From the very beginning Don Lamb, one of ‘a clerisy of bachelor dons’ seems to feel that the ‘span of time’ that is the summation of his life-story is both interpreted and sanctified by his being seen as the ‘embodiment of art history in Cambridge’: ‘The tautology of his name has always pleased him. Donnish, serious, dignified – that is how his life has been. … Sometimes the span of time seems like nothing. … His thoughts are the mirror image of Cambridge’s unchanging vistas, his mind sustained by the rituals of academic life’.[1] This blog reflects on the 2022 novel by James Cahill, ‘Tiepolo Blue’ (London, Sceptre) as a allegory of the ways in which the pursuit of sanctity in art and life is disrupted and aesthetic and moral models of ‘the orderly firmament’ are discovered to be illusions and myths attempting to hide the chaos of our actual unadorned lives.

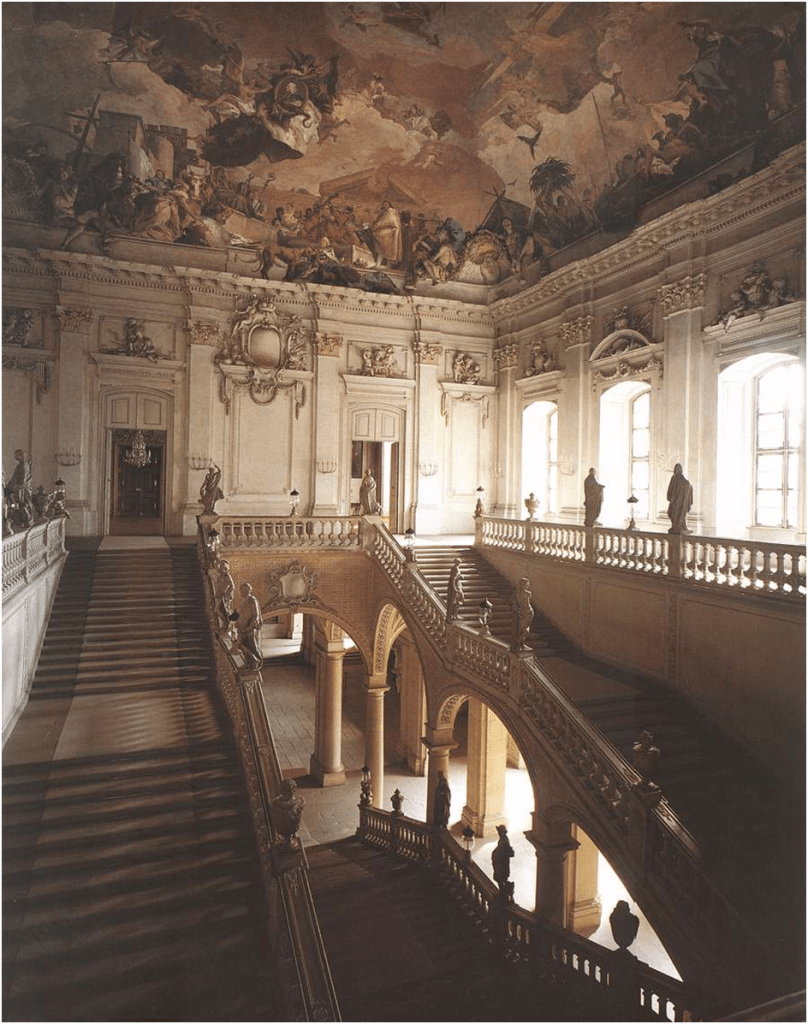

There is a religious slant to the language used to picture the academic life as represented by the ancient universities and their key disciplines; especially it would seem of the discipline of art history. It probably is the case that, even in the 1990s, when this novel is set, that art history never was much like the ways it is represented in Don Lamb’s version of it but the analogues are clear and are mentioned in the novel’s encyclopaedic take on the subject in the 1990s. Lamb sets the support of ‘classical forms’, or what his colleagues call the world of truth and beauty (emphasising I think the vagueness of these terms), over ‘Marxist credos’ and even the representation of likewise vague ideas of ‘sweetness and light’.[2] That final phrase, though used of the more undiscriminating appreciation of Tiepolo’s art, is of course the phrase used by Matthew Arnold in Culture and Anarchy to characterise how culture humanises and civilises the social world, particularly that culture represented by ancient universities, by bringing the best that has been ‘thought