Interviewed in 1969 for The Observer, Rhys sought to ‘distance herself from the women whom she wrote in her novels. While agreeing that they often underwent similar experiences to their author, and bore an acknowledged resemblance to aspects of her personality, Rhys pointed to a crucial difference. They were victims. She herself was not’.[1] This blog reflects on the presentation of women as victims and why that trope was still necessary one for a woman to explore, who regarded herself not as a victim but as a survivor. This blog also reflects on the high quality of a biography by Miranda Seymour (2022) ‘I Used To Live Here Once: The Haunted Life of Jean Rhys’ London, William Collins Publishers.

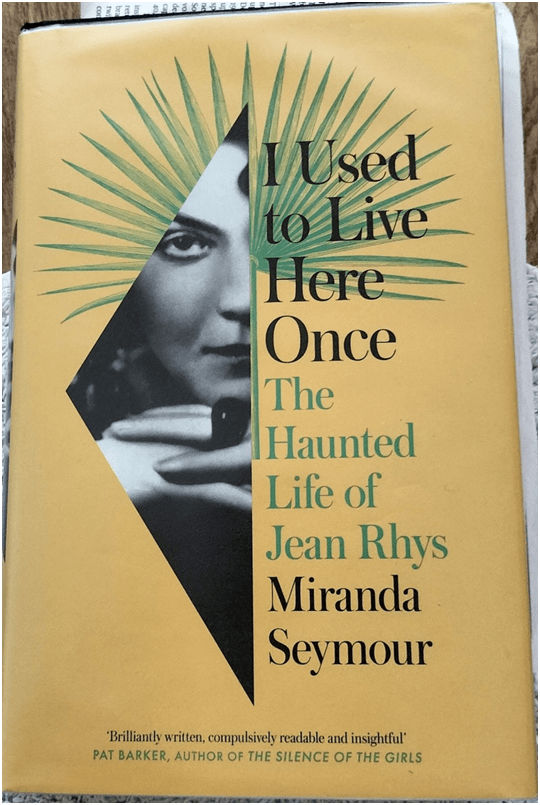

Reading newspaper reviews of this latest of the biographies of Jean Rhys reminds how contested is the field of biographical writing. Sometimes there seems an unforgiving double bind, to use Gregory Bateson’s phrase in the demands put upon that hapless creature who attempts to tell the story of someone’s life and somewhat to recreate what it felt like to live that life or observe it in the same historical moment. You can go for underlying explanation of the person’s behaviour, thought and emotion, through ‘detective work’, insight and research into the behaviour of your ‘subject’, as Carole Angiers in 1990 did, (according to Claudia Fitzherbert in The Literary Review). Otherwise you might, as Fitzherbert says Pizzichini did in 2009, use the novels as means to imaginatively ‘recapture’ moments from the life. Each approach might produce brilliant persuasive books but they still fall foul of promoting ideas that are frankly not as explanatory as they seem (that Rhys had a personality disorder, for instance, in Fitzherbert’s summary of Angier’s ‘underwhelming conclusion’) or make too many assumptions that fiction must arise from autobiography in some direct way, as Fitzherbert sees in Pizzichini.

Given these failings in early biographies, it seems unfair that Fitzherbert sees the very opposite of both tendencies (for over-explanation and easy assumptions based on acknowledged fictions) as ALSO a fault. Seymour is castigated, although not without nuance as the review proceeds, as being overly involved in telling the story in as objective a way as she can. Fitzherbert says, or implies, that this stops Rhys ‘speaking for herself’ and leads to more summary than sense-making as a result.[2] Yet the same reviewer admits to the truths that Seymour’s method uncovers – of the many difference between Rhys’ primary female characters and herself and the manner in which assumptions of the opposite have marred our readings of the novels as the pained cries of a victimised and passive creature. I think Fitzherbert might have been more generous to Seymour in all of these points. Moreover, I cannot find this myself in the book, which reads tremendously well, telling a story and drawing a character that rings as so true, so moving, and so resilient without actually denying the horrific injustices caused by male power throughout. And part of that is also about showing us a character many will find it difficult to like and who is at times as selfish and wilfully aggressive and disruptive, most often to other women from she was offered care, as it is possible to be.

