represented by the meaning of art having a history). These people are academics – especially academic art historians – whose limitations have been hinted at for some time by one of their own and one of the editors of this book, Martin Kemp. Kemp was always rather a rogue member of the club of academic art history if he is correct in the way he represents himself in a book I have blogged about in the past, Living With Leonardo – use this link to read the blog. In a blog on his latest book – on how the poetry of Dante is pictured in visual art – I describe his self-image:

… as being in large part being brought up a scientist but having gone on a different career trajectory, almost by accident. He tells you about this in the Living With Leonardo essays. It explains why he uses terms from mathematics, physics and statistics and devotes quite a bit of this book to optics in ways that never feel to be as central or necessary as the author wants them to be. It is also there in choosing to characterise Grunewald as looking like an ‘outlier’ (a term from graphic correlational analysis) when Kemp chooses to discuss him in the company of Fra Angelico, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, Bellini, Signorelli and Titian.[7]

Hockney underlined his own radical stance against the institution of art history by working (with Martin Gayford as his ally and who, in the text, acts as a facilitating interviewer in order to prompt Hockney’s ideas) on something that can be seen to displace the assumptions of Ernst Gombrich’s History of Art. He called his book A History of Pictures. This title promotes a democratic and anti-elitist stance on deciding what is worth looking at in the world and why. Its overall tendency is to ally itself with passing time and the acceptance of downward devolutions of social power in that change:

People like pictures. They have powerful effects on the way we see the world around us. Most people have always preferred looking at pictures to reading, perhaps they always will. I think that humans like images even more than text. I like looking at the world and I’ve always been interested in how we see and what we see. / … / … the difficulties of depicting the world in two dimensions are permanent. Meaning, you never solve them.[8]

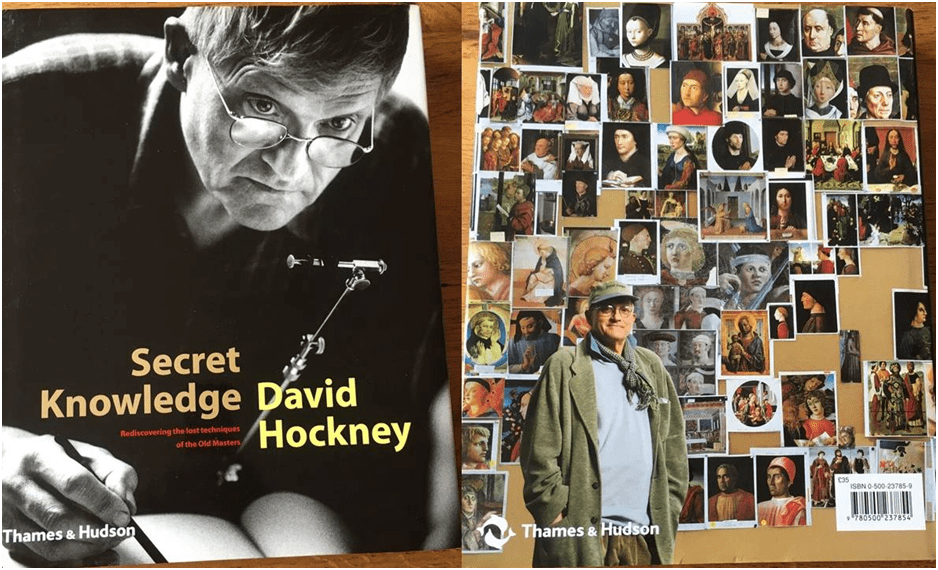

But Hockney’s Eye is, despite appearances, not another in the series of Hockney’s books that in the end assert the import of representation to the ideological issue of how reality is perceived. If anything, it returns to Hockney’s views that caused such ripples on the surface of art history in his first sally (in 2001 and expanded in 2006) against it. The editors themselves say that their agenda is shaped by Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Techniques of the Old Masters.[9] But even in this book the deeper agenda is not artistic praxis per se but a direct and urgent social message; in for instance characterising the Renaissance Master thus:

They were producing the only images around. The Master was part of the powerful social élite. Images spoke and images had power. They still do.[10]

Yet the analysis of the power of images in the context of the social structures and control systems of the status quo doesn’t quite (with one exception – in Martin Kemp) ever get raised in Hockney’s Eye I think. As a result the collection seems to fuse very different academic disciplinary approaches but it does so whilst maintaining their bounded separation. Thus nothing in the book is ever really radical, especially from the applications of the history of science. Another reason for this is that the case as a whole of the book does not take on, except in two prevaricating pages by Kemp, the important issue of what constitutes the evidence for a truth statement, something Hockney has always faced full on.

