Alan Hollinghurst, in an introduction to the book detailing the current retrospective exhibition of the work of Glyn Philpot at Pallant House, Chichester, says that the ‘cumulative impression’ he has taken from knowing the artist’s work is of Philpot’s ‘masterly conformity in lifelong tension with the disruptive and innovatory force of his sexuality’.[1] This impression needs to be modified by a concern with his interest in ‘the exercise of power’ more generally in human interactions and established relationships.[2] These relationships include amongst others those between master and male slave/servant and between hierarchically configured relations between races. This blog reflects on the 2022 book by Simon Martin, ‘Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit’ (Chichester, Pallant House Gallery).

Any discussion of the ways in which human beings shape, maintain, cancel and re-shape relationships between them cannot even begin without acknowledging dynamics of power that are sometimes pre-structured into those relationships and at other times seem as if they have to be forged in order to make a relationship possible. My take on how these phenomena arise in art (drawn, painted or sculpted) has limitations based on never having seen any of the works ‘in the flesh’ that I here discuss. I would love to see this particular retrospective exhibition (a labour of love by the committed queer curator, Simon Martin) to make good this absence. However, the expense of travel from Durham to Chichester will probably make this impossible. But let’s see! The necessity of seeing the original rather than photographically reproduced works is underlined by the massive changes in Philpot’s artistic methods throughout his career. Most notable of these changes is the move from techniques involving the layering of paint (and sometimes colours) to create textural effects in his paintings. In later works there are thinner surfaces, where brush marks achieve visual depth only by virtue of adjacency on an under -painted or unevenly painted surface. He expressed this change to art historian R.H. Wilenski by saying he had once:

… built up my pictures with underpainting, as the Old Masters did, and then worked the colour with successive glazes, and then covered the whole thing with a glaze of varnish, mixed with ivory black or sienna. Now I use no glazes at all. I do not aim at a rich surface.[3]

Such effects can be appreciated by reproduction of extremely high resolution (as I saw in the Van Gogh experience exhibition in Salford – see blog). However, such technology is rarely used. And, of course, it still cannot trump seeing the paint fleshed out by haptic sensation that only the presence of the material artwork can produce. A major retrospective at Pallant House, Chichester is the brainchild of its curator, Simon Martin, who has championed not only the neglected innovations of early and mid twentieth century art but also the queer curation of the art of queer painters. That does not mean that this art, and Philpot’s case is exemplary here, needs to be seen as ‘politically radical’, for Philpot was in many ways a pillar of the establishment in terms of the status quo’s distributions of power in terms of social class and gender.

As a curator Martin has championed achieving change in public attitudes about art (and through art in the psychosocial world it addresses as its subject-matter) whether directly or, more clearly in Philpot’s case, indirectly. He has called his method ‘programming by stealth’ and ‘quietly radical in its thinking’; aimed at clearly acknowledging and articulating ‘homoerotic content’ and increasing ‘the visibility of artworks that might be deemed ‘queer’’. The ‘might be’ is an important qualification here since it acknowledges that queer themes can be disguised by strategies of very different kinds and that acknowledgement that a theme or its method of delivery can sometimes only be seen as ‘queer’ by those who are not more thoroughly programmed to interpret it through powerful external norms. The ‘stealth’ involved in ‘programming by stealth’ is that, Martin argues, it promotes normalizing difference, such that our view of art is no longer homogenised and (to coin a word) heteronormalized.[4] That means that this exhibition required an interpreter who was sensitive to indirection of approach and to the intersectional nature of a truly queer approach to the representation of difference across issues such as class, gender and race and perhaps – and this is truly radical – the norms of what is considered beautiful. What particularly matters in Martin’s background is his grounding in what he names ‘critical race theory’ in the preface to the present book and how this concept is applied to the study of the dynamics of the artist’s relationship to models, which is too often both heteronormalized and drained of the problems it presents in terms of power relationships.[5]

The unusual (for the white Western non-narrative art of the time) frequency of images of black people in Philpot’s painting is referred to in the reviews of the exhibition with varying degrees of openness to the issues of power involved. Thus in The Guardian, Hettie Judah says of Philpot’s relationship to the main black male model of Philpot’s from 1932, Henry Thomas:

Philpot’s favourite Black model was a Jamaican-born man named Henry Thomas. Thomas worked with Philpot for eight years, sitting for him until a few weeks before the artist’s death in 1937. At first he was paid a retainer: later he joined Philpot’s household in a combined role as model and servant.[6]

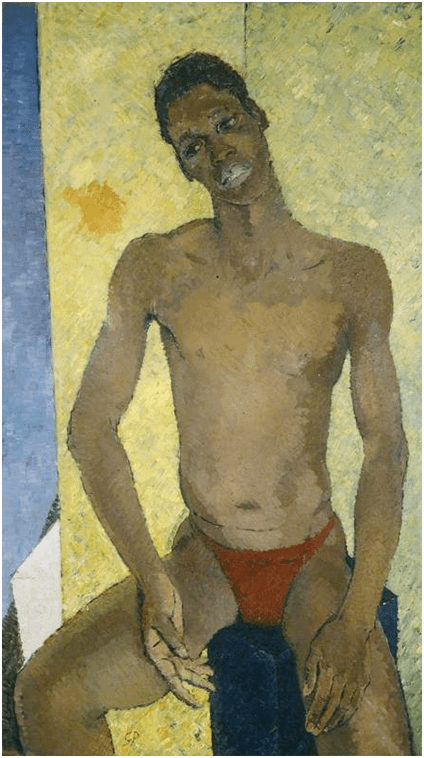

About the power relationship between Philpot and Henry Thomas, Nicola Coleby and Jenny Lund, writing in 2019, have a fuller description, which posits that painting black subjects enabled, because they were themselves seen as ‘other’ to a white Eurocentric norm, white artists to portray a more open image of queer sexuality. Thus writing of the portrait below, they say:

… Henry Thomas’s long torso and limbs are accentuated and the tilt of the head and the open arms and hands suggest a passive gentleness, the gold background accentuating the sensual rendering of the model’s skin. The blue strip at the left gives depth to the painting and makes solid the figure in space. This feminised, languorous portrayal of a black male hints at Philpot seeing black men as ‘other’, onto which he could project a coded homoeroticism otherwise difficult in the censorial society of the 1930s.[7]

