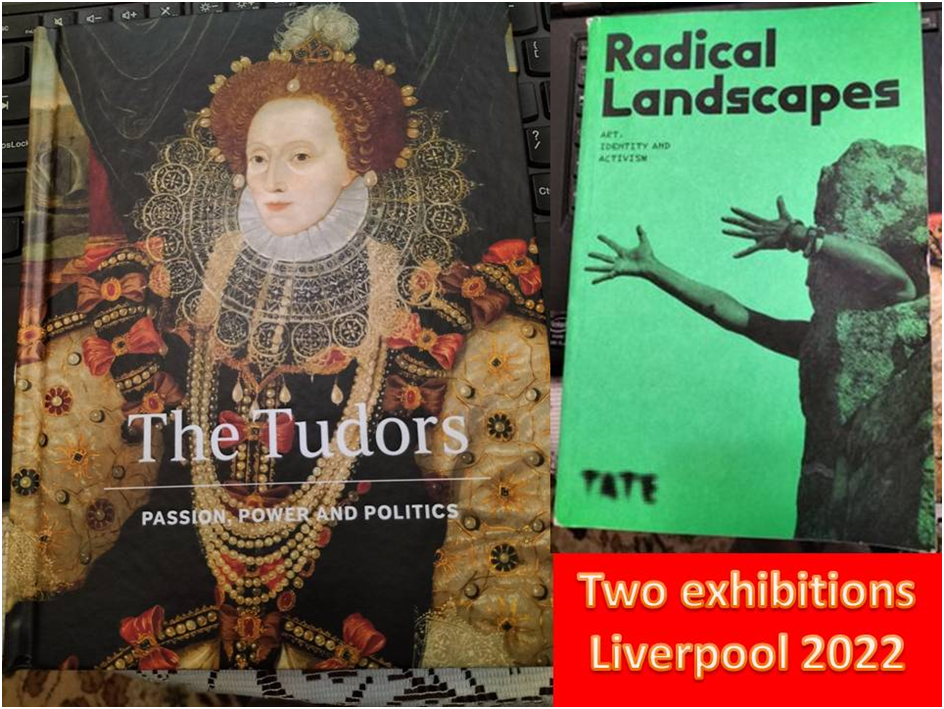

LIVERPOOL 2022 VISIT summary at end: ‘To be or not to be’! Let’s reflect on why some of us are not satisfied by art exhibitions that don’t convince us that they have one overarching, clear and coherent reason that justifies them making a show of themselves. This is a blog reflecting on how and why I was somewhat disappointed in two art exhibitions currently showing in Liverpool both containing some enormously significant individual works of art. These are The Tudors: Passion, Power and Politics, a National Portrait Gallery exhibition at the Walker Gallery and Radical Landscapes: Art, identity and Activism at Tate Liverpool.

Art exhibitions are always more than the items they contain, whether these items be works of art or exposés of information that fire a new interpretation of history or, as is often the case (and is an aim of both of these shows), interactions between both these kinds of item and others. Sometimes one emerges from an exhibition ‘buzzing’ from a particular work or series of linked works or a perception that seems new and makes you think again. Of all of these both of the exhibitions I saw were replete. Of these, in respect of the Tate’s Radical Landscapes exhibition at least, I have already picked up many in a previous blog discussing my expectations of that exhibition – available at this link. Of this exhibition I will say more but not based on any feeling of that my view of the works therein has been extended by the curation of the artworks into a whole experience that was evident in this exhibition.

I was very grateful to see artworks that have long been of importance of me. They are, after all, truly fine works. The Tudors exhibition offered, for instance, those tremendous ideological portraits of Elizabeth I such as the NPG’s version of the Armada Portrait and, of course, the hugely impressive (and well – just huge) Ditchley Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. Both stun with their colour and realisations of finesse of sartorial adornment and jewellery. Behind such show lies the sizable audacity of their allegory (as well as just literal size in the case of the Ditchley portrait) which edges onto the extremity of the hubris involved in use of art by the Tudors as a means of idealising total political control and domination by divinely-ordained (as they would have it) a monarch representing a whole people, nation and ‘Empire’.