and said’ of the past into the concerns of the present and contemporary. I do not know if Cahill intended to reference Arnold here, but if he did, it would further define what Don Lamb means by ‘classical forms’, and distinguish his interest in them from what is human, social and therefore concerned with the dynamics of love and power in the relationships between sentient beings. For it is clear that Lamb’s view of art is a thing not concerned primarily with fleshly sentience and being touched by beauty whether in personal or in the fleshy elements of art but by ideas of proportion and measurement. Such an interest unites his interest in Palladio as an architect and his unlikely (in my view) thesis on Tiepolo as a painter and ornamental decorator in Don’s supposedly great but finally unwritten book . The latter characterisation is reductive of course although it is a justifiable reduction of how Tiepolo used trompe l’oeil deception and other techniques of theatrical illusion to turn the interior structure of buildings into what looks like, but is definitively NOT, a fleshed out and fantastically chaotic vision of the outer world tinged with extended allegoric reference, through fantastic embodiments, to the noumenal world, as posited by Kant.

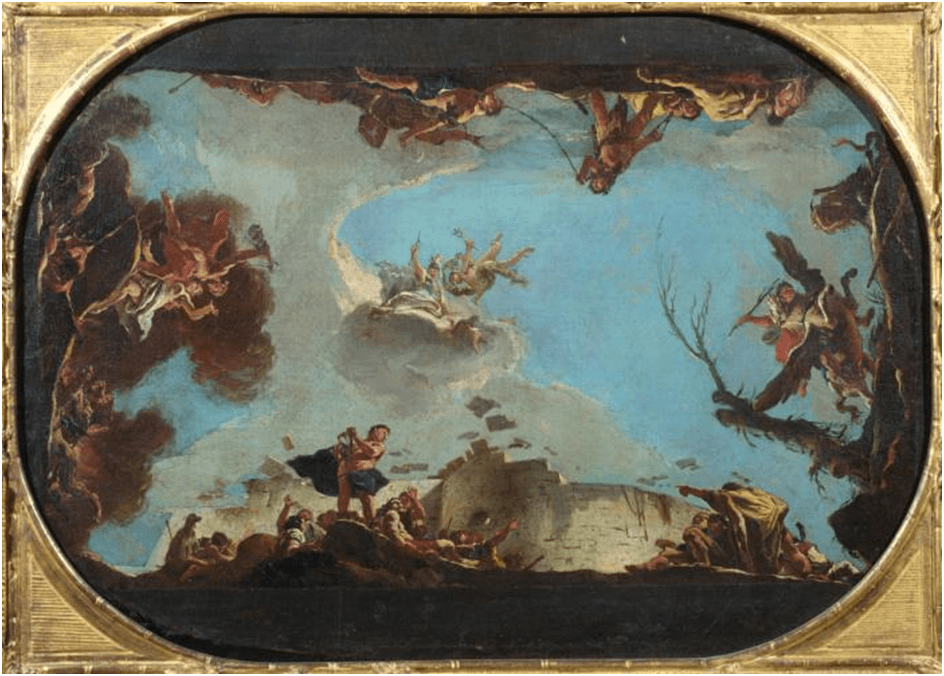

Take for instance the painting by Tiepolo that Don Lamb refers to in his Fitzwilliam Museum lecture early in Tiepolo Blue, the Allegory of the Power of Eloquence: ‘An image of shimmering sky flashes up behind him – the cosmos painted over the span of a ceiling, peopled by mythic characters, receding into a whirlpool of golden light’.[3] This sumptuous description of Tiepolo’s work contrast with the dryness of Lamb’s own work on these images, even in that very lecture which renders the fragility of the human efforts to comprehend a universe too large (and blue) for it in terms of ‘complex spatial hierarchies that underlie those apparently carefree scatterings of figures’:

He explains how each arrangement was exquisitely planned – mapped and measured according to the Golden Ratio – how every cloud and pocket of sky has its place in the classically proportioned system…[4]

This emphasis on the reduction of the ‘apparently carefree’ into hierarchy that is measurable and mapped is the ideal of Don’s donnishness and it is a long way from Matthew Arnold, let alone Marxist credos or any other application of human or socio-psychological theory to art. These absences are telling. Despite Lamb’s insistence that it’s ‘a little more complex than that’, the man who fascinates him with the thin by bizarrely crooked beauty of an appearance like that of Egon Schiele, calls him and his approach to art (having seen his amassed reproductions of Tiepolo covered with drawn perspective lines) that of a ‘measurer’.[5]

Even relatively early after the story shows Lamb’s disillusioned exit from Peterhouse College, Lamb himself is allowed a slight consciousness, eked from a third-person point of view narration style, that he: ‘needs to take some new approach. Is he right in everything he claims? Can the heavens really be measured like the portico of a building?’[6]

But the narrator does not see Tiepolo as Don does. Indeed Michael Donkor in his review of the novel in The Guardian says the narrative descriptions of Tiepolo’s ‘rich elaborateness’ have ‘a slightly melodramatic flavour’.[7] If so, and I find that an imprecise description to say the least, I would argue that this effect is to more to exaggerate the cognitive dissonance, at least on the subject of that great painter’s work, between the Don’s ‘donnish’ views and an attempt to grasp Tiepolo’s masked interest in a world lived on the edge of the senses. Despite the pretention of academia, and art history in particular in this novel, to claim that it can encompass the truth of what art has to offer, the limitations of both emerge from the abstruse and empty axioms academic characters in this novel use to summarise its perceptions. Indeed Lamb, for instance, loses his way when he tries to imagine, speaking apparently (but not really since we have already seen him rehearse his’ peregrination’, as he calls it) in a moment of off-script improvisation, of the meaning of art as a kind of ‘sanctity’. [8] He uses this phrase loosely here, as elsewhere when used to describe ‘the sanctity of the college’, where the word massively over-rates the significance of the life of celibate monasticism projected as the present reality of male lives in the oldest of the Cambridge colleges, Peterhouse, which is now feeling the ‘base’ presence of both contemporary art and female presence at the same time.[9]

Take the phrase on which Lamb’s Fitzwilliam lecture ends: ‘The flat adornment conceals an orderly firmament’. When he recalls that phrase he wonders if it is more than a ‘singsong refrain’ or like a nursery rhyme’.[10] For this phrase is empty of meaning, failing to describe either the effect of overlap between the use of more than two architectural dimensions as a painting ‘surface’ (in the junction of the vertical and horizontal interior surfaces or even the cornices that mediate them with which Tiepolo plays) in Tiepolo frescos or their illusory depth and resistance to containment in a frame.

If ‘flat adornment’ then is a poor description of Tiepolo’s situation-art, then so is, almost at the level of sublime obviousness the idea of an ‘orderly firmament’ to describe either Tiepolo’s skies – that variegated but omnipresent blue – or the idea of the cosmos contained therein. Just because Tiepolo sometimes confines figural dramas to the margins of his open heavens’ does not mean those dramas are not central to the content of the vision. Ben summarises this point to Don: ‘“the way you look at those pictures on your desk,” Ben says, “measuring the sky … You’re always looking away from the people. The actors, the story, the life …”’.[11]

And that is how Don looks at his own tidy life ‘from a disengaged angle’ before the advent into his life of the realities of his past and present attitudes to people, life and interactions.[12] Those realities include both suppressions and marginalisation of the need for either (or both) sex and relational power over others in self and others (and notably the ‘old poof’ Valentine Black, who has in every sense made him what he is) that will finally enable him to detect that both sex and power relations have been the ‘queer stuff’ of his base creation’ and will finally undo him as the characters of Valentine Black, Michael Ross and even Ben are seen to share real appreciation of how both sex and power coalesce to shape life outcomes to their final advantage, their own mortality allowing.[13]