Some evidence, Hockney makes clear in Secret Knowledge, is deliberately kept ‘secret’ in the interests of not making the strategies of the powerful for maintaining their power self-evident. The processes by which their right to power are established are instead mystified in the name of, say, ‘natural’ genius or the myth that the naturally talented always rise naturally to the top, like cream. In truth it is the manipulative persons that always rise to the top of society if they are not already there by virtue of their birth. And this is particularly true of academic institutions and disciplines. Hockney makes the bold assertion for instance, supported by Martin Gayford in 2007, that internal evidence of the use of a camera obscura is readable in Caravaggio’s naturalistic scene settings of groups of figures.[11] Assertions like this set voices screaming from within the art history establishment that the Hockney was merely jealous of the geniuses of the past. Yet we find ‘breaks in visual continuity’ productive of ‘anatomical and spatial oddities’ caused by the movement of the fixed lens to capture details of a scene that then have to be ‘stitched together’.[12] It is not only that Hockney, his assistants and Gayford found such evidence analytically but that these predicted discontinuities could be reproduced by replicating the hypothesised method with actors even now – and Hockney and his assistants did this too.

The academic institutions, and their grandee representatives, were furious for being thus accused, as Gayford, Kemp and Munro say. Self-proclaimed ‘experts’ were neither ready to ‘entertain the idea’ that that the point regarding the dynamics of the social history of picture-making had been missed nor that ‘they’, in particular ‘might have done so’. Susan Sontag went as far in an academic conference as saying that the thesis was born not out of research but out the fact that, unlike the Old Masters, Hockney couldn’t himself ‘draw like that’ and hated the thought of anyone else being able to.[13]

I see Hockney’s Eye as an intervention at the level of the academic institutions therefore. It is a text that makes attempts at drawing together disciplines but not shattering the self-image of the disciplines with anything that might defy their self-generated rationales. Thus it sticks to areas of consensus and really only investigates artists where the links to the use of optical devices in image-making is fully agreed, apart from in the case of Ingres perhaps. I will consider the masterly essay on Ingres by Jane Munro later. In large, I would say, the argument of Hockney’s Eye has shifted the focus, even for Martin Gayford that old ally of the thesis, from ideology to analysis of the clever ways in which Hockney exposes the devices by which space is created in order to demystify processes generated over a millennium and more. This is how Gayford’s brilliant analysis of Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1966) works, for instance.