Other reviewers see things much as I do here, stressing the empathy for Rhys even as the worst sides of her personality and behaviour are described or seen through the lens of those whom, as an older woman, she harassed and frankly, terrorised, such as Diana Melly (Melly offered Jean a free home and support for a while). John Walsh in The Sunday Times says that, because it is ‘a rollicking read’ and includes new research in Rhys’ birthplace, Dominica (visited by neither of the earlier biographers), it is ‘close to a masterpiece’.[3] In The Guardian Rachael Cooke says that, though Seymour’s Jean Rhys may be ‘shot through with madness’, when we consider the drama of her life that way of understanding her behaviour hardly stands out:

Half its cast are half crazy, and most of the rest are as creepy as hell. Liars and fraudsters, bigamists and bolters, grifters and gropers: they’re all here, though Seymour has a special line (because her subject attracted them) in the kind of literary stalker whose pulse races furtively at the sight of an old woman with a bad wig, a whisky habit and (just perhaps) a half-finished manuscript in a drawer.[4]

But what appeals to me in both of the last-mentioned reviews is a point entirely missed by Fitzherbert; that Seymour is as interested and illuminating about the older Jean Rhys as about the childhood or mid-adulthood of the same woman. Because the early and middle ages of women nearly always takes centre stage in biographies of historically significant individual women, their old age is often implicitly presented as a kind of embarrassment. Walsh says that, though expecting ‘the final pages to be all geriatric decline’, they were ‘full of incident’: a story as well-told and made an interesting read as any other part of the book. While less enamoured of Walsh’s ageist language, his point is similar to Cooke’s: ‘It’s the second half of the book, in which [Rhys] is old and ‘potty’ and half-cut, that is Seymour’s triumph’. Again exclusionary language is a problem here but not so in Seymour herself.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/may/16/i-used-to-live-here-once-by-miranda-seymour-review-the-troubled-life-of-jean-rhys

Sometimes people generally fail to register how deep set are the assumptions of ageism, especially in relation to women. But the responses of Walsh and Cooke are registering the real surprise of an ageist culture caught out in its assumptions. Fitzherbert’s silence about this tremendously innovative feature of a life is more in line with unconscious complicity with ageism. And we need to understand Rhys’ older age precisely because it illustrates how intersections in perceived identity complicate our take on the mechanisms of power in society. Strangely, even though Rhys’ final isolation strikes us as sad, her embrace of it is both gutsy and brave, cocking a snook at social expectations of not only female behaviour but the behaviour of older people, especially older women who continue to drink heavily.

This is all the more important in that Rhys herself makes a point of looking at the fears of women facing older age. A.L. Kennedy says of the two novels which preceded Good Morning, Midnight, they seem to use a continual metamorphosis of the same kind of character but that with each novel ‘the protagonist is slightly older and slightly reworked’.[5] In the latter, Sophia (who is known as Sasha) Jansen learns how she has become seen as ‘la vielle’ herself (the old woman): ‘ “…who is he talking about? Me? Impossible. Me – la vielle?”’[6] Yet in the same novel, Sasha feels common purpose against a woman her own age that seems ready to condemn her own mother largely for the sin of living to an old age that the daughter projects as a fearsome ridiculous-looking thing. They all three meet in a shop where the elder looks for ‘pretty things’ that she might ‘wear in my hair this evening’. The older lady is however ‘perfectly bald on top – a white bald skull with a fringe of grey hair.’

The daughter’s eyes meet mine in the mirror. Damned old hag, isn’t she funny? … I stare back at her coldly.