Coleby and Lund may, in my view, stretch a subjective view to its limits for I would question the degree to which Thomas is ‘feminised’ by ‘passive gentleness’, rather than say, ‘infantilised’ (a more likely effect). However, both readings are contradicted by Philpot’s emphasis on Thomas’ exaggeratedly large hands in contrast to his slender boy-like body. However that he uses Thomas for his own artistic purposes, as an image of his own projected desire involving some degree of both identification and objectification, is possibly the source of the ambivalence of the image between passivity and a suggested readiness to act that I sense in those hands. It is difficult I think not to see some degree of racism and class-based oppression in such a scenario where black bodies exist mainly as a projection of white male desire, whatever the sex/gender of the desired, which if Colby and Lund are correct is ALSO projected from male fantasy. Simon Martin does not stand back from the debate but handles it with a different kind of nuance; especially in Chapter 6 which focuses on Henry Thomas alone. He sees this painting as showing ‘a strong sympathy for the social outsider’, locating excitement not in the possibility of a sexualised male body presented to the male gaze but to the ‘technically exciting’ quality in the handling of the paint.[8] I find this view troublesome in that it rather oversimplifies the object of queer desire by failing to see that the excitement conveyed by innovative paint handling is not exclusive of the desirous excitement of touching the flesh of a desired person and can convey the haptic sensation of the stroke and the dab in both activities. Moreover, ‘strong sympathy’ might exist alongside conscious or unconscious desire, whether this posit communion as sharing or possession, for human beings are complex agents. Nevertheless it is important to see the grounds for the propagandist altruism that might have motivated Philpot. Martin locates that possibility in the possible knowledge of debates about black representation from the Harlem Renaissance including the ideas of W.E.B. Du Bois in Criteria of Negro Art of 1926. Du Bois posed a challenge to art by white men that aimed to portray black men. Du Bois says in his essay:

…, the white public today demands from its artists, literary and pictorial, racial pre-judgment which deliberately distorts Truth and Justice, as far as colored (sic.) races are concerned, and it will pay for no other.[9]

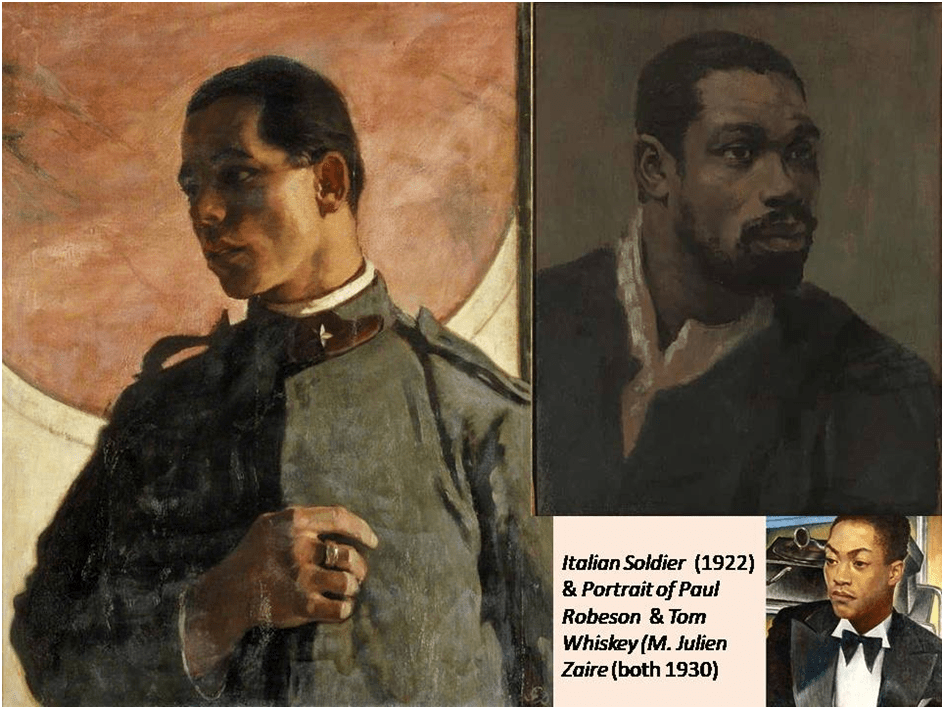

One means of pursuing a black-person-friendly representational agenda was to portray successful black professionals including creative artists: Philpot clearly did this in portraying military heroes, such as his Italian Soldier (1922) and creative artists such as Paul Robeson as Othello, painted in 1930 and the ‘refined figure, wearing a dinner jacket and black tie, at home in a modernist interior’ and Bauhaus style furniture of M. Julien Zaire (Tom Whiskey) in 1931-2. Nothing is further from the stereotypes of black men (criminal and / or ‘stupidly good’) found elsewhere in white culture.

It is posited by some that even stock work bearing the image of Henry Thomas would seek to put him in positions of power, such as the 1929 image of him as Balthazar, bearing a nativity gift to Christ, which elevated him by the richness of apparel, the skill and variety of colour and aristocratic bearing that remains human and the showering of eternal grace that surrounds his head as a reflection of Philpot’s Catholicism (see below).

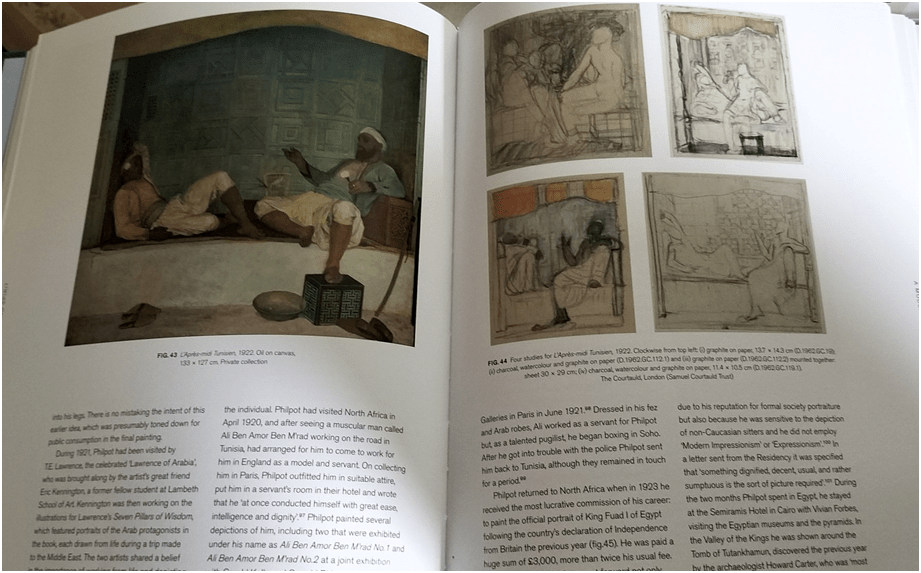

Nevertheless, it is also possible to read Balthazar as an example of an image of male beauty that is entirely ‘othered’ using classic tropes of the Oriental other in order to be seen as offered up (like the Nativity gift he bears) to the viewer sexually, in which the apparel is not a sign of riches but of a beautifully wrapped present, which is already being opened up to the viewer in a manner that invites closer haptic intimacy with complexly textured painted naked skin. The eroticisation of black naked skin made optically available is as evident a meaning in representations of Henry Thomas as is the richness of a more refined image of the black male. The two co-exist in varying degrees in simultaneous relation to each other depending on the artwork examined and the use of race characteristics to sexually as well as racially other the viewed subject male body. This phenomenon appears frequently throughout Philpot’s career in, for example, his fragmented body sculptures and in clear examples of Orientalism used to sexualise the subject, as much as does the harem when used by Ingres. Martin brilliantly analyses for instance the painting of 1922 L’Après-midi Tunisien and the various prior studies of that subject (in which the two male participants are placed in different degrees of proximity to each other’s bodies and wherein ‘there is no mistaking the intent’ of depicting ‘hints of homosexual flirtation and bodily contact). Indeed Philpot apparently expressed an almost sociological interest in such relations amongst the Maghreb people like that of T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia) and possibly with the same agenda. Both mirror the same theme in André Gide [10]