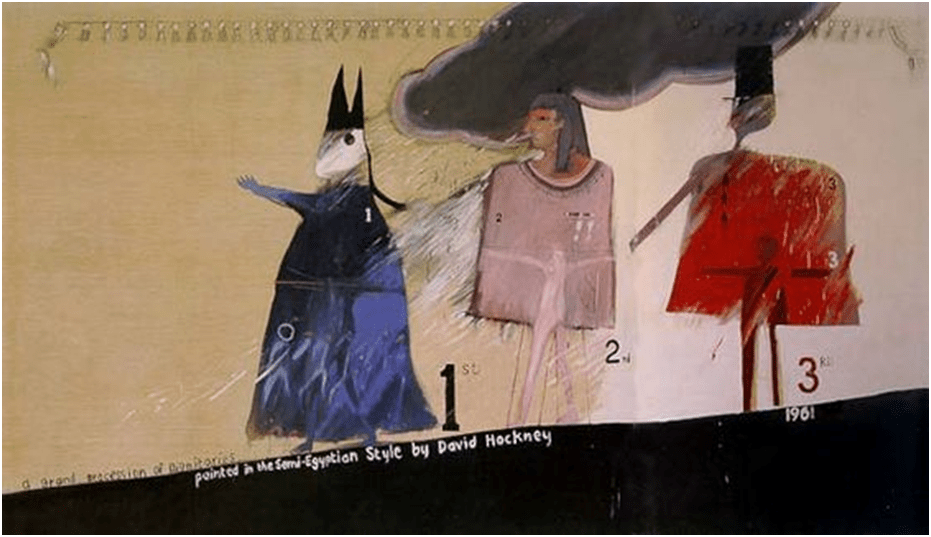

In this remarkable analysis, Gayford points to the manner in which it references visual devices and tropes utilised by other painters, like Cezanne and Bacon to solve common problems of perception but not to emphasise effects of power. And perhaps he is correct that in 1966 Hockney’s ideas were less formed about the problems of the photograph as a key formative influence in describing reality. However, Hockney’s ideas about the power of the image in public and private political systems were well worked out, as I would argue his 1961 A Grand Procession of the Dignitaries in a Semi-Egyptian Style shows. Gayford however here discusses this painting only in terms of stylistic characteristics.

When Gayford interviewed him for their 2011 book, Hockney deliberately links ‘Egyptian style’ to the moulded realities in the mind of contemporaries of images of power. For me this explains why images of church and the military state in the painting parade their intention to control the image of the masculine whilst playing with its boundaries themselves in authorised frocks (a view shared by many in the queer community in the 1960s). Locked inside the enormous volume of these overdressed individuals’ idea of their own ‘dignity’ is the poor bare forked animal (almost a suffering Christ) faintly drawn and icons of the masses walking in the opposite direction to the oppressive clouds of the ‘dignitaries’.

Isn’t the eye part of the mind? If you look at Egyptian pictures the Pharaoh is three times bigger than anybody else. The archaeologist measures the lengthy of the Pharaoh’s mummy and concludes he wasn’t any larger than the average citizen. But actually he was bigger – in the minds of the Egyptians.[14]

My feeling is that even Gayford and Kemp take a step back to academia in order to appease it, and stay relatively comfortably within it, in this book. In terms of the essays on science and the history of science too, although interesting facts and insights are available, none advance the Hockney thesis and merely illustrate it. Even the essay by a neuroscientist, an arena where an understanding of power is urgent, Anya Hurlbert instead looks at how predicates of her scientific specialism, the study of colour vision, illustrate:

… complicated interactions between illumination, shape, and surface properties, intensely explored in the study of human vision and implemented in machine systems, yet grasped in their entirety by Hockney, and transformed into art’. [15]