I will say that for the old lady that she doesn’t give a damn about all this. … A sturdy old lady with gay, bold eyes.[7]

This book was published in April 1969 and Rhys was 48, yet it is this minor character (appearing only in this brief episode very early in the book) that predicts Rhys’ own old age, as Seymour describes it at least, rather than anything feared by Sasha Jensen as she declines through her novel into passivity and victim status. Although Seymour does not cite the piece above, she might have done when she says: ‘it’s rash to read Good Morning, Midnight as an artless account of Rhys herself, or even as a vision of the woman she feared she might become’.[8] And Rachel Cooke vouches for the fact that Seymour does not do that, especially of the Rhys in her eighties:

Seymour does not make the mistake of portraying her as a victim (Rhys died in 1979, aged 88). However precarious her existence, as she appears in this biography Rhys always maintains an obscure dominion, if not over herself, then over other people. Her intransigence, capriciousness and abiding selfishness may not be pretty, but it’s these qualities that kept her going against all the odds.[9]

It is not just that the books are far from artless (they are the acme of writing as processed through the finest of artistic integrity) but that her main characters are always seen as too ready to embrace a self-willed victimhood, fuelled by the choice of alcohol and isolation as their only escape, except for, perhaps, a room to hide in: ‘Who says you cannot escape from your fate? I’ll escape from mine, into room number 219’.[10] There are ways of reading a novel, even one as apparently dark as Good Morning Midnight, other than detecting autobiographical projected gloom and alcoholism that suggest that Rhys survival was in part based on the ability to escape the monotone of sad despair with which some readers read her. It is with respect to this that Seymour opens up my response to Rhys, so that I even begin to like Good Morning, Midnight more, though it is my least favourite novel of this master of prose. I once felt it to contain much more in it of the most plangent of Rhys’ lines of supposed abandonment to yet another case of alienated anomie, or to her real detractors victimised longueurs, sometimes found to be the essence of all of her novels: a female colleague teaching her with me on a university course on The Novel back in the day called it the ‘Shall I kill myself today or have another whiskey!’ theme. Seymour restores it for me in insights like this which trace some of these passages of gloom to the intellectual and cultural climate of her contemporaries, such as the surrealists Robert Desnos, Man Ray and Céline (supplemented of course by George Moore’s Esther Waters. Seymour says that Good Morning, Midnight:

… reveals better than any other of Rhys’s novels the chasm that divided Jean’s chaotic life from the disciplined clarity of her writing. Behind Good Morning Midnight, even more skilfully concealed than in Voyage in the Dark, lay the wealth of a cultivated mind. …

A Beckett-like vein of black comedy and occasionally pure slapstick provides a steady counterpoint to the vortex of Jansen’s descent.[11]

Seymour’s thrilling re-reading and re-contextualisation of the relationships between the very different arts and sciences of writing, and surviving life, led me back to re-read novels I haven’t read since I taught them at Roehampton in the 1980s. I re-read three of them. I still found myself most resistant to Good Morning, Midnight but I don’t doubt Seymour’s correctness about its much richer cognitive affective range than I find. The novel clearly thinks through emotions thought to be simple, even simplistic, more than any writing I know and uses an aesthetic prose style that does not dress itself in its aestheticism or even style, for both factors hide under the work the prose is doing. I would like to illustrate that from my own perspective before moving back to Seymour’s brilliance as a biographer and critic. My points are based on rereading After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Voyage in the Dark, and Good Morning, Midnight.

What you notice in re-reading is the apparent artlessness in dialogue, description and soliloquy and the famed simplicity of the choice of keywords, the repetitions of which you almost don’t notice so varied is their range of contextual use and meaning: words about simple binaries (apparently) like hard and soft, warm and cold, light and dark, the clear and the distorted, leaving and staying, the enslaved and the free and, of course, death and life. Then there are also the constant but not overly insistent reference to real things that segue into metaphor and symbolism like animals, insanity, suicide, masks, the sun, money, books, artworks, walls, ‘touch’ and the condition of being a ‘lady’. It is almost impossible to say how brilliantly this is done but it is NOT (I am certain), as Carole Angier says it is, based on distrusting words and ‘trying not to use words at all’. That is not why I think Rhys said, cited by Angiers, that Voyage in the Dark was “almost entirely in words of one syllable”.[12]

Consider, for instance, the pieces taken from a passage in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie in which Julia in meets her sister Norah in a hotel after a long absence in which Norah has lived with and cared for their comatose mother.