The virtue of Simon Martin’s book is that he describes all of the historical-theoretical resources required to analyse different interpretive stances of Philpot’s interest in black male bodies. In doing so, he never forgets that such images are as much about the regulation of interpersonal and structural power dynamics as well as queer sexual exploration in search of ‘a “legitimate” manifestation of queer desire in mainstream visual culture’.[11]

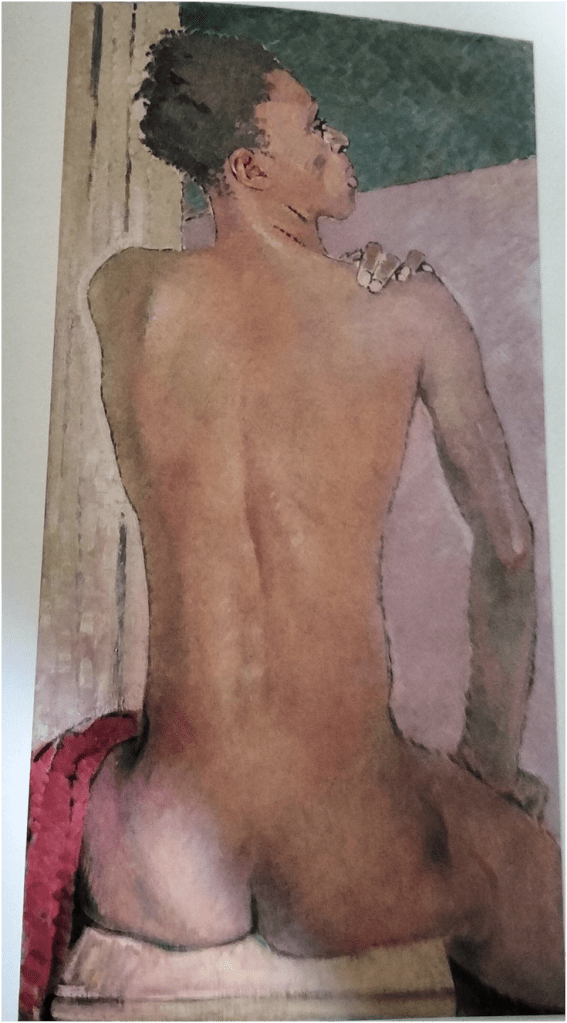

Sometimes I find the handling of this latter theme somewhat strange but it does illustrate the rather programmatic way in which the censorship of images of male sexuality occurred in Britain particularly around the censorship of full frontal nudity and the visibility of the penis. In discussing Henry Thomas Sitting – Back View (1937), Martin points only to it as evidence that he was ‘scrupulous about avoiding a full frontal view’, as if avoiding representation of the penis was alone a negotiation with full sexual openness (not only in him but also the model of heterosexual orientalism from Ingres that he evokes as an influence on Philpot).

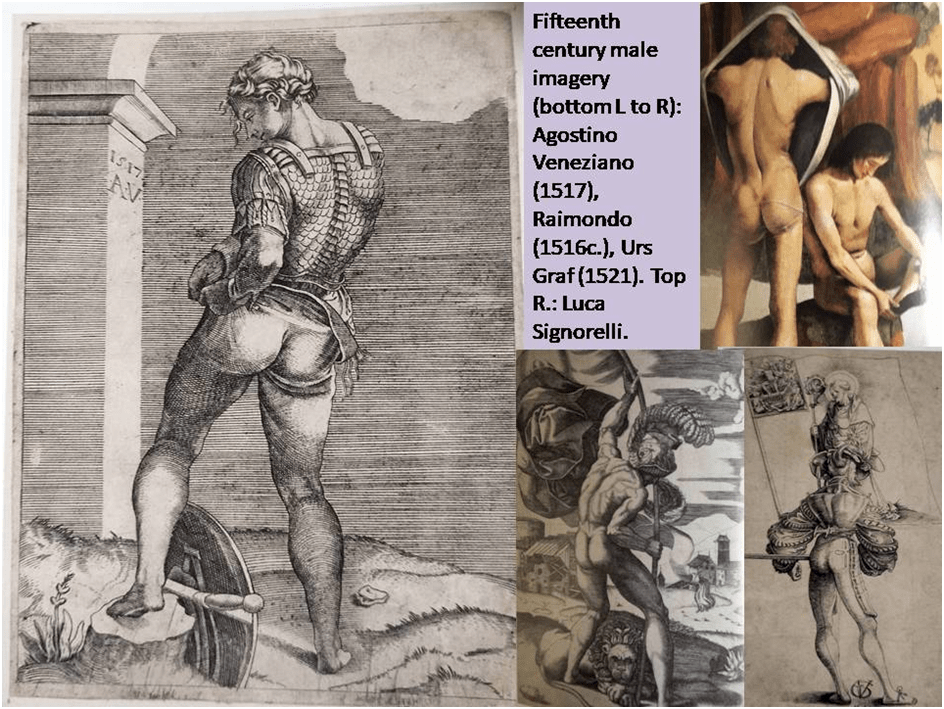

This surprises because the tradition of eroticising the posterior view of a male figure is much older than Ingres’ female paintings and was not always confined to, or (as some might say) masked by, merely aesthetic ends. For instance, according to Patricia Lee Rubin in her magisterial 2018 book on the representation of the male body in the fifteenth century, showing off ‘tightly built bodies’ was, in prints and paintings containing soldiers (often of religious subjects such as martyrdoms) in part aided by a change to ‘more tight-fitting’ military costume in the fifteenth-century. She argues that, whilst ‘enjoying these images, it would be difficult to ignore the attractions of such firmly rounded bottoms, their volume accentuated by the deep shadows shaping them’. These views cannot be accounted for merely as a reflection of the sexual identity of the artist, the strategy used for determining, for instance, the sexuality of a nineteenth-century painter like Gustave Caillebotte (which I have discussed in earlier blog, one early one on Caillebotte and another more generally about depicted images of males and invoking Titian (rarely, if at all, described as homo-erotically inclined). In prints male ‘bottoms’ were significantly often, she shows, accentuated; by being pointed to in a 1521 by Urs Graf design for the banner of a Swiss canton or by position in the design such as being ‘at the centre of the plate’ in Agostino Veneziano’s 1517 engraving, after Michelangelo, of a Soldier Fastening his Leggings or Luca Signorelli’ fabulous 1488-9 painting Figures in a Landscape: Two Nude Youths.[12]