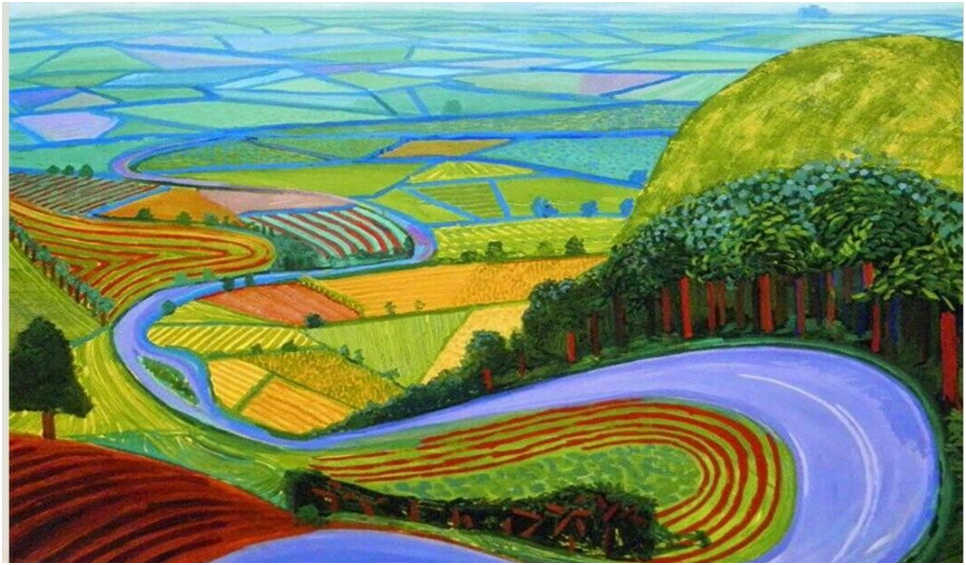

But there you have it. In this sentence we are interested only in the relationship of the mind of the individual artist and art, not in the social depth analysis of culture and the power of images. The academy represented by the editors and commissioners of Hockney’s Eye has returned to backing up a renewed institutionalised art history, which has been allowed to specialise in its subject, receiving contributions from other disciplines, rather than dare a co-shaping of a cross-disciplinary agenda that addresses the issue of social power, stasis and change. There is room for such approaches and the quality and range of them here is highly impressive and highlights the achievements in innovative aesthetic form and dynamism in Hockney’s own art. One essay explicates, for instance, the necessary distortions, from the point of view of a fixed point perspective, in two dimensional paintings that attempt, as Hockney does, to convey the temporal duration of our experience of the three dimensional world. Its urgent address of this problem in the aesthetic realm is praiseworthy. We see its relative force in fine and suggestive, if not totally transparent, sentences such as these from that essay by Zoe Kourtzi, Andrew Welchman and Martin Kemp that addresses paintings such as Garrowby Hill (1998):

The relationship between sensory events and physical events becomes a matter of ‘feeling’ the forms, spaces and colours under the scrutiny of our mobile eyes and subject to our mobility as a spectator. … [Hockney] exploits vertiginous instabilities in his images of the Grand Canyon and Garrowby Hill.[16]

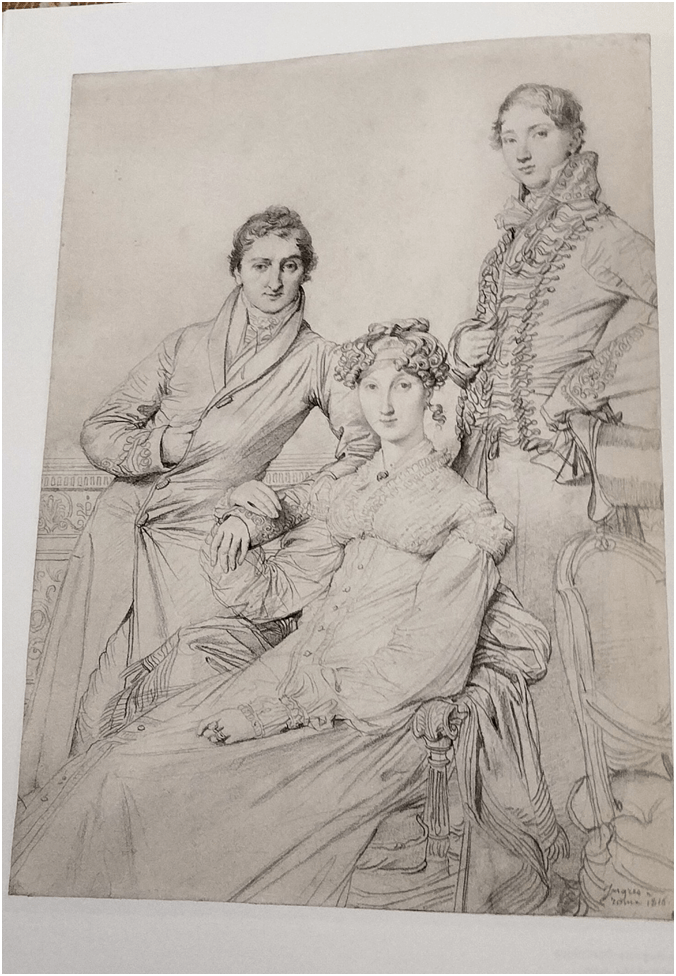

Otherwise some essays are slightly dull versions of similar points adding to ‘scientific’ credence by the authorities involved: the most illuminating (because it crosses disciplinary boundaries) is on Hobbema, the dullest on Cornelius Varley’s invention of the optical device he called the Patent Graphic Telescope. But all are more than worthy pieces of research. There is a rather stunning essay, which not only crosses but transgresses boundaries creatively and it makes much of the rest of the book pale in significance to it, which is an essay on what Hockney learned by modelling his practice on his theories about the possible use of optical devices by Ingres. I want to spend a little time with that beautiful essay by Jane Munro.[17]