She [Norah] had a sweet voice with a warm and tender quality. This was strange because her face was cold, as though warmth and tenderness were dead in her.

/…/

She had been accustomed for years to the idea that her mother was an invalid, paralysed, dead to all intents and purposes. Yet, when Norah said in that inexorable, matter-of-fact voice: ‘She doesn’t know anybody,’ a cold weight descended on her heart.[13]

Compare the deadpan play on words like warm and cold above, where minor changes of application and reference make the word rich in suggestion. Even though here the binary ‘warm and cold’ references the sensations of emotional effect coming from the way people deliver information to us; it spreads to the process by which one person intuits evaluations of both the nature of the personal interaction as well as of the internal characteristics of a person they are interacting with. These perspectival shifts in the way the words are applied to different subjects is what makes the words rich even in this restricted example. But those evaluations of interaction and simultaneously of the essence (even of groups of people and/or abstracted notions of colour) is even more ethically ambivalent in Voyage in the Dark wherein Anna, ever feeling cold in England but remembering the warmth of the sun in Dominica, also says of her memories of her black nanny, Francine: ‘Being black is warm and gay, being white is cold and sad’.[14]

“… I wanted to see you again,” I said.

Then he started talking about me being a virgin and it went – the feeling of being on fire – and I was cold.

“Why did you start about that?” I said. “What’s it matter?” …

/…/

… “You’re right,” he said.

But I felt cold, as if someone had thrown cold water over me. …

/…/

… But he laughed and squeezed my hand and said, “What’s the matter? Come on, be brave, “ and I didn’t say anything, but I felt cold and as if I were dreaming.

When I got into bed there was warmth coming from him and I got close to him. …[15]

The range of reference of the warm / cold binary is even greater and shifts so much from the potential of registering merely the sensation of physical heat and temperature (of things (like water), places and of bodies and their relative proximity) that we have to continually recalibrate our confusion and/or allow an overlap between these meanings – one often implicit anyway in their etymology but not always. For we cannot know why exactly white is cold and black is warm to Anna but the multiple ambiguities (of cognitive association or the sense of bodies or of the places where those colours are encountered) all act as in a rich poem. Sometimes the effect is like the way feeling and perception enact facts as in the room in which Julia and Norah’s dead mother lies, where a fire need no longer burn. But the lack of a fire is not why it is dark and cold and very empty’ is it? Or not that alone. The senses capture the underlying truth of things, like the smell when the body of a loved one begins to decay, that in itself strikes us as cold, even if the word is not used of this sensation in particular but of others: The room ‘smelt, faintly, of roses, and another smell, musty and rotten’.[16] The same ambivalence and multiple responses apply too to the way women experience male bodies as well as male attitudes and we will never know in short what the exact nature of the ‘warmth’ coming from Mr Jeffries is as he goes to bed with Anna in the quotation from Voyage in the Dark above, but it hasn’t the same resonance as the warm body of Francine in Anna’s memory of her childhood. This is not the language though of someone who does not trust words as Angier says. It is the language of a master of the complex effects even simple words can have in their repetition – for repetition may in fact betoken constant change and metamorphosis of feeling, sensation and even meaning.

And we know Rhys knew this because she shows us her characters reading and making the same play on words, asking us how we read letters, often quoted at full length, addressed to others than ourselves. Do we find them mean or rich, warm or cold? How does what we feel compare with the character’s response – say of ‘indifference’ (a ‘feeling’ so often invoked we realise that it can be a very dynamic rather a dulled response). It is even done with Julia in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie reading Joseph Conrad’s Almayer’s Folly, where the meaning of words like ‘slave’ in relation to the feelings of bondage, freedom and rebellion for women are particularly wrested out of Conrad’s control as the passage she reads chimes with her iteration of her saying to herself, ‘It isn’t fair, it isn’t fair’: “The slave had no hope, and knew of no change. She knew … of no other life”.[17]