Returning from the Italian Renaissance images above to Philpot will at least remind us that posterior views are not a disguise for a sexual interest in the male body and that some of the same means of eroticisation are used by him as in them, particularly variegation in shading and darkening, textural play in the paint surface and geometric positioning. What is beautiful in the painting is that some of these effects are mimetic of the effect of the pressure of objects on flesh, such as the enormous care Philpot gives to the cusp of Henry Thomas’s anus and the soft seat on which he sits and the effect on his inner musculature of the spread of his legs. Of course, all of these effects are made more complex because Philpot is directing our gaze onto black skin, whose eroticisation (to the eyes of a white audience) is clearly evident I do not know however how this relates to the stress in this painting on the achieved perception that the colour of skin is itself an effect of contextual lighting and contact with properties in the scene, even tonal contrasts. The ‘racial’ physical characteristics are borne entirely it seems by the backward glance of Thomas’ face which affords a facial profile emphasising his hair and lips and that beautiful self-caress of his hand.

As I think and write about Philpot’s white queer gaze on the black body, I remain with Simon’ Martin’s insistence on the nuance in Philpot’s representations of black men that it can be both positively intended and yet have a negative effect in the context of structural oppression around ‘race’. I would still however question Martin’s insistence that representations of the black male is used such as to ‘other’ in sexually objectifying ways by feminising it in the manner discussed by Linda Nochlin in her phrase ‘the original Oriental backview’ to describe Ingres’ Valpinc̗on Bather. Male bodies are rendered complexly sexual, I would argue, in many more ways, than those even if not excluding those that evoke conventions of the representation of binary sex/gender.

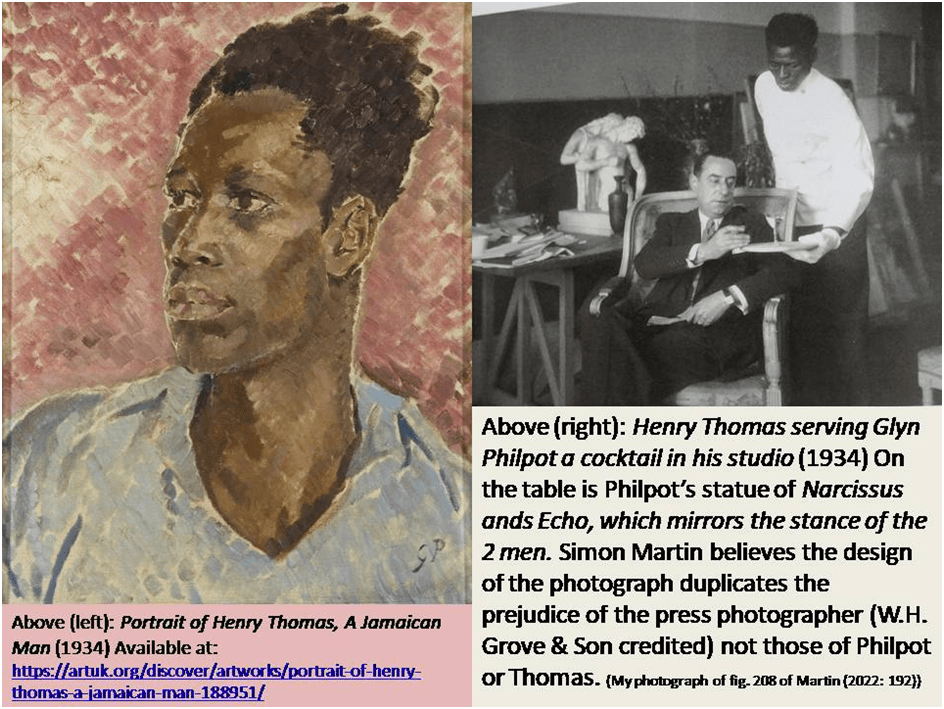

There is much more to say about Philpot’s representation of black men in the context of the huge social difference between him and the models he used, especially the tragic story of Henry Thomas following Philpot’s death. But Simon Martin does, I think, provide all the ways in to that debate and the historical-theoretical resources needed for it, as I have already hinted. A perfect example of this in the context of Philpot’s very privileged life and the relative poverty of his models is cited from Kobena Mercer by Simon Martin. It emphasises the massive quantity of white cis male and social status based privilege to which Philpot felt entitled next to the absence of these in his paid models. I cannot get beyond this contradiction and believe it must be seen as fundamental and problematic in our appreciation of Philpot’s art, but not always in a negative way necessarily. Writing of the obvious admiration of Thomas’ beauty of face and profile in the 1934 Portrait of Henry Thomas, a Jamaican Man (see below), Martin says:

Kobena Mercer has written of how “knowing the artist’s model was also his servant, presents us with a challenge’. He continues: “On the one hand, Philpot brought an enormous attentiveness to his portrayal of Thomas that completely went against the grain of the master / servant relationship in the colonial era.

But on the other hand, to notice that Thomas never looks back, for his eyes are always averted, is to recognise that we are surely not among equals”.[13]

Of course, although averting one’s eyes from the other is a signal of perceived inequality of status, the inequality may be interpreted as either a sense of one’s superior in social status or an internalised inferiority. It is not enough evidence in itself of the particulars of the power dynamic governing Henry Thomas in Philpot’s household as model and servant (paid as he was in one combined salary). Nevertheless, he leaves the viewer with the central contradiction, which is, I think, that both may be intended rather than it acting as a mask of a meaning in one direction or the other.

However, the discussion of the signalling of power dynamics vis-a-vis the artist and their models and / or figural subject (for these are not always the same even in a portrait) is widened by the discussion on issues of race. This discussion includes consideration of the white gaze which others its black subject as a means of using them for expressing a projected transgressive desire. This is a theme Alan Hollinghurst emphasises in the words I use in my title: a ‘masterly conformity in lifelong tension with the disruptive and innovatory force of his sexuality’. [14] In my view this phrase contrasts Philpot’s passive acceptance of the status quo of unevenly structured social powers implied by his apparent comfort in his own privilege as defined by his class, gender, ‘whiteness’ and enablement to something disruptive implied by queer desire. I want to test this in looking at Simon Martin’s arguments.