This matters to me because it investigates the implications raised by Hockney about how oppressive political power is either replicated or challenged by art, and does so in ways that are true to what Ingres may have used optical devices for and its political effect (if Hockney is correct). Hence it is also about how the modern artist used that ‘knowledge’ to find skills as an artist that would challenge that political effect in ways that are critical of oppression. Hockney deduced that Ingres’ style as a portraitist was based on the use of a camera lucida, despite the lack of documentary evidence for that.[18] (Ingres’s portraits were of the privileged classes of Europe who beat a path to his studio door). Munro’s extended account of the Hockney argument is comprehensively researched, beautifully narrated and convincingly applied. It turns on the usual justification for the use of a camera lucida in collecting details of the proportions of one’s model as a figure in the painting. It ‘allowed the artist to achieve a pleasingly “uniform scale”’.[19] Uniformity in the proportion of figures in portraits was of great value to sitters in the early nineteenth-century, who would pay higher prices as a result based on the relative proximity it allowed for having a full-length figure. Whilst Hockney does not suggest that the accuracy of Ingres uniformity of figure could not have been achieved without an optical device, he and Munro seem convinced that it would have been used, given the speed of initial sittings with the socially prestigious models, not to achieve his artistry but to ‘position key facial features’ (and other features) before completing artfully using direct observations.

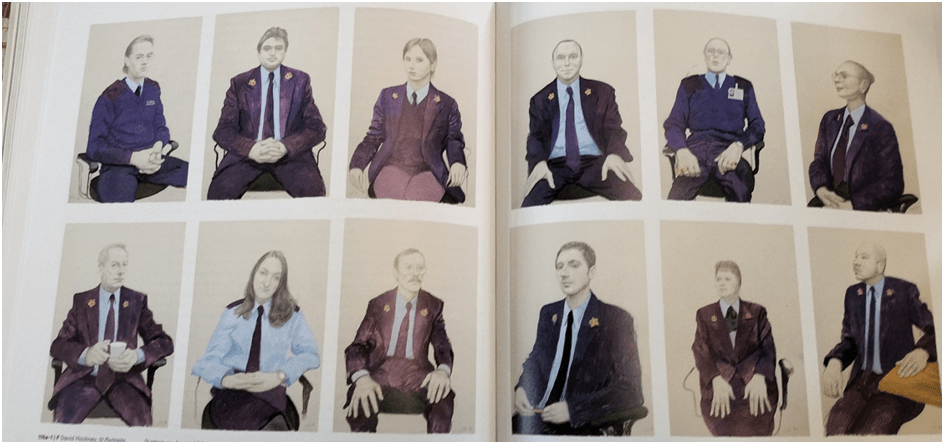

Hockney responded to Ingres’ portraits in an exhibition at the National Gallery in September 2000 with twelve portraits of uniformed gallery staff. For for these low-paid workers uniforms represent a symbol of their wage-slavery to the art institutions that did not otherwise cater for people of their class and status. Munro says the emphasis on uniforms however was only by and large a ‘witty and insightful homage to Ingres’.[20] But surely it is more. On the one hand, Ingres valorised the individuality with which he was able to pay homage to wealthy sitters who earned him his considerable income by the use of uniformity gained (Hockney thinks) from optical devices. Hockney, on the other hand, valorise, (as Munro illustrates well) the diversity of the gallery staff despite the attempt of the uniform (the same clothing that institutionalised them) and the ‘uniform’ poses Hockney actually imposed on them. Whilst Ingres’ sitters may rejoice vainly in the uniformity of their images with a received idea of their social worth, Hockney’s sitters establish their own unique characteristics as a function of their reduction otherwise to ‘uniformity’ (unisex regulation blazers … and institutional insignia’). Art suddenly is not guarded by them for the sake of entitled classes but is owned by them and their contributions to the portrait-making; ‘one holds a cup of tea, another twirls a pencil’.

As I reflect back on writing this I register some concern that I find fault with some essays merely for not being interesting to me, for no essay in this volume is a bad essay. I suppose I forgive myself for I write from an unashamedly subjective position after having enough of institutional politesse and ready now to say what really matters to me, which is, in brief, that learning should be aimed at changing a world too full of inequalities and too disregarding of actual diversities. This situation is getting worse. The problem of the supposed ability of the universities to sit outside the social chaos outside them has long been exploded. Many are going full tilt for the exploiting the market for their goods before it shrinks in the knowledge that as repositories of values, knowledge and skills, they have betrayed the many in society for too long by claims to a democracy of knowledge they have not promoted.