I have no hope here of conveying how rich Rhys is to read – there are better passages than those I have chosen (often quite randomly) from these novels alone. However, I have written at such exhaustive (and no doubt exhausting) length because I want to defend Seymour from statements like those of critic Claudia Fitzherbert’s that Seymour writes of the novels ‘as though novels were traps for future biographers’.[18] For that is not at all the case. Seymour says correctly, and with brilliant illustrative quotations, of After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (which Rhys considered, it seems, ‘her best novel’): ‘Rhys’s prose approaches poetry in its evocative use of images – … – to conjure up Julia’s thoughts’.[19] Though it is actually much more than just ‘thought’ (as I hope I show above) that gets conjured.

Speaking of conjuring, the novels (despite their realism) exploit many supernatural figures: ghosts, doubles, vampires and the rituals of obeah. Seeing these as merely pointers to the theme of mental illness, or at the least a word to which ‘reason’ cannot be applied, which is how Carole Angier reads Voyage in the Dark, as if meaning could only come through images not ordered words and organised narrative (‘Words and rules are meaningless’ to Anna, she says).[20] Yet it also seems to me that it is far too easy to suggest that women’s writing partakes more of the unconsciously imagined than the struggle to see how the world works using sensation, feeling and thought through the vehicle of language as your tools. For instance if we look at the use of the obeah-derived supernatural references (here specifically vampiric witches known as soucriants) in Voyage in the Dark, these are not used as mere means of picturing emotional projections and identifications but as ways of interpreting the world of men who merely abuse women sexually and turn them into what they are themselves – unreasoning monsters in someone else’s fantasy. For this appears just after Carl Redman flees her bed, afraid of the sexual response he has imposed as a response From Anna:

Obeah zombis soucriants – lying in the dark frightened of the dark frightened of soucriants that fly in through the window and suck your blood – they fan you to sleep with their wings and then they suck your blood – you know them in the daytime – they look like people but their eyes are red and staring and they’re soucriants at night – looking in the glass and thinking sometimes my eyes look like a soucriant’s eyes.[21]

Women subject to male sexual use of the unwanted fertility of their bodies know that ‘as soon as a thing has happened it isn’t fantastic any longer, it’s inevitable’. Thus women learn to take the consequences of male libidinal and sexual irresponsibility and accept that it is they who must hold the baby and bear the social and economic consequences of its birth. There is a working literary intelligence behind this of a high order, abandoning commas, for instance, in the prose here to emphasise the traumatised disorganisation of the senses in Anna at this moment.

Seymour is somewhat blamed also by Fitzherbert for being ‘content that much in Rhys’s life “remains unclear”’.[22] Others just accept that what Seymour means is that Rhys’ literary intelligence was not that of the educated Western male and Western male institutions and open to influences those traditions would disdain. Thus the lively Rachel Cooke of The Guardian:

You cannot work her out: the violent ingratitude, the fondness for Ronnie Corbett, the fact that she has read George Moore’s dreadful 1894 novel Esther Waters 60 times.[23]

For I don’t understand either how such literary intelligence as Rhys’ could value so much the autograph of Ronnie Corbett. Yet she did as Seymour tells us. [24] Her ‘violent ingratitude’ I can understand better, for that hitting out at people who reflect images of what one is not but that you feel you ought to be, or who appear to be enforcing some painful awareness of one’s inadequacy in some realms, is accurate of the psychological responses often evoked in people who have abused alcohol and will again. ‘Violent ingratitude’ is also examined in the novels, in terms of responses made by her main female characters while drunk, or getting drunk, or sobering up slowly, or even feeling vulnerable about one’s dependency.