That being said, those latter characters too use art history merely to adumbrate life in axioms. It is just that their axioms reveal their awareness of depths of feeling of which they are not in control, as Don feels he is. As a result of course they are able to control things more successfully than Don. They eventually win all the glittering prizes that accompany institutional life whilst Don fails in every test institutions set to eradicate mere humanity of response. Thus even though Don, in his new role as Director of the Brockwell collection in Dulwich, can call out his deputy, Michael Ross for his use of the ‘mantra of accessibility’ and ‘continental cant’ (meaning the art theory of Derrida) used in modern art curation, his own talk is merely a cover, the narrative reveals, for a man who spills red wine on a borrowed white suit and ‘floods the toilet in piss … in a wayward fashion, dancing off the floor and walls, flying in glittering arabesques’.[14] So much, the narrator shows, for Don’s rhetoric.

Valentine Black’s axiom for Tiepolo, and perhaps the Baroque and Rococo trends he and Don have made an academic living from, is no more sensible, But it is a phrase with much more resonance than that already discussed of Don’s, for it bows to the inner Dionysiac wildness of the refined art. Had Don been more knowing, he would have known this phrase as the proposal it was from Valentine to his beautiful and good-looking student:

“You’ll be seeing more of me, here and there. I lecture on neoclassical sculpture in the eighteenth century – the tranquil exterior, the baroque inner life – if that’s your kind of thing”.[15]

Three decades on Don remembers that phrase in a way that makes him aware that he is still wearing Val’s clothes, working in a job-role gifted to him by Val, and living in the ‘House Beautiful’ which he thinks belongs to Val. Yet he still has not seen the proposal for what it was – yet – just as (at the same point) he is not yet aware of the presence of his nemesis (Michael Ross) who will use his sexual allure (and ‘fine lips’) to take that house, job and ‘baroque inner life’ (covered by apparent tranquillity) from him.[16]

Language well used in this novel is often a cover or a ‘pose’ (Val’s book was called The Neoclassical Pose) for the selfish demand of sex and power rather than a vehicle of truth and beauty, as Don naively believes. This is a debate many people try to have with him, including the female artists who are the toys of male posturing and power-play in the novel, especially the constantly recalled Mariam Schwartz, seen only as the true owner of the House Beautiful and victim of Valentine Black’s sexualised power-play, once she comes out of the hiding the recesses of this novel’s spaces allow her. For instance in Peterhouse library the only reference to the latter’s art is ‘in an unlit corner where exhibition catalogues are held’ just as she has become a recluse, ‘exiled to a small ugly extremity of Mariam’s house (Beautiful) – Val’s doing no doubt – …’[17]

It is difficult to know how contemporary critical culture will evaluate this novel because it is so much about why that culture requires (as in Judy Cannon’s artwork – both artist and the work invented in words alone for the novel – SICK BED) that one, in Judy Cannon’s imagined comment, ‘question what you know, what you believe. To hell with dignifying life, art destabilises’.[18] Some reviewers will, of course, steer clear of saying that this novel has, or should have, any say on the nature of art, life and the interaction of the two. For Michael Delgado in the Literary Review believes it is, ‘despite the broader questions that rumble under the surface’, really a novel of vivid characters and in chief, a psychological exposé of its main character, Don Lamb being someone ‘not in control of his own life as we may have thought’.[19] I am not sure any reader might have seen this man as being in control from the start however, the beauty of the novel lies in the narrator’s cool exposition of the lack of actual control in academic lives, which believe themselves, contrary to all evidence, to be so. As a result this is a novel of absolutely wonderfully controlled ironic sentences which symbolise the uncertainty of that which declaims itself invulnerable. Take the first very beautiful paragraph.