Hockney’s Eye’s commissioners claim this book is evidence for a new alignment of the interdisciplinary in Cambridge and perhaps more widely. One of the editors, the least likely in my view (Martin Kemp), actually does pick up on Hockney’s project as political although he says Hockney’s attack is directed at too limited a target – not just the artistic users of optical devices but the entire project of naturalism is to blame for to-down controls he says in correction of Hockney.[21] (Personally I don’t think Hockney ever says the use of the devices is the object of his blame, rather the ideology they represent.) Moreover, it is still the role of the academy in Kemp’s eyes, it seems, to hold back the horses of the passion of artists with a ‘yes, but …’.[22] But Kemp’s essay is a good humoured one and a testament to the probity of an academic that, unlike many others, accepts challenge from wherever it spring and which he himself often explains by his own maverick social and academic background. If you are interested in the continuation of education in the history of art, this book is a must of course. There is also much in it to appeal to anyone wanting to grasp the significance of Hockney’s praxis. Read it. Why not?

All the best

Steve

[1] Alan Bookbinder (Master of Downing College) & Luke Syson (Director of The Fitzwilliam Museum) (2022: 7) ‘Foreword’’ in Martin Gayford, Martin Kemp and Jane Munro (eds.) Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction London, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge and The Heong Gallery with Paul Holberton Publishing, 7.

[2] Martin Gayford, Martin Kemp and Jane Munro (2022: 12) ‘Introduction: the “Hockney thesis’’’ in Martin Gayford, Martin Kemp and Jane Munro (eds.) Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction London, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge and The Heong Gallery with Paul Holberton Publishing, 11-17.

[3] Hockney in Martin Gayford (2007:52 & 50 respectively) A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney London, Thames & Hudson.

[4] Hockney (DH) & Gayford (MG) in ibid: 58, 61.

[5] David Hockney (2021: 141) ‘Moving Focus’ in Helen Little’s (ed.) ‘David Hockney: Moving Focus: Works from the Tate Collection’ London, Tate Publishing, 140f.

[6] Martin Gayford et.al: 12

[7] Blog available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/05/20/i-tend-not-to-like-conclusions-and-have-a-sense-that-it-is-best-if-the-end-is-left-rather-open-i-am-not-sure-this-is-quite-the-book-i-set-out-to-write-the-lim/

[8] David Hockney & Martin Gayford (2014: 19) A History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer Screen London, Thames & Hudson.

[9] Martin Gayford et.al: 11

[10] David Hockney (2001: 15) Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Techniques of the Old Masters London, Thames & Hudson

[11] Martin Gayford (2007: 126ff.)

[12] Ibid: 130f.

[13] See Christopher Simon Sykes (2014: 346) Hockney: The Biography, Volume 2 1975-2012London, Century Random House

[14] Martin Gayford 2007 op. cit: 53

[15] Anya Hurlbert (2022: 155) ‘Colour in the mind of Hockney’’ in Martin Gayford et.al. op.cit: 145 – 155.

[16] Zoe Kourtzi, Andrew Welchman and Martin Kemp (2022: 139) ‘Hockney through the mind’s eye’ in Martin Gayford et.al. op.cit.: 135 – 142.

[17] Jane Munro (2022) ‘Ingres and Hockney: Art, science and uniformity’ in Martin Gayford et.al. op.cit.: 113 – 131.

[18] Ibid: 122

[19] Ibid: 124

[20] Ibid: 127

[21] Martin Kemp (2022: 48) ‘Seeing through perspective’ in Martin Gayford et.al. op.cit.: 41 –61.

[22] Ibid: 56

Other blogs I have done on Hockney are available from links here:

On the book Moving Focus:

On the art in Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy :

On a poem about early Hockney and other things by Andrew McMillan from an exhibition on: Alan Davie & David Hockney: Early

One thought on “In a Foreword to a book relating to an exhibition based on David Hockney’s stimulus to the academic world to revise its boundaries, in the history of art at least, Alan Bookbinder and Luke Syson say that the ‘project demonstrates that the phenomena of seeing and experiencing are germane to both science and art’. They go on to claim it represents ‘easing’ between these academic disciplinary borders that will, by ‘cross-pollination of ideas and innovation help us all look differently at the world we inhabit’. This blog reflects on a much needed attempt to examine seriously and with respect the ‘Hockney thesis’ in the 2022 book of the exhibition edited by Martin Gayford, Martin Kemp and Jane Munro ‘Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction’”