The examination of conflict between women is brilliant in her novels and emphasises why this lady often felt she was not a ‘lady’, as do most of her primary female characters. That examination is of the utmost importance I’d suggest to what these novels have to tell us about the oppression of women and how it might be mitigated, at the very least, or preferably, eradicated. People talk about Rhys often as apolitical or as only interested in the personal in politics but her passion for the ‘underdog’, even the claim (usually ironic) that she was a socialist keeps emerging in Seymour’s brilliant multi-faceted account. How do we explain why Sasha Jensen in Good Morning, Midnight is so cleanly ironic about the way young men ‘sheer off politics. It’s rather strange – the way they sheer off politics’.[25] Seymour shows that her empathies with those in poverty led to her being named by her family ‘Socialist Gwen’ in her youth in Dominica.[26]

When I was younger people saw Rhys as illustrating chiefly the oppression of women by men and not just patriarchal values. I see this lack of nuance much less these days, for it is not the victim that is outlined in her major characters, despite their downfall. Structural male power is implied throughout of course, but it only indirectly leads to the descent of Sasha, Julia and Anna into their particular infernos, for each is clearly marked as contributing and increasing the pace and depth of that descent, whatever the insensitivity and sometimes plain vileness of some, if not all, of her men. Moreover her analysis, if that is what it is, does not stop only at the way the sexualisation of female bodies becomes a means of the marginalisation of the person and the failure of a potentially socially successful set of talents.

Yes, Anna is a ‘tart’ (to use the word used in the novel) as well as a chorus girl and Sasha and Julia both live entirely off the money they persuade men to give them sometimes in exchange indirectly for sex or attention. But Good Morning, Midnight also tells the story of a male tart, if under the more acceptable name of a gigolo, and evokes the descent of male queer men in parallel with that of sex workers, such as momentarily Wilde, Verlaine and Rimbaud (although you can miss their appearances fairly easily). Largely men hide behind the ‘high, smooth unclimbable wall’ of their inability, or lack of desire, to communicate.[27]

The other reason we fail to see even her main characters as primarily victims is that they are largely escapist and that escape is via alcohol. This trait Rhys share with them but you cannot write novels of the quality and innovative nature as those she writes if one is merely escapist and / or intoxicated all of the time, as Anna, Julia and Sasha most often are. And drink makes the latter three passive, and accepting – perhaps even welcoming – of their disintegration. In contrast, Seymour points that the age of Prohibition almost made heavy drinking acceptable for people of her class and that nobody:

thought any the worse of Rhys for getting drunk, until drink unleashed her demons. “I’m not one to whine like some women do,” she told a writing friend in later life: “I attack”.[28]

And, in a way, I think Rhys is so great in part because she set out to understand how escapism from oppression and attack on anyone who might substitute for the oppressor, and sometimes was the oppressor, that anything that pretended to offer ‘security’ (positively or negatively) always seemed like a prison not a haven of safety. For this is a theme of her novels and her life. This moment for instance in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, is sometimes thought to mirror the moment Rhys was dropped from the protection and literary promotion, at the cost of sex, by Ford Madox Ford, but is in fact an analysis of what it means to ‘leave’ or be ‘left by’ men in the guise of social power. Given a cheque by Mr Mackenzie for 1500 francs, Julia felt that she:

… had always expected that one day they would do something like this. Yet, now it had happened, she felt bewildered, as a prisoner might feel who had resigned herself to solitary confinement for an indefinite period in a not uncomfortable cell and who is told one morning, “Now, then, you’re going to be let off today. Here’s a little money for you. Now clear out”.[29]

In a large city that still makes her feel that its lights are like ‘cold, accusing, jaundiced eyes’, alcohol brings a semblance of warmth that seems to mitigate that ‘cold’:

The waiter brought the Pernod she had ordered and she drank half the glass … Warmth ran to her face and her heart began to beat more quickly. / … A heat which was like the heat of rage, filled her whole body.[30]

We are back to the dialectic of binary warm and cold here but its tentacles reach to the infernal heat of rage. These rages are like the ‘violent ingratitude’ in Rhys that Cooke reads in Seymour’s biography of the artist that she cannot understand. But surely Seymour shows us that this is precisely how Rhys survived incorporation into the world of English repression and womanly ‘passivity’ that could not even begin to rebel. The rebellion may never have been more than symbolic and maybe the only base it touched or saw was the base of a whisky glass but it was in a way effective in getting through and staying with countless poor marriages or alliances, risking becoming the bad mother and ungrateful friend she feared she was and which, let’s face it, she very definitely succeeded in being, amongst other rare and relatively short-lived moments of love and caring. For to be bound to love and caring is to become Julia’s sister, Norah, a woman society absorbs and then spits out like a hardened pip, once she has finished being the carer of a comatose unloving mother and given up all hope of the return of love.