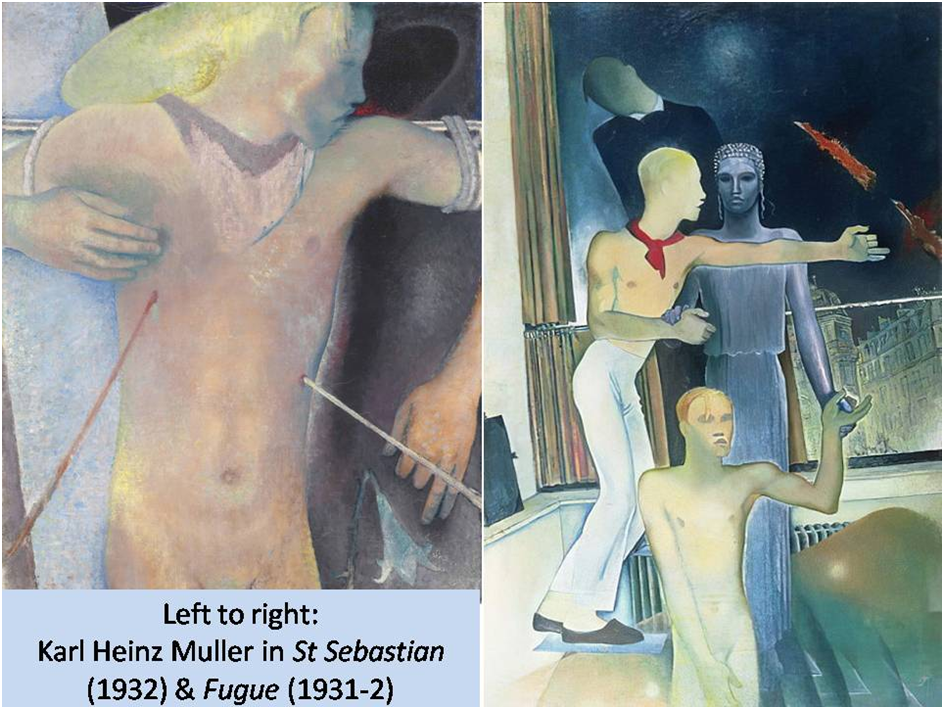

Philpot like Auden, Isherwood and Spender exploited classes vulnerable to such exploitation and particularly in obtaining sex from kept young men in Berlin in the 1930s. In looking at this I start, first of all, with Philpot’s version of the St. Sebastian motif; for on this iconic image hangs an important debate about queer desire. Martin cites the importance of this image not only in Roman Catholic (and particularly Counter-Reformation) art but to the newer iconography (discussed by Martin in the thought of Magnus Hirschfield who claimed that pictures of the saint were amongst those ‘in which the “invert” takes special delight’). Richard Kaye in 1996, as cited by Martin, took this further into the realm of purely visual culture by seeing in the icon access to a distinct ‘homosexual identity’. This identity was not constituted by ‘homosexual acts’ but by ‘a desire or taste in beautiful men’ equivalent to ‘a homosexual sublime’.[15] According to Martin, Julia Kristeva named his typification of the untouchable (but forever available (to the aesthetic eye) image of male physical beauty as the ‘exemplary “soulosexual”’.[16] In this light I think the view of Robin Gibson in 1985, in the catalogue of the first ground-breaking Philpot retrospective in the National Gallery London, is nearer to the mark of what is implied by pictures like this and Fugue. He says that these are ‘experimental pictures’; that have each their own ‘imperfections’ but which ‘nevertheless have the authentic ring of personal and creative struggle’. Had these qualities been developed, he says, they would have made him more certainly a great and not just a skilful and talented painter.[17]

But, though Martin does not explicitly tread this route, I think he gives us the tools to get beyond the idea in Gibson of Philpot being the solitary fallen angel of a sublimated gay identity. Though a ‘holy’ image, Sebastian’s isolation conflates identity with his tragic destiny. In looking at St. Sebastian I see struggle and conflict of power, rather than just passive suffering, being emphasised. The hands and arms struggle for freedom from the implements of torture which resemble the underwhelming props available in the scenarios offered by a modern Berlin flat of the 1930s. The lateral pole to which his arms are tied is a curtain pole (said to be, with its reappearance in Fugue, based on one actually in the Berlin flat to which Philpot invited the young working-class ‘model’ and damaged lover, Karl-Heinz Muller. The latter is identifiable because of the lost end sections of two of his fingers ends on his left hand.[18] What strook me in the picture at first as representations of the arrows shot by his fellow centurions into Sebastian’s body later look as much as if they are being ejected from his body like a stream of blood and light respectively. For as well as positioning the figure between, on the one hand, a struggle to be free and, on the other, passive acceptance of his enforced containment and death (since the painted face is a kind of darkened death mask).

The style of the painting saccades away from a realistic evocation of flesh in paint in the torso and upper groin as it fades into its upper and side margins. At the bottom of the frame the base of his penis propels the eroticised gaze beneath the picture frame but is never other than suggested (the same happens in Oedipus and the Sphinx). Next to this dynamic is the representation of a lily like that in traditional Annunciation pictures figuring Mary’s chastity (and perhaps Wildean aestheticism). The important thing here is the dynamic of the pulls from appreciation of hard gemlike beauty and something more fleshly demanding haptic sensation. Sebastian’s hair and his neck are, in contrast to his torso and upper thighs, painted with near ornamental abstraction. The thick brushstrokes forming the suppressed figure of a bird or angel at his neck could be an ornamental collar but it also is a means of severing the figure’s head at the brown rough cut from the body. Pastel-like colouration (it is oil paint nevertheless) disrupts smooth erotic flesh in ornament and ambiguous suggestion of objects emergent from a fictive background.

My preference is to see Philpot as, even if not intentionally, locating queerness in its resistance to being turned into one simple type/stereotype. This is what I see in that beautiful use of Muller as a model in Fugue. Muller’s image is here continually duplicated and, in some ways metamorphosed in each image. The meaning for me is that the capacity of humans to find possible alternative forms of being displaces questions of a singular ‘identity’ with a beauty embodied dynamically very act of multiplication of selves (see collage above). This locates beauty in resistance to rigidity and normativity, like Sebastian fighting the rigid curtain pole that attempts to hold his body rigid, a curtain pole that also forms part of the background in Fugue. The rigidity is also shown in the pale goddess who in various ways holds the three appearances together but only such that they can be differentiated from her. Martin guesses that her form, which is that of a kore, is possibly Artemis or Athena, to whom such statues were often dedicated in Archaic Greece. Martin then supposes her, if she is the latter, to represent self-knowledge. For me such long shots are unnecessary in that the kore is a representation of death and mortality, used as a grave-marker often in Archaic Greece. Men like Karl, and perhaps Philpot both resist and seek identificatory solace with death, perhaps as a marker of self-knowledge, to which the dressed and faceless Karl behind her has, perhaps, no access. I cannot at all defend this interpretation as other than personal but I do not think it could be improved by knowledge of Philpot’s intention; for this is an art that questions everything and solves nothing.