An example of an ‘exposé( ) of information that fire(s) a new interpretation of history’ (again in regard to the Tudor exhibition) is worth examining since it stunned me in the exhibition. I would call the curation here brilliant because as the point is repeated at different points of the exhibition it at first illuminates an individual artwork before showing us that that very illumination calls for new historical research. This research is already in process. It is fired by the mere presence of John Blanke in The Westminster Tournament roll of 1511. In this art work John’s isolation as a sole representative of black people suggests, even if only implicitly, that the black population of Tudor England was largely unnoticeable: as a black person he is a solitary witness with ‘his existence made strange’ to the norms established in the piece. The follow up research (named the John Blanke Project) has shown however that his presence was not an anomaly in Tudor England.[1]

Thus these representations and facts excited, intrigued and stunned me. Another political insight into Tudor power as it touched upon queer history had the same effect, although I found this exposé clearer to grasp and reflect upon in the exhibition booklet than within the exhibition itself. It relates to a section expanded upon in the exhibition book by Kate O’Donoghue in a section named ‘Walter Hungerford and the 1533 Buggery Act’, which is, in the exhibition, a passing moment in items serving to illuminate the ways Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell persuaded English people to accept the dissolution of the monasteries they executed between 1536 and 1541.[2] The Act took away earlier exemptions from execution applied to monastic persons on proof of them taking part in the ‘detestable and abominable vice of buggery’, and was used as part of a campaign to represent the monasteries as rampant with vice, rather than the morality with which English people associated them. O’Donoghue cites a 1543 letter by Henry VIII stating that: ‘The extirpation of the monks and friars needs politic handling’.[3] The use of this tool politically to morally slur the Roman Catholic institutions is shown to by the Act’s repeal by Mary I and its reinstatement by sister Elizabeth. This was a tool then, as ‘queer sexual acts’ were to remain of exploiting and perhaps even creating a prejudice for larger political reasons of state. It appals but also interests.

But this use of interesting interpretations from less well-known historical facts exemplifies too the bitty nature, as I found it, of the exhibition as a whole. It featured great portraits but the connections between them were only those that illustrated the serial stories of a succession of monarchs, wives and lovers. Sometimes elements of beauty and interest, like Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas Wyatt below, are used to illustrate Elizabethan poetic arts. That example seemed to drop into the exhibition from nowhere and just to tire me of yet another idealised face, despite my love of Wyatt’s verse.

Reviewing the book for Radical Landscapes at the Tate I said:

‘In truth my expectation is that Laura Cummings’ (in a review in the Observer) ‘will be proved right about the show in two ways.

First that the show will prove ‘just a little too tame to be properly radical’. Second that it will be straining the point that she makes that it is of the nature of art proper and in itself, from Byzantium to David Hockney (but why stop there), ‘that makes the landscape seem strange’’.[4]

Both expectations were fulfilled and, indeed, I felt that the show was, apart from offering the joy of seeing in the original works by Paul Nash and Edward Burra (favourites of mine) very disappointing and poorly curated. No commonalities were highlighted and much straining was evident to find dubious commonality amongst the diverse themes and different political strategies employed in the artworks shown. One could not find a connection that excited.

A joy I did not expect however was seeing a work celebrating the transformation of the calendar year into made by the radical French Republican Calendar, wherein agricultural objects symbolise each day, in Ruth Ewan’s Back to the Fields. It fills an entire room with imagery from the landscape of a time where rural labour mattered for the many and could assert itself as independently meaningful against aristocratic classical posturing through symbols of time in older official formulations of the calendars. In memory it stays with me. That I failed to take steps to preserve the memory, I blame on the tedium of the curation (as I saw it) of this show generally. Again the bits were good (or some of them) but the whole failed to show curatorial intelligence or vim. This is even more the case given the minute font used on the captions for the works. It was as if carelessness about the viewer’s experience had been a studied effect.