It is late September – and a new term. Don Lamb has spent the afternoon in Jesus College library, reading letters from the eighteenth century. It has been raining – the air is still damp – but as he cycles back to Peterhouse, the sun comes out and catches the world off guard. The paths and trees of Christ’s Pieces look naked in its glare. …

In my view this is as perfect an opening as that of Austen’s Emma. But here it communicates the reclusiveness from the world of both Don as a character and his academic activity (an d that of others); especially their mutual backward looking attitude to time’s passage. It is this limited world – barely aware of the weather outside its cloisters that is said to caught ‘off guard’, to be exposed as ‘naked’ when, like the Emperor it thinks it wears new clothes. It is a moment of literary finesse – pointed to as a literary trope later in the novel by the absolutely delicious stereotypical but true Argentinean don, Ferdinand Fernando: ‘So riddled with contradictions! The naked man versus the imperial pose, the mortal body besides the emblems of status …’.[20] Fernando may be presented as a fool but this trope is, in a sense the story of both Don Lamb and the academic art history he represents: a flashily adorned man (think of Valentine Black’s many fabulous if outrageous suits worn by Don and later Michael Ross) reduced to the embarrassment of a naked, or part naked, man caught in sexual action (the key scene of which is that where children claim to watch him masturbating over nude gay porn on the internet)[21]. They are all dreadfully ‘mortal’ too in every sense, including in the hints of Val’s upcoming death. That this applies to all the male aspirants to academic power is semi-revealed to Don in a dream-like drug-induced possible hallucination in which he thinks he detects photographic evidence of both Ben and Michael Ross earning their succession to the power controlled by Valentine Black by mortally raw and fleshy naked sexual interactions with Valentine and each other.[22]

From the start then we are told that Don and the world he represents is repressed and guarded but, for that reason, vulnerable to surprises – any event it cannot expect and this cognitively control. See how beautifully that situation is modelled in this apparently artless paragraph detailing Don’s approach to the Fitzwilliam Museum to deliver his keynote lecture:

He shoulders off his overcoat and hands it to an attendant. The girl’s nervous smile makes him aware, for a moment, of his own simmering anticipation. Is it nervousness/ Dismissing the thought, he smiles back at here and prepares to scale the stairs. But just then, fingers close around his forearm. He turns.

That is quite a beautifully acute paragraph that not only questions how we anticipate immediate, and even not-so-immediate, futures but leaves the labelling of the sensation nakedly unnamed except as a symptom of our visceral response to surprise – mixed with threat and anticipated pleasure (which have similar psychosomatic appearance anyway in the viscera). That the fingers are not named when felt but only when interpreted after being seen is crucial – for it further plays with whether the girl is projecting her nervous apprehensions at dealing with Don or vice-versa. It is a perfect re-introduction to Valentine Black, who attempts to be in charge of how futures get written whether his own (in which the novel shows us he will fail) or other peoples. Delgado then, I think is surely wrong to believe that we ever thought of Don Lamb as ‘in control of his own life’. For we know from an early point of the novel that the future is difficult to read for an academic in art-history, when art and its adherents are changing, even if the entitled of academic learning is not. Don knows he acts and looks older than the actual age of his embodied self and dates his ‘point of origin’ as a man sadly not from his birth, access to an age of legal consent or schooling but from being presented with the fake scroll that represented his degree:

That was the beginning – and at forty-three he is still young, at least in academic terms. How strange that his mind should leap back now to that point of origin. He drifts in and out of consciousness, wondering if things were easier back then, when the future was pure potential.[23]

For whatever the future looks like to Lamb at any other point in the novel, it is not seen as something whose control is in his own hands. Michael Donkor in The Guardian is a much more sensitive reader of this prose, describing its effect (accurately in my view) as ‘delicious unease and pervasive threat’. But I like that he also sees why that prose is ‘delicious’ because he is aware that some of the best writing in this book is a very accurate capture of sex between men, saying: ‘In his writing about physicality and bodies combining ( ) he beautifully captures disorientation, tenderness and heat without tipping into excess’.[24]

The growing awareness of Don’s sexual powers explains why Valentine has always loved him not for his academic prowess as such but for his dunamis, which must Val says ‘be protected’ by getting Don out of the academic world.[25] This word dunamis, transliterated from the Greek by the text and possibly Val, is a complex one for though it represents the power of the Gods in a man has been adopted by Orthodox Christianity from the beginning (in the Greek New Testament for instance) to characterise Christ’s miraculous power or even to refer to miracles themselves.[26]

That power inhabits the writing about sex between men. Strangely enough Michael Delgado claims the descriptions of male sex would make ‘even [Alan] Hollinghurst blush a little’ (and I collude with this in the selectivity of the quotation below), although Donkor, again correctly in my view, sees the prose here capable (as elsewhere) of evoking ‘vertiginous, heightened emotion’. There are many examples I could cite but amongst the best must be Don’s awakening to the dunamis of perfectly sequenced mutuality in sex where surprise is absent because what shocks in the act is not a virtue of it being unexpected and unanticipated but of its mutually appealing satisfaction of desire.