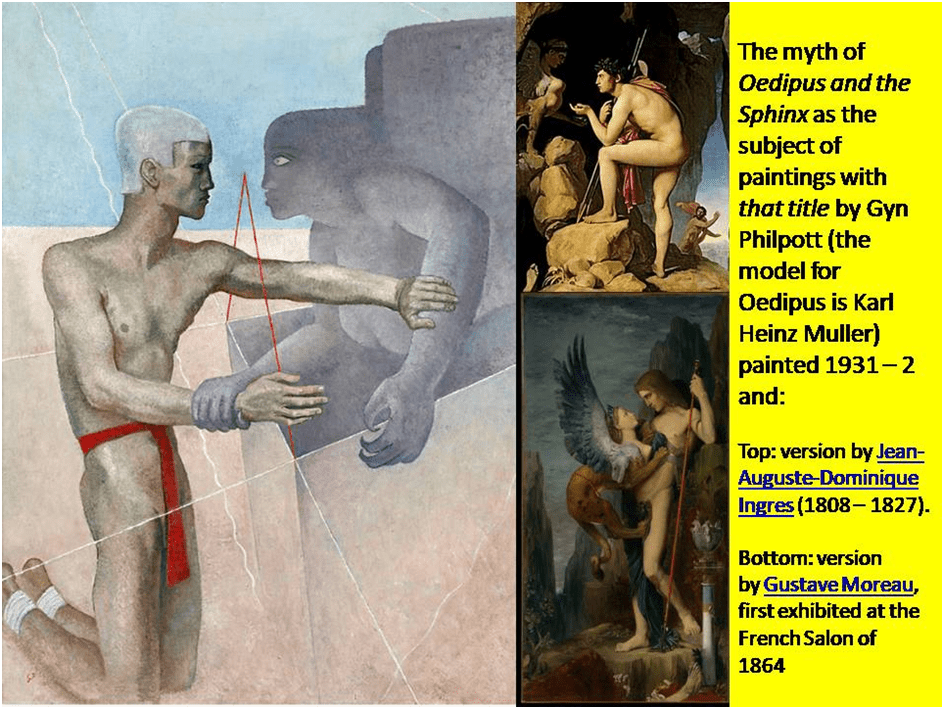

I think the import of another painting for which Karl modelled, Philpot’s Oedipus and the Sphinx of 1931-2 is similar. For this is an art that refers to a trope to be found in a Neo-classical painting by Ingres and its parody in Gustave Moreau. For this reason I place the pieces in proximity in a collage below:

I need to repeat myself – possibly not for the first time – that I believe that Philpot’s ‘is an art that questions everything and solves nothing’. In a sense this meaning lies is the narrative function of the Sphinx in all these artworks with that title, if not as intensely as in Philpot. In each Oedipus is caught mid question and answer with the Sphinx, whose entire set of two possible riddling questions are about providing a unitary answer (one name) for something which is multiform. In the first man’s life is the solution of multiform stages (four legs, two legs, three legs) , whilst in the second, it is diurnal time with two stages (night and day). But in both the Ingres and Moreau, Oedipus masters the Sphinx not just by giving the right and authoritative answer but by turning the Sphinx back into the suppliant woman she need to be for him to be master of her, Thebes and what he thinks of as his Fate. In the Ingres painting Oedipus eyes are raised in such a way that they take in those of the Sphinx by levelling himself at her breasts. Soon he will rise to authority over her. In Moreau he already has that position and, even as she thinks she is in command, she is subjugated into becoming the bridge between Oedipus’ eyes (to see which she must look up) and his penis. She is, after all, reduced to the size of his torso. In both cases, the classical nude male asserts the right to control of the feminine through his classical beauty and superior posture.

This isn’t the case with Philpot where the sphinx is in dynamic struggle with Karl / Oedipus. He resists her claw-like left hand by active pushing back against it, even though she seems to have him in her grasp with her other hand. Their eyes meet at the same level and Oedipus kneels so that this might be the case: both are locked in puzzles without resolution. Indeed, Philpot shows that by organising the formal flat space of his canvas geometrically that he is in control of problems of surface and depth, especially with the suggestion of a pointing hand towards cubism as a means of reconstructing the space of the painting between depth and surface. I see the latter in the fact that the eyes of the combatants meet at the apex of a triangle that is flat and not even attempting to be pyramidal as the oblong forms to its right strain to become cubes supporting the sphinx’s body. And amongst the questions here are ones about the sex/gender of the combatants. It is clear in the picture that Karl has a phallus, though it is partly concealed by his loin-cloth, but this sign does offer him command or authority in itself over the sphinx in acts that dominate her, as if by a sex act. It is an art about the means of its own construction, with the hands in a phase of active making of the sphinx as a sculpture but a sculpture that retaliates to ‘make’ the artist or try to make him.

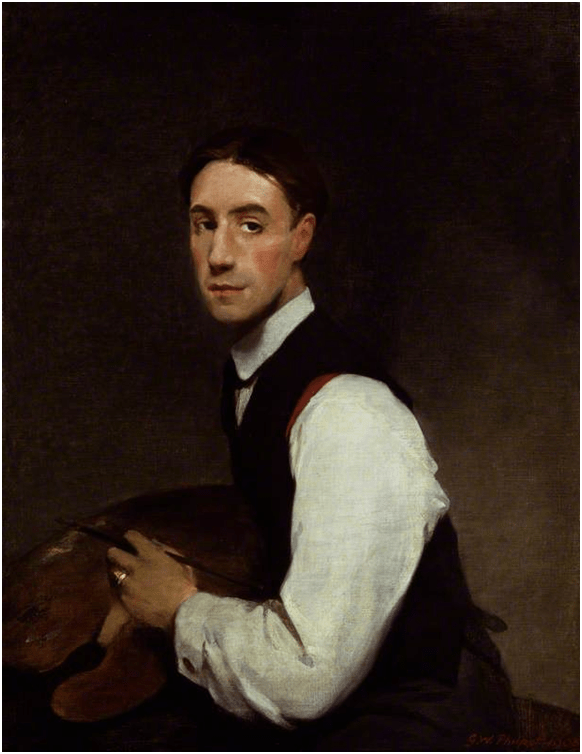

Indeed I sometimes think Philpot’s life-work is an example of meta-life-in-art, art about the nature of the art of a developing individual in a developing context, including artistic modes and movements like Cubism, and the monumental ‘realism’ that succeeded that in Picasso’s career, for Picasso was the model against which to test one’s art. To get to that position I compare the Oedipus and the Sphinx as a critical makeover of neoclassical and Romantic art to the assured and skilful but rather intellectually null early self-portrait of the young man as artist.