Of the Liverpool experience itself I could not be happier. I loved and enjoyed enormously wandering around that strange mix of quarry remnant, necropolis and public rest place that is St. James Park.

And another glory was seeing the Lutyens crypt of the Catholic cathedral. Truly stunning. Truly so!

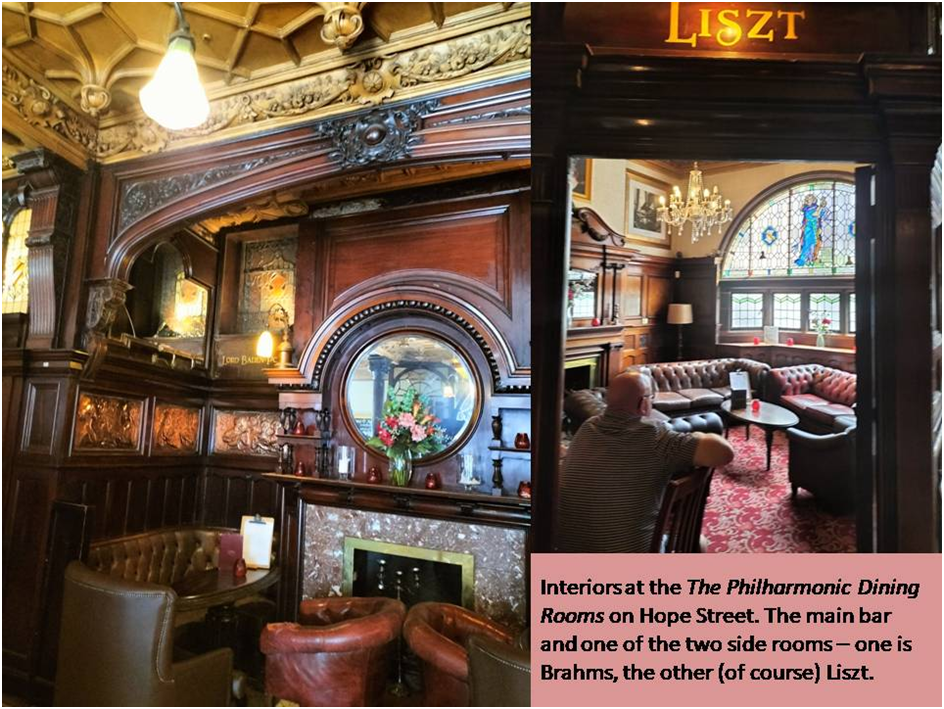

And of course Liverpool itself – a wondrous city. Even its pubs. Take the Philharmonic Dining Rooms on Hope Street, across the junction from the Liverpool Philharmonic’s home venue.

Liverpool CANNOT disappoint!

All the best

Steve

[1] page 30 in Michael I.Oharjuru (2022) ‘Insights into John Blanke’s Imagefrom the John Blanke Project’ in Charlotte Bolland (ed.) The Tudors: Passion, Power and Politics, London, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 28 – 31.

[2] In ibid: 48 – 51.

[3] Ibid: 48

[4] Laura Cumming (2022) Radical Landscapes review – consciousness-raising from the ground up [Sun 15 May 2022 13.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/15/radical-landscapes-tate-liverpoool-review

3 thoughts on “LIVERPOOL 2022 VISIT summary at end: ‘To be or not to be’! This is a blog reflecting on how and why I was somewhat disappointed in two art exhibitions currently showing in Liverpool both containing some enormously significant individual works of art. These are ‘The Tudors: Passion, Power and Politics’, a National Portrait Gallery exhibition at the Walker Gallery & ‘Radical Landscapes: Art, identity and Activism’ at Tate Liverpool.”