He senses that he is not alone. … Don’s hand is suddenly in contact with a warm section of arm or calf. There is no noise, no movement. … Their two bodies are charged with a power which builds as they remain completely still. (my italics)[27]

And I think this is excellent because the evocation of the divine dunamis of the post-religious body is precisely that which the apparent monastic ‘sanctity’ of academic life in this novel (and art history – believe me it is true even of the Open University) lacks. Don is awakened by Ben’s body at one point, but at this juncture it still makes him run away from ‘the nearness of a man’s face – breathing, animate, almost touching his own’.[28] That word ‘touch’ is important because what the academic lacks, and not only in the arts, is a sense of the importance of being touched – of the realm of what is sensate and emotional as felt in the viscera and surface of the skin. This novel is the Bible of that return to sensation, for at root, even the calmest most elegant sentence of Jane Austen works on the senses to touch the mind too, and we can expect such intimacy to be entirely ‘clean’ in any sense of the word, for contact between bodies is also contact between layers of sweat and the embedded dust to which past lives have been reduced. It is how we find beauty in even images of waste and corruption as with this evocation of the sensations of Don touching both Ben and the lurid city by lounging ‘against the wall’ of a Soho pub:

Life seeps past in a warm, unclean flow – a noisy tide of shouting and laughter and car horns and distant music. It overlaps with Ben’s voice, like one current of water twining round another.

…/ …

At a certain point, memory itself bleeds out into the night, into the fetid drains of Old Compton Street.

Do read this novel. It is brilliant.

All the best

Steve

[1] James Cahill (2022) Tiepolo Blue London, Sceptre. The references cited are ibid: 27, 5, 9, & 5 respectively in order of appearance.

[2] Ibid: 6 & 9 respectively

[3] ibid: 12

[4] Ibid: 11

[5] Ibid; 126

[6] Ibid: 126

[7] Michael Donkor (2022: 68) ‘Lines of beauty: Review of Tiepolo Blue’ in The Guardian (Saturday 11/06/22) Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jun/11/tiepolo-blue-by-james-cahill-review-a-bold-debut-of-psychosexual-awakening

[8] Ibid: 12

[9] Ibid: 55

[10] Ibid: 13. Repeated in Lamb’s own memory, ibid: 35.

[11] Ibid: 178

[12] Ibid: 21

[13] Phrases from ibid: 121 & 55.

[14] Ibid: 222f.

[15] Ibid: 47

[16] See ibid: 129

[17] References to ibid: 23 & 337 respectively.

[18] Ibid: 30

[19] Michael Delgado (2020: 55) ‘Don’s Progress’ in the Literary Review (Issue 508 (June 2022)) Available in https://literaryreview.co.uk/dons-progress

[20] Cahill op.cit: 26

[21] Ibid: 300f.

[22] Ibid: 331f.

[23] Ibid: 36

[24] Michael Donkor op. cit.

[25] Cahill op.cit: 48

[26] See for examples Strong’s Greek: 1411. δύναμις (dunamis) — (miraculous) power, might, strength (biblehub.com)

[27] Cahill op.cit: 293

[28] Ibid: 155

3 thoughts on “‘The tautology of his name has always pleased him. Donnish, serious, dignified – that is how his life has been. … Sometimes the span of time seems like nothing. … His thoughts are the mirror image of Cambridge’s unchanging vistas, his mind sustained by the rituals of academic life’. This blog reflects on the 2022 novel by James Cahill, ‘Tiepolo Blue’ (London, Sceptre).”