It’s a beautiful portrait of an earnest man and his gaze captivates its audience as both Oedipus and the Sphinx do each other in Philpot’s version, but it is also mannered and, like the work of an actor, not so much a portrait of the artist but of the artist performing as an artist. His gaze is at us as if we were his model and the scrutiny is caring rather than judgemental, although not slavish. The pallet and brush he holds seem rather to make us admire his earnestness rather more than look for him to use it in our service. It complements a stereotype of what painters do rather than makes us believe he is going to complete a task to our needs. We are literally held in a moment that will never come – one where the artist only sees himself, and it may strike us that the reason for this is that he is looking at a mirror. There is no tension here or resistance to the conventions the painting itself represents – of an artist fulfilled in his task without reference to another world.

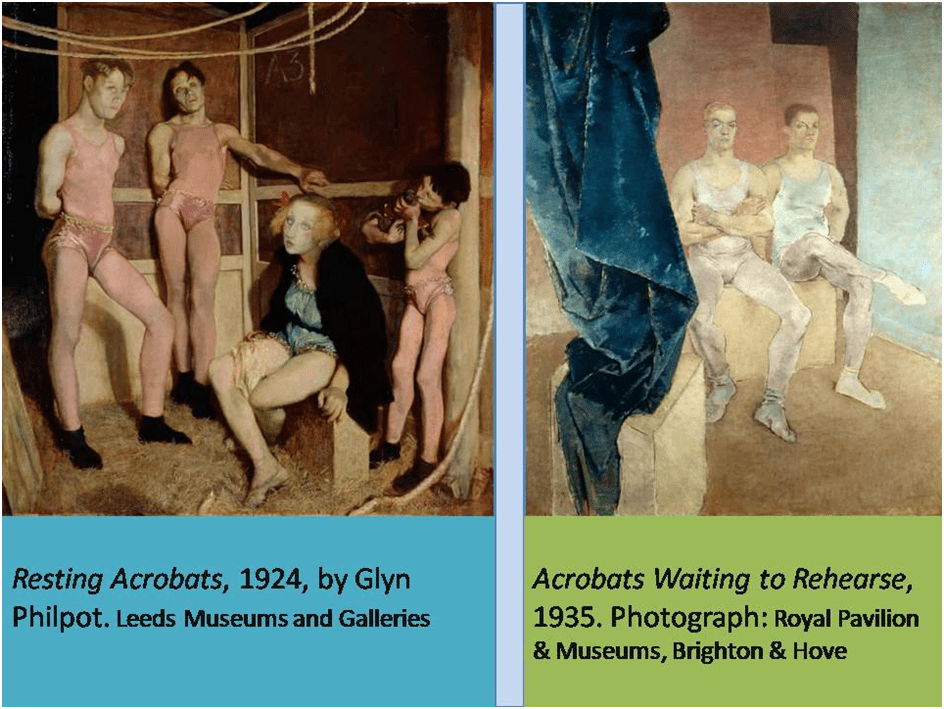

I want to speculate here and to assert a strong personal conviction that there is something of the magician about the convention of the artist who entraps the gaze of an audience and focuses its on his own powers without explanation of their process, as if they were supernatural, as Prospero does in The Tempest. The later Philpot works, such as Oedipus and the Sphinx make us aware of that entrapment by making us aware of its process being constructed by the craft and labour of the artist. But the reason I speculate thus is actually to try and explain to myself why he created such powerful mid-career paintings that seek to go behind the apparent magic of the visual scenery of visual art. My guess is that they conceptualise an artist’s ‘power’ as something that, if it exists at all, exists because it has been manufactured by hard labour of the embodied brain, heart and hand of a person who is, at some level, working on a task. As I speculated in this way, I began to see that this is why he turned to representing jobbing ‘Artistes’. These studies of apparently unstudied dejection show that the work of the artist when seen behind the ‘scenes’ is a long way from the earnest image of the relaxed man in Philpot’s only self-portrait. For a lot of the work in a work of art is in these pictures shown to be unglamorous.

Although fascination with the image of the performer and entertainer was not unusual in twentieth century art (not least in Picasso), the deliberate evocation of the artifice that made up a painted ‘scene’ is fundamental to the conception of art in the examples above. This is so especially in the way we see the cube-shaped block on which the blue curtain rests (indeed it almost sits on the block like a figure). We see that ‘cube’ as strange and distorted and not in perspective relative to other objects and figures near to it. The effect is to make this feature seem as if it were an element lifted from an experiment in formal Cubism. In this 1935 painting the stage sets are also more notional and abstract suggestions of scene ‘flats’ as if also referencing the use of abstraction in painted art whilst the scene flats are wholly realistic in their sturdy wooden geometric frameworks in the 1924 example, so much so that one of the acrobat figures rests his weight on them. Whilst Resting Acrobats makes room for ‘play’ in the figure of the child, the adult figures therein express the exhaustion of their endeavours to artlessly please an audience of which they are no longer thought to be aware. In every respect, although the figures can look artlessly beautiful – as in the parody contrapposto pose of the figure in the painting on the viewer’s left, they are not conventionally beautiful: the silks worn look uncomfortable on the figures and the figures’ faces are almost dejected behind their make-up, perhaps overmuch so in the female figure.

My best guess at making sense of these pictures is that they stress the tension of work either in its resting interstices or in preparation – the fact that the body’s beauty in dynamism, whether in wielding an artist’s brush, or making pleasing and unexpected shapes with one’s whole body in space as an acrobat does, is an act of labour by a figure (the artist) who is in fact marginal to our pleasure. At least we can say that the working body of the artist themselves is marginal to our pleasure whatever our delight in its products (apparently produced out of nothing but in fact gross materially manufactured images. It is at this point I will return to how Philpot’s art was transformed in his later work.

What Hollinghurst suggests is that the realities of Philpot’s need to acknowledge somewhere the disruptive awareness of his embodied sexuality caused innovation in his work. And it caused innovation because he no longer felt his role was solely to create ‘objets de luxe for drawing rooms’; the drawing rooms of the rich establishment of which he was part. Rather he now represented life at the margins of what the normative status quo, and its stakeholders, felt to be acceptable. These ‘unacceptables’ were outcasts, the working class, Eastern or Southern racial figures and the temporarily or even permanently damaged whom are seen as ugly (indeed Resting Acrobats makes a thing of beauty of faces resting into ugliness). He expressed this, when interviewed by art historian R.H. Wilenski, as a means of becoming as an artist ‘more interested in “souls”’. Philpot himself says his work changed because ‘”new modes of expression are continually necessary if the artist is to add to the sum of beauty in the world”’.[19] Simon Martin is really useful in this respect because he introduces perspectives from wider cultural history, in order to explain contradictions in Philpot’s position which made his marginal (and publicly unspoken) position as a sexual being disruptive of established norms in art and sentient life. Below Martin speaks of the sexual passion for working class boys who were also damaged, but beautiful ‘foreigners’ boys like Karl Heinz-Muller, in the case of Christopher Isherwood, who also had sex with Karl (at least when Karl wasn’t suffering from a “nasty dose of clap”):