In her Green Exercise Book in 1936, Rhys may have thought the outlet of hate a weakness of will caused by alcohol but I wonder whether the weakening of will was, she might eventually realise, the only motivation she had to necessary rage – even where she chose the objects of her rage poorly and inappropriately: “It is only lately that I answer unkindness with a raving hate – because I’ve got weaker. My will is weakened because I drink too much”.[31] By November 1996 she told her long-suffering daughter that “Whisky is a must for me now”.[32] You cannot it seems be primarily involved in the care of others or in loving significant others when drink is your one necessity but perhaps drink also frees you from the search for security in the status quo and enabled Rhys to return to some of the issues of resistance to racism, sexism and the marginalisation of the neuro-different under the label ‘mad’ that was a theme of her life and which at times caused her incarceration in prison or asylums for ‘her own good’.

Miranda Seymour’s book is a treat but it is an even greater treat to let Seymour hold your hand back to an intelligently restless and non-institutional non-academic liking of her novels.

All the best

Steve

[1] Miranda Seymour (2022: 312) I Used To Live Here Once: The Haunted Life of Jean Rhys London, William Collins Publishers.

[2] Claudia Fitzherbert (2022) ‘She Went Down Well with Vicars’ in The Literary review (Issue 507, May 2022) 30-31.

[3] John Walsh (2022) ‘Whisky and lots of sex’ in The Sunday Times [Supplement] (24 May 2022)

[4] Rachel Cooke (2022) ‘I Used to Live Here Once by Miranda Seymour review – the troubled life of Jean Rhys’ in The Guardian – online (Mon 16 May 2022 07.00 BST) Available at:

[5] A.L. Kennedy (2000:161) ‘Afterword’ in Jean Rhys Good Morning Midnight Penguin Classics ed.

[6] Jean Rhys (2000: 31) Good Morning Midnight Penguin Classics ed.

[7] Ibid: 14

[8] Miranda Seymour op.cit: 178

[9] Rachel Cooke op.cit.

[10] Good Morning Midnight op.cit: 27

[11] Miranda Seymour op.cit: 179

[12] Rhys cited in Carole Angier (2000:161) ‘Afterword’ in Jean Rhys Voyage in the Dark Penguin Classics ed

[13] Jean Rhys (2000: 56f.) After Leaving Mr Mackenzie Penguin Classics ed

[14] Jean Rhys(2000: 24) Voyage in the Dark Penguin Classics ed

[15] Ibid: 28

[16] Jean Rhys (2000: 109) After Leaving Mr Mackenzie Penguin Classics ed

[17] Joseph Conrad’s Almayer’s Folly quoted ( a full paragraph) ibid: 84.

[18] Claudia Fitzherbert op.cit.

[19] Seymour op.cit: 138f.

[20] Carole Angier (2000:160) ‘Afterword’ in Jean Rhys Voyage in the Dark Penguin Classics ed

[21] Jean Rhys Voyage in the Dark op.cit: 135

[22] Claudia Fitzherbert op.cit.

[23] Rachel Cooke op.cit.

[24] Seymour op.cit: 320

[25] Good Morning Midnight op.cit: 36f.

[26] Seymour op.cit: 31

[27] Jean Rhys Voyage in the Dark op.cit: 143

[28] Seymour op.cit: 149

[29] Jean Rhys (2000: 11) After Leaving Mr Mackenzie

[30] Ibid: 13

[31] Cited ibid; 169

[32] Ibid: 291