Isherwood’s explanation of his own situation may have resonance with Philpot’s relation to his own models: he was suffering from an inhibition, then not unusual among upper-class homosexuals: “he couldn’t relax sexually with a member of his own class or nation. He needed a working-class foreigner”. Such an upper-middle-class fascination with crossing the class divide does not merely suggest what Jeffrey Weeks termed an “avidly exploitative sexual colonisation which marched counterpoint with the dream of class reconciliation”, but also a sense of identification with that very otherness. It was Philpot’s acknowledged status as outside the heterosexual norm that perhaps led him to identify with social outsiders: Black models, working classes and the foreigner.[20]

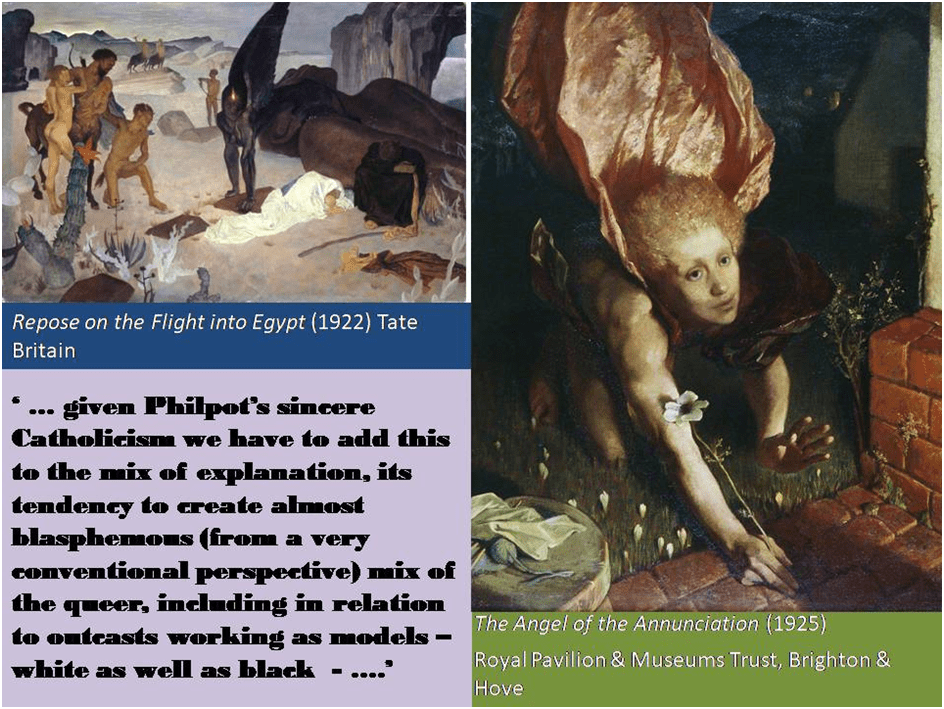

I find this explanation convincing as a means of understanding the contradiction posed by Alan Hollinghurst, which I will repeat again: ‘masterly conformity in lifelong tension with the disruptive and innovatory force of his sexuality’. [21] I think, given Philpot’s sincere Catholicism we have to add this to the mix of explanation, its tendency to create almost blasphemous (from a very conventional perspective) mix of the queer, including relationships to outcasts working as models – white as well as black (witness the pictures from the 1920s below) which feature another favourite model, the “happy-go-lucky ne’er-do-well … affable layabout” George Bridgeman). In the pictures below Bridgeman appears as the Angel of the Annunciation. The picture places the viewer at the viewing point of the Virgin Mary, and hence we are not offered the lily of chastity.[22] That queerness was also possible to express by mixing the Classical (but definitively pagan) supernatural with Judaeo-Christian imagery is central to earlier Philpot, but contained perhaps too much of the elite distribution of classical education in the Britain at the time, which the updated imagery of the later paintings does not.

It is difficult not to recommend an exhibition I have myself not seen because of the quality of Simon Martin’s book and his deserved reputation for sensitive and educative queer curation. That I wish I could see it myself I have no doubt. I think that experience would just add to my appreciation of the artist and the curator who feature above. But, as it does to me, Chichester in a possible rail strike seems a long haul then do read this book. It is worthwhile and beautiful.

All the best

Steve

[1] Alan Hollinghurst (2022: 11f.) ‘Introduction’ in Simon Martin Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, 10 – 15.

[2] The phrase is that of J.G.P. Delaney in 2003 as cited by Simon Martin (2022: 111) Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, I extend its application from an analysis of psychosexual developments in Philpot’s life to include reference to other power dynamics in the relationships of human individuals and groups.

[3] Cited ibid: 161.

[4] See Simon Martin (2018: 40f) ‘Mediating Queerness: Recent Exhibitions at Pallant House’ in Jonathan Katz, Isabel Hufschmidt & Änne Söll (eds.) On Curating (Notes on Curating): Queer Curating Issue 37 (May 2018), 39 – 46.

[5] See Simon Martin’s ‘Preface’ for ‘critical race theory’ in Simon Martin (2022: 7) op.cit. 6 – 9.

[6] Hettie Judah (2022) ‘Glyn Philpot review – a master portraitist’s secret gay passion’ in The Guardian (Mon 16 May 2022 12.55 BST. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/16/glyn-philpot-review-pallant-house-chichester

[7] Nicola Coleby, Partnerships & Development Manager, and Jenny Lund, Curator of Fine Art at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove (2019) ‘Glyn Philpot: portraiture and desire’, Article for artuk.org (online) [25 Feb 2019] Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/glyn-philpot-portraiture-and-desire

[8] Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 194f.

[9] Discussed ibid: 152f. For text of essay (online) see Criteria of Negro Art — Red Wedge (redwedgemagazine.com)

[10] Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 51-53).

[11] Ibid: 158

[12] Patricia Lee Rubin (2018: 36 – 42) Seen From Behind: Perspectives on the Male body and Renaissance Art New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[13] Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 190f.).

[14] Alan Hollinghurst (2022: op. cit: 11f.)

[15] Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 146).

[16] Ibid: 145

[17] Robin Gibson (1985: 35) Glyn Philpot 1884 – 1937: Edwardian Aesthete to Thirties Modernism London, National Portrait Gallery.

[18] See photograph in Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 141)

[19] Robin Gibson op.cit: 31

[20] Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 141).

[21] Alan Hollinghurst (2022: op. cit: 11f.)

[22] Robin Gibson cited Simon Martin (2022 op. cit: 43).

2 thoughts on “Alan Hollinghurst says that the ‘cumulative impression’ he has taken from knowing the artist’s work is of Philpot’s ‘masterly conformity in lifelong tension with the disruptive and innovatory force of his sexuality’. This blog reflects on the 2022 book by Simon Martin, ‘Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit’”